Pension Scheme Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

The Factory, Manchester

THE FACTORY, MANCHESTER The Factory is where the art of the future will be made. Designed by leading international architectural practice OMA, The Factory will combine digital capability, hyper-flexibility and wide open space, encouraging artists to collaborate in new ways, and imagine the previously unimagined. It will be a new kind of large-scale venue that combines the extraordinary creative vision of Manchester International Festival (MIF) with the partnerships, production capacity and technical sophistication to present innovative contemporary work year-round as a genuine cultural counterweight to London. It is scheduled to open in the second half of 2019. The Factory will be a building capable of making and presenting the widest range of art forms and culture plus a rich variety of technologies: film, TV, media, VR, live relays, and the connections between all of these – all under one roof. With a total floor space in excess of 15,000 square meters, high-spec tech throughout, and very flexible seating options, The Factory will be a space large enough and adaptable enough to allow more than one new work of significant scale to be shown and/or created at the same time, accommodating combined audiences of up to 7000. It will be able to operate as an 1800 seat theatre space as well as a 5,000 capacity warehouse for immersive, flexible use - with the option for these elements to be used together, or separately, with advanced acoustic separation. It will be a laboratory as much as a showcase, a training ground as well as a destination. Artists and companies from across the globe, as well as from Manchester, will see it as the place where they can explore and realise dream projects that might never come to fruition elsewhere. -

ITV Plc Corporate Responsibility Report 04 ITV Plc Corporate Responsibility Report 04 Corporate Responsibility and ITV

One ITV ITV plc Corporate responsibility report 04 ITV plc Corporate responsibility report 04 Corporate responsibility and ITV ITV’s role in society is defined ITV is a commercial public service by the programmes we make broadcaster. That means we and broadcast. The highest produce programmes appealing ethical standards are essential to to a mass audience alongside maintaining the trust and approval programmes that fulfil a public of our audience. Detailed rules service function. ITV has three core apply to the editorial decisions public service priorities: national we take every day in making and international news, regional programmes and news bulletins news and an investment in and in this report we outline the high-quality UK-originated rules and the procedures in place programming. for delivering them. In 2004, we strengthened our longstanding commitment to ITV News by a major investment in the presentation style. Known as a Theatre of News the new format has won many plaudits and helped us to increase our audience. Researched and presented by some of the finest journalists in the world, the role of ITV News in providing accurate, impartial news to a mass audience is an important social function and one of which I am proud. Our regional news programmes apply the same editorial standards to regional news stories, helping communities to engage with local issues and reinforcing their sense of identity. Contents 02 Corporate responsibility management 04 On air – responsible programming – independent reporting – reflecting society – supporting communities – responsible advertising 14 Behind the scenes – encouraging creativity – our people – protecting the environment 24 About ITV – contacts and feedback Cover Image: 2004 saw the colourful celebration of a Hindu Wedding on Coronation Street, as Dev and Sunita got married. -

Sandyblue TV Channel Information

Satellite TV / Cable TV – Third Party Supplier Every property is privately owned and has different TV subscriptions. In most properties in the area of Quinta do Lago and Vale do Lobo it is commonly Lazer TV system. The Lazer system has many English and European channels. A comprehensive list is provided below. Many other properties will have an internet based subscription for UK programs, similar to a UK Freeview service. There may not be as many options for sports and movies but will have a reasonable selection of English language programs. If the website description for a property indicates Satellite television, for example Portuguese MEO service (visit: https://www.meo.pt/tv/canais-servicos-tv/lista-de-canais/fibra for the current list of channels) you can expect to receive at least one free to air English language channel. Additional subscription channels such as sports and movies may not be available unless stated in the property description. With all services it is unlikely that a one off payment can be made to access e.g. boxing or other pay per view sport events. If there is a specific sporting event that will be held while you are on holiday please check with us as to the availability of upgrading the TV service. A selection of our properties may be equipped to receive local foreign language channels only please check with the Reservations team before booking about the TV programs available in individual properties. If a villa is equipped with a DVD player or games console, you may need to provide your own DVDs or games. -

Broadcasting in Transition

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Broadcasting in transition Third Report of Session 2003–04 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 February 2004 HC 380 [incorporating HC101-i and HC132-i] Published on 4 March 2004 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £15.50 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Gerald Kaufman MP (Labour, Manchester Gorton) (Chairman) Mr Chris Bryant MP (Labour, Rhondda) Mr Frank Doran MP (Labour, Aberdeen Central) Michael Fabricant MP (Conservative, Lichfield) Mr Adrian Flook MP (Conservative, Taunton) Mr Charles Hendry MP (Conservative, Wealden) Alan Keen MP (Labour, Feltham and Heston) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Ms Debra Shipley (Labour, Stourbridge) John Thurso MP (Liberal Democrat, Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross) Derek Wyatt MP (Labour, Sittingbourne and Sheppey) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/culture__media_and_sport. cfm Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Fergus Reid (Clerk), Olivia Davidson (Second Clerk), Grahame Danby (Inquiry Manager), Anita Fuki (Committee Assistant) and Louise Thomas (Secretary). -

TV & Radio Channels Astra 2 UK Spot Beam

UK SALES Tel: 0345 2600 621 SatFi Email: [email protected] Web: www.satfi.co.uk satellite fidelity Freesat FTA (Free-to-Air) TV & Radio Channels Astra 2 UK Spot Beam 4Music BBC Radio Foyle Film 4 UK +1 ITV Westcountry West 4Seven BBC Radio London Food Network UK ITV Westcountry West +1 5 Star BBC Radio Nan Gàidheal Food Network UK +1 ITV Westcountry West HD 5 Star +1 BBC Radio Scotland France 24 English ITV Yorkshire East 5 USA BBC Radio Ulster FreeSports ITV Yorkshire East +1 5 USA +1 BBC Radio Wales Gems TV ITV Yorkshire West ARY World +1 BBC Red Button 1 High Street TV 2 ITV Yorkshire West HD Babestation BBC Two England Home Kerrang! Babestation Blue BBC Two HD Horror Channel UK Kiss TV (UK) Babestation Daytime Xtra BBC Two Northern Ireland Horror Channel UK +1 Magic TV (UK) BBC 1Xtra BBC Two Scotland ITV 2 More 4 UK BBC 6 Music BBC Two Wales ITV 2 +1 More 4 UK +1 BBC Alba BBC World Service UK ITV 3 My 5 BBC Asian Network Box Hits ITV 3 +1 PBS America BBC Four (19-04) Box Upfront ITV 4 Pop BBC Four (19-04) HD CBBC (07-21) ITV 4 +1 Pop +1 BBC News CBBC (07-21) HD ITV Anglia East Pop Max BBC News HD CBeebies UK (06-19) ITV Anglia East +1 Pop Max +1 BBC One Cambridge CBeebies UK (06-19) HD ITV Anglia East HD Psychic Today BBC One Channel Islands CBS Action UK ITV Anglia West Quest BBC One East East CBS Drama UK ITV Be Quest Red BBC One East Midlands CBS Reality UK ITV Be +1 Really Ireland BBC One East Yorkshire & Lincolnshire CBS Reality UK +1 ITV Border England Really UK BBC One HD Channel 4 London ITV Border England HD S4C BBC One London -

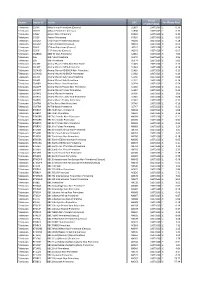

S1867 16071609 0

Period Domain Station ID Station UDC Per Minute Rate (YYMMYYMM) Television CSTHIT 4Music Non-Primetime (Census) S1867 16071609 £ 0.36 Television CSTHIT 4Music Primetime (Census) S1868 16071609 £ 0.72 Television C4SEV 4seven Non-Primetime F0029 16071608 £ 0.30 Television C4SEV 4seven Primetime F0030 16071608 £ 0.60 Television CS5USA 5 USA Non-Primetime (Census) H0010 16071608 £ 0.28 Television CS5USA 5 USA Primetime (Census) H0011 16071608 £ 0.56 Television CS5LIF 5* Non-Primetime (Census) H0012 16071608 £ 0.34 Television CS5LIF 5* Primetime (Census) H0013 16071608 £ 0.67 Television CSABNN ABN TV Non-Primetime S2013 16071608 £ 7.05 Television 106 alibi Non-Primetime S0373 16071608 £ 2.52 Television 106 alibi Primetime S0374 16071608 £ 5.03 Television CSEAPE Animal Planet EMEA Non-Primetime S1445 16071608 £ 0.10 Television CSEAPE Animal Planet EMEA Primetime S1444 16071608 £ 0.19 Television CSDAHD Animal Planet HD EMEA Non-Primetime S1483 16071608 £ 0.10 Television CSDAHD Animal Planet HD EMEA Primetime S1482 16071608 £ 0.19 Television CSEAPI Animal Planet Italy Non-Primetime S1530 16071608 £ 0.08 Television CSEAPI Animal Planet Italy Primetime S1531 16071608 £ 0.16 Television CSANPL Animal Planet Non-Primetime S0399 16071608 £ 0.54 Television CSDAPP Animal Planet Poland Non-Primetime S1556 16071608 £ 0.11 Television CSDAPP Animal Planet Poland Primetime S1557 16071608 £ 0.22 Television CSANPL Animal Planet Primetime S0400 16071608 £ 1.09 Television CSAPTU Animal Planet Turkey Non-Primetime S1946 16071608 £ 0.08 Television CSAPTU Animal -

Tim Farron MP

Response to consultation – localness on commercial radio Here in the Lake District, many people rely on local radio to stay in touch with what’s going on in their area. The area is chucked into the large North West areas by both BBC TV and ITV where stories and events in Cumbria struggle to compete with news coming out of Manchester, Liverpool and the big Lancashire cities which have little or no impact on people’s lives back home. As a result, people in the Lake District listen to local radio primarily because it is just that – local. By significantly reducing the number of hours that concern news which affects them, or which sees a presenter talk about things they can identify with, local radio stations will just end up being an inferior version of national stations and so listeners will just change over and listen to the real thing instead of a substandard substitute. Ofcom’s proposals would not allow for a local breakfast and drivetime shows. These are well known to be the two most listened to slots of the day and by sacrificing one of the two to national programming, then the station will lose purpose, credibility and, as a result, listeners. Seven hours of locally produced content per weekday must be retained, including provision at breakfast time. The Ofcom proposals are based loosely on the ITV regions. As a result, the Lake District is thrown into the ITV Granada region. Such a large area simply could not be accommodated into local radio. As stated previously, news coming out of Manchester, Liverpool and the big Lancashire cities which have little or no impact on people’s lives in Cumbria and vice-versa. -

ITV Plc Corporate Responsibility Report 2006 Airing the Issues

ITV plc Corporate responsibility report 2006 Airing the issues. Message from the Executive Chairman Michael Grade I have discovered many good things about ITV in the few months since I joined. Something I was particularly pleased to find is the Company’s strong commitment to corporate responsibility. ITV plc is a leading UK media company, owning all of the Contents regional Channel 3 licences in England and Wales. ITV owns Message from the Executive Chairman 01 free-to-air digital channels ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV4, Citv and Corporate responsibility management 08 Men & Motors. ITV is now available on every major platform, including broadcast TV, online and on mobile. The Company’s production arm (ITV Productions) is the biggest commercial On air television production company in the UK and one of Europe’s Responsible programming 10 largest programme distributors. Independent reporting 14 Reflecting society 16 Supporting communities 20 Scope of this report Responsible advertising 22 This report covers ITV’s core activities during the calendar year 2006. Behind the scenes Further information Further information on ITV’s non-financial KPI’s and related data Creative economy 24 is available in the Business Review section of our 2006 Annual Report, Protecting the environment 26 available to download on our website. Our people 28 Health and safety 32 More online a To find out more about the topics contained in this report, please visit www.itvplc.com/itv/responsibility. About ITV Performance indicators 33 Cover image CR objectives 34 ITV News anchor Mark Austin broadcasting from Antarctica. See page 6 for details. -

Social Purpose Report 2018 1

ITV SOCIAL PURPOSE REPORT 2018 1 Contents Welcome Welcome to ITV’s Social Purpose report. 01 Welcome 18 People 02 About ITV 25 Responsible business 03 How we do business 26 Awards 04 Highlights 28 Looking ahead 06 Partnerships 30 Performance data 12 Planet Contact Us [email protected] 020 7157 3160 @ITVPurpose ITV is more than TV. Every day we male suicide rates through Project inclusion within and beyond ITV, from entertain millions, grow brands and 84 – our award-winning initiative with Lost Voice Guy winning Britain’s Got shape culture for good. We reach CALM – and our work promoting the Talent and Anne Hegarty discussing her vast audiences and build connections Daily Mile in 2018 contributed to over autism in I’m a Celebrity...Get Me Out through our programmes and 750,000 more schoolchildren running of Here, to our own internal networks platforms. In 2018, we made 8,900 a mile every day. supporting BAME, LGBT+ and female hours of programming, and employed colleagues, and work-life balance. over 6,100 people. This gives us an We became a carbon-neutral business, extraordinary opportunity to make a and reduced the impact that our In 2019 we are launching new targets difference to issues that are important shows have on the planet. Coronation for Social Purpose as a core element to our viewers and to society. We do Street and Emmerdale continue to of our strategy – see page 28 for this both on-screen through informing champion sustainable behaviours more details. Our redefined priorities and inspiring our viewers and off-screen on-screen, and we made it compulsory are championing better mental and through our employees and our actions. -

Free to Air Satellite and Saorview Channels

Free to Air Satellite and Saorview Channels Note* An Aerial is needed to receive Saorview Saorview Channels News Music Entertainment RTÉ One HD Al Jazeera English Bliss ?TV Channel 4 +1 OH TV RTÉ Two HD Arise News The Box 4seven Channel 4 HD Pick TV3 BBC News Capital TV 5* Channel 5 Pick +1 TG4 BBC News HD Channel AKA 5* +1 Channel 5 +1 Propeller TV UTV Ireland BBC Parliament Chart Show Dance 5USA Channel 5 +24 Property Show RTÉ News Now Bloomberg Television Chart Show TV 5USA +1 E4 Property Show +2 3e BON TV Chilled TV ABN TV E4 +1 Property Show +3 RTÉjr CCTV News Clubland TV The Africa Channel Fashion One S4C RTÉ One + 1 Channels 24 Flava BBC One Food Network Showbiz TV RTÉ Digital Aertel CNBC Europe Heart TV BBC One HD Food Network +1 Showcase CNC World Heat BBC Two Forces TV Spike Movies CNN International Kerrang! BBC Two HD[n 1] FoTV Travel Channel Film4 Euronews Kiss BBC Three Holiday & Cruise Travel Channel +1 Film4 +1 France 24 Magic BBC Three HD Horse & Country TV True Drama Horror Channel NDTV 24x7 Now Music BBC Four Information TV True Entertainment Horror Channel +1 NHK World HD Scuzz BBC Four HD Irish TV TruTV Movies4Men RT Smash Hits BBC Alba ITV (ITV/STV/UTV) TruTV +1 Movies4Men +1 RT HD Starz TV BEN ITV +1 Vox Africa Talking Pictures TV Sky News The Vault BET ITV HD / STV HD / UTV HD True Movies 1 TVC News Vintage TV CBS Action ITV2 True Movies 2 TVC News +1 Viva CBS Drama ITV2 +1 More>Movies Children Children CBS Reality ITV3 More>Movies +1 CBBC Kix CBS Reality +1 ITV3 +1 CBBC HD Kix +1 Challenge ITV4 Documentaries CBeebies -

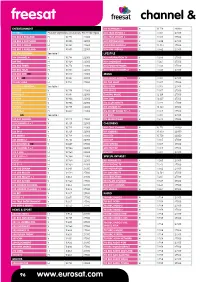

Freesat Channel & Frequency Listings

freesat channel & frequency listings ENTERTAINMENT 301 FILMFOUR+1 H 10.714 22000 101 BBC 1 Postcode dependant see channels 950-971 for region 302 TRUE MOVIES 1 V 11.307 27500 102 BBC 2 ENGLAND H 10.773 22000 303 TRUE MOVIES 2 V 11.307 27500 102 BBC 2 SCOTLAND H 10.803 22000 304 MOVIES4MEN V 11.224 27500 102 BBC 2 WALES H 10.803 22000 304 MOVIES4MEN+1 H 12.523 27500 102 BBC 2 N.IRELAND H 10.803 22000 308 UMP MOVIES H 11.662 27500 103 ITV1 REGIONAL See table 1 LIFESTYLE 104 CHANNEL 4 V 10.714 22000 402 INFORMATION TV V 11.680 27500 105 FIVE H 10.964 22000 403 SHOWCASE V 11.261 27500 106 BBC THREE H 10.773 22000 405 FOOD NETWORK H 11.343 27500 107 BBC FOUR H 10.803 22000 406 FOOD NETWORK+1 H 11.343 27500 108 BBC ONE HD V 10.847 23000 MUSIC 109 BBC HD V 10.847 23000 500 CHART SHOW TV V 11.307 27500 110 BBC ALBA H 11.954 27500 501 THE VAULT V 11.307 27500 112 ITV1+1 REGIONAL See table 1 502 FLAVA V 11.307 27500 113 ITV2 V 10.758 22000 503 SCUZZ V 11.307 27500 114 ITV2+1 H 10.891 22000 504 B4U MUSIC V 12.129 27500 115 ITV3 V 10.906 22000 509 ZING V 12.607 27500 116 ITV3+1 V 10.906 22000 514 CLUBLAND TV H 11.222 27500 117 ITV4 V 10.758 22000 515 VINTAGE TV H 12.523 27500 118 ITV4+1 H 10.832 22000 516 CHART SHOW TV + 1 V 11.307 27500 119 ITV HD See table 1 517 BLISS V 11.307 27500 120 S4C DIGIDOL V 12.129 27500 518 MASSIVE R&B H 11.623 27500 121 CHANNEL 4 + 1 V 10.729 22000 CHILDRENS 122 E4 V 10.729 22000 600 CBBC CHANNEL H 10.773 22000 123 E4+1 V 10.729 22000 601 CBEEBIES H 10.803 22000 124 MORE4 V 10.729 22000 602 CITV V 10.758 22000 125 MORE4+1