Joaquin Costa and Miguel De Unamuno's Searches for National Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish Nationalism Diego Muro, Alejandro Quiroga

Spanish nationalism Diego Muro, Alejandro Quiroga To cite this version: Diego Muro, Alejandro Quiroga. Spanish nationalism. Ethnicities, SAGE Publications, 2005, 5 (1), pp.9-29. 10.1177/1468796805049922. hal-00571834 HAL Id: hal-00571834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00571834 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARTICLE Copyright © 2005 SAGE Publications (London,Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) 1468-7968 Vol 5(1): 9–29;049922 DOI:10.1177/1468796805049922 www.sagepublications.com Spanish nationalism Ethnic or civic? DIEGO MURO King’s College London ALEJANDRO QUIROGA London School of Economics ABSTRACT In recent years, it has been a common complaint among scholars to acknowledge the lack of research on Spanish nationalism. This article addresses the gap by giving an historical overview of ‘ethnic’ and ‘civic’ Spanish nationalist discourses during the last two centuries. It is argued here that Spanish nationalism is not a unified ideology but it has, at least, two varieties. During the 19th-century, both a ‘liberal’ and a ‘conservative-traditionalist’ nationalist discourse were formu- lated and these competed against each other for hegemony within the Spanish market of ideas. -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Existentialism

03/05/2017 Existentialism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Existentialism First published Mon Aug 23, 2004; substantive revision Mon Mar 9, 2015 Like “rationalism” and “empiricism,” “existentialism” is a term that belongs to intellectual history. Its definition is thus to some extent one of historical convenience. The term was explicitly adopted as a self description by JeanPaul Sartre, and through the wide dissemination of the postwar literary and philosophical output of Sartre and his associates—notably Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice MerleauPonty, and Albert Camus —existentialism became identified with a cultural movement that flourished in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s. Among the major philosophers identified as existentialists (many of whom—for instance Camus and Heidegger—repudiated the label) were Karl Jaspers, Martin Heidegger, and Martin Buber in Germany, Jean Wahl and Gabriel Marcel in France, the Spaniards José Ortega y Gasset and Miguel de Unamuno, and the Russians Nikolai Berdyaev and Lev Shestov. The nineteenth century philosophers, Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, came to be seen as precursors of the movement. Existentialism was as much a literary phenomenon as a philosophical one. Sartre's own ideas were and are better known through his fictional works (such as Nausea and No Exit) than through his more purely philosophical ones (such as Being and Nothingness and Critique of Dialectical Reason), and the postwar years found a very diverse coterie of writers and artists linked under the term: retrospectively, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, and Kafka were conscripted; in Paris there were Jean Genet, André Gide, André Malraux, and the expatriate Samuel Beckett; the Norwegian Knut Hamsun and the Romanian Eugene Ionesco belong to the club; artists such as Alberto Giacometti and even Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning, and filmmakers such as JeanLuc Godard and Ingmar Bergman were understood in existential terms. -

Nietzsche and Unamuno: Connections and Differences

ISSN: 2347-7474 International Journal Advances in Social Science and Humanities Available online at: www.ijassh.com RESEARCH ARTICLE Nietzsche and Unamuno: Connections and Differences Maria Rodriguez Garcia University Pablo Olavide, Seville, Spain. Abstract This article tries to show the similarities and differences between the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche and Miguel de Unanmuno. For this we refer mainly to the role of Nietzsche's superman and how it is present in the Spanish thinking of the early twentieth century through the work of Miguel de Unamuno. Keywords: Philosophy, Friedrich Nietzsche, Miguel de Unamuno, Metaphysic, Literature. Introduction The last puffs of the 19th century were the negative and the contrast with his writings germ of the approach of the work of situate us in a problematic position, as they Nietzsche to our country, which remained are not few the references found by the sad by the traces of the at present known studious of an influence (more or less like Crisis of the 98 [1] like historical event imperfect) of the thought nietzschean in the that would seat the bases of what would be works of the Spanish thinker. Special the imminent 20th century. According to attention deserves in this point Así hablaba Gonzalo Sobejano in his work Nietzsche in Zaratustra, whose exaltation of the Spain [2], the approach of the authors of the superman and of the eternal return was 98 to the work of Nietzsche was mediated by fundamental in the primes of the Spanish Paul Schmitz, writer and Swiss his pianist 20th century and, specifically, in the that came to Spain in 1899 to remedy an writings unamunianos of these years. -

Authority with Ambiguity in Kierkegaard and Unamuno's Authorship

JACOBO ZABALO ARS BREVIS 2007 AUTHORITY WITH AMBIGUITY IN KIERKEGAARD AND UNAMUNO'S AUTHORSHIP Jacobo Zabalo Kierkegaard presentó el concepto de autoridad en los escritos que datan del final de su vida como contrapun- to a la estrategia literaria desarrollada por medio de pseudónimos varios para la promoción de un idea parti- cular y espiritual de sujeto. Con el fin de comunicar coherentemente esta noción (esto es, sin imponer un sen- tido universal) hubo de reconocerse como autor “sin autoridad” [uden Myndighed]. La apasionada ambigüe- 176 dad de este movimiento sería asumida décadas después por Miguel de Unamuno, en quien halló póstumamente uno de sus más fieles seguidores. Sintomáticamente, el español solía referírsele como al “hermano Kierkega- ard”; pues como él creó un peculiar corpus literario: com- binando ficción y no ficción, concibió autores imagina- rios, escribió novelas acerca de cómo escribir una novela y plasmó pensamientos filosóficos a partir de la explo- tación de sus recursos poéticos, completamente afectado por una profunda inquietud religiosa. 1. About the Christian Paradigm Miguel de Unamuno openly refused to conceive faith as a pre- established belief in the unseen, a belief in that which could not be seen. He rather comprehended it as a creation of what actually (as a matter of fact and in actu) is being-unseen: “¿Creer lo que no vimos? -asks himself rhetorically- ¡Creer lo que no vimos, no!, sino crear lo que no vemos. Crear lo que no vemos, sí, crearlo, y vivir- lo, y consumirlo, y volverlo a crear y consumirlo de nuevo vivién- ARS BREVIS 2007 AUTHORITYWITH AMBIGUITY IN KIERKEGAARD AND UNAMUNO’S AUTHORSHIP dolo otra vez, para otra vez crearlo… y así; en incesante tormento vital”.1 It is by seizing the similarities of the Spanish terms creer (to believe) and crear (to create), that Unamuno postulates the active, passionate behaviour that shall be maintained for a spiritual com- prehension. -

The Tragic Sense of Life by Miguel De Unamuno

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Tragic Sense Of Life, by Miguel de Unamuno This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Tragic Sense Of Life Author: Miguel de Unamuno Release Date: January 8, 2005 [EBook #14636] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE *** Produced by David Starner, Martin Pettit and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO translator, J.E. CRAWFORD FLITCH DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC New York This Dover edition, first published in 1954, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the English translation originally published by Macmillan and Company, Ltd., in 1921. This edition is published by special arrangement with Macmillan and Company, Ltd. The publisher is grateful to the Library of the University of Pennsylvania for supplying a copy of this work for the purpose of reproduction. Standard Book Number: 486-20257-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 54-4730 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc. 180 Varick Street New York, N.Y. 10014 CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY ESSAY AUTHOR'S PREFACE I THE MAN OF FLESH AND BONE Philosophy and the concrete man—The man Kant, the man Butler, and the man Spinoza—Unity and continuity of the person—Man an end not a means—Intellectual necessities -

Religious Nonconformism: Methodism As Quixotism in His 1905 Talk

CHAPTER 7 A TALE OF FAITH AND LOVE: RELIGIOUS ENTHUSIASM AND NATURAL AFFECTION IN RICHARD GRAVES’ THE SPIRITUAL QUIXOTE Religious Nonconformism: Methodism as Quixotism In his 1905 talk, “Tercentenary of Don Quixote: Cervantes in England”, delivered at the British Academy, Fitzmaurice-Kelly affirms that “The Spiritual Quixote of Graves, published in 1773, and similar productions of this period have lost whatever interest that they may once have had”.1 Labelled by the literature as an anti-Methodist satire, a minor novel like The Spiritual Quixote is of interest, I argue, because, like other previous canonical eighteenth-century texts, it takes Quixotism as a critique of Methodism. A Nonconformist Christian confession born within the Church of England, Methodism was, spiritually and politically, a cultural institution “with the sovereign at its head”.2 Graves’ novel fills yet another gap in the Enlightenment cultural critique filtered through the lens of Quixotism, in that it draws attention to the hazardous practice encouraged by a sectarian movement driven by religious enthusiasm as true faith in God. My intention is not to probe the historical and political factors underlying this issue, but to look at Graves’ not wholly satirical treatment of Methodism as religious practice and spiritual reform in an “orthodox Quixotic narrative”,3 as Scott Paul Gordon points out. The Spiritual Quixote is a comic romp born of an incident that took place when Graves was a rector at Claverton. An itinerant preacher, who was a shoemaker by trade, settled in his parish for a while and 1 Fitzmaurice-Kelly, “Tercentenary of Don Quixote: Cervantes in England”, 16-17 (emphasis added). -

Unamuno's “Quixotism”

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts FLESH AND BONE: UNAMUNO’S “QUIXOTISM” AS AN INCARNATION OF KIERKEGAARD’S “RELIGIOUSNESS A” A Dissertation in Philosophy By Mary Ann Alessandri © 2010 Mary Ann Alessandri Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 ii The dissertation of Mary Ann Alessandri was reviewed and approved* by the following: Shannon Sullivan Professor of Philosophy, Women’s Studies and African and African American Studies Head of the Department of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser Co-Chair of Committee Daniel Conway, Professor and Department Head Philosophy Department, Texas A&M University Co-Chair of Committee Special Member Brady Bowman Assistant Professor of Philosophy John P. Christman Associate Professor of Philosophy and Political Science Nicolás Fernández-Medina Assistant Professor of Spanish Literature, Department of Spanish, Italian and Portuguese *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT My dissertation explores the philosophical kinship between the existentialist thinkers Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) and Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) in an attempt to resurrect an ethically religious way of life. In Kierkegaard’s writings one can find a description of a passionately committed way of life that is distinguishable from both his conception of ethics and his version of Christianity. He calls this form of ethical religion or religious ethics “Religiousness A,” but he fails to give a vivid illustration of it that definitively distinguishes it from ethics and Christianity. As a result, the scholarship on Religiousness A is impoverished, and what would otherwise amount to a promising new way of being religious in a secular world has been largely regarded as unimportant or simply a watered-down version of Christianity. -

NYU Madrid ARTH-UA.9417 Art and Social Movements in Spain 1888- 1939

NYU Madrid ARTH-UA.9417 Art and Social Movements in Spain 1888- 1939 Instructor Information ● Name: Julia Doménech ● Office hours: Tuesdays: 7.30-8.30pm ● Email address: [email protected] Course Description This survey examines the major artists and institutions that shaped the development of modern art in Spain from 1888, the date of Barcelona's Universal Exposition, to the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939. The course takes as its working model the complex question of art's relation to social movements, including: the rising tides of cultural and political nationalism in the Basque and Catalan regions; the Colonial Disaster of 1898 and the question of national regeneration; the impact of fin-del-siglo anarchist and workers’ movements; the rise of authoritarian politics with the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera; and the ideological struggles and social violence unleashed during the Spanish Civil War. Class sessions examine the complex roles played by some of Spain's most prominent artists and architects -- Antoni Gaudí, Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Luis Buñuel, Josep Lluís Sert, and Salvador Dalí -- and their multivalent responses to modernization, political instability, and social praxis. ● Co-requisite or prerequisite: N/A ● Class meeting days and times: Tuesdays 4.30-7.20 pm Desired Outcomes Upon Completion of this Course, students will be able to: ● Providing students with a working knowledge of the development of modern art in Spain. Page 1 ● Exploring the complex and highly mediated relations that obtain between art and politics in relation to both progressive and conservative/reactionary social movements. Assessment Components Assignment 1: Group Presentations on a temporary exhibition. -

The Rhetoric of Miguel De Unamuno's Newspaper

“WITH WEAPONS OF BURNING WORDS”: THE RHETORIC OF MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO’S NEWSPAPER WRITINGS A Dissertation by ELIZABETH RAY EARLE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Nathan Crick Committee Members, Leroy Dorsey Alberto Moreiras Randall Sumpter Head of Department, Kevin Barge August 2019 Major Subject: Communication Copyright 2019 Elizabeth Ray Earle ABSTRACT Although he was most famous for his books of fiction and philosophy, 20th century Spanish public intellectual Miguel de Unamuno also wrote a large body of newspaper articles in which he critiqued politics and society during his lifetime. Unamuno lived during a polarized time in Spanish history, and he witnessed many political and social conflicts, including the Third Carlist War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, a military dictatorship, the Second Spanish Republic, Franco’s military coup, and the Spanish Civil War. In the midst of this atmosphere of conflict and polarization, Unamuno used the medium of the newspaper to diagnose Spain’s problem and to present possible solutions. This project examines the rhetorical style that Unamuno developed in response to his political context, as he examined Spanish society and the various political regimes in Spain. As he defined the problem, Unamuno characterized it as one of ideology, excess rationalism, and inauthenticity. To solve this problem, Unamuno approached it in two ways. First, he acted as what he called an “idea-breaker,” or as one who assumes an attitude of skepticism and uses individual thought to break down ideas and dogma. -

Imperial Emotions

Imperial Emotions LUP, Krauel, Imperial Emotions.indd 1 21/10/2013 12:57:14 Contemporary Hispanic and Lusophone Cultures Series Editor L. Elena Delgado, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Richard Rosa, Duke University Series Editorial Board Jo Labanyi, New York University Chris Perriam, University of Manchester Lisa Shaw, University of Liverpool Paul Julian Smith, CUNY Graduate Center This series aims to provide a forum for new research on modern and contemporary hispanic and lusophone cultures and writing. The volumes published in Contemporary Hispanic and Lusophone Cultures reflect a wide variety of critical practices and theoretical approaches, in harmony with the intellectual, cultural and social developments that have taken place over the past few decades. All manifestations of contemporary hispanic and lusophone culture and expression are considered, including literature, cinema, popular culture, theory. The volumes in the series will participate in the wider debate on key aspects of contemporary culture. 1 Jonathan Mayhew, The Twilight of the Avant-Garde: Contemporary Spanish Poetry 1980–2000 2 Mary S. Gossy, Empire on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown 3 Paul Julian Smith, Spanish Screen Fiction: Between Cinema and Television 4 David Vilaseca, Queer Events: Post-Deconstructive Subjectivities in Spanish Writing and Film, 1960s to 1990s 5 Kirsty Hooper, Writing Galicia into the World: New Cartographies, New Poetics 6 Ann Davies, Spanish Spaces: Landscape, Space and Place in Contemporary Spanish Culture 7 Edgar Illas, Thinking -

The Educational Regenerationism in Spain

Universal Journal of Educational Research 9(3): 540-548, 2021 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2021.090313 The Educational Regenerationism in Spain Rafael Salinas, Isabel Alvarez* Department of Systematic and Social Pedagogy, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain Received January 5, 2021; Revised February 7, 2021; Accepted March 6, 2021 Cite This Paper in the following Citation Styles (a): [1] Rafael Salinas, Isabel Alvarez, "The Educational Regenerationism in Spain," Universal Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 540-548, 2021. DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2021.090313. (b): Rafael Salinas, Isabel Alvarez (2021). The Educational Regenerationism in Spain. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 9(3), 540-548. DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2021.090313. Copyright©2021 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The aim of this paper is to show how the Institution of Education (FIE), 1876, and The National Spanish Pedagogical Conferences between 1882 and 1908 Pedagogical Museum, 1882. While the FIE is constituted influenced the promotion of innovative teaching at that as a response to the coercion of academic freedom time. Pedagogical Conferences were the only forum represented by the Orovio sentence, the Museum is the through which both rural and urban schoolteachers were organ whereby all the advances in primary education have able to implement new educational ideas. Books were not been already verified in other countries and introduced in available, so at that time schoolteachers would write their Spain, in collaboration with the mission of the Normal own textbooks to use in their schools. -

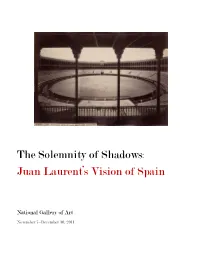

The Solemnity of Shadows: Juan Laurent's Vision of Spain

The Solemnity of Shadows: Juan Laurent’s Vision of Spain National Gallery of Art November 7–December 30, 2011 Checklist of the exhibition Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are by Juan Laurent and are albumen silver prints made from wet collodion negatives; dates are those of the collodion negatives. 1 Entrance to Toledo by way of the Alcántara 3 Plaza de la Constitución, Valencia, 1870 Bridge, c. 1864–1870 Recent research suggests that this photograph, previously Toledo is the ancient capital of Castile. Dominating the attributed to Juan Laurent, was actually taken by Julio skyline in this photograph is the sixteenth-century Alcázar Ainaud (1837–1900), a French-born photographer working on the site of old Roman, Visigoth, and Moorish citadels. for the Laurent Company in the eastern Spanish provinces The Puente de Alcántara, the most famous of the city’s in 1870–1872. The two churches in the background are the bridges, was begun in 1259 and rebuilt several times. In Basílica de la Virgen de los Desamapardos (begun in 1652) 1870, Laurent began printing a catalogue number at the and the Seu, or Cathedral of Valencia (consecrated 1238). bottom of each photograph in a distinctive label that Between them is a 1566 addition to the cathedral known as included the name of the city or art collection, the title of the Obra Nueva, a tribunal gallery for viewing ecclesiastic the subject, and his trade name. At first, the trade name on spectacles. José Martínez Sánchez, with whom Laurent the labels was simply J. Laurent, but in 1875 it became J.