All Materials Recycling Study: Total Solid Waste Prepared for the DELAWARE SOLID WASTE AUTHORITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PWTB 200-1-137 Concrete Recycling Alternatives for Military Installations

PUBLIC WORKS TECHNICAL BULLETIN 200-1-137 15 DECEMBER 2014 CONCRETE RECYCLING ALTERNATIVES FOR MILITARY INSTALLATIONS Public Works Technical Bulletins are published by the US Army Corps of Engineers, Washington, DC. They are intended to provide information on specific topics in areas of Facilities Engi- neering and Public Works. They are not intended to establish new Department of Army policy. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY US Army Corps of Engineers 441 G Street NW Washington, DC 20314-1000 CECW-CE Public Works Technical Bulletin 15 December 2014 No. 200-1-137 FACILITIES ENGINEERING ENVIRONMENTAL CONCRETE RECYCLING ALTERNATIVES FOR MILITARY INSTALLATIONS 1. Purpose a. This Public Works Technical Bulleting (PWTB) provides guidance for the use of recycled concrete at Army installations in the continental United States (CONUS). b. All PWTBs are available electronically at the National Institute of Building Sciences’ Whole Building Design Guide webpage, which is accessible through this link: http://www.wbdg.org/ccb/browse_cat.php?o=31&c=215 2. Applicability This PWTB applies to all US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Districts and Department of the Army CONUS installation personnel that are responsible for generating or managing concrete materials from construction projects, or those who specify, purchase, and utilize aggregate products. 3. References a. Army Regulation (AR) 200-1, "Environmental Protection and Enhancement," Chapter 10, “Waste Management,” Section 2, “Solid waste,” 13 December 2007. b. AR 420-1, “Army Facilities Management,” 12 February 2008. 1 15 December 2014 PWTB 200-1-137 c. Memorandum, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Installation Management (OACSIM), "Sustainable Management of Waste in Military Construction, Renovation and Demolition Activities" February 2006, revised 11 July 2006. -

Waste Cement and Concrete Management As Cost- Effective and Environment Friendly: Principles and Perspectives

CD08-002 WASTE CEMENT AND CONCRETE MANAGEMENT AS COST- EFFECTIVE AND ENVIRONMENT FRIENDLY: PRINCIPLES AND PERSPECTIVES I.M. Kelayeh1, A.A. Mounesan2, K. Siamardi3, M.M. Khodavirdi Zanjani3 1 Member of Management Association, Assistant of Technology & Development, Civil 2Civil Engineer, Sharif University of Technology, General Manager of Atisaz Company 3Civil Engineer, Concrete Research Center, Atisaz Company ABSTRACT The use of recycled aggregates in concrete opens a whole new range of possibilities in the reuse of materials in the building industry. The utilization of recycled aggregates is a good solution to the problem of an excess of waste material, provided that the desired final product quality is reached. The studies on the use of recycled aggregates have been going on for 50 years. In fact, none of the results showed that recycled aggregates are unsuitable for structural use. Using the recycled aggregate is a cost-affective and environmental friendly solution which is required general waste concrete management knowledge. This paper is focusing on waste cement and concrete management for optimizing the construction costs. The ways for reducing the green house gases (GHG) at cement and batch plants are suggested. A comparison among Iran industrial utilized cement volume and other countries was performed. Finally, it can be concluded that application of recycling concrete could reduce the costs by reducing truck traffic, providing the Non- Renewable Resource, Better Trucking Utilization (Reduced Costs), Allow down to 10% Deleterious Materials in Iran. Keywords: waste concrete management, utilized cement volume, cement plants, concrete recycling, GHG reduction. 1. INTRODUCTION The amount of construction and demolition waste (CDW) has increased considerably over the last few years. -

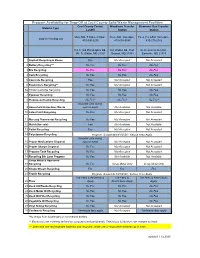

Program Availability for Drop-Off at Cecil County Solid Waste

Program Availability for Drop-Off at Cecil County Solid Waste Management Facilities Cecil County Central Woodlawn Transfer Stemmers Run Transfer Material Type Landfill Station Station Mon.-Sat. 7:30am-3:30pm, Tues.-Sat. 8am-4pm, Tues.,Fri.,&Sat. 8am-4pm, www.ccrecycling.org 410-996-6275 410-658-6646 410-275-2142 758 E. Old Philadelphia Rd., 565 Waibel Rd., Port 45 Stemmers Run Rd., (Rt. 7), Elkton, MD 21921 Deposit, MD 21904 Earleville, MD 21919 1 Asphalt Recycling & Reuse Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 2 Battery Recycling*** No Fee No Fee No Fee 3 Bra Recycling No Fee No Fee No Fee 4 Cork Recycling No Fee No Fee No Fee 5 Concrete Recycling Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 6 Electronics Recycling** No Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 6a Printer Cartridge Recycling No Fee No Fee No Fee 7 Eyewear Recycling No Fee No Fee No Fee 8 Fluorescent Lamp Recycling No Fee* No Fee* No Fee* Available only during 9 Household Hazardous Waste special event Not Available Not Available 10 Latex Paint Recycling No Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 11 Mercury Thermostat Recycling No Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 12 Mulch (for sale) Fee Not Available Not Available 13 Pallet Recycling Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 14 Polystyrene Recycling Program Suspended 8/1/2020 - Refuse Fees Apply Available only during 15 Proper Medications Disposal special event Not Accepted Not Accepted 16 Proper Sharps Disposal No Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 17 Propane Tank Recycling No Fee Not Accepted Not Accepted 18 Recycling Bin Loan Program No Fee Not Available Not Available Scrap Metal -

The Cement Sustainability Initiative

The Cement Sustainability Initiative Recycling Concrete Executive summary World Business Council for Sustainable Development Introduction Concrete is everywhere. It is the second most consumed material after water Recycling concrete and it shapes our built environment. Homes, schools, hospitals, offices, roads reduces natural and footpaths all make use of concrete. Concrete is an excellent material to make long-lasting and energy-efficient buildings. However, even with resource exploitation good design, human needs change and potential waste will be generated. and associated Changes in infrastructure planning and needs result in the generation of transportation costs, construction and demolition waste (C&DW): an estimated 900 million and reduces waste tonnes every year in Europe, the US and Japan. going to landfill. The Cement Sustainability Initiative (CSI) has been looking at the recycling However, it has little of concrete as a component of better business practice for sustainable impact on reducing development. Concrete has fairly unique properties and its recovery often greenhouse gas falls between standard definitions of reuse and recycling. Concrete is broken emissions. down into aggregate for use in a new life. This new life is usually road works aggregates, but in some areas it is also used as aggregates in new concrete. In some countries near full recovery of concrete is achieved. However, in Twice as much many parts of the world the potential to recover concrete is overlooked concrete is used in and it ends up as unnecessary waste in landfill. Furthermore, concrete construction around waste statistics are generally difficult to secure. This is partially explained by the world than the the relatively low hazard that the waste poses compared with some other materials, resulting in low public concern. -

Concrete Pavement Recycling

Concrete Pavement Recycling Mark B. Snyder, Ph.D., P.E. Pavement Engineering and Research Consultants (PERC), LLC Engineering Consultant to CP Tech Center What is Concrete Recycling? • Breaking, removing and crushing hardened concrete from an acceptable source. • Old concrete pavements often are excellent sources of material for producing RCA. • Concrete pavements are 100% recyclable! 2 In-Place Concrete Recycling • When RCA is to be used in a subbase layer of the roadway and/or shoulders, production can be accomplished using an in-place concrete recycling train. 3 Recycling Ready-Mixed Concrete • Approximately 5% of the 445 million cubic yards of ready mixed concrete produced in the U.S. each year is returned to the concrete plant. • Recycling this material, as with recycling any existing concrete material, presents significant sustainable benefits, including reduction of landfill use and virgin aggregate use. 4 Reasons for Concrete Recycling • Dwindling landfill space/increasing disposal costs – 50000 U.S. landfills accepting PCC in 1980 – 5000 U.S. landfills accepting PCC in 2000 • Rapidly increasing demand for aggregates with limited resources • Sustainability – Conservation of materials – Potential reduced environmental impact due to reduced construction traffic, reduced landfill – Cost savings • Potential for improved pavement performance • A proven technology – it works! 5 Potential Pavement Performance Improvements • Foundation stability; angular, rough texture and secondary cementing action. • Concrete strength; partial substitution of RCA for virgin fine aggregate may increase concrete compressive strength. 6 Concrete Recycling: A Proven Technology! 41 of 50 states allow use of RCA in various applications (FHWA, 2004) 7 Uses of Recycled Concrete Aggregate • PCC pavement – Single and Two-Lift • HMA pavement • Subbase – Unbound – Stabilized • Fill material • Filter material • Drainage layer 8 Unstabilized Subbases/Backfill • Most common application for RCA in U.S. -

Environmental Impact of Concrete Recycling, Coming from Construction and Demolition Waste (C&Dw)

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF CONCRETE RECYCLING, COMING FROM CONSTRUCTION AND DEMOLITION WASTE (C&DW) Authors: Beatriz Estévez*a , Antonio Aguadoa, Alejandro Josaa a Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya (UPC), School of Civil Engineering (ETSECCPB), Jordi Girona 1-3, Módulo C1, E-08034 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT This paper presents the results of a research study on the environmental impact produced by the recycling of concrete originating from construction and demolition waste (C&DW). The aim of the study was to implement a life cycle inventory (LCI) of the concrete recycling phases. It was carried out in Spain, with data collected from the various recycling processes involved in the mobile crushing plants operating in Catalonia. The values have been compared with the environmental impact produced during the extraction processes of natural resources (gravel and sand) from different European databases. The main emissions (CO2, NOx, SO2, SOx, and dust) with major influence on the greenhouse effect, acidification, and eutrophication were considered. The recycling waste processes generate lower environmental impact than the natural aggregate extraction. The amount of CO2 emitted is approximately 3,000 g per ton of recycled aggregate, while this value varied from around 6,900 to 7,700 g per ton for the gravel and sand extraction processes considered. INTRODUCTION In the EU, the current annual production of construction and demolition waste (C&DW) is on the order of about 180 million tonnes, of which, about 28% is recycled (EU, 1999). Several countries have implemented Action Programmes to increment the amount of recycled material. (Lauritzen, 1997). These countries included Spain, where 25 to 30 % of C&DW was being recycled by the year 2000, and where the Environment Ministry has proposed an Action Programme (BOE, 2001) to increase these values, so as to recycle at least 40% by 2005, and 60% by the year 2006. -

PWTB 200-1-27 Reuse of Concrete Materials from Building Demolition

PUBLIC WORKS TECHNICAL BULLETIN 200-1-27 14 SEPTEMBER 2004 REUSE OF CONCRETE MATERIALS FROM BUILDING DEMOLITION Public Works Technical Bulletins are published by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Washington, DC. They are intended to provide information on specific topics in areas of Facilities Engineering and Public Works. They are not intended to establish new DA policy. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 441 G Street, NW Washington, DC 20314-1000 CEMP-CE Public Works Technical Bulletin 14 September 2004 No. 200-1-27 FACILITIES ENGINEERING ENVIRONMENTAL REUSE OF CONCRETE MATERIALS FROM BUILDING DEMOLITION 1. Purpose. The purpose of this Public Works Technical Bulletin (PWTB) is to transmit information on the state of practice for recycling/reuse of concrete materials from building demolition. 2. Applicability. This PWTB applies to all U.S. Army facilities engineering activities. 3. References. a. Army Regulation (AR) 200-1, Environmental Protection and Enhancement, 21 February 1997. b. Army Regulation (AR) 420-49, Utility Services, 28 April 1997. c. Army TM 5-822-10/AFM 88-6, “Standard Practice for Pavement Recycling” (26 August 1988). 4. Discussion. a. Army Regulation (AR) 200-1, para. 5-10 contains policy for solid waste management, including participation in recycling programs and the sale of recyclables. b. AR 420-49 contains policy and criteria for the operation, maintenance, repair, and construction of facilities and systems, for efficient and economical solid (nonhazardous) waste PWTB 200-1-27 14 September 2004 management including source reduction, re-use, recycling, collection, transport, storage, and treatment of solid waste. -

Environmental Assessment of Two Use Cycles of Recycled Aggregate Concrete

sustainability Article Environmental Assessment of Two Use Cycles of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Tereza Pavl ˚u 1,* , Vladimír Koˇcí 2 and Petr Hájek 1 1 University Centre for Energy Efficient Buildings, Technical University, Prague, Trinecka 1024, 273 43 Bustehrad, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Department of Environmental Chemistry, Faculty of Environmental Technology, University of Chemistry and Technology, Technicka 5, 166 28 Praha 6—Dejvice, Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-724-507-838 Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 1 November 2019; Published: 5 November 2019 Abstract: The main goal of this study was to compare two use cycles of natural aggregate concrete and recycled aggregate concrete, which is another way to compare the environmental impacts of recycled materials. A series of concrete mixtures with various replacement ratios of primary resources with recycled ones were prepared for this study. The mechanical properties of concrete mixtures were examined and were used for the design of structural elements in the same utilized properties. The two use cycles of a structural element were compared using life cycle assessment (LCA). In the first use cycle, the LCA of the structural element containing only primary raw materials was assessed. In the second use cycle, the LCA of a structural element in which primary materials were partially replaced by recycled ones was assessed. The obtained results confirm the potential use of high-quality recycled aggregate originating from local sources in some applications in building structures. Furthermore, the environmental assessment indicates the benefits of using recycled materials, such as environmental savings, especially the reduction of primary resource use, embodied energy, and embodied emissions, as well as reduction of the pressure on landfill sites. -

Economic Comparison of Concrete Recycling: a Case Study Approach

Economic comparison of concrete recycling: a case study approach Author Tam, Vivian Published 2008 Journal Title Resources, Conservation and Recycling DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2007.12.001 Copyright Statement © 2008 Elsevier. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/24107 Link to published version http://www.elsevier.com/locate/resconrec Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Economic Comparison of Concrete Recycling: A Case Study Approach Vivian W. Y. Tam1* Abstract Recycling of construction material helps saving the limited landfill space. Among various types of materials, concrete waste accounts for about 50% of the total waste generation. The current practice for dumping construction materials to landfills generates a significant quantity of waste from construction sites. Recycling concrete waste as recycled aggregate is one of the methods to reduce the concrete waste. Therefore, this paper investigates the economical considerations in recycling concrete waste. A comparative study on costs and benefits between the current practice and the concrete recycling method is examined. The study shows that it has a negative net benefit for the current practice while a positive net benefit for the concrete recycling method. Therefore, recycling concrete as aggregate for new concrete production can provide a cost-effective method for the construction industry and help saving the environment. Keywords: Benefit, cost, economical, recycling, concrete, construction 1 Introduction The promotion of environmental management and the mission of sustainable development worldwide have exerted the pressure for the adoption of proper methods to protect the environment across all industries including building and construction. -

Recycling Concrete Pavements EB043P

ENGINEERING BULLETIN EB043P Recycling Concrete Pavements Recycling Concrete Pavements This publication is intended SOLELY for use by PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL who are competent to evaluate the significance and limitations of the information provided herein, and who will accept total responsibility for the application of this information. The American Concrete Pavement Asso- ciation DISCLAIMS any and all RESPONSIBILITY and LIABILITY for the accuracy of and the application of the information contained in this publication to the full extent permitted by law. PAVEMENT ASSOCIATION AMERICAN CONCRETE American Concrete Pavement Association 5420 Old Orchard Rd., Suite A100 Skokie, IL 60077-1059 www.pavement.com AMERICAN CONCRETE EB043P EB043P AMERICAN CONCRETE PAVEMENT ASSOCIATION PAVEMENT ASSOCIATION Recycling Concrete Pavements American Concrete Pavement Association 5420 Old Orchard Rd., Suite A100 Skokie, IL 60077-1059 (847) 966-ACPA www.pavement.com ACPA is the premier national association representing concrete pavement contractors, cement companies, equipment and materials manufacturers and suppliers. We are organized to address common needs, solve other problems, and accomplish goals related to research, promotion, and advancing best practices for design and construction of concrete pavements. Recycling Concrete Pavements Keywords: AASHTO, ASTM, aggregate, alkali-aggregate reactivity (AAR), alkali-carbonate reactivity (ACR), alkali-silica reactivity (ASR), asphalt-treated subbase (ATB), base, beneficiation, carbonation, cement-treated subbase -

Recycled Concrete

RECYCLED CONCRETE INTEGRATED PAVING SOLUTIONS The Construction Materials Recycling Association estimates that about WHAT IS IT? 140 million tons of concrete are recycled each year in the U.S. alone. Typically, recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) is used as granular fi ll, Eventually, all pavements must base and sub-base material, or as aggregate in new concrete pavement. be replaced. After a long and Why do it? reliable service life, concrete Reusing concrete pavement minimizes the amount of raw materials required pavements can be crushed and for a new pavement structure. With aggregates comprising between 70% to 85% by mass of the concrete mixture, it makes sense both economically and reused. In fact, concrete is 100% environmentally to reuse the existing pavement. recyclable (and the steel rebar Producing recycled concrete aggregates is simple and economical. While RCA within is recyclable as well). can be transported virtually anywhere, reusing the concrete at its original site (in-place recycling) has several benefi ts that can save on costs. By eliminating the costs of removing old concrete, factoring in savings on disposal costs, and the potential cost of road damage from transport of virgin or waste materials, some states have estimated savings of up to 50% to 60% from using recycled aggregates versus buying new aggregate. In-place concrete recycling reduces construction costs because a contractor doesn’t have to locate a recycling center or pay for hauling the materials away. This ultimately saves money for taxpayers and agencies. Environmental benefi ts of in-place recycling include reduced truck traffi c, reduced fuel consumption and improved air quality by limiting exhaust fumes. -

Concrete Recycling and Disposal Fact Sheet Publication WA 605 Rev

Concrete Recycling and Disposal Fact Sheet Publication WA 605 Rev. 2017 P.O. Box 7921 Madison, Wisconsin 53707-7921 What is the purpose of this fact sheet? concrete is latex or oil-based and if it has been coated with lead-bearing paint. The responsible This fact sheet is intended to help property owners, individuals include: renovation and demolition contractors and used concrete handlers determine what painted concrete The property owner can be recycled or how it must be disposed of. Individuals carrying out a renovation or demolition “Clean” concrete is exempt by rule from most project regulations. With certain location limitations, clean Individuals that later take ownership or control of concrete may be crushed and used as fill, aggregate painted concrete materials for recycling or in road beds or concrete to concrete recycling. Most disposal painted concrete can be used for these purposes in accordance with rule exemptions. This fact sheet So, tell me again, exactly what painted concrete explains when painted concrete is considered clean should have the paint tested for lead? and is exempt for use vs. when painted concrete is Paint on concrete should be tested for lead if the not considered clean and where a specific approval paint is not latex-based and both of the following are is required by the Department of Natural Resources. true: 1. The painted concrete will be processed and/or On what basis is painted concrete considered used under a rule exemption for fill, aggregate or clean vs. not clean? concrete to concrete recycling, and Painted concrete is considered to be clean if the 2.