Past Times by Ernest Griffiths.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wem and Surrounding Area Place Plan 2019/20

Wem and Surrounding Area Place Plan 2019/20 1 Contents Context What is a Place Plan? 3 Section 1 List of Projects 5 1.1 Data and information review 1.2 Prioritisation of projects 1.3 Projects for Wem and Surrounding Area Place Plan Section 2 Planning in Shropshire 18 2.1 County-wide planning processes 2.2 This Place Plan area in the county-wide plan Section 3 More about this area 23 3.1 Place Plan boundaries 3.2 Pen picture of the area 3.3 List of Parishes and Elected Members 3.4 Other local plans Section 4 Reviewing the Place Plan 26 4.1 Previous reviews 4.2 Future reviews Annexe 1 Supporting information 28 2 Context: what is a Place Plan? Shropshire Council is working to make Shropshire a great place to live, learn, work, and visit- we want to innovate to thrive. To make that ambition a reality, we need to understand what our towns and communities need in order to make them better places for all. Our Place Plans – of which there are 18 across the county – paint a picture of each local area, and help all of us to shape and improve our communities. Place Plans are therefore documents which bring together information about a defined area. The information that they contain is focussed on infrastructure needs, such as roads, transport facilities, flood defences, schools and educational facilities, medical facilities, sporting and recreational facilities, and open spaces. They also include other information which can help us to understand local needs and to make decisions. -

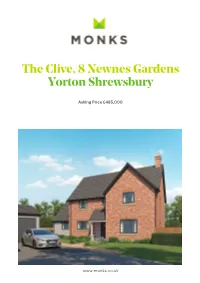

Vebraalto.Com

The Clive, 8 Newnes Gardens Yorton Shrewsbury Asking Price £485,000 www.monks.co.uk *** THE JEWEL IN THE CROWN *** ON THIS SELECT COURTYARD OF JUST 9 HOMES - NEWNES GARDENS. LIVE, WORK AND PLAY - THIS IS THE MOST PERFECT VERSATILE HOME FOR TODAY'S MODERN LIFESTYLE A fabulous double fronted Detached home being finished to an exacting standard of specification by reputable local developers Montford Properties. Ideal for a growing family, those who love to entertain, work from home or just require space. A MUST VIEW - contact [email protected] 07890 573553 The location Occupying an enviable position on the edge of Yorton which lies on the edge of the much sought after Village of Clive where you will find amenities including School, General Store and Church. There is a regular bus service to the Town Centre along with Railway Station with links to Shrewsbury and Crewe. The busy North Shropshire market town of Wem is a short distance away where you will find a host of facilities and the County Town of Shrewsbury is appoximately 7 miles distant. The features • STUNNING BRAND NEW DETACHED HOME • BORDERED BY WOOD AND FARMLAND • FABULOUS COURTYARD LOCATION • FINISHED TO CONTEMPORARY SPECIFICATION • LOUNGE WITH INGLENOOK • BEAUTIFUL OPEN PLAN LIVING/DINING/KITCHEN • FAMILY ROOM AND GARDEN ROOM • 4 DOUBLE BEDROOMS 3 BATHROOMS • DOUBLE GARAGE AND GARDENS • MUCH SOUGHT AFTER VILLAGE Judy Bourne Director at Monks [email protected] Monks for themselves and for the vendors of this property, whose agents they are give notice that: • These particulars provide a general outline only for the guidance of intended purchasers and do not Get in touch constitute part of an offer or contract. -

Rural Settlement List 2014

National Non Domestic Rates RURAL SETTLEMENT LIST 2014 1 1. Background Legislation With effect from 1st April 1998, the Local Government Finance and Rating Act 1997 introduced a scheme of mandatory rate relief for certain kinds of hereditament situated in ‘rural settlements’. A ‘rural settlement’ is defined as a settlement that has a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable year in question. The Non-Domestic Rating (Rural Settlements) (England) (Amendment) Order 2009 (S.I. 2009/3176) prescribes the following hereditaments as being eligible with effect from 1st April 2010:- Sole food shop within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole general store within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole post office within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole public house within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Sole petrol filling station within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Section 47 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 provides that a billing authority may grant discretionary relief for hereditaments to which mandatory relief applies, and additionally to any hereditament within a rural settlement which is used for purposes which are of benefit to the local community. Sections 42A and 42B of Schedule 1 of the Local Government and Rating Act 1997 dictate that each Billing Authority must prepare and maintain a Rural Settlement List, which is to identify any settlements which:- a) Are wholly or partly within the authority’s area; b) Appear to have a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable financial year in question; and c) Are, in that financial year, wholly or partly, within an area designated for the purpose. -

Oswestry Group Programme & Newsletter

Oswestry Group Programme & Newsletter November 2017 to February 2018 page 1 page 2 Chairman’s Chat As many of you will know I am coming to the end of my term as your Chairperson after four years, so we are looking for someone to come forward and volunteer to be our next chairperson. I would like to thank three groups of people who have helped to make my job pleasant and enjoyable. To all members of Oswestry Ramblers for their support and encouragement, to all the walk leaders for their time and effort in giving us such a varied and interesting programme and to the members of the committee, past and present, for their support and work during my four years, so THANK YOU TO YOU ALL. The AGM is set for Tuesday 28 November, 7.15pm, at Whittington Cricket Club. Please come and see if we can have more members there than ever. The new walks programme is out and if there are any dates vacant, apart from those over Christmas, that will be due to the programme co-ordinators having less walks offered as our pool of walk leaders is diminished. We need members to see if they have a favourite walk they would like to offer to lead for the next programme. Thank you all once again and have good walking. Colin Chandler, Chair of Oswestry Ramblers Area News This will be replaced with a regular half-yearly newsletter. Dates for Your Diary • 28TH NOVEMBER 2017 GROUP AGM 7 pm for 7.15 pm at the Whittington Cricket Club. -

Whitchurch to Shrewsbury

Leaflet Ref. No: NCN4D/July 2013 © Shropshire Council July 2013 July Council Shropshire © 2013 NCN4D/July No: Ref. Leaflet Designed by Salisbury NORTH SHROPSHIRE NORTH MA Creative Stonehenge •www.macreative.co.uk Transport for Department the by funded Part Marlborough 0845 113 0065 113 0845 Sustrans Sustrans www.sustrans.org.uk www.sustrans.org.uk www.wiltshire.gov.uk www.wiltshire.gov.uk by the charity Sustrans. charity the by % 01225 713404 01225 Swindon Wiltshire Council Wiltshire one of the award-winning projects coordinated coordinated projects award-winning the of one This route is part of the National Cycle Network, Network, Cycle National the of part is route This National Cycle Network Cycle National gov.uk/cycling Cirencester www.gloucestershire. Telford and Wrekin 01952 202826 202826 01952 Wrekin and Telford % 01452 425000 01452 County Council County For detailed local information, see cycle map of of map cycle see information, local detailed For Gloucestershire Gloucestershire 01743 253008 01743 Gloucester Shropshire Council Council Shropshire gov.uk/cms/cycling.aspx www.travelshropshire.co.uk www.travelshropshire.co.uk www.worcestershire. Worcester % 01906 765765 01906 ©Rosemary Winnall ©Rosemary County Council County Worcestershire Worcestershire Bewdley www.telford.gov.uk % 01952 380000 380000 01952 Council Bridgnorth Telford & Wrekin Wrekin & Telford co.uk Shrewsbury to Whitchurch to Shrewsbury www.travelshropshire. Ironbridge % 01743 253008 253008 01743 bike tracks in woods and forests. and woods in tracks bike Shropshire -

Cromwelliana the Journal of the Cromwell Association

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 1999 • =-;--- ·- - ~ -•• -;.-~·~...;. (;.,, - -- - --- - -._ - - - - - . CROMWELLIANA 1999 The Cromwell Association edited by Peter Gaunt President: Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FRHistS Vice Presidents: Baron FOOT of Buckland Monachorum CONTENTS Right Hon MICHAEL FOOT, PC Professor IV AN ROOTS, MA, FSA, FRHistS Cromwell Day Address 1998 Professor AUSTIN WOOLRYCH, MA, DLitt, FBA 2 Dr GERALD AYLMER, MA, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS By Roy Sherwood Miss PAT BARNES Mr TREWIN COPPLESTONE, FRGS Humphrey Mackworth: Puritan, Republican, Cromwellian Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS By Barbara Coulton 7 Honorary Secretary: Mr Michael Byrd Writings and Sources III. The Siege. of Crowland, 1643 5 Town Fann Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEI I 3SG By Dr Peter Gaunt 24 Honorary Treasurer: Mr JOHN WESTMACOTT Cavalry of the English Civil War I Salisbury Close, Wokingham, Berkshire, RG41 4AJ I' By Alison West 32 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan statesman, and to Oliver Cromwell, Kingship and the encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is Humble Petition and Advice neither political nor sectarian, its aims being essentially historical. The Association By Roy Sherwood 34 seeks to advance its aims in a variety of ways which have included: a. the erection of commemorative tablets (e.g. at Naseby, Dunbar, Worcester, Preston, etc) (From time to time appeals are made for funds to pay for projects of 'The Flandric Shore': Cromwellian Dunkirk this sort); By Thomas Fegan 43 b. helping to establish the Cromwell Museum in the Old Grammar School at Huntingdon; Oliver Cromwell c. -

The Sheriffs of Shropshire," Has Entered at Considerable Length Into the History of the Ancient Family of Thynne, Otherwise Botfield, Or Botevyle

468 THE FAMILY OF 'l'HYNNE, OTHERWISE BO'l'FIELD. THE Rev. J. B. Blakeway, in his account of "The Sheriffs of Shropshire," has entered at considerable length into the history of the ancient family of Thynne, otherwise Botfield, or Botevyle. He has correctly discarded the idea, originating with Matthew Paris, that the first recorded ancestor of this family, Geoffrey Botevile, was a native of Poictou, and that he settled on lands in Stretton, in the county of Salop, given him by the Earl of Arundel,' .and which lands were afterwards called by his name of Botevile: the fact being that the family, instead of giving their name to the place, derived their surname there• from; and the various members thereof are, upon all the ancient Court Rolls of the manor of Stretton, described as Bottefeld of Bottefeld, although in later years the branch of the family which continued to reside there adopted the orthography of Botevyle, by which name the place itself is now usually known. Mr. Blakeway himself has, however, fallen into several errors in the detail of the family; and his admission that Sir Ralph de Theyne, knight, who was examined in the great plea of arms, Lovel v. Morley, in 1395, might have belonged to this house was certainly made without any sufficient reason : for the name of Thynne was unknown in this distinguished Shrop• shire family until after the division of the family estates in the manor of Stretton in 1439, when Thomas Bottefeld settled his copyhold lands at Bottefeld upon his younger son John Botte• feld, the ancestor of the line thereafter resident on that estate, and his eldest son William Bottefeld adopted for his residence the mansion or inn a at Stretton, to which the freehold lands of the family, with various detached copyholds, were attached, and thus formed a separate estate and residence for himself and his descendants. -

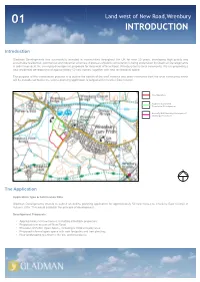

Introduction

01 Land west of New Road,Wrenbury INTRODUCTION Introduction Gladman Developments has successfully invested in communities throughout the UK for over 20 years, developing high quality and sustainable residential, commercial and industrial schemes. A process of public consultation is being undertaken by Gladman Developments in order to present the emerging development proposals for land west of New Road, Wrenbury to the local community. We are proposing a new residential development of approximately 50 new homes, together with new recreational space. The purpose of this consultation process is to outline the details of the draft scheme and seek comments from the local community which will be considered before the outline planning application is lodged with Cheshire East Council. Site Boundary Adjacent Consented Residential Development Recently Built Housing Development (St Margarets Close) N The Application Application Type & Submission Date Gladman Developments intends to submit an outline planning application for approximately 50 new homes to Cheshire East Council in Autumn 2016. This would establish the principle of development. Development Proposals • Approximately 50 new homes, including affordable properties; • Proposed new access off New Road; • Provision of Public Open Space, including a children’s play area; • Proposed informal open space with new footpaths and tree planting; • New landscaping to enhance the site and boundaries. 02 Land west of New Road,Wrenbury HOUSING NEED Housing Need Every Council is required by the Government to boost significantly the supply of housing and to make planning decisions in the light of a presumption in favour of sustainable development. Cheshire East Council is required to provide enough housing land to meet its full future housing needs. -

Old Houses Shrewsbury

Old H ou se s Sh rewsbu ry THEIR HISTORY AND ASSOCIATIONS . O R H . E F R EST , Val l e lu o . c Ca mdoc a nd S r n l d b H n S e . eve y C , “ ’ ‘ A uthor o the Fa una o Nor th W a les F a un a o S ho slz z re etc . f f ' f p , 1 1 9 1 . W S on m e e e . ilding , Li it d , Print rs , Shr wsbury P R E F A C E . LTHOUGH many books dealing with the history or 2 topography of Shrewsbury have appeared from time m work t o to ti e , no devoted the history of its old I houses has hitherto been published . n the present volume I h a ve tried to give a succinct a ccount of these in terestin g — ’ old buildings Shrewsbury s most a ttractive feature l a m partly by co lating all available dat regarding the , and partly by careful study and comparison of the structures themselves . The principal sources of information as to their past ’ history are Owen an d Bl akeway s monument a l History of S hrewsbur y , especially the numerous footnotes therein the Tra n sa ction s of the S hropshir e A r chwol ogica l S oc iety in clud ’ n d Bl k M S . a a ewa s ing the famous Taylor . y Topo ’ graphical History oi Shrewsbury Owen s A c coun t of S hrewsbury published an onymously in 1 80 8 S hropshir e Notes a n d Quer ies reprinted from the Shrewsbury Chr on i cle and S hr eds a n d P a tches a similar series of earlier ’ ’ date from Eddowes Journal . -

2.1 the Liberties and Municipal Boundaries.Pdf

© VCH Shropshire Ltd 2020. This text is supplied for research purposes only and is not to be reproduced further without permission. VCH SHROPSHIRE Vol. VI (ii), Shrewsbury Sect. 2.1, The Liberties and Municipal Boundaries This text was originally drafted by the late Bill Champion in 2012. It was lightly revised by Richard Hoyle in the summer and autumn of 2020. The text on twentieth-century boundary changes is his work. The final stages of preparing this version of the text for web publication coincided with the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020. It was not possible to access libraries and archives to resolve a small number of outstanding queries. When it becomes possible again, it is proposed to post an amended version of this text on the VCH Shropshire website. In the meantime we welcome additional information and references, and, of course, corrections. In some cases the form of references has been superseded. Likewise, some cross-references are obsolete. It is intended that this section will be illustrated by a map showing the changing boundary which will be added into the text at a later date. October 2020 © VCH Shropshire Ltd 2020. This text is supplied for research purposes only and is not to be reproduced further without permission. 1 © VCH Shropshire Ltd 2020. This text is supplied for research purposes only and is not to be reproduced further without permission. 2.1. The Liberties and Municipal Boundaries The Domesday ‘city’ (civitas) of Shrewsbury included nine hides identifiable as the townships of its original liberty. To the south of the Severn they included Sutton, Meole Brace, Shelton, and Monkmeole (Crowmeole), and to the north Hencott.1 The location of a further half-hide, belonging to St Juliana’s church, was described by Eyton as ‘doubtful’,2 but may refer to the detached portions of St Juliana’s in Shelton.3 More obscure, as leaving no later parochial trace, was a virgate in Meole Brace which belonged to St Mary’s church.4 The Domesday liberties, however, were not settled. -

01743 236444 for Sale

FOR SALE Bethany, Wem Road, Clive, Shrewsbury, SY4 3JH FOR SALE Offers in the region of £349,000 Indicative floor plans only - NOT TO SCALE - All floor plans are included only as a guide Bethany, Wem Road, Clive, and should not be relied upon as a source of information for area, measurement or detail. Shrewsbury, SY4 3JH Energy Performance Ratings Property to sell? We would be who is authorised and regulated delighted to provide you with a free by the FCA. Details can be no obligation market assessment provided upon request. Do you of your existing property. Please require a surveyor? We are contact your local Halls office to able to recommend a completely A mature detached cottage of character with pretty gardens, stables/barn and make an appointment. Mortgage/ independent chartered surveyor. grazing land enjoying extensive farmland views just outside the sought after financial advice. We are able Details can be provided upon to recommend a completely request. village of Clive. In all about 2.34 acres. independent financial advisor, 01743 236444 Shrewsbury office: 2 Barker Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY1 1QJ E. [email protected] IMPORTANT NOTICE. Halls Holdings Ltd and any joint agents for themselves, and for the Vendor of the property whose Agents they are, give notice that: (i) These particulars are produced in good faith, are set out as a general guide only and do not constitute any part of a contract (ii) No person in the employment of or any agent of or consultant to Halls Holdings has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty whatsoever in relation to this property (iii) Measurements, areas and distances are approximate, Floor plans and photographs are for guidance purposes only (photographs are taken with a wide angled / zoom lenses) and dimensions shapes and precise locations may differ (iv) It must not be assumed that the property has all the required planning or building regulation consents. -

Core Strategy

Shropshire Local Development Framework : Adopted Core Strategy March 2011 “A Flourishing Shropshire” Shropshire Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Spatial Portrait 7 Shropshire in 2010 7 Communities 9 Economy 10 Environment 13 Spatial Zones in Shropshire 14 3 The Challenges We Face 27 Spatial Vision 28 Strategic Objectives 30 4 Creating Sustainable Places 34 Policy CS1: Strategic Approach 35 Policy CS2: Shrewsbury Development Strategy 42 Policy CS3: The Market Towns and Other Key Centres 48 Policy CS4: Community Hubs and Community Clusters 61 Policy CS5: Countryside and Green Belt 65 Policy CS6: Sustainable Design and Development Principles 69 Policy CS7: Communications and Transport 73 Policy CS8: Facilities, Services and Infrastructure Provision 77 Policy CS9: Infrastructure Contributions 79 5 Meeting Housing Needs 82 Policy CS10: Managed Release of Housing Land 82 Policy CS11: Type and Affordability of Housing 85 Policy CS12: Gypsies and Traveller Provision 89 6 A Prosperous Economy 92 Policy CS13: Economic Development, Enterprise and Employment 93 Policy CS14: Managed Release of Employment Land 96 Policy CS15: Town and Rural Centres 100 Policy CS16: Tourism, Culture and Leisure 104 7 Environment 108 Policy CS17: Environmental Networks 108 Policy CS18: Sustainable Water Management 111 Policy CS19: Waste Management Infrastructure 115 Policy CS20: Strategic Planning for Minerals 120 Contents Page 8 Appendix 1: Saved Local and Structure Plan Policies replaced by the Core Strategy 126 9 Glossary 138