The Development and Impact of Formal Lang-Distance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology & Gaming

Technology & Gaming hub in the heart of the UK Fully serviced office space and facilities tailored to supporting business growth Welcome We are the premier location in the Midlands for technology and gaming businesses requiring flexible office space; from a fixed desk in our open plan facility to enclosed offices for up to 2,000 square feet. Forward House is located in Henley-in-Arden close to the M40 and a short walk from the train station, providing convenient access to Warwick, Birmingham, Oxford and surrounding areas. Forward House is a modern fully air-conditioned, grade ‘A’ office building with a grand marble floored entrance, providing serviced office space from one workstation upwards. As part of the benefits; rent, utility bills, air-conditioning, furniture, fit-out and cleaning are all part of the inclusive price you pay for serviced office space. Compared with conventional office space, the all-inclusive rate offers significant savings with additional services such as photocopying, centralised services, reception and admin support and postage available at value-for-money rates. Forward House Incubator offers high quality business accommodation, meeting & conference room facilities, training and interview rooms. All of the rooms are fitted with top quality furnishings that are attractive, professional, durable and comfortable, and are equipped with the latest audio visual equipment. In addition, there is ample kitchen space and breakout areas, free parking and access to centralised cost-effective services to meet your business requirements. In partnership with: mercia fund management “Forward House Workspace offers a superb place for people working in the games industry. Not only will they benefit from great office space and the ability to work alongside other games companies, but they have direct access to experts in finance, funding, business operations, marketing and gaming. -

Appendix Eight

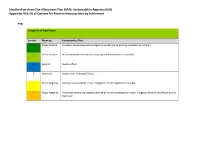

Stratford-on-Avon Site Allocations Plan (SAP): Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Appendix VIII: SA of Options for Reserve Housing Sites by Settlement Key: Categories of Significance Symbol Meaning Sustainability Effect ++ Major Positive Proposed development encouraged as would resolve existing sustainability problem + Minor Positive No sustainability constraints and proposed development acceptable 0 Neutral Neutral effect ? Uncertain Uncertain or Unknown Effects - Minor Negative Potential sustainability issues: mitigation and/or negotiation possible -- Major Negative Problematical and improbable because of known sustainability issues; mitigation likely to be difficult and/or expensive Alcester Settlement Baseline Overview relevant to SA objectives: SA Objective Settlement Assessment Heritage The historic market town of Alcester overlies the site of a significant Roman settlement on Icknield Street. The town was granted a Royal Charter to hold a weekly market in 1274 and prospered throughout the next centuries. In the 17th Century it became a centre of the needle industry. With its long narrow Burbage plots and tueries (interlinking passageways), the town centre street pattern of today and many of its buildings are medieval. There are a number of heritage assets which includes Scheduled Monuments, Listed Buildings, a Conservation Area and archaeological features within and adjacent to the urban area. The Conservation area’s character is defined by the medieval street pattern, the presence of a wide diversity of buildings with a range of distinguishing features, and the gaps between the buildings which create an intriguing spatial element. The majority of Alcester’s Listed Buildings are located within the Conservation Area, as are parts of the Alcester Roman Town Scheduled Monument.1 Landscape The Landscape Sensitivity Study identifies extensive areas of land adjacent to the town as being of high sensitivity to development. -

Public Rights of Way Guide Public Rights of Way

Public Rights of Way Guide Public Rights of Way Introduction Staffordshire has a network of over 4000 kilometres of public footpaths and bridleways, which offer the single most important means of exploring every corner of the County. Whether you wish to explore Staffordshire by foot, cycle or on horseback, we hope that the information contained in these pages will help you and provide you with some ideas about the opportunities available to you. There are many opportunities for walking and riding in Staffordshire from long distance recreational routes such as the Staffordshire Way and the Way for the Millennium, the Heart of England Way and the Sabrina Way. There are many shorter, Country Trails and Promoted Routes, several of which are based around County Council Country Parks, Picnic Areas and Greenways. All of these are promoted by the County Council and are waymarked. Before starting off, you may wish to check whether there are any disruptions to the path network in your chosen area by checking if there are any Temporary Closures or Proposed Diversions. We are continually working, with Parish Councils, voluntary groups and local organisations, through the County Council's Community Paths Initiative to promote and develop such routes for your enjoyment. Generally speaking, the responsibility for keeping public paths open for public use is shared by the County Council, as highway authority, and landowners. The County Council is responsible for the surface maintenance of the paths and for dealing with unlawful obstructions. Landowners are responsible for keeping the paths free from obstruction. The County Council also ensures that all routes are legally protected on the definitive map. -

SICCA LODGE A4 8Pp.Indd

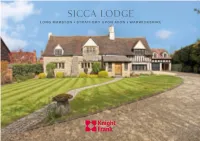

Sicca Lodge LONG MARSTON STRATFORD UPON AVON WARWICKSHIRE Sicca Lodge WYRE LANE LONG MARSTON STRATFORD UPON AVON WARWICKSHIRE A beautiful Grade ll listed period detached village residence of architectural and historical interest with ancillary accommodation believed to have 15th century origins. Accommodation & Amenities Entrance hall Dining room Sitting room Drawing room Kitchen/diner Utility room Conservatory Master bedroom Two further double bedrooms Single bedroom Two bathrooms Double garage with ancillary accommodation above Carport Workshop Gardens Stratford upon Avon 5 miles, Welford on Avon 1 mile, Chipping Campden 6miles M40 (J15) 15 miles, Birmingham 23 miles. (Distances approximate) Knight Frank LLP Bridgeway House, Bridgeway, Stratford upon Avon CV37 6YX Tel: +44 1789 297 735 [email protected] www.knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Situation • Long Marston is an attractive village to the south of Stratford upon Avon and to the northern edge of the Cotswolds. There are many interesting period houses and cottages, a lively pub, village shop with post office and a very early parish church. It is reputed that King Charles II stayed here in disguise escaping from the Parliamentarians after the Battle of Worcester in September 1561 • There is direct access to the Greenway cycle path, which takes you to Stratford upon Avon and Meon Vale and which forms part of the Monarch’s Way and crosses the Heart of England Way • Chipping Campden and Stratford upon Avon are almost equidistant and both offer facilities for day to day requirements. -

From £350,000

Plot 2, Albany, Wixford, Alcester, B49 6DA From £350,000 A small development built by established developers Templeoak, comprising of five properties, one four bedroom detached and four semi-detached properties lying on the edge of the small village of Wixford. Plot 2 comprises of hall, downstairs cloakroom, separate sitting room, breakfast/family area leading off to a separate utility, master bedroom en-suite, three further bedrooms, family bathroom, single garage and gardens. WIXFORD Wixford is a village in Warwickshire, UK, one and magnificent brass of Thomas de Crewe dating from 1411, and GROUND FLOOR CLOAKROOM with sanitary ware from a half miles south of Alcester. Its church, dedicated to Saint a 17th century priest's stable in the graveyard. Moor Hall dates Roper & Rose comprising low level, wash hand basin. Milburga of Wenlock, was founded in the 12th century. For from the 15th century. much of the late 19th and early 20th century people travelled SITTING ROOM 14' 4" x 10' 10" (4.37m x 3.3m) with from Alcester to the Sunday evening services in St Milburga's. A small development built by established developers Templeoak, window to front, wall mounted electric fire point. comprising of five properties, one four bedroom detached and Both the Heart of England Way (popular with hikers) and the four semi-detached properties lying on the edge of the small KITCHEN/DINING/FAMILY ROOM 20' 6" x 17' 10" River Arrow run through the village. Tired walkers can enjoy a village of Wixford. Plot 2 is a semi-detached house which has (6.25m x 5.44m) fitted with a Sheraton kitchen with quartz work drink and food in the two village pubs, The Fish Inn or The Three under floor heating to all tiled areas and has solar panel for hot tops and up stand splash back, Bosch integrated appliances Horse Shoes. -

Warwickshire, Coventry and Solihull Sub- Regional Green Infrastructure Study

Warwickshire, Coventry and Solihull Sub - Regional Green Infrastructure Study Prepared for Natural England by Land Use Consultants July 2011 www.landuse.co.uk LUC SERVICES Environmental Planning Landscape Design Landscape Management Masterplanning Landscape Planning Ecology Environmental Assessment Rural Futures Digital Design Urban Regeneration Urban Design 43 Chalton Street 37 Otago Street London NW1 1JD Glasgow G12 8JJ Tel: 020 7383 5784 Tel: 0141 334 9595 Fax: 020 7383 4798 Fax: 0141 334 7789 [email protected] [email protected] 14 Great George Street 28 Stafford Street Bristol BS1 5RH Edinburgh EH3 7BD Tel: 0117 929 1997 Tel: 0131 202 1616 Fax: 0117 929 1998 [email protected] [email protected] DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET Version Status: Version Details: Prepared Checked Approved by: by: by: Ver: Date: Principal 1 09/05/11 Draft Final Report Louise Philip Philip Smith Tricklebank Smith 2 13/0 7/11 Final Report Louise Philip Philip Smith Tricklebank Smith 3 27/07/11 Final Report (reissue with Stratford Louise Philip Philip Smith changes) Tricklebank Smith CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 2 2 DEFINING AND IDENTIFYING SUB-REGIONAL ASSETS 3 Defining Sub-Regional Green Infrastructure Assets ................................................... 3 Identifying Sub-Regional Assets ............................................................................... 4 3 ANALYSIS OF GI SUPPLY AND FUNCTIONAL NEED 10 Analysis by Local Authority .................................................................................. 11 North Warwickshire Borough -

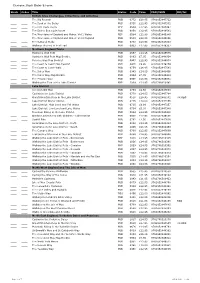

Cicerone Stock Order & Form

Cicerone Stock Order & Form Stock Order Title Status Code Price EAN/ISBN UK/Int British Isles Challenges, Collections and Activities ____ ____ The Big Rounds PUB 0772 £18.95 9781852847722 ____ ____ The Book of the Bothy PUB 0756 £12.95 9781852847562 ____ ____ The C2C Cycle Route REP 0649 £12.95 9781852846497 ____ ____ The End to End Cycle Route PUB 0858 £12.95 9781852848583 ____ ____ The Mountains of England and Wales: Vol 1 Wales REP 0594 £12.99 9781852845940 ____ ____ The Mountains of England and Wales: Vol 2 England PUB 0589 £12.99 9781852845896 ____ ____ The National Trails PUB 0788 £18.95 9781852847883 ____ ____ Walking The End to End Trail PUB 0933 £17.95 9781852849337 Northern England Trails ____ ____ Hadrian's Wall Path PUB 0557 £14.95 9781852845575 ____ ____ Hadrian's Wall Path Map Booklet PUB 0893 £7.95 9781852848934 ____ ____ Pennine Way Map Booklet PUB 0907 £12.95 9781852849078 ____ ____ The Coast to Coast Map Booklet PUB 0926 £9.95 9781852849269 ____ ____ The Coast to Coast Walk PUB 0759 £16.95 9781852847593 ____ ____ The Dales Way PUB 0943 £14.95 9781852849436 ____ ____ The Dales Way Map Booklet PUB 0944 £7.95 9781852849443 ____ ____ The Pennine Way PUB 0906 £16.95 9781852849061 ____ ____ Walking the Tour of the Lake District NYP 1049 £14.95 9781786310491 Lake District ____ ____ Coniston Old Man PUB 0763 £2.50 9781852847630 ____ ____ Cycling in the Lake District PUB 0778 £14.95 9781852847784 ____ ____ Great Mountain Days in the Lake District PUB 0516 £18.95 9781852845162 UK REG ____ ____ Lake District Winter Climbs PUB 0716 -

Shugborough Hall and Sherbroo

Shugborough Hall and Sherbrook Valley Circular Walk This lovely walk begins along the Trent and Mersey Canal where it is possible to see a wide variety of wildlife, in particular Kingfishers if you are lucky. The walk then enters the magnificent Shugborough estate, before reaching The Satnall Hills and Milford Common, popular walking destinations, and returning to Seven Springs via the Stepping Stones. Distance: Approx. 12.8km (8 miles) Duration: 4 hours Terrain: Easy paths with slight hills at Milford Common and in the Sherbrook Valley Parking: Seven Springs car park near Weetmans Bridge on theA513. Refreshments: Toilets and Refreshments are available in Milford, which is just a short detour from the main walk Map: OS Explorer 244 “Cannock Chase” Bus Route: Route between Stafford, Milford and Lichfield. Route of Service 825 Shugborough Hall 1 Walk back down the drive of Seven Springs car park until you reach the A513. Cross this road to the small lane directly opposite, before crossing the iron bridge over the River Trent. 2 Continue along this road heading up towards Little Haywood, passing beneath the railway. As you get to the canal bridge, turn right down onto the canal. On reaching the towpath double back under the bridge. You are now on the Staffordshire Way. 3 As you walk along the canal there are views of the Shugborough Estate to the left. Turn left off the towpath just before reaching bridge no. 73 and cross through a metal Essex Bridge gate. Turn left and cross the Essex Bridge, the longest packhorse bridge in England. -

Moor House - Upper Teesdale B6278 Widdybank Farm, Langdon Beck, River Tees NNR Forest-In-Teesdale, B6277 Barnard Castle, Moor House – Cow Green Middleton- Co

To Alston For further information A686 about the Reserve contact: A689 The Senior Reserve Manager Moor House - Upper Teesdale B6278 Widdybank Farm, Langdon Beck, River Tees NNR Forest-in-Teesdale, B6277 Barnard Castle, Moor House – Cow Green Middleton- Co. Durham DL12 0HQ. Reservoir in-Teesdale To Penrith Tel 01833 622374 Upper Teesdale Appleby-in- National Nature Reserve Westmorland B6276 0 5km B6260 Brough To Barnard Castle B6259 A66 A685 c Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Kirkby Stephen Natural England 100046223 2009 How to get there Front cover photograph: Cauldron Snout The Reserve is situated in the heart of © Natural England / Anne Harbron the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is in two parts on either Natural England is here to conserve and side of Cow Green Reservoir. enhance the natural environment, for its intrinsic value, the wellbeing and A limited bus service stops at Bowlees, enjoyment of people and the economic High Force and Cow Green on request. prosperity that it brings. There is no bus service to the Cumbria © Natural England 2009 side of the Reserve. ISBN 978-1-84754-115-1 Catalogue Code: NE146 For information on public transport www.naturalengland.org.uk phone the local Tourist Information Natural England publications are available Centres as accessible pdfs from: www.naturalengland.org.uk/publications Middleton-in-Teesdale: 01833 641001 Should an alternative format of this publication be required, please contact Alston: 01434 382244 our enquiries line for more information: 0845 600 3078 or email Appleby: 017683 51177 [email protected] Alston Road Garage [01833 640213] or Printed on Defra Silk comprising 75% Travel line [0870 6082608] can also help. -

Route Map for Basingstoke Community Transport Service 55A (Outbound)

Jazz 1 Chineham Town Centre Brighton Hill Hatch Warren Kempshott Park from 14 April 2013 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS except Public Holidays low floor easyaccess Mattock Way Thumwood 0624 0644 0702 0712 0722 0732 0742 0754 0806 0818 0833 0848 00 12 24 36 48 1400 1412 1424 Chineham Village Hall 0630 0650 0709 0719 0729 0739 0749 0801 0813 0825 0840 0855 07 19 31 43 55 1407 1419 1431 Chineham Centre Tesco 0726 0736 0746 0756 0808 0820 0832 0847 0901 13 25 37 49 01 1413 1425 1437 Daneshill Roundabout 0637S 0659S 0718S 0732 0742 0752 0802 0814 0826 0838 0853 0906 18 30 42 54 06 1418 1430 1442 Basingstoke Bus Station (arr stand G) 0645 0708 0727 0737 0747 0757 0807 0819 0831 0843 0858 0910 22 34 46 58 10 1422 1434 1446 minutes at Basingstoke Bus Station (dep stand G) 0532 0557 0622 0647 0659 0709 0719 0729 0739 0749 0759 0809 0823 0835 0847 0902 0914 26 38 50 02 14 1426 1438 1450 12 Cobbett Green 0539 0604 0629 0655 0707 0717 0727 0737 0747 0757 0807 0817 0831 0843 0855 0910 0922 34 46 58 10 22 until 1434 1448 1500 Brighton Hill Asda 0542 0607 0632 0658 0710 0720 0730 0740 0750 0800 0810 0820 0837 0849 0901 0913 0925 37 49 01 13 25 1437 1452 1504 Danebury Road The Crofts d d d d d d d d d d d d 0844 0856 0908 0920 0932 44 56 08 20 32 1444 1500 1512 Hatch Warren Sainsburys 0849 0901 0913 0925 0937 49 01 13 25 37 1449 1506 1518 Kempshott Park Wedderburn Avenue 0548 0613 0638 0705 0717 0729 0739 0749 0759 0809 0819 0829 0853 0905 0917 0929 0941 then every 53 05 17 29 41 1453 1510 1522 Hatch Warren Sainsburys 0556 0621 0646 0713 0725 0737 0747 0757 0807 -

A Long Walk to Berwick

A long walk to Berwick The Great Outdoors magazine, November 2016 I’d been a long time getting to Berwick: you could reckon it in hours, years or decades, depending where you started from. Hours: eight. That wasn’t bad for 23 miles from Wooler. Years: ten, since I’d set out from Land’s End with a vague plan, to walk 800 miles across England, a bit at a time. Decades: six and a bit. I never before had found the excuse to walk through Berwick-upon-Tweed, though I’d shot past it on the train often enough, and it seemed a nice sort of place to go to, with its border history, estuary location and recently-ended war with Russia. The vagueness of my plan to cross England was very much the point. That unholy trinity of work, family and finance meant that opportunities to get into the great outdoors from my London home were all too limited, essentially just one short break a year, everything else just local lowland walking. I’d got frustrated with cherry-picking different bits of the nation each year – the North Devon Coast one time, the Black Mountains another, say. I was the sort of guy who needed a plan, one that involved a nice B&B at the end of the day. I didn’t do spartan. And that plan, before England, was Wales, starting 2002. I’d walked Offa’s Dyke Path a few years before, and it came to me that finding and walking a different, wilder, hillier line across that grand little nation might be fun. -

THE SCENIC HIGHLIGHTS of the PENNINE WAY Discover the True Spirit of the North on England’S Original National Trail

ENGLAND’S GREAT WALKING TRAILS | THE PENNINE WAY LIMESTONE AND LEGEND: THE SCENIC HIGHLIGHTS OF THE PENNINE WAY Discover the true spirit of the North on England’s original National Trail Steeped in history and traversing spectacular upland landscapes in some of England’s most popular National ParKs, the Pennine Way is the most iconic of England’s Great WalKing Trails. Stretching for 268 miles (435Km) across England’s wild northern uplands, with a combined ascent that eXceeds the height of Mount Everest, it’s also arguably the toughest. OVERVIEW • Distance: 74 miles/120km • Start/Finish: Skipton/Appleby-in-Westmorland • Number of Days: 8 • Grade: Challenging • Theme: History / Geology • Landscape: Type High Hills & Moorland Opened in 1965, the Pennine Way blazed a trail for public access to some of England’s wildest landscapes – hitherto the sole preserve of a wealthy elite. Conceived by founder member of The Ramblers Tom Stephenson and popularised by the legendary Alfred Wainwright, the full route follows the rocky spine of England – stretching from the hills of the Derbyshire Peak District, through the Yorkshire Dales and onwards through Durham and Northumberland to the Scottish Border. Roughly following the line of the watershed from which great rivers like the Tyne and the Tees, the Lune and the Eden, flow east and west respectively, the bulk of this legendary trail lies at more than 1,000ft/305m above sea level. Our shortened 8-day itinerary explores the striking limestone landscapes of Malham in the Yorkshire Dales before climbing up onto the lonely massif of Cross Fell, where the Lakeland Fells are clearly visible across the Eden Valley.