CARTELS Beverley Moore a Thesis Submitted in Conformity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact Book 2004 Fact Book 2004

Fact Book 2004 Fact Book 2004 Table of Contents Welcome Letter 2 Management Executive Team 4 Board of Directors 4 Operations Media Networks Profile 6 Business 7 Key Dates 8 Fast Facts 10 Data 13 Studio Entertainment Profile 22 Business 22 Key Dates 23 Fast Facts 25 Data 27 Parks and Resorts Profile 34 Business 34 Key Dates 35 Fast Facts 40 Data 42 Consumer Products Profile 48 Business 48 Key Dates 49 Fast Facts 51 History 55 Financials Income Statements 73 Balance Sheets 76 Cash Flows 78 Quarterly Statements 2004 80 Quarterly Statements 2003 82 Financial Ratios 85 Stock Statistics 86 Reconciliations 87 1 Fact Book 2004 Welcome to The Walt Disney Company Fact Book 2004 The Walt Disney Company’s Fact Book 2004 profiles the company’s key business segments and performance, and highlights key events from throughout the company’s 81 year history. The Walt Disney Company strives to be one of the world’s leading producers and providers of quality entertainment and information. Our investment in new content and characters as well as building, nurturing and expanding our existing franchises, gives us an advantage to strengthen and reinforce the affinity that consumers have with our brands and characters across all of our business segments. By growing operating income, improving returns on capital and delivering strong cash flow, the company strives to provide long-term value to Disney’s shareholders. Disney enjoys competitive advantages that underpin all of our successes, both financial and creative. In the long run, we prosper from the inventiveness of our film, television, and other programming; our ability to connect with our audiences; the use of technological advances to enhance our products; the opportunity to delight people around the world with our toys, clothing and other consumer products; and the ability to surprise our Guests with magical experiences at the parks, cruise lines and resorts. -

Print Journalism: a Critical Introduction

Print Journalism A critical introduction Print Journalism: A critical introduction provides a unique and thorough insight into the skills required to work within the newspaper, magazine and online journalism industries. Among the many highlighted are: sourcing the news interviewing sub-editing feature writing and editing reviewing designing pages pitching features In addition, separate chapters focus on ethics, reporting courts, covering politics and copyright whilst others look at the history of newspapers and magazines, the structure of the UK print industry (including its financial organisation) and the development of journalism education in the UK, helping to place the coverage of skills within a broader, critical context. All contributors are experienced practising journalists as well as journalism educators from a broad range of UK universities. Contributors: Rod Allen, Peter Cole, Martin Conboy, Chris Frost, Tony Harcup, Tim Holmes, Susan Jones, Richard Keeble, Sarah Niblock, Richard Orange, Iain Stevenson, Neil Thurman, Jane Taylor and Sharon Wheeler. Richard Keeble is Professor of Journalism at Lincoln University and former director of undergraduate studies in the Journalism Department at City University, London. He is the author of Ethics for Journalists (2001) and The Newspapers Handbook, now in its fourth edition (2005). Print Journalism A critical introduction Edited by Richard Keeble First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX9 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Selection and editorial matter © 2005 Richard Keeble; individual chapters © 2005 the contributors All rights reserved. -

MB-01 COVER.Indd

SHANAH TOVAH uc,f, vcuy vbak INFLUENCERS Plus: Fiction by Ella Burakowski M THE CANADIAN JEWISH NEWS B2 [ RH 5776 ] SEPTEMBER 10, 2015 Supreme Court judge broke new ground A colourful life Employment, she coined the term and in the spotlight the concept of “employment equity,” as a strategy to remedy workplace dis- arbara Amiel has been called a lot of crimination faced by women, Aborigin- B things, but boring shouldn’t be one of al Peoples, people with disabilities and them. visible minorities. Known for her outspoken, politically That same year she was the first conservative column in Maclean’s maga- woman chair of the Ontario Labour Re- zine as much as for her marriage to for- lations Board and later became the first mer media baron Conrad Black, Amiel is Barbara Amiel Rosalie Silberman Abella woman in the British Commonwealth to a British Canadian journalist, writer and head a law reform commission. socialite. In 2001, Amiel made a splash when she osalie Silberman Abella, the first In 2004, she was appointed to the Su- Born in England, Amiel moved with her reported in the British weekly magazine, R Jewish woman appointed to the Su- preme Court, where she has written de- family to Hamilton, Ont., as an adolescent, The Spectator, that the then-French am- preme Court of Canada has been shat- cisions on family law, employment law, but spent years living on her own and bassador to Britain had called Israel “that tering the glass ceiling her entire life. youth criminal justice and human rights. holding various jobs to support herself af- shitty little country” to Black at a private Born to Holocaust survivor parents in She continues to be involved in issues ter her mother and stepfather pushed her dinner party he was hosting. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2019 FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum Alan Bowers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons Recommended Citation Bowers, Alan, "FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1921. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1921 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUTURE WORLD(S): A Critique of Disney's EPCOT and Creating a Futuristic Curriculum by ALAN BOWERS (Under the Direction of Daniel Chapman) ABSTRACT In my dissertation inquiry, I explore the need for utopian based curriculum which was inspired by Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center. Theoretically building upon such works regarding utopian visons (Bregman, 2017, e.g., Claeys 2011;) and Disney studies (Garlen and Sandlin, 2016; Fjellman, 1992), this work combines historiography and speculative essays as its methodologies. In addition, this project explores how schools must do the hard work of working toward building a better future (Chomsky and Foucault, 1971). Through tracing the evolution of EPCOT as an idea for a community that would “always be in the state of becoming” to EPCOT Center as an inspirational theme park, this work contends that those ideas contain possibilities for how to interject utopian thought in schooling. -

Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 52 | Issue 3 Article 3 5-2000 Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc. and Mel Karmazin President and Chief Executive Officer of CBS Corp. Summer M. Redstone Viacom Mel Karmazin CBS Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation Redstone, Summer M. and Karmazin, Mel (2000) "Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc. and Mel Karmazin President and Chief Executive Officer of CBS Corp.," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 52: Iss. 3, Article 3. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol52/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc. and Mel Karmazin President and Chief Executive Officer of CBS Corp.* Viacom CBS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 499 II. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE REVIEW .............................................. 503 III. FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION REVIEW ................... 507 I. INTRODUCTION On September 6, 1999, Viacom Inc. and CBS Corporation agreed to combine the two companies in a merger of equals. Sumner Redstone will lead the new company, to be called Viacom, in his continued role as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, as well as majority shareholder. -

Culpable Neutrality Ronald Channing P 13 Hat Is the Moral Worth of a Neutrality out Its Entire Being Like a Stick of Seaside Rock

Volume LII No. 8 August 1997 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss... Dr Wiener's monument /s /t possible to be equidistant from good and evil? Anthony Grenville p.4 New Holocaust Research Project Culpable neutrality Ronald Channing p 13 hat is the moral worth of a neutrality out its entire being like a stick of seaside rock. Be based on equidistance from the combat sides, it requires less effort of the imagination to W ants in a struggle of good versus evil? envisage the Mosleys making Britain judenrein than (Para)normal For an answer to this question one need look no to see Jessica Mitford as a Madame Ceausescu clone. life further than Switzerland which, thanks to the In Nazi-occupied Britain deportations would have pressure of world opinion, is daily made more aware been the task of the SS, dubbed the 'black corps' on aranormal - of how reprehensible its wartime conduct had been. account of their fear-inspiring uniforms. Das dictionary But for all the tumbling of skeletons out of the Schtvarze Korps was the organ of the SS and like definition P cupboards of the wartime neutrals - the Swiss, the Der Stiirmer, reached millions of readers via display 'beyond normal Swedes, the Spaniards, the Portuguese, the Vatican cases up and down the country. explanation' - is - indifference to moral issues has by no means van the appropriate term Unlike Der Stiirmer's Julius Streicher, who was ished from the contemporary world. for describing hanged at Nuremberg, Schivarze Korps editor A case in point is the high esteem in which Ernst the fact (see p. -

Stations Monitored

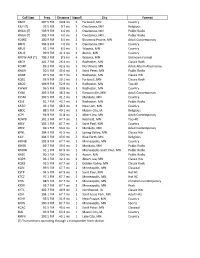

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Broadcast Radio

Call Sign Freq. Distance Signal City Format KBGY 107.5 FM 10.8 mi. 5 Faribault, MN Country KJLY (T) 93.5 FM 0.7 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Religious KNGA (T) 103.9 FM 4.0 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Public Radio KNGA (T) 105.7 FM 4.0 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Public Radio KOWZ 100.9 FM 8.5 mi. 5 Blooming Prairie, MN Adult Contemporary KRFO 104.9 FM 2.0 mi. 5 Owatonna, MN Country KRUE 92.1 FM 8.5 mi. 5 Waseca, MN Country KAUS 99.9 FM 31.4 mi. 4 Austin, MN Country KFOW-AM (T) 106.3 FM 8.5 mi. 4 Waseca, MN Unknown Format KRCH 101.7 FM 26.4 mi. 4 Rochester, MN Classic Rock KCMP 89.3 FM 42.6 mi. 3 Northfield, MN Adult Album Alternative KNGA 90.5 FM 45.6 mi. 3 Saint Peter, MN Public Radio KNXR 97.5 FM 43.7 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Classic Hits KQCL 95.9 FM 19.1 mi. 3 Faribault, MN Classic Rock KROC 106.9 FM 52.9 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Top-40 KWWK 96.5 FM 30.8 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Country KYBA 105.3 FM 38.3 mi. 3 Stewartville, MN Adult Contemporary KYSM 103.5 FM 41.2 mi. 3 Mankato, MN Country KZSE 91.7 FM 43.7 mi. 3 Rochester, MN Public Radio KATO 93.1 FM 48.2 mi. 2 New Ulm, MN Country KBDC 88.5 FM 49.1 mi. 2 Mason City, IA Religious KCPI 94.9 FM 31.8 mi. -

Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 3 Article 3 5-2000 Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc. and Mel Karmazin esidentPr and Chief Executive Officer of CBS Corp. Summer M. Redstone Viacom Mel Karmazin CBS Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation Redstone, Summer M. and Karmazin, Mel (2000) "Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc. and Mel Karmazin esidentPr and Chief Executive Officer of CBS Corp.," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 52 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol52/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Joint Statement of Sumner M. Redstone Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Viacom Inc. and Mel Karmazin President and Chief Executive Officer of CBS Corp.* Viacom CBS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 499 II. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE REVIEW .............................................. 503 III. FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION REVIEW ................... 507 I. INTRODUCTION On September 6, 1999, Viacom Inc. and CBS Corporation agreed to combine the two companies in a merger of equals. Sumner Redstone will lead the new company, to be called Viacom, in his continued role as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, as well as majority shareholder. -

Asper Nation Other Books by Marc Edge

Asper Nation other books by marc edge Pacific Press: The Unauthorized Story of Vancouver’s Newspaper Monopoly Red Line, Blue Line, Bottom Line: How Push Came to Shove Between the National Hockey League and Its Players ASPER NATION Canada’s Most Dangerous Media Company Marc Edge NEW STAR BOOKS VANCOUVER 2007 new star books ltd. 107 — 3477 Commercial Street | Vancouver, bc v5n 4e8 | canada 1574 Gulf Rd., #1517 | Point Roberts, wa 98281 | usa www.NewStarBooks.com | [email protected] Copyright Marc Edge 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (access Copyright). Publication of this work is made possible by the support of the Canada Council, the Government of Canada through the Department of Cana- dian Heritage Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Printing, Cap-St-Ignace, QC First printing, October 2007 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Edge, Marc, 1954– Asper nation : Canada’s most dangerous media company / Marc Edge. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55420-032-0 1. CanWest Global Communications Corp. — History. 2. Asper, I.H., 1932–2003. I. Title. hd2810.12.c378d34 2007 384.5506'571 c2007–903983–9 For the Clarks – Lynda, Al, Laura, Spencer, and Chloe – and especially their hot tub, without which this book could never have been written. -

$62,810,000 Anaheim Public Financing Authority Revenue

NEW ISSUE - BOOK-ENTRY ONLY In the opinion of Co-Bond Counsel, under existing law and assumingcompliance with the tax covenant describedherein, the interest receivedby the owners of the 1993Bonds is excluded from gross income for Federal income tax purposesand is not a specific preferenceitem for purposesof the Federal alternative minimum tax. In the further opinion of Co-Bond Counsel, the interest received by the owners of the 1993 Bonds is exempt from personal income taxes of the State of California. See, however, "TAX EXEMPTION" herein for a descnption of other taxes on corporations. Credit Ratings: Moody's: Aaa Duff & Phelps: AAA Standard & Poor's: AAA (see "Credit Ratings" herein) $62,810,000 Anaheim Public Financing Authority Revenue Bonds, Second Series 1993 (City of Anaheim Electric Utility San Juan Unit 4 Project) Dated: July 1, 1993 Due: October 1, as shown herein The 1993 Bonds arebeing executed and delivered as fullyregistered bonds. The 1993 Bonds when initially executed and delivered will be registered in the name of Cede & Co., as registered owner and nominee for the Depository Trust Company, New York, New York ("OTC"), and will be available to ultimate purchasers in book-entry form only in denominations of $5,000 or any integral multiple thereof. Interest on the 1993 Bonds is payable semi-annually on April l and October l of each year, commencing October l, 1993. Payments of principal of and interest on the 1993 Bonds are to be made to purchasers by OTC through OTC Participants. Purchasers will not receive physical delivery of the 1993 Bonds purchased by them.