Justin Woodman Dept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lovecraft's Terrestrial Terrors: Morally Alien Earthlings

7 ARTIGO http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/abusoes.2017.27816 01 LOVECRAFT’S TERRESTRIAL TERRORS: MORALLY ALIEN EARTHLINGS Greg Conley (EKU) Recebido em 05 mar 2017. Greg Conley is Adjunct Instructor of Humanities, Aprovado em 30 mar 2017 Ph.D. in Literary and Cultural Studies, MFA in Creative Writing, of the Department of Languages, Cultures, and Humanities. Expert Areas: Victorian Literature; Science Fiction/Fantasy/Horror. Email: gregory. [email protected]. Abstract: Lovecraft’s cosmic horror led him to create aliens that did not exist on the same moral spectrum as humanity. That is one of many ways Lovecraft’s work insists humans do not matter in the cosmos. However, most of the work on Lovecraft has focused on the space aliens, and how they are necessarily alien to humans, because they are from other worlds. Lovecraft’s terrestrial aliens, such as the Deep Ones, the Old Ones, and the Shoggoths, are less alien, but just as morally strange. Lovecraft used biological horror to create his terrestrial aliens, and in turn used them to claim that morality was a product of human evolution and history. A life form with a separate evolutionarily history would necessarily have a separate and incomprehensible morality. Lovecraft illustrates that point with narrators who are ultimately sympathetic with the aliens, despite the threat they pose to the narrators and to everything they have ever known. Keywords: Fiction; Cosmic horror; Biologic horror. REVISTA ABUSÕES | n. 04 v. 04 ano 03 8 ARTIGO http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/abusoes.2017.27816 Resumo: O horror cósmico de Lovecraft o conduziu a criar alienígenas que não existem no mesmo escopo moral da humanidade. -

Copyright - for the Thelemites

COPYRIGHT - FOR THE THELEMITES Downloaded from https://www.forthethelemites.website You may quote from this PDF file in printed and digital publications as long as you state the source. Copyright © Perdurabo ST, 2017 E.V. FOR THE COPYRIGHTTHELEMITES - FOR THE THELEMITES ROSE AND ALEISTER CROWLEY’S STAY IN EGYPT IN 1904 A STUDY OF THE CAIRO WORKING AND WHAT IT LED TO BY PERDURABO ST ã FRATER PERDURABO, to whom this revelation was made with so many signs and wonders, was himself unconvinced. He struggled against it for years. Not until the completion of His own initiation at the end of 1909 did He understand how perfectly He was bound to carry out this work. (Indeed, it was not until his word became conterminous with Himself and His Universe that all alien ideas lost their meaning for him). Again and again He turned away from it, took it up for a few days or hours, then laid it aside. He even attempted to destroy its value, to nullify the result. Again and again the unsleeping might of the Watchers drove Him back to the work; and it was at the very moment when He thought Himself to have escaped that He found Himself fixed for ever with no possibility of again turning aside for the fraction of a second from the path. The history of this must one day be told by a more vivid voice. Properly considered, it is a history of continuous miracle. THE EQUINOX OF THE GODS, 1936 E.V. For the Thelemites CHAPTER 6 Ì[Htp (hetep), altar] • The replica As regards the replica, which Crowley later published as a photographical colour reproduction in both TSK1912 and EG873, who was the artist? As seen above, Crowley writes in Confessions that it was a replica madeCOPYRIGHT by one of the artists attached - FOR to the THE museu m.THELEMITES.874 In fact there was an artist on the permanent staff of the museum as stated in various records. -

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the Fiction of H.P. Lovecraft

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft Daniel M. Look St. Lawrence University Introduction My cynicism and skepticism are increasing, and from an entirely new cause – the Einstein theory. The latest eclipse observations seem to place this system among the facts which cannot be dismissed, and assumedly it removes the last hold which reality or the universe can have on the independent mind. All is chance, accident, and ephemeral illusion - a fly may be greater than Arcturus, and Durfee Hill may surpass Mount Everest - assuming them to be removed from the present planet and differently environed in the continuum of space-time. All the cosmos is a jest, and fit to be treated only as a jest, and one thing is as true as another. 1 Howard Philips Lovecraft lived in a time of great scientific and mathematical advancement. The late 1800s to the early 1900s saw the discovery of x-rays, the identification of the electron, work on the structure of the atom, breakthroughs in the mathematical exploration of higher dimensions and alternate geometries, and, of course, Einstein's work on relativity. From his work on relativity, Einstein postulated that rays of light could be bent by celestial objects with a large enough gravitational pull. In 1919 and 1922 measurements were made during two eclipses that added support to this notion. This left Lovecraft unsettled, as seen in the above quote from a 1923 letter to James F. Morton. Lovecraft's distress is that it seems we can no longer trust our primary means of understanding the world around us. -

Malleus Monstrorumsampleexpanded English File Edition Is Published by Chaosium Inc

Sample file —EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION IN 380 ENTRIES— by Scott David Aniolowski with Sandy Petersen & Lynn Willis Additional Material by: David Conyers, Keith Herber, Kevin Ross, ChadSample J. Bowser, Shannon file Appel, Christian von Aster, Joachim A. Hagen, Florian Hardt, Frank Heller, Peter Schott, Steffen Schuütte, Michael Siefner, Jan Cristof Steines, Holger Göttmann, Wolfang Schiemichen, Ingo Ahrens, and friends. For fuller Author credits see pages 4 and 288. Project & Layout: Charlie Krank Cover Painting: Lee Gibbons Illustrated by: Pascal D. Bohr, Konstantyn Debus, Nils Eckhardt, Thomas Ertmer, Kostja Kleye, Jan Kluczewitz, Christian Küttler, Klaas Neumann, Patrick Strietzel, Jens Weber, Maria Luisa Witte, Lydia Ortiz, Paul Carrick. Art direction and visual concept: Konstantyn Debus (www.yllustration.com) Participants in the German Edition: Frank Heller, Konstantyn Debus, Peter Schott, Thomas M. Webhofer, Ingo Ahrens, Jens Kaufmann, Holger Göttmann, Christina Wessel, Maik Krüger, Holger Rinke, Andreas Finkernagel, 15brötchenmann Find more information at www.pegasus.de German to English Translation: Bill Walsh Layout Assistance: Alan Peña, Lydia Ortiz Chaosium is: Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, and a few odd critters. A CHAOSIUM PUBLICATION • 2006 M’bwa, megalodon, the Million Favoured Ones, the Complete Credits mind parasites, the miri nigri, M’nagalah, Mordiggian, moose, M’Tlblys, the nioth-korghai, Nug & Yeb, octo- Scott David Aniolowski: the children of Abhoth, pus, Ossadagowah, Othuum, the minions of Othuum, -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

Scintillations in Mauve

starfire2420nov.qxd 20/11/11 11:05 pm Page 9 Scintillations in Mauve An Introduction to the Work of Kenneth Grant enneth Grant was one of the most influential occultists of the 20th century. He leaves behind a substantial and formidable K body of work which will be explored and developed over the years to come. What follows here is an introductory survey of his work — a basis for deeper, more substantial consideration of his work in the future. Born in Essex in 1924, Kenneth Grant developed an intense interest in the occult from an early age, as well as a life-long devotion to Buddhism and other oriental religions. He remarked somewhere in his writings that Eastern mysticism was his first love — an indication not only of how well read he was, but more importantly perhaps his heightened sense of the immanent. Grant relates in Outside the Circles of Time how he had come across a copy of Magick in Theory and Practice — at Zwemmers, in the Charing Cross Road — in the late 1930s or early 1940s. At this period he had also discovered Austin Osman Spare’s The Book of Pleasure at Michael Houghton’s Atlantis Bookshop in Museum Street. After immersing himself in the works of Crowley, he finally managed to make contact with him in 1944, writing to the address provided in The Book of Thoth which had just been published. Visiting him several times, Grant subsequently stayed with him at ‘Netherwood’ in Hastings in 1945, immersed in Magick. Many years later, Grant wrote a memoir of this period of his life, Remembering Aleister Crowley. -

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson Introduction Sociologist Bryan R. Wilson once alleged that post-modern technology and secularisation are the allied forces of rationality and disenchantment that pose an immense threat to traditional religion.1 However, the flexibility of pastiche Neopagan belief systems like ‘Witchcraft’ have creativity, fantasy, and innovation at their core, allowing practitioners of Witchcraft to respond in a unique way to the post-modern age by integrating technology into their perception of the sacred. The phrase Deus ex Machina, the God out of the Machine, has gained a multiplicity of meanings in this context. For progressive Witches, the machine can both possess its own numen and act as a conduit for the spirit of the deities. It can also assist the practitioner in becoming one with the divine by enabling a transcendent and enlightening spiritual experience. Finally, in the theatrical sense, it could be argued that the concept of a magical machine is in fact the contrived dénouement that saves the seemingly despondent situation of a so-called ‘nature religion’ like Witchcraft in the techno-centric age. This paper explores the ways two movements within Witchcraft, ‘Technopaganism’ and ‘Technomysticism’, have incorporated man-made inventions into their spiritual practice. A study of how this is related to the worldview, operation of magic, social aspect and development of self within Witchcraft, uncovers some of the issues of longevity and profundity that this religion will face in the future. Witchcraft as a Religion The categorical heading ‘Neopagan’ functions as an umbrella that covers numerous reconstructed, revived, or invented religious movements, that have taken inspiration from indigenous, archaic, and esoteric traditions. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

OCCULT BOOKS Catalogue No

THOMPSON RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE 45 OCCULT BOOKS Catalogue No. 45. OCCULT BOOKS Folklore, Mythology, Magic, Witchcraft Issued September, 2016, on the occasion of the 30th Anniversary of the Opening of our first Bookshop in Vancouver, BC, September, 1986. Every Item in this catalogue has a direct link to the book on our website, which has secure online ordering for payment using credit cards, PayPal, cheques or Money orders. All Prices are in US Dollars. Postage is extra, at cost. If you wish to view this catalogue directly on our website, go to http://www.thompsonrarebooks.com/shop/thompson/category/Catalogue45.html Thompson Rare Books 5275 Jerow Road Hornby Island, British Columbia Canada V0R 1Z0 Ph: 250-335-1182 Fax: 250-335-2241 Email: [email protected] http://www.ThompsonRareBooks.com Front Cover: Item # 73 Catalogue No. 45 1. ANONYMOUS. COMPENDIUM RARISSIMUM TOTIUS ARTIS MAGICAE SISTEMATISATAE PER CELEBERRIMOS ARTIS HUJUS MAGISTROS. Netherlands: Aeon Sophia Press. 2016. First Aeon Sophia Press Edition. Quarto, publisher's original quarter black leather over grey cloth titled in gilt on front cover, black endpapers. 112 pp, illustrated throughout in full colour. Although unstated, only 20 copies were printed and bound (from correspondence with the publisher). Slight binding flaw (centre pages of the last gathering of pages slightly miss- sewn, a flaw which could be fixed with a spot of glue). A fine copy. ¶ A facsimile of Wellcome MS 1766. In German and Latin. On white, brown and grey-green paper. The title within an ornamental border in wash, with skulls, skeletons and cross-bones. Illustrated with 31 extraordinary water-colour drawings of demons, and three pages of magical and cabbalistic signs and sigils, etc. -

The Age of Aquarius by Don Cerow, NCGR IV

The Age of Aquarius by Don Cerow, NCGR IV Welcome to the Age of Aquarius.* We are a generation that is perched on the dawn of a new epoch, a new vibration. The world is changing. Everything from politics to industry to our mortgages turns on a new pivot, and we are lucky enough to be able to witness the unfolding. There are those who feel as though the Age has already begun. Others believe that the Age is not yet here, and the called for changes have not yet fully unfolded. Both are correct. As we look around us, electricity fills the air. Lights, power, technology, refrigeration, computers, smart phones, microchips, and science are all manifestations of the New Age at work, of a brave new world already (up and running). But the use of fossil fuels, oil, coal, and natural gas, the inability of Congress to get things done due to party allegiances, the growing intensity of storms and the general weather patterns, are all indications Alpha Piscium and Omega Piscium are the stars thought by Don Cerow that the Age of Pisces is not yet over. to observationally “benchmark” the Age of Pisces. We are building to a crescendo with the warming of the planet being the Revelation 22:13 says, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End.” When Revelation was written in the first century AD, the substantial catalyst that inaugurates “New Age” (Pisces) stretched out before them, describing what the future would hold. these changes. -

Kuhn-Conference Paper

Lina Kuhn [email protected] Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill “Affect and Deep Time in Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and the Turn Towards Thinking Through the Epoch of the Anthropocene” Mark McGurl begins his article “The Posthuman Comedy” with an analysis of a work by Wai Chee Dimock entitled Through Other Continents: American Literature across Deep Time as a way to think through the concept of deep time and its appearance in fiction. McGurl states that “the perspective of deep time holds the promise, for Dimock, of reinvigorating ‘our very sense of the connectedness among human beings’” which becomes important in, for instance, “dissuading us from the wisdom of war” (McGurl 533). I will return later to the possible benefits of thinking of the ‘connectedness among human beings,’ or as Dipesh Chakrabarty states in his article “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” “the knowledge of humans as a species,” but first I would like to explore the ways in which a work of fiction might gesture towards those benefits on its own terms (Chakrabarty 219). In 1936 H.P. Lovecraft published his novella The Shadow Over Innsmouth, a horror story told by a nameless narrator about his encounters with an alien species in an American town shunned by the rest of the country. The narrator of this tale, through the abjection and horror caused by his loss of agency in relation to the aliens and their status as other, reveals how a sense of deep time changes a human’s reactions to his situation. -

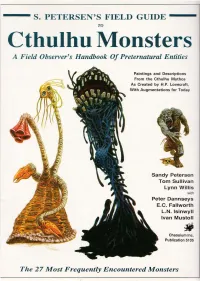

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book.