Text and Talk Professional Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anders Nyström, Katatonia, on „The Fall of Hearts“

Anders Nyström, Katatonia, on „The Fall of Hearts“, new band-members and touring plans »It’s a play between light and dark, if you don’t have the light, you won’t see the dark« Prior to the release of the tenth Katatonia album The Fall of Hearts on the 20th of May, I had the chance to speak to guitar player Anders Nyström about the recordings and the songwriting of the album, new band members and touring plans of the swedish kings of dark melancholic progressive metal. Zur deutschen Übersetzung des Interviews Anders, the upcoming Katatonia album „The Fall of Hearts“ will mark the first ‘fully distorted’ release since 2012’s highly acclaimed „Dead End Kings“ (excluding the live release „Last Fair Day Gone Night“, 2014). Having worked on the ‘metal-less’ 2013 re-imagining of Dead End Kings entitled Dethroned„ & Uncrowned“ (2013) and extensive subsequent acoustic tours culminating in the Live DVD release of „Sanctitude“ last year, how much has this rather long absence from fully plugged heaviness influenced the songwriting for The Fall of Hearts? I think, by doing the many „Dethroned & Uncrowned“ and „Sanctitude“ acoustic gigs and album we opened up a new door for our audience to choose, to get familiar with, to accept a new sound of Katatonia. We never tried to claim or anything that this was the indication of our new style. It was just a little side experiment to show that we have more sides than just one in Katatonia. We also could show a softer more lushy acoustic side that would still sound like Katatonia. -

Reference Document Including the Annual Financial Report

REFERENCE DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2012 PROFILE LAGARDÈRE, A WORLD-CLASS PURE-PLAY MEDIA GROUP LED BY ARNAUD LAGARDÈRE, OPERATES IN AROUND 30 COUNTRIES AND IS STRUCTURED AROUND FOUR DISTINCT, COMPLEMENTARY DIVISIONS: • Lagardère Publishing: Book and e-Publishing; • Lagardère Active: Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage; • Lagardère Services: Travel Retail and Distribution; • Lagardère Unlimited: Sport Industry and Entertainment. EXE LOGO L'Identité / Le Logo Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins Echelle: d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. Agence d'architecture intérieure LAGARDERE - Concept C5 - O’CLOCK Optimisation Les entrepreneurs devront s’engager à executer les travaux selon les règles de l’art et dans le respect des règlementations en vigueur. Ce 15, rue Colbert 78000 Versailles Date : 13 01 2010 dessin est la propriété de : VERSIONS - 15, rue Colbert - 78000 Versailles. Ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation. tél : 01 30 97 03 03 fax : 01 30 97 03 00 e.mail : [email protected] PANTONE 382C PANTONE PANTONE 382C PANTONE Informer, Rassurer, Partager PROCESS BLACK C PROCESS BLACK C Les cotes indiquées sont données à titre indicatif et devront être vérifiées par les entrepreneurs. Ceux-ci devront soumettre leurs dessins d’éxécution pour approbation avant réalisation. L’étude technique des travaux concernant les éléments porteurs concourant la stabilité ou la Echelle: Agence d'architecture intérieure solidité du bâtiment et tous autres éléments qui leur sont intégrés ou forment corps avec eux, devra être vérifié par un bureau d’étude qualifié. -

Low-Volume Roads Subscriber Categories Chairman

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD No. 1426 Highway and Facility Design; Bridges, Other Structures, and Hydraulics and Hydrology Lo-w-Volutne Roads: Environtnental Planning and Assesstnent, Modern Titnber Bridges, and Other Issues A peer-reviewed publication of the Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL NATI ONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. 1993 Transportation Research Record 1426 Sponsorship of Transportation Research Record 1426 ISSN 0361-1981 ISBN 0-309-05573-3 GROUP 5-INTERGROUP RESOURCES AND ISSUES Price: $25. 00 Chairman: Patricia F. Waller, University of Michigan Committee on Low-Volume Roads Subscriber Categories Chairman:. Ronald W. Eck, West Virginia University IIA highway and facility design Abdullah Al-Mogbel, Gerald T. Coghlan, Santiago Corra UC bridges, other structures, and hydraulics and hydrology Caballero, Asif Faiz, Gerald E. Fisher, Richard B. Geiger, Jacob Greenstein, George M. Hammitt II, Henry Hide, Stuart W. TRB Publications Staff Hudson, Kay H. Hymas, Lynne H. Irwin, Thomas E. Mulinazzi, Director of Reports and Editorial Services: Nancy A. Ackerman Andrzej S. Nowak, Neville A. Parker, James B. Pickett, George B. Associate Editor/Supervisor: Luanne Crayton Pilkington II, James L. Pline, Jean Reichert, Richard Robinson, Associate Editors: Naomi Kassabian, Alison G. Tobias Bob L. Smith, Walter J. Tennant, Jr., Alex T. Visser, Michael C. Assistant Editors: Susan E. G. Brown, Norman Solomon Wagner Office Manager: Phyllis D. Barber Senior Production Assistant: Betty L. Hawkins G. P .. Jayaprakash, Transportation Research Board staff The organizational units, officers, and members are as of December 31, 1992. Printed in the United States of America Transportation Research Record 1426 Contents Foreword v Part 1-Environmental Planning and Assessment Environmental Impact Assessment and Evaluation of Low-Volume 3 Roads in Finland Anders H. -

Katatonia and Ulsect to Inferno Metal Festival 2018

KATATONIA AND ULSECT TO INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2018 Doom metal-kongene fra Sverige, KATATONIA, og Nederlands kommende tekniske death metal-stjerner, ULSECT, er bekreftet til den 18. utgaven av Inferno Metal Festival! INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2018: EMPEROR – OBITUARY – IHSAHN – CARPATHIAN FOREST - DARK FUNERAL – KATATONIA – NAPALM DEATH – FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE – TSJUDER – MEMORIAM – ORIGIN – ONE TAIL, ONE HEAD – NECROPHOBIC – KRAKOW – ODIUM – NORDJEVEL – AUÐN – DJEVEL – MEPHORASH – AHAB – EARTH ELECTRIC- VANHELGD – UADA – WIEGEDOOD – ERIMHA – ULSECT KATATONIA Svenske Katatonia ble dannet i 1991 og ble raskt kjent for sin unike miks av gothic doom og death metal. Sammen med britiske band som Paradise Lost og My Dying Bride ble Katatonia definerende for sjangeren. På senere album fikk Katatonia et mer rocka og melodiøst sound, noe man tydelig kan høre på bandets tredje skive «Discouraged Ones». I 2016 kom Katatonias ellevte studioalbum ut under tittelen «The Fall of Hearts». Bandet har siden da turnert Sør-Amerika, Europa, Australia og Nord-Amerika med stor suksess. Dette blir Katatonia sitt første besøk på Inferno Metal Festival og det loves en opplevelse av de sjeldne. https://www.facebook.com/katatonia/ ULSECT Ulsect er Season of Mists nyeste band på labelen og bandet har nettopp sluppet sitt debutalbum. Ulsect kommer fra den nederlandske byen Tilburg – som fra før er kjent for black metal-bandet Dodecahedron og prog-bandet Textures. Ulsect kommer fra dette miljøet og har med seg gitarist Joris Bonis og trommeslager Jasper Barendregt fra Dodecahedron, samt tidligere Textures-bassist Dennis Aarts. Det kommer derfor ikke som en overraskelse at elementer fra disse bandene gjennomsyrer Ulsects fantastiske debutalbum. Skiva låter som en frekk blanding av pionerer som Gorguts og Deathspell Omega. -

Progressive Metal Monterrey, Mx

PROGRESSIVE METAL MONTERREY, MX Booking & Management: [email protected] PROGRESSIVE METAL MONTERREY, MX Status: Active Formation: 2008 Lyrics: Afterlife, Cosmic Horror, Duality, Entropy, Creation, Evolution /theadventequation BIOGRAPHY Officially active band since 2008, resulting in an EP named “Sounds From Within” on the same year, recorded in their hometown, Monterrey Mexico. First Full Length Album “Limitless Life Reflections” released through Concreto Records (Independent Label) with national distribution and great public reception; giving the band the opportunity to play in important events and festivals around Mexico. Participating as opening acts for, Haggard, Opeth, Tesseract, Dark Tranquility Second Full Length Album “Remnants Of Oblivion” released digitally on December 2020 and physically by Mexico’s Label Concreto Records accompanied by a solid return plan to social media and current streaming platforms. Album reception with very positive reviews from critics, nominated album of the week in several countries in LATAM as well as referred to as extraordinarily executed within Progressive & Technical Metal zines and nominated to best release of 2020 within Mexico & different other countries CARLOS LICEA ROBERTO CHARLES LUIS GOMEZ MARGIL H. VALLEJO Piano & Keyboards Drums & Percussion Guitars Bass & Vocals Click to Listen to Each Album DISCOGRAPHY LIMITLESS LIFE REFLECTIONS Full Length Album – 2012 A 60-minute juggernaut of power and beauty. Produced, engineered & mixed by Charles A. Leal at Psicofonia Studio, with Studio Mastering by Jens Bogren (Opeth, Katatonia, Amon Amarth, Devin Townsend) at Fascination Street studios, Örebro, Sweden, and general Artwork by Colin Marks ( Scar Symmetry, Whitechapel, Suffocation) at Rain Song Design, London, England. REMNANTS OF OBLIVION NEW FULL LENGTH ALBUM – December 4th, 2020 A duality between heaviness & melody that translates into a complete musical & emotional experience. -

Encuentro Internacional Sobre La Historia Del Seguro

Instituto de Ciencias del Seguro Encuentro Internacional sobre la Historia del Seguro © FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra sin el permiso escrito del autor o de FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE no se hace responsable del contenido de esta obra, ni el hecho de publicarla implica conformidad o identificación con la opinión de los autores. Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra sin el permiso escrito del autor o del editor. © 2010, FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE Paseo de Recoletos 23 28004 Madrid (España) www.fundacionmapfre.com/cienciasdelseguro [email protected] ISBN: 978-84-9844-210-6 Depósito Legal: SE-6825-2010 © FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra sin el permiso escrito del autor o de FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE PRESENTACIÓN En el marco de los actos conmemorativos del 75 Aniversario de MAPFRE tuvo lugar en Madrid, los días 8 y 9 de mayo de 2008, el Encuentro Internacional sobre la Historia del Seguro en el que, con la participación de prestigiosos especialistas, se analizó la Historia del Seguro en Reino Unido, Alemania, Francia, Italia, España y Suecia, así como en Estados Unidos, Japón y los países de América Latina. La idea de convocar este Encuentro Internacional surgió durante el proceso de elaboración del libro De Mutua a Multinacional. MAPFRE 1933 / 2008, por los historiadores Gabriel Tortella, Leonardo Caruana y José Luis García Ruiz. La organización del Encuentro Internacional estuvo a cargo de Andrés Jiménez, Presidente de MAPFRE RE y de la Comisión del 75 Aniversario de MAPFRE, y del profesor Leonardo Caruana. -

John-Murray-Translation-Rights-List

RIGHTS TEAM John Murray Press Rebecca Folland Rights Director - HHJQ Translation Rights List - Autumn 2019 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3122 6288 NON-FICTION General Non-Fiction 7 Joanna Kaliszewska Head of Rights - John Murray Press Current Affairs, History & Politics 8 Deputy Rights Director - HHJQ [email protected] Popular Science 18 +44 (0) 20 3122 6927 Popular/Commercial Non-Fiction 25 Hannah Geranio Senior Rights Executive - HHJQ Travel 27 [email protected] Recent Highlights 31 FICTION Nick Ash Literary Fiction Rights Assistant - HHJQ 37 [email protected] General Fiction 47 Crime & Thriller 48 Hena Bryan Rights Assistant - JMP & H&S Recent Highlights 52 [email protected] JOHN MURRAY PRESS For nearly a quarter of a millennium, John Murray has been unashamedly populist, publishing the absorbing, SUBAGENTS provocative, commercial and exciting. Albania, Bulgaria & Macedonia Anthea Agency [email protected] Seven generations of John Murrays fostered genius and found readers in vast numbers, until in 2002 the firm be- Brazil Riff Agency [email protected] came a division of Hachette, under the umbrella of Hodder & Stoughton. China and Taiwan Peony Literary Agency marysia@peonyliterary agency.com IMPRINTS Czech Republic & Slovakia Kristin Olson Agency [email protected] At John Murray, we only publish books that take us by sur- prise. Classic authors of today who were mavericks of their Greece OA Literary Agency time – Austen, Darwin, Byron – were first published and [email protected] championed by John Murray. And that sensibility continues today. Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia Katai and Bolza Literary Agency [email protected] (Hungary) Two Roads publish about 15 books a year, voice-driven [email protected] (Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia) fiction and non-fiction – all great stories told with heart and intelligence. -

NEW RELEASE GUIDE March 19 March 26 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 12 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 19

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE March 19 March 26 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 12 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 19 2021 ISSUE 7 March 19 ORDERS DUE FEBRUARY 12 NEW EP ELASTICITY FROM SERJ TANKIAN TRACKLISTING 1. ELASTICITY 2. YOUR MOM 3. HOW MANY TIMES? 4. RUMI 5.ELECTRIC YEREVAN • New EP “ELASTICITY” from Serj Tankian (System Of A Down) out on 3/19/21. UPC: 4050538653694 Returnable: Yes CAT: 538653692 Explicit: Yes • First Instant Grat track “ELASTICITY” out Box Lot: 30 CD File Under: Rock SRP: $9.98 on 2/5/21 together with a video and EP Packaging: Digipack Release Date: 3/19/21 4 050538 653694 pre-order. • “ELECTRIC YEREVAN” will be the focus track and comes out alongside the EP on 3/19/21. It’s will also be featured in a trailer and end credits for the upcoming Serj Tankian directed documentary TRUTH IS POWER out on 4/27/21. Artist: Saxon Release date: 19th March 2021 Title: Inspirations Territory: World Ex. Japan Genre: Metal FORMAT 1: CD Album (Digipack) Cat no: SLM106P01 / UPC: 190296800504 SPR: $13.99 - 3% Discount applicable till Street Date FORMAT 2: Vinyl Album Cat no: SLM106P42 / UPC: 190296800481 SPR: $34.98 SAXON PROUDLY DISPLAY THEIR “INSPIRATIONS” WITH NEW CLASSIC COVERS RELEASE British Heavy Metal legends Saxon will deliver a full-roar-fun-down set of covers on March 19th 2021 (Silver Lining Music), with their latest album Inspirations, which drops a brand new 11 track release featuring some of the superb classic rock songs that influenced Biff Byford & the band. From the crunching take on The Rolling Stones’ ‘Paint It Black’ and the super-charged melodic romp of The Beatles’ ‘Paperback Writer’ to their freeway mad take on Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Stone Free’, Saxon show their love and appreciation with a series of faithful, raw and ready tributes. -

Fiches Thématiques Europresse

REGARDS ANGLOPHONES SUIVEZ CETTE ACTUALITÉ AVEC : • The Independent (Grande Bretagne) RESTEZ INFORMÉ • The Financial Times (Grande AVEC EUROPRESSE ! Bretagne) • The Trade (Royaume-Uni) • The Daily Star (Liban) • Daily Tribune (Bahreïn - site web réf.) Consultez toutes les • Gulf News (Emirats Arabes Unis – site sources pour les web) bibliothèques • The Observer (Australie) publiques et de • The Chronicle ( Australie) l’enseignement sur • Xinhua – News Agency (China) www.europresse.com. • The Korea Times (Corée du Sud) • The New-York Times (Etats-Unis) • Indian Currents (Inde) • Japon Economic Foundation (Japon) … Et bien d’autres titres ! L’ACTUALITÉ ÉCONOMIQUE ET POLITIQUE FRANÇAISE SUIVEZ CETTE ACTUALITÉ AVEC : • Le Monde RESTEZ INFORMÉ • Le Figaro AVEC EUROPRESSE ! • Libération • Les Echos • L’Obs • La Tribune Consultez toutes les • La Croix sources pour les • L’Humanité bibliothèques • L’Express publiques et de • Le Point l’enseignement sur • Challenges www.europresse.com. • Le Parisien Economie • Bulletin Quotidien • Les Dossiers de l’actualité • Valeurs actuelles … Et bien d’autres titres ! REGARDS FRANCOPHONES SUIVEZ CETTE ACTUALITÉ AVEC : RESTEZ INFORMÉ • Le Temps (Suisse) AVEC EUROPRESSE ! • La Tribune de Genève (Suisse) • Le Soir (Belgique) • La Libre Belgique (Belgique) • L’Orient – Le Jour (Liban) Consultez toutes les • El Watan (Algérie) sources pour les • La Tribune Afrique (Maroc) bibliothèques • Le Matin (Maroc – site web réf) publiques et de • Le Temps Tunis (Tunisie) l’enseignement sur • Le Devoir (Canada) www.europresse.com. • L'Actualité (Canada) …. Et bien d’autres titres ! PRESSE GRAND PUBLIC SUIVEZ CETTE ACTUALITÉ AVEC : • L’Équipe RESTEZ INFORMÉ • Télérama AVEC EUROPRESSE ! • Science et Avenir • TéléObs • Auto Moto Consultez toutes les • Marie France sources pour les • Maison Côté Ouest bibliothèques • Historia publiques et de • Le Nouveau Magazine Littéraire l’enseignement sur • Maison et Travaux www.europresse.com. -

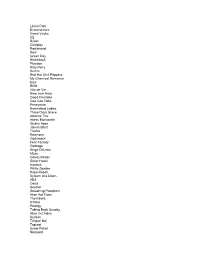

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

Copyrighted Material

Contents Notes on Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Part I Formal Fallacies 35 Propositional Logic 37 1 Affirming a Disjunct 39 Jason Iuliano 2 Affirming the Consequent 42 Brett Gaul 3 Denying the Antecedent 46 Brett Gaul Categorical Logic 49 4 Exclusive Premises 51 Charlene Elsby 5 Four Terms 55 Charlene Elsby 6 Illicit Major and Minor Terms 60 Charlene Elsby 7 Undistributed Middle 63 CharleneCOPYRIGHTED Elsby MATERIAL Part II Informal Fallacies 67 Fallacies of Relevance 69 8 Ad Hominem: Bias 71 George Wrisley 0003392582.INDD 5 7/26/2018 9:46:56 AM vi Contents 9 Ad Hominem: Circumstantial 77 George Wrisley 10 Ad Hominem: Direct 83 George Wrisley 11 Ad Hominem: Tu Quoque 88 George Wrisley 12 Adverse Consequences 94 David Vander Laan 13 Appeal to Emotion: Force or Fear 98 George Wrisley 14 Appeal to Emotion: Pity 102 George Wrisley 15 Appeal to Ignorance 106 Benjamin W. McCraw 16 Appeal to the People 112 Benjamin W. McCraw 17 Appeal to Personal Incredulity 115 Tuomas W. Manninen 18 Appeal to Ridicule 118 Gregory L. Bock 19 Appeal to Tradition 121 Nicolas Michaud 20 Argument from Fallacy 125 Christian Cotton 21 Availability Error 128 David Kyle Johnson 22 Base Rate 133 Tuomas W. Manninen 23 Burden of Proof 137 Andrew Russo 24 Countless Counterfeits 140 David Kyle Johnson 25 Diminished Responsibility 145 Tuomas W. Manninen 0003392582.INDD 6 7/26/2018 9:46:56 AM Contents vii 26 Essentializing 149 Jack Bowen 27 Galileo Gambit 152 David Kyle Johnson 28 Gambler’s Fallacy 157 Grant Sterling 29 Genetic Fallacy 160 Frank Scalambrino 30 Historian’s Fallacy 163 Heather Rivera 31 Homunculus 165 Kimberly Baltzer‐Jaray 32 Inappropriate Appeal to Authority 168 Nicolas Michaud 33 Irrelevant Conclusion 172 Steven Barbone 34 Kettle Logic 174 Andy Wible 35 Line Drawing 177 Alexander E. -

Analyzing Meaning an Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics

Analyzing meaning An introduction to semantics and pragmatics Paul R. Kroeger language Textbooks in Language Sciences 5 science press Textbooks in Language Sciences Editors: Stefan Müller, Martin Haspelmath Editorial Board: Claude Hagège, Marianne Mithun, Anatol Stefanowitsch, Foong Ha Yap In this series: 1. Müller, Stefan. Grammatical theory: From transformational grammar to constraint-based approaches. 2. Schäfer, Roland. Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen. 3. Freitas, Maria João & Ana Lúcia Santos (eds.). Aquisição de língua materna e não materna: Questões gerais e dados do português. 4. Roussarie, Laurent. Sémantique formelle : Introduction à la grammaire de Montague. 5. Kroeger, Paul. Analyzing meaning: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics. ISSN: 2364-6209 Analyzing meaning An introduction to semantics and pragmatics Paul R. Kroeger language science press Paul R. Kroeger. 2018. Analyzing meaning: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics (Textbooks in Language Sciences 5). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/144 © 2018, Paul R. Kroeger Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-034-7 (Digital) 978-3-96110-035-4 (Hardcover) 978-3-96110-067-5 (Softcover) ISSN: 2364-6209 DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1164112 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/144 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=144 Cover and concept of design: