Ncomms12257.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3-D Seismic Characterization of a Cryptoexplosion Structure

Cryptoexplosion structure 3-D seismic characterization of a eryptoexplosion structure J. Helen Isaac and Robert R. Stewart ABSTRACT Three-quarters of a circular structure is observed on three-dimensional (3-D) seismic data from James River, Alberta. The structure has an outer diameter of 4.8 km and a raised central uplift surrounded by a rim synform. The central uplift has a diameter of 2.4 km and its crest appears to be uplifted about 400 m above regional levels. The structure is at a depth of about 4500 m. This is below the zone of economic interest and the feature has not been penetrated by any wells. The disturbed sediments are interpreted to be Cambrian. We infer that the structure was formed in Late Cambrian to Middle Devonian time and suffered erosion before the deposition of the overlying Middle Devonian carbonates. Rim faults, probably caused by slumping of material into the depression, are observed on the outside limb of the synform. Reverse faults are evident underneath the feature and the central uplift appears to have coherent internal reflections. The amount of uplift decreases with increasing depth in the section. The entire feature is interpreted to be a cryptoexplosion structure, possibly caused by a meteorite impact. INTRODUCTION Several enigmatic circular structures, of different sizes and ages, have been observed on seismic data from the Western Canadian sedimentary basin (WCSB) (e.g., Sawatzky, 1976; Isaac and Stewart, 1993) and other parts of Canada (Scott and Hajnal, 1988; Jansa et al., 1989). The structures present startling interruptions in otherwise planar seismic features. -

Cross-References ASTEROID IMPACT Definition and Introduction History of Impact Cratering Studies

18 ASTEROID IMPACT Tedesco, E. F., Noah, P. V., Noah, M., and Price, S. D., 2002. The identification and confirmation of impact structures on supplemental IRAS minor planet survey. The Astronomical Earth were developed: (a) crater morphology, (b) geo- 123 – Journal, , 1056 1085. physical anomalies, (c) evidence for shock metamor- Tholen, D. J., and Barucci, M. A., 1989. Asteroid taxonomy. In Binzel, R. P., Gehrels, T., and Matthews, M. S. (eds.), phism, and (d) the presence of meteorites or geochemical Asteroids II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 298–315. evidence for traces of the meteoritic projectile – of which Yeomans, D., and Baalke, R., 2009. Near Earth Object Program. only (c) and (d) can provide confirming evidence. Remote Available from World Wide Web: http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/ sensing, including morphological observations, as well programs. as geophysical studies, cannot provide confirming evi- dence – which requires the study of actual rock samples. Cross-references Impacts influenced the geological and biological evolu- tion of our own planet; the best known example is the link Albedo between the 200-km-diameter Chicxulub impact structure Asteroid Impact Asteroid Impact Mitigation in Mexico and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Under- Asteroid Impact Prediction standing impact structures, their formation processes, Torino Scale and their consequences should be of interest not only to Earth and planetary scientists, but also to society in general. ASTEROID IMPACT History of impact cratering studies In the geological sciences, it has only recently been recog- Christian Koeberl nized how important the process of impact cratering is on Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria a planetary scale. -

The Puzzle of the Missing Large Craters. S

47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2016) 1281.pdf CRATERING ON CERES: THE PUZZLE OF THE MISSING LARGE CRATERS. S. Marchi1, D. P. O'Brien2, P. Schenk3, R. Fu4, A. Ermakov5, M. C. De Sanctis6, E. Ammannito7, D. A. Williams8, S. C. Mest2, C. A. Raymond9, C. T. Russell7; 1Southwest Research Institute ([email protected]), Boulder, CO; 2Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ; 3Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX; 4Lamont-Doherty Earth Ob- servatory, Palisades, NY; 5Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA; 6Istituto Nazionale d'Astrofisica, Rome, Italy; 7University of California, Los Angeles, CA; 8Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ; 9JPL, Caltech, Pasadena, CA. Introduction: Data acquired by the Dawn space- hemisphere, although heavily craters terrains are also craft revealed a portrait of Ceres's surface that, in many found at low latitudes. This observation tells us that to- ways, challenges our preconceived expectations. pographic relaxation due to the presence of an ice-rich Ceres is the largest object in the main belt of aster- shell has to be limited. Furthermore, an improved oids. As such, extensive ground-based and Hubble model of topographic relaxation has constrained the Space Telescope observations have provided a wealth fraction of ice to be <30% in the outer shell [9]. of information [e.g. 1,2] Ceres' surface has a very low A second major finding is the lack of larger craters. albedo (~9 %) [2], while the lack of significant absorp- The largest well recognizable craters are 260-280 km tions bands at visible and near-infrared wavelengths in diameter. Although large scale topography relaxes points toward a more pristine composition [e.g., 3,4] if faster than at small scales, the lack of large craters compared to many siblings in the asteroid belt (and no- seems at odds with the presence of heavily cratered ter- tably to the large asteroid Vesta). -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

POSTER SESSION I: CERES: MISSION RESULTS from DAWN 6:00 P.M

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) sess312.pdf Tuesday, March 21, 2017 [T312] POSTER SESSION I: CERES: MISSION RESULTS FROM DAWN 6: 00 p.m. Town Center Exhibit Area Russell C. T. Raymond C. A. De Sanctis M. C. Nathues A. Prettyman T. H. et al. POSTER LOCATION #171 Dawn at Ceres: What We Have Learned [#1269] A summary of the major discoveries and their implications at the close of the exploration of Ceres by Dawn. Ermakov A. I. Park R. S. Zuber M. T. Smith D. E. Fu R. R. et al. POSTER LOCATION #172 Regional Analysis of Ceres’ Gravity Anomalies [#1374] Put in geological and geomorphological context, the regional gravity anomalies give clues on the structure and evolution of Ceres’ crust. Nathues A. Platz T. Thangjam G. Hoffmann M. Mengel K. et al. POSTER LOCATION #173 Evolution of Occator Crater on (1) Ceres [#1385] We present recent results on the origin and evolution of the bright spots (Cerealia and Vinalia Faculae) at crater Occator on (1) Ceres. Buczkowski D. L. Scully J. E. C. Schenk P. M. Ruesch O. von der Gathen I. et al. POSTER LOCATION #174 Tectonic Analysis of Fracturing Associated with Occator Crater [#1488] The floor, walls, and ejecta of Occator Crater on Ceres are cut by multiple sets of linear and concentric fractures. We explore possible formation mechanisms. Pasckert J. H. Hiesinger H. Raymond C. A. Russell C. POSTER LOCATION #175 Degradation and Ejecta Mobility of Impact Craters on Ceres [#1377] We investigated the degradation and ejecta mobility of craters on Ceres, to investigate latitudinal variations, and to compare it with other planetary bodies. -

50 Years of Petrology

spe500-01 1st pgs page 1 The Geological Society of America 18888 201320 Special Paper 500 2013 CELEBRATING ADVANCES IN GEOSCIENCE Plates, planets, and phase changes: 50 years of petrology David Walker* Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, USA ABSTRACT Three advances of the previous half-century fundamentally altered petrology, along with the rest of the Earth sciences. Planetary exploration, plate tectonics, and a plethora of new tools all changed the way we understand, and the way we explore, our natural world. And yet the same large questions in petrology remain the same large questions. We now have more information and understanding, but we still wish to know the following. How do we account for the variety of rock types that are found? What does the variety and distribution of these materials in time and space tell us? Have there been secular changes to these patterns, and are there future implications? This review examines these bigger questions in the context of our new understand- ings and suggests the extent to which these questions have been answered. We now do know how the early evolution of planets can proceed from examples other than Earth, how the broad rock cycle of the present plate tectonic regime of Earth works, how the lithosphere atmosphere hydrosphere and biosphere have some connections to each other, and how our resources depend on all these things. We have learned that small planets, whose early histories have not been erased, go through a wholesale igneous processing essentially coeval with their formation. -

Impact Cratering

6 Impact cratering The dominant surface features of the Moon are approximately circular depressions, which may be designated by the general term craters … Solution of the origin of the lunar craters is fundamental to the unravel- ing of the history of the Moon and may shed much light on the history of the terrestrial planets as well. E. M. Shoemaker (1962) Impact craters are the dominant landform on the surface of the Moon, Mercury, and many satellites of the giant planets in the outer Solar System. The southern hemisphere of Mars is heavily affected by impact cratering. From a planetary perspective, the rarity or absence of impact craters on a planet’s surface is the exceptional state, one that needs further explanation, such as on the Earth, Io, or Europa. The process of impact cratering has touched every aspect of planetary evolution, from planetary accretion out of dust or planetesimals, to the course of biological evolution. The importance of impact cratering has been recognized only recently. E. M. Shoemaker (1928–1997), a geologist, was one of the irst to recognize the importance of this process and a major contributor to its elucidation. A few older geologists still resist the notion that important changes in the Earth’s structure and history are the consequences of extraterres- trial impact events. The decades of lunar and planetary exploration since 1970 have, how- ever, brought a new perspective into view, one in which it is clear that high-velocity impacts have, at one time or another, affected nearly every atom that is part of our planetary system. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 17, Number 15, April 6, 1990

LAROUCHE So, You Wish to Leant All About BUT YOU'D BEDER EconoInics? KNOW WHAT H. Jr. HE HAS TO SAY by Lyndon LaRouche, A text on elementary mathematical economics, by the world's leading economist. Find out why EIR was right, when everyone else was wrong. The Power of Order from: Ben Franklin Booksellers, Inc. Reason: 1988 27 South King Street Leesburg, Va. 22075 An Autobiography by Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. $9.95 plus shipping ($1.50 for first book, $.50 for each additional book). Information on bulk rates and videotape Published by Executive Intelligence Review Order from Ben Franklin Booksellers, 27 South King St., Leesburg, VA 22075. available on request. $10 plus shipping ($1.50 for first copy, .50 for each ad,:::ional). Bulk rates available. THE POWER OF REASON 1iM.'" An exciting new videotape is now available on the life and work of Lyndon LaRouche, political leader and scientist, who is currently an American political prisoner, together with six of his leading associates. This tape includes clips of some of LaRouche's most important, historic speeches, on economics, history, culture, science, AIDS, and t e drug trade. , This tape will recruit your friends to the fight forr Western civilization! Order it today! $100.00 Checks or money orders should be sent to: P.O. Box 535, Leesburg, VA 22075 HumanPlease specify Rights whether Fund you wish Beta or VHS. Allow 4 weeks for delivery. Founder and Contributing Editor: From the Editor Lyndon H. LaRouche. Jr. Editor: Nora Hamerman Managing Editors: John Sigerson, Susan Welsh Assistant Managing Editor: Ronald Kokinda Editorial Board: Warren Hamerman. -

Hvilke Faktorer Driver Kursutviklingen På Oslo Børs? Av

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Næs, Randi; Skjeltorp, Johannes A.; Ødegaard, Bernt Arne Working Paper Hvilke faktorer driver kursutviklingen på Oslo Børs? Working Paper, No. 2007/8 Provided in Cooperation with: Norges Bank, Oslo Suggested Citation: Næs, Randi; Skjeltorp, Johannes A.; Ødegaard, Bernt Arne (2007) : Hvilke faktorer driver kursutviklingen på Oslo Børs?, Working Paper, No. 2007/8, ISBN 978-82-7553-403-1, Norges Bank, Oslo, http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2498266 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209884 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.no www.econstor.eu ANO 2007/8 Oslo 12. -

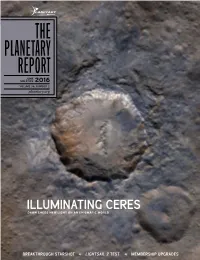

THE PLANETARY REPORT JUNE SOLSTICE 2016 VOLUME 36, NUMBER 2 Planetary.Org

THE PLANETARY REPORT JUNE SOLSTICE 2016 VOLUME 36, NUMBER 2 planetary.org ILLUMINATING CERES DAWN SHEDS NEW LIGHT ON AN ENIGMATIC WORLD BREAKTHROUGH STARSHOT C LIGHTSAIL 2 TEST C MEMBERSHIP UPGRADES SNAPSHOTS FROM SPACE EMILY STEWART LAKDAWALLA blogs at planetary.org/blog. Black Sands of Mars ON SOL 1192 (December 13, 2015), Curiosity approached the side of Namib, a Faccin and Marco Bonora Image: NASA/JPL/MSSS/Elisabetta massive barchan sand dune. Namib belongs to a field of currently active dark basaltic sand dunes that form a long barrier between the rover and the tantalizing rocks of Mount Sharp. This view, processed by Elisabetta Bonora and Marco Faccin, features wind-carved yardangs (crests or ridges ) of Mount Sharp in the background. After taking this set of photos, Curiosity went on to sample sand from the dune, and it is now working its way through a gap in the dune field on the way to the mountain. —Emily Stewart Lakdawalla SEE MORE AMATEUR-PROCESSED SPACE IMAGES planetary.org/amateur SEE MORE EVERY DAY! planetary.org/blogs 2 THE PLANETARY REPORT C JUNE SOLSTICE 2016 CONTENTS JUNE SOLSTICE 2016 COVER STORY Unveiling Ceres 6 Simone Marchi on why Ceres is a scientific treasure chest for Dawn. Pathway to the Stars Looking back at years of Society-led solar sail 10 development as Breakthrough Starshot is announced. Life, the Universe, and Everything 13 Planetary Radio in Death Valley. ADVOCATING FOR SPACE Partisan Peril 18 Casey Dreier looks at the U.S. President’s impact on space policy and legislation. DEVELOPMENTS IN SPACE SCIENCE Update on LightSail 2 20 Bruce Betts details the progress we’ve made in the year since LightSail 1 launched. -

3D Seismic Expression of a Cryptoexplosion Structure

CANADUN JOURNAL OF EXPLORATION GEOPH”SICS “OLD 29. Pm 2 ,tECEMBER 19931, P 429~439 3-D SEISMIC EXPRESSION OF A CRYPTOEXPLOSION STRUCTURE’ J. HELEN ISAAC~AND ROEERTR. SSEWART~ Mclosh, 1989: Sharpton and Ward, 1990). Impact craters can AWTRACT he termed either simple or complex, the main difference being the presence of multiple ring structures and central An enigmaticcircular itr”Ct”ce is observedon three-*immsionai uplift in a complex crater. The morphological change takes (3-D, ,eimlic d&mfrom Jilmcs River. Alberta It hasan uuter diammr uf 4.8 km anda raisedcentral uplift mrruundrdby a ring ,ynform. place at an excavation cavity diameter of ahout 2 km in sedi- The Centraluplift hasB diameter“1 2.4 km and if6 crestappears to mentary rocks and 4 km in crystalline rocks (Dence. 1972). he aho”, 400 m abovercgkml levels.The top of ihe StmClllr~ii ill B The principal feature of a complex impact crater is a central depth“f aho”, 4500,” and is belowtile LOW“f previousrc”n”“lic interest.Consequently. the featurehas ll”L beenpcnctrated by any peak, or group of peaks. surrounded by a llat tloor inside a wc,,s in the surveyarea. me seismic&lra inteqmation indicatr, terraced rim (Dencr, 1965). Complex crater central peaks are that the dimrbed scdimmtrare Cambrian in age.tt ii cstimilledIhat composed of def(mned and fractured rocks which arc uftcn the structure was formed during the Late CambrianIu Middle older than the country rock surrounding the structure. Partial Devonianlime petid andsuffered SeYcre W”bi,,” Mrw ,llCdrpositim “1 ,hCwcrlying Middle andUpper “ev”“ian carbonares.Rim fml,5, collapse of the central peak may he the source of some of the prohahiycaused by slumpingOf mmria, iill the dqmsion.