Sustainability in the Workplace 1 Sustainability: a Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Thesis Master's Programme in Industrial Management and Innovation, 120 Credits

Master Thesis Master's Programme in Industrial Management and Innovation, 120 credits Capturing Business Model Innovation Driven by the Emergence of New Technologies in Established Firms A Case Study at Siemens Healthineers Thesis in Industrial Innovation Management, 30 credits Halmstad 2018-06-16 Emma Bäckman, Josefin Ellmarker HALMSTAD UNIVERSITY Abstract Background: It is argued that the emergence of new technologies and the digitalization can improve the healthcare, make it more efficient, personalized and available for everyone. The healthcare has already begun to become more digitized and there is no doubt that this trend will continue. Moreover, it is argued that AI will have a major impact on the MedTech and healthcare industry. Problem discussion: To stay competitive it has been concluded that firms must update and rethink their business models constantly thus, to undertake business model innovation. This applies specially to established firms that have been successful with the same business model for a long time. Despite the fact that the existing literature addresses the importance of business model innovation, very little attention has been drawn to how to actually achieve this change. Purpose: The purpose of this study is to explore how business models in established firms within the MedTech industry develops over time due to the emergence of new technologies. More specifically, we focus on how artificial intelligence is influencing and will influence the business models in the MedTech industry. Methodology: This study has been performed through a single case study at Siemens Healthineers. The primary data has been gathered through four meetings with people with expertise in the field of artificial intelligence as well as the MedTech and healthcare industry. -

Medical Additive Manufacturing/ 3D Printing Annual Report 2018 Improving Public Health

Medical Additive Manufacturing/ 3D Printing Annual Report 2018 Improving Public Health Each year, healthcare needs and costs grow due to an aging population, the rise in chronic diseases, and more. In fact, global healthcare spending is projected to reach nearly $9 trillion by 20201. To address this, practitioners in the healthcare industry continue to look for innovations that can provide quality care to patients at a reasonable cost. But they can’t do it alone. Today, the manufacturing industry is an important partner, with one particularly bright opportunity focused on Medical Additive Manufacturing/3D Printing (AM3DP). From anatomical models to early bioprinting applications, the use of AM3DP is providing benefits for patients and physicians/institutions including: ■ Better patient outcomes ■ Less time in the operating room ■ Reduced costs In 2017, as outlined in this Annual Report, collaboration between hospitals, device manufacturers, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and partners such as SME, led to extraordinary strides in identifying industry trends, opportunities, challenges and solutions. These partnerships drive efficiency through best practice sharing as well as accelerate innovation for applications such as bioprinting and tissue fabrication. They also lay the groundwork for 3D printing of organs and scaling up production of tissues which are still decades away. With millions of patients already directly impacted by the technology, this momentum continues into 2018 and beyond where AM3DP will continue to positively impact public health and drive strong business results. This 2017 Annual Report covers: COVER: Justin Ryan holds a pediatric heart model 3D-printed at the ■ Industry Overview Phoenix Children’s Hospital Cardiac 3D Print Lab. -

Healthcare & Life Sciences Group

HEALTHCARE & LIFE SCIENCES GROUP 2 1 Healthcare and life sciences clients have long turned to S&C for help succeeding in today’s rapidly changing business environment. Large and mid-size, public and private, throughout their lifecycles, these companies rely on our multi-disciplinary, global team to address their most complex legal and business challenges and reach their strategic goals. Sector expertise: We offer unrivaled OUR CLIENTS GET… knowledge of the healthcare and life sciences industries, our clients’ businesses and the sector-specific competitive pressures bearing down on them. Sullivan & Cromwell’s Healthcare and Life Sciences Group has negotiated complex transactions and resolved high-stakes disputes for almost three decades. Today, it possesses an unparalleled grasp of these sectors and a practical understanding of the commercial realities underlying them. We position our clients to succeed through it all. The Firm represents international clients in the following healthcare sectors: Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences Medtech Health Insurers Healthcare Services 2 Legal expertise: Clients come to us An integrated, global team: for the high-quality counsel and hands-on We’re a core group of dedicated healthcare representation we offer across multiple advisers across our 13 offices on four legal specialties, to successfully execute continents with a strong track record of their most important deals and resolve the sector’s most significant transactions critical disputes. We can execute any type and litigation matters, supported by all of transaction in any economic climate or the resources of an integrated, global firm. geographic region. Our experience in this We’re grateful to our clients for trusting sector includes: us with their future, and we’ll continue to help them position themselves for growth M&A and success in this exciting and ever- Corporate finance changing industry. -

Conference Programme Speakers Overview

CONFERENCE BOOK Celebrating 60 years of the benefits of innovation in medical technology to Society CONFERENCE PROGRAMME & SPEAKERS OVERVIEW 13 & 14 NOVEMBER 2019 COCIR, the European Coordination Committee of the Radiological, Electromedical and Healthcare IT Industry European Coordination Committee of the Radiological, Electromedical and Healthcare IT Industry PROGRAM WEDNESDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2019 17:30 REGISTRATION & WELCOME Drinks, Photographs 18:30 ANNIVERSARY CEREMONY OPENING BY COCIR PRESIDENT Jan KIMPEN / COCIR President and Chief Medical Officer at Royal Philips KEYNOTE SPEECHES BY EUROPEAN COMMISSION Manuel MATEO GOYET / Member of the Cabinet of Commissioner Gabriel, the Digital Economy and Society portfolio at the European Commission Andrzej RYS / Director Health Systems, Medical Products & Innovation at DG Santé, European Commission HEALTHCARE FUTUROLOGIST: “WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?” Koen KAS / Healthcare futurist, entrepreneur, professor of molecular oncology, and renowned international keynote speaker. 19:30 GALA DINNER Museum visit (optional) & Networking 2 COCIR 60 YEARS ANNIVERSARY COCIR PROGRAM PROGRAM THURSDAY 14 NOVEMBER 2019 08:30 REGISTRATION & WELCOME / Coffee 09:00 WELCOME by Nicole DENJOY / COCIR Secretary General Moderation by Maryline FIASCHI / Managing Director, Science Business 09:15 KEYNOTE SPEECH BY FINNISH PRESIDENCY Tuula HELANDER / Senior Advisor, Cabinet and Strategy Group of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Health Secretary General, Finnish Cancer Institute 09:30 SESSION -

Common Stocks — 104.5%

Eaton Vance Tax-Advantaged Global Dividend Income Fund January 31, 2021 PORTFOLIO OF INVESTMENTS (Unaudited) Common Stocks — 104.5% Security Shares Value Aerospace & Defense — 0.8% Safran S.A.(1) 98,721 $ 12,409,977 $ 12,409,977 Banks — 6.7% Bank of New York Mellon Corp. (The) 518,654 $ 20,657,989 Citigroup, Inc. 301,884 17,506,253 HDFC Bank, Ltd.(1) 512,073 9,775,702 ING Groep NV(1) 1,676,061 14,902,461 Japan Post Bank Co., Ltd. 445,438 3,851,696 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Inc. 2,506,237 11,317,609 Mizuho Financial Group, Inc. 292,522 3,856,120 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, Inc. 186,747 5,801,916 Wells Fargo & Co. 341,979 10,218,332 $ 97,888,078 Beverages — 1.0% Diageo PLC 378,117 $ 15,180,328 $ 15,180,328 Biotechnology — 1.2% CSL, Ltd. 82,845 $ 17,175,550 $ 17,175,550 Building Products — 0.9% Assa Abloy AB, Class B 509,607 $ 12,603,485 $ 12,603,485 Chemicals — 0.7% Sika AG 38,393 $ 10,447,185 $ 10,447,185 Construction & Engineering — 0.0% Abengoa S.A., Class A(1)(2) 311,491 $ 0 Abengoa S.A., Class B(1)(2) 3,220,895 0 $0 Construction Materials — 0.9% CRH PLC 332,889 $ 13,660,033 $ 13,660,033 Consumer Finance — 0.6% Capital One Financial Corp. 79,722 $ 8,311,816 $ 8,311,816 1 Security Shares Value Diversified Financial Services — 2.5% Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., Class B(1) 101,853 $ 23,209,243 ORIX Corp. -

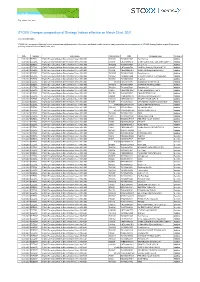

STOXX Changes Composition of Strategy Indices Effective on March 22Nd, 2021

Zug, March 13th, 2021 STOXX Changes composition of Strategy Indices effective on March 22nd, 2021 Dear Sir and Madam, STOXX Ltd., the operator of Qontigo’s index business and a global provider of innovative and tradable index concepts, today announced the new composition of STOXX Strategy Indices as part of the regular quarterly review effective on March 22nd, 2021 Date Symbol Index name Internal Key ISIN Company name Changes 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD TW01UK TW0001722007 Twn Fertilizer Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD CN0010 CNE1000002H1 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD TW02MD TW0002301009 Liteon Tech Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD CN249E CNE000000T59 YANTAI CHANGYU PION.WINE 'B' Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD CN1I6O CNE100000HF9 CHINA MINSHENG BANKING H Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD TW025W TW0002015005 Feng Hsin Iron Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD TW505Z TW0006412000 CHICONY POWER TECHNOLOGY Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD TW0751 TW0004938006 Pegatron Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets Diversification Select 100 USD 691316 HK0270001396 Guangdong Investment Ltd. Addition 12.03.2021 EDEDSL STOXX Emerging Markets -

Siemens Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 siemens.com Table of contents . A B C Combined Management Report Consolidated Financial Statements Additional Information A.1 p 2 B.1 p 62 C.1 p 132 Organization of the Siemens Group Consolidated Statements Responsibility Statement and basis of presentation of Income C.2 p 133 A.2 p 3 B.2 p 63 Independent Auditor ʼs Report Financial performance system Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income C.3 p 139 A.3 p 6 Report of the Supervisory Board Segment information B.3 p 64 Consolidated Statements C.4 p 144 A.4 p 18 of Financial Position Corporate Governance Results of operations B.4 p 65 C.5 p 157 A.5 p 21 Consolidated Statements Notes and forward- looking Net assets position of Cash Flows statements B.5 p 66 A.6 p 22 Financial position Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity A.7 p 26 B.6 p 68 Overall assessment of the economic position Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements A.8 p 28 Report on expected developments and associated material opportunities and risks A.9 p 40 Siemens AG A.10 p 43 Compensation Report A.11 p 57 Takeover-relevant information A. Combined Management Report A.1 Organization of the Siemens Group and basis of pr esentation Siemens is a technology company with core activities in the fields Non-financial matters of the Group of electrification, automation and digitalization and activities and Siemens AG in nearly all countries of the world. We are a leading supplier of Siemens has policies for environmental, employee and social power generation, power transmission and infrastructure solu- matters, for the respect of human rights, and anti-corruption and tions as well as automation, drive and software solutions for in- bribery matters, among others. -

Siemens Healthineers · Flyer DIN Long Portrait · Template

Dr. Roland Busch Information on the Supervisory Board candidate proposed for election under Agenda Item 6 2002 Siemens Aktiengesellschaft, Head of Memberships of comparable domestic or Infotainment Solutions Division foreign controlling bodies of commercial enterprises: 2005 Siemens VDO Automotive Asia Pacific Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China • Atos SE, Bezons, France • President and CEO • Arabia Electric Ltd. (Equipment), Jeddah, * 2007 Siemens Aktiengesellschaft, Saudi Arabia Transportation Systems Group, • ESMT European School of Management Erlangen, Germany and Technology GmbH, Berlin, Germany • Head of Mass Transit Division Dr. Roland Busch • ISCOSA Industries and Maintenance Ltd., * 2008 Siemens Aktiengesellschaft, Dammam, Saudi Arabia (deputy chairman) Deputy Chief Executive Officer, Chief Corporate Development Department, • Siemens Ltd., Riyadh, Saudi Arabia* Technology Officer and member of the Munich, Germany Managing Board of Siemens Aktien • Siemens W.L.L., Doha, Qatar* gesellschaft, Berlin and Munich, Germany • Head of Corporate Strategies • VA TECH T&D Co. Ltd., Riyadh, born on November 22, 1964 in Erlangen, 2011 Member of the Managing Board of Saudi Arabia* Siemens Aktiengesellschaft Germany • Chief Technology Officer since Dr. Busch is a member of the Managing December 2016 Education: Board of Siemens Aktiengesellschaft, with its • Chief Operating Officer from registered seat in Berlin and Munich. Siemens October 2018 until September 2019 • Studied physics at Friedrich Alexander since Aktiengesellschaft directly and indirectly University in ErlangenNuremberg, Germany, 2019 • Chairman of the Supervisory Board holds 85% of the Company’s capital stock at and at the University of Grenoble, France of Siemens Mobility GmbH since the time Notice of the Annual Shareholders’ Meeting is given. Pursuant to Section 5.4.1 (6) • Dipl.Phys., Dr. -

Life Sciences Newsletter Q2 2018

KPMG Corporate Finance LLC Healthcare Life Sciences M&AQuarterly Q2 2018 © 2018 KPMG Corporate Finance LLC, a Delaware limited liability company. Member FINRA and SIPC. KPMG Corporate Finance LLC is a subsidiary of KPMG LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership and the U.S. member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. LIFE SCIENCES M&A NEWSLETTER KPMG Corporate Finance LLC Global Life Sciences Sector Coverage(1) U.S. Life Sciences Team Jason Moran Amanda Dydynski Erik Jordan Sandy Prabhakar Managing Director & Head Senior Associate Director & Head of Director & Head of of Healthcare Life Sciences Healthcare Life Sciences Private Equity International Desk San Francisco San Francisco Los Angeles Chicago T: 415-949-8909 T: 415-963-8401 T: 213-955-8722 T: 312-665-1990 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] United Kingdom Germany France Canada Japan Andrew Nicholson Florian Frei Guillaume Cauchoix Neil Blair Toshiaki Ishii Ireland Sweden Spain India China Michele Connolly Christian Terslow Luis Zaragoza Sanjay Singh Andy Qiu Finland Switzerland Italy South Korea Australia Jukka Teikari Patrik Kerler Paulo Mascaretti Sung-Won Park Peter Turner Netherlands Austria Portugal Vietnam New Zealand Danny Bosker Klaus Mittermair João Leal John Ditty Gary Ivory Denmark Belgium Poland Russia Philippines Eric Bots-Bjerre Peter Lauwers Krzysztof Klamut Robert Vartevanian Michael Guarin KPMG Corporate Finance(1) KPMG Corporate Finance provides a broad range of investment banking and strategic advisory services to domestic and international clients and is a leading global middle market investment banking platform — Average 350 transactions annually for the last five years — Over 2,500 investment banking professionals worldwide — Offices in 84 countries with extensive cross-border abilities Notes: (1) Represents the global Corporate Finance practices of KPMG International’s network of independent member firms. -

Company Title 3Form Process Engineer 5K Inc

Company Title 3form Process Engineer 5K Inc. Chief Executove Officer A. O. Smith Corp. Director of Enterprise Excellence A. O. Smith Corp. Enterprise Excellence Supervisor A. O. Smith Corp. Division CI Manager Abbott Nutrition Program Manager, Global Logistics Excellence Above All Event Management Conference Designer Access Laser Company Laser Technician Access Laser Company Quality and Continuous Improvement Manager Access Laser Company Supply Chain Supervisor Accuride Corporation SVP QLMS & EHS ACHIEVE Institute Board Advisor A-dec Inc. Director of Corporate Quality & OpEx A-dec Inc. Director of Supply Chain A-dec Inc. VP Manufacturing ADI 5S Lean Coordinator Aera Energy, LLC Lean Advisor Aera Energy, LLC Process Specialist Aera Energy, LLC Project Manager Aera Energy, LLC Purchasing Specialist Aera Energy, LLC SAP Basis Administrator Aera Energy, LLC Accountant Aera Energy, LLC Geologist Aera Energy, LLC Industrial Engineer Aera Energy, LLC Materials Management Supervisor Aera Energy, LLC Process Analyst Aera Energy, LLC Process Specialist Aera Energy, LLC Process Supervisor Aera Energy, LLC SYSTEMS & CONTROLS MANAGER Aera Energy, LLC Contract Manager Aerco Jr. Manufacturing Engineer Aerco Sr. Production Manager Aerco VP Operations Aerco Jr. Quality Engineer Aflac Director Aflac Vice President AGCO Corporation Continuous Improvement Engineer AGCO Corporation Director, Digital Transformation, Global Manufacturing AGCO Corporation Director, Operations Air Force Process Improvement Manager Airmar Technology Corp. Production Manager Alcon Inc. Associate Director OpEx Alcon Inc. Global Operational Excellence Alcon Inc. Operational Excellence Site Lead Alcon Research Ltd Operations Director Allergan Engineer, Facilities Engineering Allergan Pharmaceutical Technology Engineer III Allergan Sr. Manager Engineering AM General VP Manufacturing Amazon Mechanical Engineer Ameren Sr. Lean CI Engagement Manager Ameren Continuous Improvement Supervisor Amgen Principal Engineer Operations Improvement AML Sentinel Corp CEO Anchor Industries, Inc. -

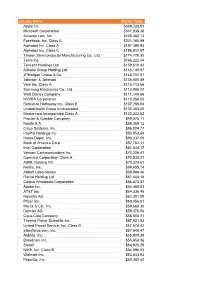

Security Name Market Value Apple Inc. $669,723.81 Microsoft Corporation $541,938.38 Amazon.Com, Inc

Security Name Market Value Apple Inc. $669,723.81 Microsoft Corporation $541,938.38 Amazon.com, Inc. $428,460.13 Facebook, Inc. Class A $201,160.99 Alphabet Inc. Class A $197,390.94 Alphabet Inc. Class C $196,512.97 Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd. $174,778.55 Tesla Inc $166,222.44 Tencent Holdings Ltd. $159,610.32 Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. $146,148.97 JPMorgan Chase & Co. $145,702.81 Johnson & Johnson $135,500.49 Visa Inc. Class A $116,713.66 Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. $113,906.22 Walt Disney Company $111,149.66 NVIDIA Corporation $110,259.00 Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Class B $107,266.84 UnitedHealth Group Incorporated $102,365.05 Mastercard Incorporated Class A $102,242.62 Procter & Gamble Company $99,475.11 Nestle S.A. $98,369.12 Cisco Systems, Inc. $96,024.77 PayPal Holdings Inc $93,953.59 Home Depot, Inc. $90,337.09 Bank of America Corp $87,762.11 Intel Corporation $81,044.17 Verizon Communications Inc. $74,326.41 Comcast Corporation Class A $70,530.31 ASML Holding NV $70,329.61 Netflix, Inc. $69,655.14 Abbott Laboratories $68,944.36 Roche Holding Ltd $67,444.18 Costco Wholesale Corporation $66,473.37 Adobe Inc. $64,468.83 AT&T Inc. $64,336.45 Novartis AG $62,301.00 Pfizer Inc. $60,456.81 Merck & Co., Inc. $59,669.30 Daimler AG $59,376.56 Coca-Cola Company $58,504.71 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. $57,921.92 United Parcel Service, Inc. Class B $57,674.42 salesforce.com, inc. -

List of Realdania's Commercial Investments in Listed Equites

List of Realdania's commercial investments in listed equites 31st December 2018 ISIN or Sedol Security name FR0000120644 Danone US3703341046 General Mills US4943681035 Kimberly-Clark NL0011794037 Ahold Delhaize US58933Y1055 Merck & Co FR0000130577 Publicis Groupe CH0038863350 Nestle CH0012032048 Roche US1890541097 Clorox FR0000120073 Air Liquide JP3422950000 Seven & I Holdings US7170811035 Pfizer JP3496400007 KDDI Corp US4404521001 Hormel Foods DK0060534915 Novo Nordisk FR0000133308 Orange SE0000163594 Securitas US2058871029 ConAgra Brands GB00B01FLG62 G4S FR0000121220 Sodexo CH0012255151 Swatch JP3862400003 Makita GB0032089863 Next JP3982100004 Lawson US5132721045 Lamb Weston US94106L1098 Waste Management IE0004906560 Kerry Group US6092071058 Mondelez International JP3116000005 Asahi Group GB0009252882 GlaxoSmithKline JP3205800000 Kao JP3421800008 Secom JP3469000008 Mitsubishi Tanabe DE000A1EWWW0 Adidas IT0005252207 Campari JP3258000003 Kirin GB00B03MLX29 Royal Dutch Shell Plc-A shs (GB) US8923561067 Tractor Supply Co CH0012005267 Novartis AG US92939U1060 WEC Energy Group Inc US91324P1021 United Health Group Inc. NL0011540547 ABN AMRO Group NV GB00B0744B38 Bunzl PLC US2333311072 DTE Energy Co US58933Y1055 Merck & Co Inc US0367521038 Anthem Inc US0028241000 Abbott Laboratories US7185461040 Phillips 66 US30231G1022 Exxon Mobil Corporation CH0012032048 Roche Holdings CA7751092007 Rogers Communications Inc CA7800871021 Royal Bank of Canada US4824801009 KLA-Tencor Corp US92343V1044 Verizon Communications Inc US89417E1091 Travelers Cos Inc/The