Understanding Recent Changes in Household Formation Rates and Their Implication for Planning for Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE OVERHEATED ARC - a Critical Analysis of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford-Newbury “Growth Corridor”

THE OVERHEATED ARC - A Critical Analysis of the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford-Newbury “Growth Corridor” Part 1 A report by Smart Growth UK FEBRUARY 2019 http://www.smartgrowthuk.org 0 Contents __________________________________________________________________________ Executive summary 3 1. Introduction 7 2. What they propose 10 3. The damage it would do 16 4. Transport implications 23 5. The evolution of a bad idea 30 6. An idea founded on sand 54 7. Conclusions 63 1 “The Brain Belt” [Stella Stafford] 2 Executive Summary __________________________________________________________________________ Introduction The so-called “Brain Belt” has been evolved by a small and unrepresentative clique in Whitehall and beyond, virtually without consultation. There has been little or no consideration of the huge environmental damage it would do or the loss of food production involved. Misleading claims have been made about it having the highest productivity or it being the centre of the knowledge economy yet no-one apparently has asked whether, if the Arc concept is a sound one, there are other places in the UK it could be applied more productively and less damagingly. What they propose The Arc has grown since its inception from the “blob on a map” proposed by the National Infrastructure Commission to five whole counties plus Peterborough and the ill-defined M4 and M11 corridors. The NIC grew from a plan to link Oxford and Cambridge by motorway, via the NIC’s plans for new settlements and a million sprawl homes, to the Government’s plan to turn England’s bread and vegetable basket into “a world-leading economic place”. A new motorway from Cambridge to Newbury is at the centre of the plan which also claims the long-hoped-for Oxford-Cambridge railway reopening as its own idea. -

Housing in the South East

House of Commons South East Regional Committee Housing in the South East First Report of Session 2009–10 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30 March 2010 HC 403 Published on 7 April 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £22.00 The South East Regional Committee The South East Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine regional strategies and the work of regional bodies. Current membership Dr Stephen Ladyman MP (Labour, South Thanet) (Chairman) Ms Celia Barlow MP (Labour, Hove) David Lepper MP (Labour, Brighton, Pavilion) Gwyn Prosser MP (Labour, Dover) Mr Andrew Smith MP (Labour, Oxford East) Powers The committee is one of the Regional Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/se.cfm. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Sîan Woodward (Clerk), Duma Langton (Inquiry Manager), Leena Mathew (NAO Adviser), Emma Sawyer (Senior Committee Assistant), Ian Blair (Committee Assistant), and Anna Browning (Committee Assistant). Contacts All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the South East Committee, House of Commons, 7 Millbank, -

Intro to Ntch10

The London New Towns in their changing regional context Tony Champion, Emeritus Professor of Population Geography, Newcastle University Abstract As the 75th anniversary of the British New Towns programme approaches, this chapter assesses the contribution that London New Towns have made to accommodating population growth in south-east England and examines the extent to which the original New Town principles have left a distinctive legacy in terms of social composition and self-containment. According to the evidence presented in this chapter, the London New Towns have tended to become less distinctive compared to their regional context, but at the same time they retain elements of the features that marked them out as different 40 years ago. Keywords: London New Towns; Population growth; Social balance; Self- containment; Regional comparison. Introduction As the 75th anniversary of the British New Towns programme approaches, there is renewed interest in this approach to accommodating population growth in south-east England where for many years the rate of house-building has been lagging behind projected housing need. The first London – and British – New Town, Stevenage, was designated in November 1946, just a few months after parliamentary approval had been given to the New Towns Act following the recommendations of the Reith Committee (Ministry of Town & Country Planning, 1946). Over the next three years, 1 seven more designations were made for accommodating households and businesses from London: in chronological order, Crawley, Hemel Hempstead, Harlow, Hatfield, Welwyn Garden City, Basildon and Bracknell (this in June 1949). Nearly two decades then elapsed before a further two designations were made to cater for renewed regional population growth in what is now referred to as the Wider South East (WSE) comprising the South East and East of England regions – Milton Keynes and Peterborough in 1967 – followed in 1968 by Northampton which is located over the border in the East Midlands region. -

From Homes for Heroes to Today

From Homes for Heroes to today ...a brief history of housing in London “Home for Heroes” is among the most famous promises ever made by a British Prime Minister and one that had a profound impact on the nation’s housing, nowhere more so than in London. Nearly one hundred years on though and the capital still faces an uphill battle to provide decent housing for its growing population It is unlikely that the assassin Gavrilo Princip had UK housing policy much in mind when he stepped towards the car carrying Archduke Ferdinand of Austria; but the bullet he fired on 28 June 1914 was to have a profound impact on our nation’s housing that is still felt to this day. As a prime cause of the First World War, the assas- sination of the Archduke was responsible for the mass mobilisation of recruits. And it was British army chiefs’ alarm at the poor health of those recruits led directly to the creation of what we now know as council housing in the UK. The queues of young men signing up to join the war had provided the government with a startling insight into the impact of poor housing on the nation’s workers and, once the war was won, Prime Minister Lloyd George famously promised to pro- vide them with ‘Homes fit for Heroes’. The Housing Act of 1919, known as the Addison Act association press after its author, the Minster for Health Dr Chris- topher Addison, pledged substantial government subsidies to build half a million new homes within three years. -

Issue 81 Spring 2020

The Oxon Recorder Issue 81 Spring 2020 T H E S O P X R O I N N G R E 2 C 0 O 2 R 0 D E R Contents: • OBR News • The making of a field archaeologist: Part 1 • Probate evidence of 17c building alterations • Forthcoming events • AGM information 1 © Oxfordshire Buildings Record 2020 The Oxon Recorder Issue 81 Spring 2020 The Oxon Recorder is the newsletter of Oxfordshire Buildings Record and is published four times a year. OBR aims to advance education and promote research on the buildings of Oxfordshire by encouraging the recording of buildings and to create and manage a publicly accessible repository of records relating to such buildings. The Oxon Recorder is also available in the members’ section of our website: www.obr.org.uk Next copy date for contributions is 1 June. Please send any contributions or comments to Richard Farrant at [email protected] Contributions need to be Word or Pages documents with accompanying photographs sent separately in high resolution jpg format. OBR News ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING. As you will know from the Secretary’s circular of 20 March, the AGM scheduled for 16 May is deferred indefinitely due to the Coronavirus lock- down. The documents for presentation to the AGM are annexed to this newsletter, namely the Secretary’s and Treasurer’s reports and the independently examined annual accounts. All committee members and officers will remain in post until a General Meeting can be convened. It will be assumed members are content to adopt the accounts and the reports, and also for the committee members and officers to remain in post, unless objections are sent to the Secretary by 16 May. -

Financial Reconstruction of New Towns in England

Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Department of the Environment: Financial Reconstruction of New Towns in England Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30 April 1987 Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London ~E5.70net 339 This report is presented to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the National Audit Act, 1983. Gordon Downey Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 29 April 1987 Contents Department of the Environment: Financial Reconstruction of New Towns in England Pages Report l-11 Introduction EstablishmentofNewTownbodies Financial objectives and outturn Causes of financial difficulties Financialreconstruction New financial control regime NAOaccesstoNewTownbodies Summary of NAO findings and conclusions Glossary of abbreviations and terms 12 Appendix Objectives ofthe New Towns 13 Table 1: Status of New Towns at December 1986 Date of transfer designation to Commission 1st Generation Stevenage 1946 1960 Crawley 1947 1962 Harlow 1947 1960 Hemel Hempstead 1947 1962 Hatfield 1946 1966 Welwyn Garden City 1946 1966 Basildon 1949 1966 Bracknell 1949 1962 Corby 1950 1960 2nd Generation Skelmersdale 1961 1965 Redditch 1964 1965 3rd Generation Northampton 1966 1965 Central Lancashire 1970 1965 Date of Tareet Yap designation dissolution date 1st Generation Aycliffe & Peterlee’ 1947 & 1946 1966 2nd/3rd Generations Washington 1964 1966 Milton Keynes 1967 1992 Peterborough 1967 1966 Telford 1966 1991 Warrington & Runcorn 1966 & 1964 1969 Notes: 1. Aycliffe & Peterlee Development Corporations were merged in 1965. 2. Warrington & Runcorn Development Corporations were merged in 1961. Department of the Environment: Financial Reconstruction of New Towns in England Report 1. In 1966 the Department of the Environment (DOE) revised the financial structure of the New Town Development Corporations and the Commission for the New Towns in England. -

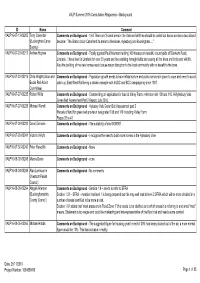

VALP Summer 2016 Consultation Responses – Background

VALP Summer 2016 Consultation Responses – Background ID Name Comment VALP16-07-13-00205 Terry Cavender Comments on Background - 1.64 There are 3 canal arms in the Vale and all three should be called out hence sentence two should (Buckingham Canal become: "The Grand Union Canal and its arms to Wendover, Aylesbury and Buckingham....." Society) VALP16-07-22-00212 Andrea Hughes Comments on Background - Totally against Paul Newman building 300 houses on beautiful countryside off Derwent Road, Linslade. I have lived in Linslade for over 33 years and love walking through fields and seeing all the trees and birds and wildlife. Also the building of the new homes would cause major disruption to the local community with no benefit to the town. VALP16-07-22-00219 Chris Wright (Oxon and Comments on Background - Population growth needs to have infrastructure and public services in place to cope and need to avoid Bucks Rail Action catch up. East West Rail being a classic example with AVDC and BCC campaigning since 1987. Committee) VALP16-07-27-00225 Robert Willis Comments on Background - Commenting on application for land at Valley Farm, reference site 109 and 110, Aylesbury Vale Green Belt Assessment Part 2 Report, July 2016. VALP16-07-27-00226 Michael Wendt Comments on Background - Aylesbry Vale Green Belt Assessment part 2 Parcels of land for green belt provision designated 109 and 110 including Valley Farm Pages 38 to 41 VALP16-07-28-00233 David Ginnane Comments on Background - The suitability of site WGR001 VALP16-07-29-00241 Victoria Wright Comments on Background - I recognise the need to build more homes in the Aylesbury Vale. -

London and WSE: the Case for a City-Regional Perspective Discussion Paper for London & SE Research Network Meeting, 9 July 2018

London and WSE: the case for a city-regional perspective Discussion paper for London & SE research network meeting, 9 July 2018 This note focuses on the evidence needed to assist strategic planning in London and the Wider South East. Given the political resistance to any type of formal regional governance, advocating the need for a clearer contextual understanding of how the city region currently functions, might be more realistic than any hint of a regional plan. Any new insights and/or examples of missed opportunities might act as a catalyst to approach things more strategically. Regional collaboration in the past Strategic planning goes in and out of fashion. But it is the case that in its absence, local planning decisions tend to live "off the fat” of previous strategic development frameworks. Hence during the Thatcher years of the 1980s, the local authority mindset was still geared towards focusing growth in the areas identified in the Strategic Plan for the South East (SPSE) 1971 (Reading, Crawley, Southampton). The regional planning era in the 2000s gave these ideas a refresh, e.g. with recommendations for strategic Green Belt releases north of Harlow, west of Stevenage and north Guildford which continue to be taken forward in the localist era. The Thames Gateway has remained a long-established growth valve through various political cycles. The organisational means by which evidence was assembled and logical decisions taken has varied over the years: • For the SPSE 1971 it was spearheaded by the SE Economic Planning Council (expert appointees), but also including government experts and the Standing Conference of local authorities. -

The Urban Planning of Milton Keynes

1 | the Milton Keynes travel guide the New Town travel guides MILTONnowa KEYNEShuta internationalINTERNATIONAL NEW New TOWN Town INSTITUTEinstitute 2 | the Milton Keynes travel guide 1 | the Milton Keynes travel guide the New Town travel guides Milton Keynes INTI - International New Town Institute 2 | the Milton Keynes travel guide 3 | the Milton Keynes travel guide Colofon Content The New Town travel guides are part of a series issued by the International New Town Institute (INTI). 4 Chapter 1: The Story of Milton Keynes Authors: all participants of the lecture course 2013: Marjolein Overtoom, Jordi van Seventer, Tura Cousins-Wilson, Kevin Hutchinson, Danbi Lee, Roman Popadyuk, Max Fabris, Teun Bimbergen, Julia van der Meer, Yongki Kim, Efthymios Mavrikas, Anne Schaap. 2014 Groep 1 - History: Martin Bakermans, Lisanne Caspers, Jeremie Martin Peterson, Agnes Galama, 14 Chapter 2: Johanna Wilhelmus Stuijt, Bram Klatser. Groep 2 – Urbanism: Ksenia Polyanina, E. Andrusenko, The Urban Planning of Anne van Stijn, Esra Esen, M. Tuangthong, Chiyu Li. Groep 3 – Architecture: Janneke van der Leer, Martín Fernández de Córdova, Simone Costa, Klaas Sijmen Akkerman, E. Balzarini. Groep 4 – Use & Milton Keynes Attractions: Agate Kalnpure, Maurice Pascal Giliams, Pui Yi Kong, H.J.M. Keizer, Daniëlle Gunnewijk, Dion Mengerink, Lowin van der Burg. 44 Chapter 3: Staff: INTI / TU Delft, Design as Politics Evolving Architecture in Mike Emmerik, Michelle Provoost, Wouter Vanstiphout, Lena Knappers a British New Town Editor: Sophie Rijnaard Graphic design: Ewout Dorman, Gerard Hadders 84 Chapter 4: Publisher: Use & Attractions in the International New Town Institute (INTI) New Town Most of the images used in the publication are developed by the authors or taken by the students during the excursion to Milton Keynes in 2013 and 2014 unless stated otherwise. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A social geography of urban fringe housing estates Blowers, A. T. How to cite: Blowers, A. T. (1970) A social geography of urban fringe housing estates, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9682/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk A.T. BLOWERS A SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY OF URBAN FRINGE HOUSING ESTATES M.Litt Thesis 1970 ABSTRACT A SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY OF URBAN FRINGE HOUSING SSTAT_ES The thesis explores three themes for each of which hypotheses are put forward based, upon existing research. They are; first, that there are recognisable socio-geographic subdivisions within any community of neighbourhood unit size; second, that design and layout are important determinants of the social pattern; and third, that attitudes to place are the product of environmental as well as individual characteristics. -

Milton Keynes and the Liquid Landscape, 1967-1978

UHPH_14: Landscapes and ecologies of urban and planning history | 603 Milton Keynes and the Liquid Landscape, 1967-1978 Lauren Pikó University of Melbourne [email protected] Language describing urban planning is often reliant on organic imagery, from the 'flow' of traffic, bodily metaphors of cohesion and health, to the 'monstrosity' of unwanted or questionable urban developments. This paper explores metaphors of liquidity, flow and submergence, as used to express ideas of 'good' and 'bad' urban environments in debates around the growth of the large-scale, low-density, explicitly post-industrial planned city of Milton Keynes. Developed in the context of the postwar language of 'overspill', Milton Keynes' reception in print and popular culture suggests tendencies to understand urban landscapes as receptacles for an inert population which would adopt any containing shape imposed by the urban structure. Unlike many earlier planned developments in postwar Britain, Milton Keynes' plan was intended as less an imposition of form on its future inhabitants, than a flexible structure which would facilitate greater agency on individual, community and market-force levels. Through examining the tension between flow and containment, responses to Milton Keynes' early development suggest some preconceptions regarding the role of cities in determining the industrial and social form of its inhabitants' lives, while planned cities proposing to embrace rather than to restrict flow are viewed with suspicion. Over the course of the 1970s, the tone of this language shifted, becoming increasingly fearful of deterministic space and viewing the containment provided by Milton Keynes as a social evil rather than a positive construct protecting the British landscape. -

Lessons from the British and French New Towns: Paradise Lost?

Lessons from the British and French New Towns This page intentionally left blank Lessons from the British and French New Towns: Paradise Lost? EDITED BY DAVID FÉE University of Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3, France SABINE COADY SCHÄBITZ Coventry University, UK BOB COLENUTT Oxford Brookes University, UK United Kingdom – North America – Japan – India – Malaysia – China Emerald Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2021 Copyright © 2021 Emerald Publishing Limited Reprints and permissions service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters’ suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-83909-431-6 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-83909-430-9 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-83909-432-3 (Epub) Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables ix About the Contributors xi Acknowledgements