90 Can Criminology Make Sense of the Quantum Revolution?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolfgang Pauli

WOLFGANG PAULI Physique moderne et Philosophie 12 mai 1999 de Wolfgang Pauli Le Cas Kepler, précédé de "Les conceptions philosophiques de Wolfgang Pauli" 2 octobre 2002 de Wolfgang Pauli et Werner Heisenberg Page 1 sur 14 Le monde quantique et la conscience : Sommes-nous des robots ou les acteurs de notre propre vie ? 9 mai 2016 de Henry Stapp et Jean Staune Begegnungen. Albert Einstein - Karl Heim - Hermann Oberth - Wolfgang Pauli - Walter Heitler - Max Born - Werner Heisenberg - Max von… Page 2 sur 14 [Atom and Archetype: The Pauli/Jung Letters, 1932-1958] (By: Wolfgang Pauli) [published: June, 2001] 7 juin 2001 de Wolfgang Pauli [Deciphering the Cosmic Number: The Strange Friendship of Wolfgang Pauli and Carl Jung] (By: Arthur I. Miller) [published: May, 2009] 29 mai 2009 de Arthur I. Miller [(Atom and Archetype: The Pauli/Jung Letters, 1932-1958)] [Author: Wolfgang Pauli] published on (June, 2001) 7 juin 2001 Page 3 sur 14 de Wolfgang Pauli Wolfgang Pauli: Das Gewissen der Physik (German Edition) Softcover reprint of edition by Enz, Charles P. (2013) Paperback 1709 de Charles P. Enz Wave Mechanics: Volume 5 of Pauli Lectures on Physics (Dover Books on Physics) by Wolfgang Pauli (2000) Paperback 2000 Page 4 sur 14 Electrodynamics: Volume 1 of Pauli Lectures on Physics (Dover Books on Physics) by Wolfgang Pauli (2000) Paperback 2000 Journal of Consciousness Studies, Controversies in Science & the Humanities: Wolfgang Pauli's Ideas on Mind and Matter, Vol 13, No. 3,… 2006 de Joseph A. (ed.) Goguen Atom and Archetype: The Pauli/Jung Letters, 1932-1958 by Jung, C. -

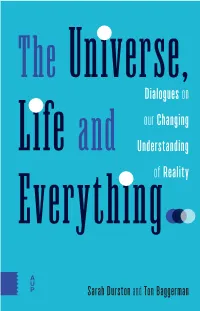

The Universe, Life and Everything…

Our current understanding of our world is nearly 350 years old. Durston It stems from the ideas of Descartes and Newton and has brought us many great things, including modern science and & increases in wealth, health and everyday living standards. Baggerman Furthermore, it is so engrained in our daily lives that we have forgotten it is a paradigm, not fact. However, there are some problems with it: first, there is no satisfactory explanation for why we have consciousness and experience meaning in our The lives. Second, modern-day physics tells us that observations Universe, depend on characteristics of the observer at the large, cosmic Dialogues on and small, subatomic scales. Third, the ongoing humanitarian and environmental crises show us that our world is vastly The interconnected. Our understanding of reality is expanding to Universe, incorporate these issues. In The Universe, Life and Everything... our Changing Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality, some of the scholars at the forefront of this change discuss the direction it is taking and its urgency. Life Understanding Life and and Sarah Durston is Professor of Developmental Disorders of the Brain at the University Medical Centre Utrecht, and was at the Everything of Reality Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in 2016/2017. Ton Baggerman is an economic psychologist and psychotherapist in Tilburg. Everything ISBN978-94-629-8740-1 AUP.nl 9789462 987401 Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman The Universe, Life and Everything… The Universe, Life and Everything… Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman AUP Contact information for authors Sarah Durston: [email protected] Ton Baggerman: [email protected] Cover design: Suzan Beijer grafisch ontwerp, Amersfoort Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. -

Proceedings of the Norbert Wiener Centenary Congress, 1994 (East Lansing, Michigan, 1994) 51 Louis H

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/psapm/052 Selected Titles in This Series 52 V. Mandrekar and P. R. Masani, editors, Proceedings of the Norbert Wiener Centenary Congress, 1994 (East Lansing, Michigan, 1994) 51 Louis H. Kauffman, editor, The interface of knots and physics (San Francisco, California, January 1995) 50 Robert Calderbank, editor, Different aspects of coding theory (San Francisco, California, January 1995) 49 Robert L. Devaney, editor, Complex dynamical systems: The mathematics behind the Mandlebrot and Julia sets (Cincinnati, Ohio, January 1994) 48 Walter Gautschi, editor, Mathematics of Computation 1943-1993: A half century of computational mathematics (Vancouver, British Columbia, August 1993) 47 Ingrid Daubechies, editor, Different perspectives on wavelets (San Antonio, Texas, January 1993) 46 Stefan A. Burr, editor, The unreasonable effectiveness of number theory (Orono, Maine, August 1991) 45 De Witt L. Sumners, editor, New scientific applications of geometry and topology (Baltimore, Maryland, January 1992) 44 Bela Bollobas, editor, Probabilistic combinatorics and its applications (San Francisco, California, January 1991) 43 Richard K. Guy, editor, Combinatorial games (Columbus, Ohio, August 1990) 42 C. Pomerance, editor, Cryptology and computational number theory (Boulder, Colorado, August 1989) 41 R. W. Brockett, editor, Robotics (Louisville, Kentucky, January 1990) 40 Charles R. Johnson, editor, Matrix theory and applications (Phoenix, Arizona, January 1989) 39 Robert L. Devaney and Linda Keen, editors, Chaos and fractals: The mathematics behind the computer graphics (Providence, Rhode Island, August 1988) 38 Juris Hartmanis, editor, Computational complexity theory (Atlanta, Georgia, January 1988) 37 Henry J. Landau, editor, Moments in mathematics (San Antonio, Texas, January 1987) 36 Carl de Boor, editor, Approximation theory (New Orleans, Louisiana, January 1986) 35 Harry H. -

Science Beyond Enchantment Revisiting the Paradigm of Re-Enchantment As an Explanatory Framework for New Age Science

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR LITTERATUR, IDÉHISTORIA OCH RELIGION Science Beyond Enchantment Revisiting the Paradigm of Re-enchantment as an Explanatory Framework for New Age Science Kristel Torgrimsson Termin VT-17 Kurs: RKT 250, 30 hp Nivå: Master Handledare: Jessica Moberg Abstract A common understanding of scientists within the New Age movement is that they are manifesting a form of re-enchantment and that their ideas should be addressed as natural theologies. This understanding often takes as its reference point, the re-entanglement of science and religion whose original separation, in this case, is often the working definition of disenchantment. This essay argues that many contemporary scientists who are both popular references and active participants on New Age conferences cannot fully be accounted for by this paradigm. Among these scientists and more particularly those interested in quantum physics, there are many who wish to extend the quantum phenomena not only to support questions of religious character, but to develop theories on physical reality and human nature. Their ambitions are not solely about merging science and religion but also about suggesting new scientific solutions and discussing scientific dilemmas. The purpose of this essay has therefore been to find a viable alternative to the re-enchantment paradigm that offers a more detailed description of their ideas. By opting instead for a radically revised re-enchantment paradigm and an anthropological suggestion for studying minor sciences, this essay has found that a more precise definition of popular New Age scientists could be as (1) “problematic” to the epistemological and ontological underpinnings of the disenchantment of the world, where the problem is not necessarily restricted to the separation of religion and science, and (2) as being a minor science, which entails a critique and challenge to state science, albeit not necessarily in terms of imposing religion on the grounds of science. -

Consciousness and the Collapse of the Wave Function∗

Consciousness and the Collapse of the Wave Function∗ David J. Chalmers† and Kelvin J. McQueen‡ †New York University ‡Chapman University May 7, 2021 Abstract Does consciousness collapse the quantum wave function? This idea was taken seriously by John von Neumann and Eugene Wigner but is now widely dismissed. We develop the idea by combining a mathematical theory of consciousness (integrated information theory) with an account of quantum collapse dynamics (continuous spontaneous localization). Simple versions of the theory are falsified by the quantum Zeno effect, but more complex versions remain compatible with empirical evidence. In principle, versions of the theory can be tested by experiments with quantum com- puters. The upshot is not that consciousness-collapse interpretations are clearly correct, but that there is a research program here worth exploring. Keywords: wave function collapse, consciousness, integrated information theory, continuous spontaneous localization ∗Forthcoming in (S. Gao, ed.) Consciousness and Quantum Mechanics (Oxford University arXiv:2105.02314v1 [quant-ph] 5 May 2021 Press). Authors are listed in alphabetical order and contributed equally. We owe thanks to audiences starting in 2013 at Amsterdam, ANU, Cambridge, Chapman, CUNY, Geneva, G¨ottingen,Helsinki, Mississippi, Monash, NYU, Oslo, Oxford, Rio, Tucson, and Utrecht. These earlier presentations have occasionally been cited, so we have made some of them available at consc.net/qm. For feedback on earlier versions, thanks to Jim Holt, Adrian Kent, Kobi Kremnizer, Oystein Linnebo, and Trevor Teitel. We are grateful to Maaneli Derakhshani and Philip Pearle for their help with the mathematics of collapse models, and especially to Johannes Kleiner, who coauthored section 5 on quantum integrated information theory. -

Physics Must Evolve Beyond the Physical

Activitas Nervosa Superior https://doi.org/10.1007/s41470-019-00042-3 IDEAS AND OPINION Physics Must Evolve Beyond the Physical Deepak Chopra1 Received: 23 July 2018 /Accepted: 27 March 2019 # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Contemporary physics finds itself pondering questions about mind and consciousness, an uncomfortable area for theorists. But historically, key figures at the founding of quantum theory assumed that reality was composed of two parts, mind and matter, which interacted with each other according to some new laws that they specified. This departure from the prior (classical- physicalist) assumption that mind was a mere side effect of brain activity was such a startling proposal that it basically split physics in two, with one camp insisting that mind will ultimately be explained via physical processes in the brain and the other camp embracing mind as innate in creation and the key to understanding reality in its completeness. Henry Stapp made important contributions toward a coherent explanation by advocating John von Neumann’s orthodox interpretation of quantum mechanics. von Neumann postulated that at its basis, quantum mechanics requires both a psychological and physical component. He was left, however, with a dualist view in which the psychological and physical aspects of QM remained unresolved. In this article, the relevant issues are laid out with the aim of finding a nondual explanation that allows mind and matter to exist as features of the same universal consciousness, in the hope that the critical insights of Planck, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, von Neumann, and Stapp will be recognized and valued, with the aim of an expanded physics that goes beyond physicalist dogma. -

From Quantum Axiomatics to Quantum Conceptuality

From Quantum Axiomatics to Quantum Conceptuality∗ Diederik Aerts1, Massimiliano Sassoli de Bianchi1,2 Sandro Sozzo3 and Tomas Veloz1,4,5 1 Center Leo Apostel for Interdisciplinary Studies, Brussels Free University Krijgskundestraat 33, 1160 Brussels, Belgium E-Mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Laboratorio di Autoricerca di Base, Lugano, Switzerland E-Mail: [email protected] 3 School of Business and IQSCS, University of Leicester University Road, LE1 7RH Leicester, United Kingdom E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Instituto de Filosof´ıa y Ciencias de la Complejidad IFICC, Los Alerces 3024, Nu˜noa,˜ Santiago, Chile 5 Departamento Ciencias Biol´ogicas, Facultad Ciencias de la vida Universidad Andres Bello, 8370146 Santiago, Chile E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract Since its inception, many physicists have seen in quantum mechanics the possibility, if not the necessity, of bringing cognitive aspects into the play, which were instead absent, or unnoticed, in the previous classical theories. In this article, we outline the path that led us to support the hypothesis that our physical reality is fundamentally conceptual-like and cognitivistic- like. However, contrary to the ‘abstract ego hypothesis’ introduced by John von Neumann arXiv:1805.12122v1 [quant-ph] 29 May 2018 and further explored, in more recent times, by Henry Stapp, our approach does not rely on the measurement problem as expressing a possible ‘gap in physical causation’, which would point to a reality lying beyond the mind-matter distinction. On the contrary, in our approach the measurement problem is considered to be essentially solved, at least for what concerns the origin of quantum probabilities, which we have reasons to believe they would be epistemic. -

Beyond Scientific Materialism

Western University Scholarship@Western Psychology Psychology 2010 Beyond Scientific aM terialism: Toward a Transcendent Theory of Consciousness Imants Barušs King's University College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/kingspsychologypub Part of the Psychology Commons Citation of this paper: Barušs, Imants, "Beyond Scientific aM terialism: Toward a Transcendent Theory of Consciousness" (2010). Psychology. 15. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/kingspsychologypub/15 Beyond Scientific Materialism: Toward a Transcendent Theory of Consciousness Imants Barušs Department of Psychology, King’s University College at The University of Western Ontario © 2010 Imants Barušs Beyond Scientific Materialism 2 Abstract Analysis of the social-cognitive substrate of scientific activity reveals that much of science functions in an inauthentic mode whereby a materialist world view constrains the authentic practice of science. But materialism cannot explain matter, as evidenced by empirical data concerning the nature of physical manifestation. Nor, then, should materialism be the basis for our interpretation of consciousness. It is time to move beyond scientific materialism and develop transcendent theories of consciousness. Such theories should minimally meet the following criteria: they should be based on all of the usual empirical data concerning consciousness, including altered states of consciousness; they should take into account data about anomalous phenomena and transcendent states of consciousness; they should address the issue of existential meaning and provide soteriological guidance; and they should be consistent with the most accurate theories of physical manifestation, such as relativistic quantum field theories. Speculating within a quantum-theoretic context, consciousness could be inserted as a primitive element into reality by providing a role for intention in the selection process of observables, the collapse of the state vector, or the ordering of quantum fluctuations. -

Quantum Approoches to Consciousness. The

UNED MASTER THESIS LOGIC, HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE (code 30001361) QUANTUM APPROACHES TO CONSCIOUSNESS. THE HYPOTHESIS OF HENRY STAPP Author: Letizia Unzain Tarantino Director: Julio C. Armero San Jose May 2013 CONTENTS: CONTENTS: ................................................... ................................................... .................................. 2 I. INTRODUCTION. CONSCIOUSNESS: CAUSALITY AND CORRELATIONS. ........................ 3 II. INTEGRATED CONSCIOUSNESS AND SUPERVENING CONSCIOUSNESS. ALVA NOË AND DAVID CHALMERS. ................................................... ................................................... .......... 4 III. THE NEW PHYSICS. ................................................... ................................................... .............. 6 IV. INTERPRETATIONS OF QUANTUM MECHANICS. THE PILOT-WAVE OF DAVID BOHM. ................................................... ................................................... ........................................... 9 IV.1 Bohm’s pilot-wave model ................................................... ................................................... 11 V. QUANTUM MECHANICS AND CONSCIOUSNESS. ................................................... ............ 13 V.1.Henry Stapp: consciousness as a dimension of reality. ................................................... ......... 13 V.1.1 The two physics: two descriptions ................................................... ................................. 13 V.1.2 The measurement postulate. -

Quantum Management: the Practices and Science of Flourishing Enterprise

Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rmsr20 Quantum management: the practices and science of flourishing enterprise Chris Laszlo To cite this article: Chris Laszlo (2020) Quantum management: the practices and science of flourishing enterprise, Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 17:4, 301-315, DOI: 10.1080/14766086.2020.1734063 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2020.1734063 Published online: 24 Feb 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 380 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rmsr20 JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT, SPIRITUALITY & RELIGION 2020, VOL. 17, NO. 4, 301–315 https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2020.1734063 Quantum management: the practices and science of flourishing enterprise Chris Laszlo Department of Organizational Behavior, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Quantum Management brings to light the power of direct- Received 22 November 2019 intuitive practices – such as meditation, nature immersion, Accepted 17 February 2020 – ’ and countless others to transform a leader sconsciousness KEYWORDS as the highest point of leverage for entrepreneurial creativity Consciousness; leadership; embedding social purpose. Layered on top of such practices flourishing; quantum; are insights from quantum physics and related disciplines that science; spirituality offer a radically different view of organizational life. Such insights help managers understand how direct-intuitive prac- tices work to change a person at the deepest level of their identity. Direct-intuitive practices give managers an experience of wholeness that heightens their awareness of how their actions impact others and the world. -

The Contributors

The Contributors Antonio Ac´ın is a Telecommunication Engineer from the Universitat Polit`ecnica de Catalunya and has a degree in Physics from the Universitat de Barcelona (UB). He got his PhD in Theoretical Physics in 2001 from the UB. After a post-doctoral stay in Geneva, in the group of Prof. Gisin (GAP-Optique), he joined the ICFO-The Institute of Photonic Sciences of Barcelona as a post-doc in 2003. He first became Assistant Profes- sor there in 2005 and later Associate Professor (April 2008). More recently, he has become an ICREA (a Cata- lan Research Institution) Research Professor, September 2008, and has been awarded a Starting Grant by the European Research Council (ERC). E-mail: [email protected] Diederik Aerts is professor at the ‘Brussels Free University (Vrije Universiteit Brussel - VUB)’ and director of the ‘Leo Apostel Centre (CLEA)’, an interdisciplinary and interuniversity (VUB, UGent, KULeuven) research centre, where researchers of dif- ferent disciplines work on interdisciplinary projects. He is also head of the research group ‘Foundations of the Exact Sciences (FUND)’ at the VUB and editor of the international journal ‘Foundations of Science (FOS)’. His work centers on the foundations of quan- tum mechanics and its interpretation, and recently he has investigated the applications of quantum structures to new domains such as cognitive science and psychology. E-mail: [email protected] 871 872 The Contributors Hanne Andersen holds a MSc in physics and comparative literature from the University of Copen- hagen and a PhD in philosophy of science from the University of Roskilde, Denmark, and she is currently associate professor at the Department for Sci- ence Studies at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. -

Beyond Scientific Materialism Toward a Transcendent Theory of Consciousness

Imants Barušs Beyond Scientific Materialism Toward a Transcendent Theory of Consciousness Abstract: Analysis of the social-cognitive substrate of scientific activ- ity reveals that much of science functions in an inauthentic mode whereby a materialist world view constrains the authentic practice of science. But materialism cannot explain matter, as evidenced by empirical data concerning the nature of physical manifestation. Nor, then, should materialism be the basis for our interpretation of con- sciousness. It is time to move beyond scientific materialism and develop transcendent theories of consciousness. Such theories should minimally meet the following criteria: they should be based on all of the usual empirical data concerning consciousness, including altered states of consciousness; they should take into account data about anomalous phenomena and transcendent states of consciousness; Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2013 they should address the issue of existential meaning and provide For personal use only -- not for reproduction soteriological guidance; and they should be consistent with the most accurate theories of physical manifestation, such as relativistic quan- tum field theories. Speculating within a quantum-theoretic context, consciousness could be inserted as a primitive element into reality by providing a role for intention in the selection process of observables, the collapse of the state vector, or the ordering of quantum fluctua- tions. But consciousness could be more fundamental, in the sense of a deep consciousness coinciding with a pre-physical substrate, from which intention shapes both mental experience and physical manifes- tation. If any significance can be attached to the mathematical for- malism of relativistic quantum field theories, perhaps creation and Correspondence: Imants Barušs, King’s University College, 266 Epworth Ave., London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 2M3 Email: [email protected] Journal of Consciousness Studies, 17,No.7–8,2010,pp.213–31 214 I.