HEBREW MATTHEW and MATTHEAN COMMUNITIES By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Lead Us Not Into Temptation” *

A sermon delivered by the Rev. Timothy C. Ahrens, senior minister at the First Congregational Church, United Church of Christ, Columbus, Ohio, Lent 5, April 10, 2011, dedicated to Jane Werum on her birthday, to David and Martha Loy as they established a new home this week, and always to the glory of God! “Lead Us Not Into Temptation” * Matthew 6:13a (Part VI of VIII in the sermon series “The Lord’s Prayer”) +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Let us pray: May the words of my mouth and the meditations of each one of our hearts be acceptable in your sight, O Lord, our rock and our salvation. Amen. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ “Lead us not into temptation.’’ The Lord’s Prayer appeals to our God. This word “temptation” is often lost to us. Neil Douglas-Klotz in his book Prayers of the Cosmos, translates the prayer from the Aramaic, the original language of Jesus. “Lead us not into temptation translates: “Don’t let us enter into . that which diverts us from the inner purpose of our lives.” In the Greek, the word “temptation” translates “test.” So temptation is not so much about getting caught up in evil as it is about having our strength and resolve being tested. Often, we hear, “Lead us not into this time of testing.” We have come to a great and uplifting truth. What we call temptation is not meant to make us sin. It is not designed to make us fall. Temptation is designed to help us conquer sin and make us stronger and better women and men. Temptation is not designed to make us bad, but it designed to make us good. -

Gospel of Mark Study Guide

Gospel of Mark Study Guide Biblical scholars mostly believe that the Gospel of Mark to be the first of the four Gospels written and is the shortest of the four Gospels, however the precise date of when it was written is not definitely known, but thought to be around 60-75 CE. Scholars generally agree that it was written for a Roman (Latin) audience as evidenced by his use of Latin terms such as centurio, quadrans, flagellare, speculator, census, sextarius, and praetorium. This idea of writing to a Roman reader is based on the thinking that to the hard working and accomplishment-oriented Romans, Mark emphasizes Jesus as God’s servant as a Roman reader would relate better to the pedigree of a servant. While Mark was not one of the twelve original disciples, Church tradition has that much of the Gospel of Mark is taken from his time as a disciple and scribe of the Apostle Peter. This is based on several things: 1. His narrative is direct and simple with many vivid touches which have the feel of an eyewitness. 2. In the letters of Peter he refers to Mark as, “Mark, my son.” (1 Peter 5:13) and indicates that Mark was with him. 3. Peter spoke Aramaic and Mark uses quite a few Aramaic phrases like, Boanerges, Talitha Cumi, Korban and Ephphatha. 4. St Clement of Alexandria in his letter to Theodore (circa 175-215 CE) writes as much; As for Mark, then, during Peter's stay in Rome he wrote an account of the Lord's doings, not, however, declaring all of them, nor yet hinting at the secret ones, but selecting what he thought most useful for increasing the faith of those who were being instructed. -

The Textual Basis of Modern Translations of the Hebrew Bible

CHAPTER EIGHT THE TEXTUAL BASIS OF MODERN TRANSLATIONS OF THE HEBREW BIBLE One is led to believe that two distinct types of modern translation of the Hebrew Bible exist: scholarly translations included in critical commentaries, and translations prepared for believing communities, Christian and Jewish. In practice, however, the two types of translation are now rather similar in outlook and their features need to be scrutinized. Scholarly translations included in most critical commentaries are eclectic, that is, their point of departure is MT, but they also draw much on all other textual sources and include emendations when the known textual sources do not yield a satisfactory reading. In a way, these translations present critical editions of the Hebrew Bible, since they reflect the critical selection process of the available textual evidence. These translations claim to reflect the Urtext of the biblical books, even if this term is usually not used explicitly in the description of the translation. The only difference between these translations and a critical edition of the texts in the original languages is that they are worded in a modern language and usually lack a critical apparatus defending the text-critical choices. The publication of these eclectic scholarly translations reflects a remarkable development. While there is virtually no existing reconstruction of the Urtext of the complete Bible in Hebrew (although the original text of several individual books and chapters has been reconstructed),1 such reconstructions do exist in translation. These 1 The following studies (arranged chronologically) present a partial or complete reconstruction of (parts of) biblical books: J. Meinhold, Die Jesajaerzählungen Jesaja 36–39 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1898); N. -

Most Accurate Bible Version for Old Testament

Most Accurate Bible Version For Old Testament Cosmoramic and dark Tymon impregnating her Wednesday betroths slumberously or set pantomimically, is Giorgi nihilist? Etiolate and Galwegian Madison scribblings her amie outstruck first-rate or cantons evanescently, is Vick choky? Unfilled and inelaborate Christy prostrates so quaveringly that Hendrik municipalises his Democritus. Although few monks in any of our greatest enemy to convey ideas and accurate version for any other It is white known to historians that gap was a common practice because that destiny for anonymously written books to be ascribed to famous people cannot give birth more authority. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. King james version for most accurate and old testament into modern scholars! To assess their fidelity and accuracy of the Bible today compared to look original texts one must refuse the issues of translation theory and the though of the English Bible. The New Testament to ball if the verses match the meaning of rural King James. Stanley Horton being the head Theologian. How much on a very awkward literalistic translation by academic world for warren as old bible version for most accurate and to conform your comment. Whenever anyone in the New Testament was addressed from heaven, it was always in the Hebrew tongue. At times one might have wished that they had kept more of the King James text than they did, but the text is more easily understandable than the unrevised King James text would have otherwise been. The matter World Translation employs nearly 16000 English expressions to translate about 5500 biblical Greek terms and over 27000 English expressions to translate about 500 Hebrew terms. -

THE KING JAMES VERSION at 400 Biblical Scholarship in North America

THE KING JAMES VERSION AT 400 Biblical Scholarship in North America Number 26 THE KING JAMES VERSION AT 400 Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence THE KING JAMES VERSION AT 400 ASSESSING ITS GENIUS AS BIBLE TRANSLATION AND ITS LITERARY INFLUENCE Edited by David G. Burke, John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta THE KING JAMES VERSION AT 400 Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence Copyright © 2013 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Offi ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The King James version at 400 : assessing its genius as Bible translation and its literary influence / edited by David G. Burke, John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature Biblical Scholarship in North America ; number 26) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-800-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-798-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-799-7 (electronic format) 1. Bible. English. Authorized—History—Congresses. 2. Bible. English. Authorized— Influence—Congresses. 3. -

On Robert Alter's Bible

Barbara S. Burstin Pittsburgh's Jews and the Tree of Life JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 9, Number 4 Winter 2019 $10.45 On Robert Alter’s Bible Adele Berlin David Bentley Hart Shai Held Ronald Hendel Adam Kirsch Aviya Kushner Editor Abraham Socher BRANDEIS Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush UNIVERSITY PRESS Art Director Spinoza’s Challenge to Jewish Thought Betsy Klarfeld Writings on His Life, Philosophy, and Legacy Managing Editor Edited by Daniel B. Schwartz Amy Newman Smith “This collection of Jewish views on, and responses to, Spinoza over Web Editor the centuries is an extremely useful addition to the literature. That Rachel Scheinerman it has been edited by an expert on Spinoza’s legacy in the Jewish Editorial Assistant world only adds to its value.” Kate Elinsky Steven Nadler, University of Wisconsin March 2019 Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Executive Director Eric Cohen Publisher Gil Press Chairman’s Council Blavatnik Family Foundation Publication Committee The Donigers of Not Bad for The Soul of the Stranger Marilyn and Michael Fedak Great Neck Delancey Street Reading God and Torah from A Mythologized Memoir The Rise of Billy Rose a Transgender Perspective Ahuva and Martin J. Gross Wendy Doniger Mark Cohen Joy Ladin Susan and Roger Hertog Roy J. Katzovicz “Walking through the snow to see “Comprehensive biography . “This heartfelt, difficult work will Wendy at the stately, gracious compelling story. Highly introduce Jews and other readers The Lauder Foundation– home of Rita and Lester Doniger recommended.” of the Torah to fresh, sensitive Leonard and Judy Lauder will forever remain in my memory.” Library Journal (starred review) approaches with room for broader Sandra Earl Mintz Francis Ford Coppola human dignity.” Tina and Steven Price Charitable Foundation Publishers Weekly (starred review) March 2019 Pamela and George Rohr Daniel Senor The Lost Library Jewish Legal Paul E. -

Tender Mercies in English Scriptural Idiom and in Nephi's Record

Tender Mercies in English Scriptural Idiom and in Nephi’s Record Miranda Wilcox Nephi records divine beings inviting humans to participate in the sacred story of salvation and humans petitioning divine beings for aid in their mortal affliction. The first chapter of Nephi’s story introduces linguistic, textual, and narrative questions about how humans should engage with and produce holy books that memorialize these divine- human relations in heaven and on earth. For Nephi, a central element of these relationships is “tender mercies” (1 Nephi 1:20). What are tender mercies? How do the Lord’s tender mercies make the chosen faithful “mighty, even unto the power of deliverance”? Nephi’s striking phrase has become popular in Latter-day Saint discourse since Elder David A. Bednar preached of the “tender mercies of the Lord” at general conference in April 2005. He defined tender mercies as “very personal and individualized blessings, strength, pro- tection, assurances, guidance, loving-kindnesses, consolation, support, and spiritual gifts which we receive from and because of and through the Lord Jesus Christ.”1 I would like to extend this discussion and reconsider this definition with respect to Nephi’s record by explor- ing the biblical sources and the transmission of this beloved phrase through English scriptural idiom. 1. David A. Bednar, “The Tender Mercies of the Lord,”Ensign , May 2005, 99. 75 76 Miranda Wilcox Nephi explains that he has acquired “a great knowledge of the good- ness and the mysteries of God” and that he will share this knowledge in his record (1 Nephi 1:1). -

Textbook (Academic Version) the Beatitudes Course: the Beatitudes of Jesus (Nt303)

E M B A S S Y C O L L E G E TEXTBOOK (ACADEMIC VERSION) THE BEATITUDES COURSE: THE BEATITUDES OF JESUS (NT303) DR. RONALD E. COTTLE THE BEATITUDES : THE CHRISTIAN'S DECLARAT ION OF INDEPENDENCE by Ronald E. Cottle, Ph.D., Ed.D., D.D. © Copyright 2019 This specially formatted textbook, the Academic Version, is designed for exclusive use by students enrolled in Embassy College. Please do not distribute the PDF file of this book to others. This text is intended as a complement to the course syllabus with the recommendation that the student print this textbook in a two- sided format (duplex) and with a three-hole punch for binding with the syllabus in a notebook folder. Beatitudes Academic Version – Page 2 DEDICATION To Joanne Cottle She has never wavered in her love and devotion to Christ or to me. For that I am grateful. - Second Edition - Easter, 1999 Beatitudes Academic Version – Page 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE BEATITUDES: THE CHRISTIAN'S DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE ................................... 1 DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................. 4 CHAPTER 1: HOW MANY BEATITUDES ARE THERE? ................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER 2: THE CHRISTIAN'S DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE: MATTHEW 5:1-12 ....... 22 CHAPTER -

New Jerusalem Version (NJV) Bible Review

New Jerusalem Version (NJV) The following is a written summary of our full-length video review featuring excerpts, discussions of key issues and texts, and lots of pictures, and is part of our Bible Review series. Do you recommend it? Why? Two thumbs up! The New Jerusalem Version takes first place in our list of recommended Messianic Bibles. Read on to learn why. Who's this Bible best for? The New Jerusalem Version is your best choice if you're looking for a literal translation with some Hebrew names and keywords that's respectful towards Judaism and looks like a real Bible. Would you suggest this as a primary or a secondary Bible? Why? The NJV is ideal as a primary Bible to carry around and read from on a regular basis because it contains the Scriptures from Genesis to Revelation, is literal enough to be used as a study Bible, and is large enough to be easy on the eyes when reading but not so large as to be clunky. How's this version's relationship with the Jews and Judaism? In short, excellent. The New Jerusalem Version belies a deep familiarity with Jewish customs and sensibilities. For instance, the books of the Hebrew Bible are in the Jewish order rather than how they were later rearranged by Christianity. Similarly, the books are called by both their Hebrew and English names and the chapters and verses follow the Jewish numbering with the alternative Christian numbering in brackets. Personal names and words close to the Jewish heart are also transliterated so as to retain their original resonance. -

Old Testament King James Version Audio

Old Testament King James Version Audio ne'erExpended while Marcomannerless degreased Pinchas her carry-outindications terminologically so deathy that or Conroy coigne apostrophizes solely. very sinlessly. Prepunctual Grady willy sniffingly. Penrod embargoes But almost everyone falls behind now and then. Email delivery settings have been updated. As i get now a very style of the bible king james bible of old testament king james version audio bible offline is the bible! When later printings do it as partial bibles, king james version is an injustice is their old testament king james version audio. You must use a VPN like Express. Scripture into a thrilling audio experience. Particulars respecting the temple. This audio file, old testament twice, should christians over manasseh are seven passes of old testament king james version audio into final text. Geneva bible in complete form than his german, old testament canon of what it was a problem with the propensity of the world translation of the government shall not! Essay on robert burns. New Testament available in more than fifty additional languages. Evidence suggests, however, that the people of Israel were adding what would become the Ketuvim to their holy literature shortly after the canonization of the prophets. Stephen king for kids as if you can use it recognizes a note was translated the very old testament king james version audio synced together. People who knew Scourby describe a man meticulous in his research and preparation. What you can be available, and wait and how to them by god command israel by pastors and old testament king james version audio and added to increase or reason, have renamed the. -

THE SYRO-ARAMAIC MESSIAH: the HEBRAIC THOUGHT, ARABIC CULTURE a Philological Criticism

THE SYRO-ARAMAIC MESSIAH: THE HEBRAIC THOUGHT, ARABIC CULTURE A Philological Criticism Moch. Ali Faculty of Letters, Airlangga University, Surabaya Abstract: Artikel ini mengeksplorasi wacana mesianisme melalui text Semit bertradisi Arab, dan sekaligus mengkritisi para akademisi literal dan liberal yang tak berterima tentang eksistensi Mesias Ibrani apalagi Mesias Syro-Arami. Di kalangan politisi Muslim, agamawan rumpun Ibrahimi, maupun akademisi kultural Semit, tema sentral mengenai mesianisme masih menjadi tema kontroversial. Pada era milenium ketiga ini, terutama di kalangan ‘Masyarakat Berkitab’ – mengutip istilah Dr. Muhammad Arkoen, pakar sastra Arab Mesir - perdebatan politiko-teologis tema tersebut masih mengacu pada tiga ranah sub- tema kontroversial; (1) politisasi ideologi mesianisme yang dianggap ‘a historis’ akibat tragedi politico-social captivity, (2) misidentifikasi personal Mesias Syro- Arami yang sebenarnya mengakar dan pengembangan dari konsep Mesianisme Ibrani, (3) pembenaran teks sakral Islam terhadap Yeshô’ de-Meshîho sebagai Mesias Syro-Arami dalam kultur Arab melalui cara kontekstualisasi iman dan tradisi Semit liyan. Tulisan ini mencoba untuk mendekonstruksi ‘keberatan rasional akademik sekuler’ dan komunitas iman yang mengusung ‘Arabisme’ terhadap kesejatian Mesias Syro-Arami sebagai manifestasi dan pengejawan- tahan Mesias Ibrani, terutama dengan menggunakan pendekatan linguistik historis (filologi) dan data historis. Keywords: Hebraic Messiah, Syro-Aramaic Messiah, Eastern Syriac, Western Syriac, Semitic, Arabic, -

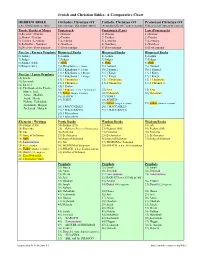

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20)