Economic History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somerset. (Kblly's

SOMERSET. (KBLLY'S - Shepton Mallet; of silk at Taunton and Shepton Mallet; 4,932; Milborne Port, 1,630; Minehead, 3,458; Fortis horsehair seating at Castle Cary, Bruton and Crewkerne; head, 3,329; Radstock, 3,690; Shepton Mallet, s,ou; bruahes at Wella; of bricks, draining pipes and the cele Street, 4,235; Wellington, 7,633; Weston-super-Mare, brated Bath brick at Bridgwater, where are also extensive 23,235; Wincanton, 1,976; Wiveliscombe, 1,316; and coach building factories ; also manufactories ef spades, Axbridge with only 1,oo8. shovels and edge tools. This county contains 487 civil parishes, and with Upon the Avon are several mills for preparing iron and the exception of the parishes of Abbot'a Leigh and copper, and other& for spinning worsted and the spinning Bedminster and parts -of Maiden Bradley and Stourton, and weaving of cotton. is ep-extensive with the diocese of Bath and Wells, There are large breweries at Shepton Mallet and is within the province of C'antt'rbury, and divided Crewkerne. into the archdeaconrjes of Bath, Taunton and Wells, The chief mineral productions are coa.{ and free the first having no/ arC'hidiaconal court, and in the stone; fullers' earth (4,920 tons in 19u). Clay, otlier two latter the bishop exercising jurisdiction concur than fuller~' earth, was raised in 19II to the extent rently with the archdeacons ; Bath archdeaconry is of 92•793 tons, value [3,865. The stone which is divided into Bath deanery, sub-divided into the dis eommonly known by the name of Bath stone is quarried trict of Bath, Chew deanery sub-divided into the in thi~t county in 'the neighbourhood of Coombe Down districts of Chew Magna, Keynsham and Portishead ; and Meneton Coombe and in the adjoining district in Thnnton arohdeac1mry is divided into Bridgwater th& county of Wilts;' Ham Hill stone is found in this deanery, .sub-divided into the districts of Bridgwater county and Doulting stone both here and in Wilts. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Thursday Volume 655 28 February 2019 No. 261 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 28 February 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 497 28 FEBRUARY 2019 498 Stephen Barclay: As the shadow spokesman, the right House of Commons hon. and learned Member for Holborn and St Pancras (Keir Starmer), said yesterday,there have been discussions between the respective Front Benches. I agree with him Thursday 28 February 2019 that it is right that we do not go into the details of those discussions on the Floor of the House, but there have The House met at half-past Nine o’clock been discussions and I think that that is welcome. Both the Chair of the Select Committee, the right hon. Member for Leeds Central (Hilary Benn) and other distinguished PRAYERS Members, such as the right hon. Member for Birkenhead (Frank Field), noted in the debate yesterday that there had been progress. It is important that we continue to [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] have those discussions, but that those of us on the Government Benches stand by our manifesto commitments in respect of not being part of a EU customs union. BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS 21. [909508] Luke Pollard (Plymouth, Sutton and NEW WRIT Devonport) (Lab/Co-op): I have heard from people Ordered, from Plymouth living in the rest of the EU who are sick I beg to move that Mr Speaker do issue his Warrant to the to the stomach with worry about what will happen to Clerk of the Crown to make out a New Writ for the electing of a them in the event of a no deal. -

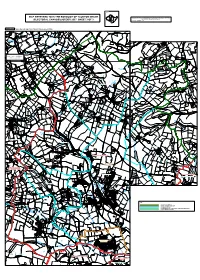

MAP REFERRED to in the BOROUGH of TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU

Sheet 3 3 MAP REFERRED TO IN THE BOROUGH OF TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU. 2 1 Tel: 023 8030 5092 Fax: 023 8079 2035 (ELECTORAL CHANGES) ORDER 2007 SHEET 3 OF 3 © Crown Copyright 2007 SHEET 3, MAP 3 Taunton Deane Borough. Parish Wards in Bishop's Lydeard Parish E N A L E AN D L L OO O P O D W UN RO Roebuck Farm Wes t So mer set Rai lway A 3 5 8 Ashfield Farm Aisholt Wood Quarry L (dis) IL H E E R T H C E E B Hawkridge Common All Saints' Church E F Aisholt AN L L A TE X Triscombe A P Triscombe Quarry Higher Aisholt G O Quarries K O Farm C (Stone) (disused) BU L OE H I R L L Quarry (dis) Flaxpool Roebuck Gate Farm Quarry (dis) Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Quarry (dis) Grid interval 1km Heathfield Farm Luxborough Farm Durborough Lower Aisholt Farm Caravan G Site O O D 'S L Triscombe A N W House Quarry E e Luxborough s t (dis) S A Farm o 3 m 5 8 e Quarry r s e (dis) t R a i l w a y B Quarry O A (dis) R P A T H L A N E G ood R E E N 'S Smokeham R H OCK LANE IL Farm L L HIL AK Lower Merridge D O OA BR Rock Farm ANE HAM L SMOKE E D N Crowcombe e A L f Heathfield K Station C O R H OL FO Bishpool RD LA Farm NE N EW Rich's Holford RO AD WEST BAGBOROUGH CP Courtway L L I H S E O H f S H e E OL S FOR D D L R AN E E O N Lambridge H A L Farm E Crowcombe Heathfield L E E R N H N T E K Quarry West Bagborough Kenley (dis) Farm Cricket Ground BIRCHES CORNER E AN Quarry 'S L RD Quarry (dis) FO BIN (dis) D Quarry e f (dis) Tilbury Park Football Pitch Coursley W e s t S Treble's Holford o m e E Quarry L -

SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS 2016 17 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER SOS GUIDE 2016 COVER Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 2

SOS_GUIDE_2016_COVER_Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 1 SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS 2016 17 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER SOS_GUIDE_2016_COVER_Half Page (Wide) Ads 11/07/2016 09:56 Page 2 Somerset Open Studios is a much-loved and thriving event and I’m proud to support it. It plays an invaluable role in identifying and celebrating a huge variety of creative activities and projects in this county, finding emerging artists and raising awareness of them. I urge you to go out and enjoy these glorious weeks of cultural exploration. Kevin McCloud Photo: Glenn Dearing “What a fantastic creative county we all live in!” Michael Eavis www.somersetartworks.org.uk SOMERSET OPEN STUDIOS #SomersetOpenStudios16 SOS_GUIDE_2016_SB[2]_saw_guide 11/07/2016 09:58 Page 1 WELCOME TO OUR FESTIVAL! About Somerset Art Works Somerset Open Studios is back again! This year we have 208 venues and nearly 300 artists participating, Placing art at the heart of Somerset, showing a huge variety of work. Artists from every investing in the arts community, enriching lives. background and discipline will open up their studios - places that are usually private working environments, SAW is an artist-led organisation and what a privilege to be allowed in! Somerset’s only countywide agency dedicated to developing visual arts, Each year, Somerset Open Studios also works with weaving together communities and individuals, organisations and schools to develop the supporting the artists who enrich our event. We are delighted to work with King’s School lives. We want Somerset to be a Bruton and Bruton School for Girls to offer new and place where people expect to exciting work from a growing generation of artistic engage with excellent visual art that talent. -

MAP REFERRED to in the BOROUGH of TAUNTONS DEANE O N a G E Portman Farm L Nurseries a N E

SHEET 1, MAP 1 Taunton Deane Borough. Ward boundaries in Taunton. Def East Lydeard Farm COTHELSTONE CP KEY Volis Farm E Kingston St Mary N A VC Primary School L Kingston St Mary N DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY Hill Farm O T G N I PARISH BOUNDARY N D e N f E F PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY Water House Farm PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY Fulford Def V O L I S H I L Nursery L P A R MAP REFERRED TO IN THE BOROUGH OF TAUNTONS DEANE O N A G E Portman Farm L Nurseries A N E (ELECTORAL CHANGES)E ORDER 2007 SHEET 1 OF 3 N A L Pickney K R A P Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU. Works Sheet 1 Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Tel: 023 8030 5092 Fax: 023 8079 2035 Hestercombe Grid interval 1km © Crown Copyright 2007 m a Hestercombe House e Hestercombe r t (Fire Brigade HQ) Farm Gotten ANE S PICKNEY L Nursery 3 n o t s Nailsbourne g in KINGSTON ST. MARY CP K 2 1 Lower Portman Farm BISHOP'S LYDEARD WARD Upper Cheddon ROAD Edgeborough OMBE TERC Farm HES BISHOP'S LYDEARD CP P I T C H E BISHOP'S LYDEARD PARISH WARD R ' S H I Deacons L STAPLEGROVE WARD L Conquest Farm Dodhill CHEDDON PARISH WARD Def A 3 B 58 ack S tream Fitzroy Cheddon Fitzpaine VC Primary School Stonehouse Farm Cheddon Fitzpaine W e s t S Higher Yarde o Rowford m Farm e rs e t R Longland's Farm a i lw a WEST MONKTON CP y King's Hall C CHEDDON FITZPAINE CP ok A Bro T s len' S Al E N L A A L N S E Y T Yarde Farm N O Vineyard M Pyrland D Hall Farm Y A e f Pyrland Farm W N E E R Sidbrook G Def E N A L D R O Ladymead F G Communtiy L -

North Down Farm Wiveliscombe, Somerset

North Down Farm Wiveliscombe, Somerset TA4 North Down Farm Wiveliscombe, Somerset TA4 A fantastic opportunity to create a large and impressive Georgian style country home set in approximately 150 acres of unspoilt countryside with rural far-reaching views. Situation & Amenities Proposed Plan & Elevations North Down Farm is situated in an elevated, unspoilt countryside setting in it’s own private valley, creating a very outline of main entrance porch secluded area. The property is located about 1.2 miles from outline of main entrance porch the small market town of Wiveliscombe, which has a variety of local shops and businesses, as well as medical, dental and veterinarian surgeries (see more at www.wiveliscombe.com). rendered elevations For wider requirements, Wellington (7.7 miles) has a more with stucco detailing WC extensive range of shops including a Waitrose supermarket and the property also sits almost midway between the large HALL BEDROOM 4 BATH 2 BEDROOM 2 centres of Taunton (11.9 miles) and Exeter (30 miles. For porch BOOT ROOM transport links, Taunton has regular rail services to Bristol 300mm plinth BATH 4 S U Temple Meads in 52 minutes, as well as Paddington in as little PE R KI N G 1 fireplace 8 as 1 hour 41 minutes. Exeter (28.8 miles) and Bristol Airports 0 0 x20 chimney flue MAIN ENTRANCE 0 (flue in wall) 0 (45.1 miles) are both easily accessible, offering connections DRAWING ROOM 183m LANDING within both the UK and to many international destinations. PROPOSED NORTH ELEVATION: STORE STUDY BEDROOM 5 2 There is also an excellent range of schooling nearby, both BATH 5 from the State and independent sectors. -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

SOMERTON RUGBY CLUB Historical News Articles 2013 - 2018

SOMERTON RUGBY CLUB Historical News Articles 2013 - 2018 Contents Emily is selected for England Rugby Centre of Excellence Program .................................. 3 Somerton RFC v Winscombe II – Saturday 3 February 2018 ................................................. 4 Saturday 16 December 2017 – Wells II v Somerton RFC ......................................................... 6 Saturday 25 November 2017: Somerton RFC v Bridgwater & Albion III .............................. 7 Saturday 11 November 2017 – Yeovil II v Somerton RFC ....................................................... 9 Saturday 4 November 2017 – Somerton RFC v Minehead Barbarians II ........................... 11 Saturday 2 September 2017 – TOR II v Somerton RFC .......................................................... 13 Saturday 4 November 2017 – Somerton RFC v Minehead Barbarians II ........................... 15 Saturday 2 September 2017 – TOR II v Somerton RFC .......................................................... 17 Saturday 4 November 2017 – Somerton RFC v Minehead Barbarians II ........................... 19 Saturday 11 November 2017 – Yeovil II v Somerton RFC ..................................................... 21 Saturday 4 November 2017 – Somerton RFC v Minehead Barbarians II ........................... 23 Saturday 2 September 2017 – TOR II v Somerton RFC .......................................................... 25 Somerton RFC does: ‘Strictly Come Dancing’ – Saturday 18 March 2017 ....................... 27 Saturday 11th February 2016 – Somerton -

Somerset VCH Newsletter Winter 2020-21 (1).Pdf

Victoria County History of Somerset Newsletter Issue 16 Winter 2020 -21 Welcome to the sixteenth edition of our newsletter. risen, as has interest in the Spanish flu and the Black Death. The great We hope you enjoy it. hope for us this winter is for effective vaccination and widespread take -up - something that has concerned the health authorities for Please pass this newsletter on to others. If you are not on our mailing list and centuries, especially in the battles against such terrifying diseases as would like to receive future copies of the newsletter please let us know by contacting us at [email protected] . smallpox and diphtheria. Mental health has also been an issue with people unable to visit family and friends or get out and about as usual. A colleague has provided an insight into some of the challenges County Editor’s Report especially those faced by dementia sufferers and how the past can be used to help. Once again this newsletter was produced under plague conditions, and quite a lot of the content reflects the current pandemic. We hope you enjoy the content. Despite the fact that the strange year of 2020 drew to an end with another lockdown and rising cases of Covid -19 we hope that you are well. Some of you may have been able to hear our 2020 VCH lecture online. If you missed it we have a précis in this newsletter. We are considering having a combined live and online lecture in future years. However, we know just how important meeting up and going out into the real world is for everyone and are still making plans for some real -life activities later in 2021! The pandemic has helped us to imagine what it must have felt like to face epidemics in the past, although they had no hope of a vaccine or effective medical treatment. -

South West Heritage Trust Somerset Heritage Centre, Brunel Way

South West Heritage Trust Somerset Heritage Centre, Brunel Way Norton Fitzwarren, Taunton, Somerset TA2 6SF 01823 278805 Dear Applicant Many thanks for your interest in applying for the position of Project Assistant with the South West Heritage Trust. The South West Heritage Trust is an independent charity, which works across Somerset and Devon, providing a broad range of heritage services and experiences. Our turnover exceeds £3.5 million and we employ nearly 100 people, working across six sites. Through our Museums Service , we run the iconic Museum of Somerset in Taunton, the Somerset Rural Life Museum in Glastonbury and the Brick and Tile Museum in Bridgwater to tell the story of the South West. We care for 3 million museum objects, including a significant fine art collection, an extensive array of costumes and textiles, a nationally notable prehistoric bone and fossil collection, a large number of coin hoards, and a growing photographic record spanning the last 100 years. We care for the written evidence of Somerset and Devon history, operating the Archives and Local Studies Services for each county. At our Heritage Centres in Taunton and Exeter, you can discover millions of documents dating from the 8 th century to the present day. If you want to research the history of families, towns, villages or events, there is no better place to start. Our Historic Environment and Estates Service supports local authorities, partners and the public by offering planning-related advice on Somerset’s archaeology and built heritage. We provide the on-line Historic Environment Record where you can find information about thousands of historic sites in Somerset. -

Social History

© University of London – Text by Dr Rosalind Johnson (edited by Mary Siraut) 1 SOCIAL HISTORY SOCIAL CHARACTER Although the medieval parish was dominated by the manor and the lord of the manor retained the advowson until the late 17th century, there is no evidence for a resident lord of the manor until the 1840s when Charles Noel Welman built Norton Manor.1 In 1700 the tenant at Knowle Hill had been able to fell a considerable amount of timber and establish a stone quarry before the lord was able to take any action.2 In 1327 Richard Stapeldon, lord of the manor, was assessed at 10s., substantially the largest assessment in the parish and only eight other taxpayers were assessed at 1s. or more, half of them in Langford.3 Fifteen persons with land or goods in Norton were assessed for the 1581 subsidy, though not all may have been resident. 4 In 1742 the parish was as assessed at 3s. 8d. as its proportion towards the county rate, an average figure for the parishes in the hundred of Taunton and Taunton Deane.5 By 1782 William Hawker, lord of the manor, was the chief landowner in the village, but there were several smaller estates and a number of small freeholders with a single dwelling or plot of land.6 Not until c.1842, There may have been tensions in the parish between more prosperous householders and the labouring classes. In 1849 concerns were expressed about the ‘excess and immorality’ in the village occasioned by labourers frequenting beer houses.7 In 1855 the vestry meeting agreed to offer a reward for information leading to a conviction after a spate of burglaries in the parish.8 1 See landownership. -

Somersetshire

400 TAUNTON. SOMERSETSHIRE. [ KELLY's Halse, Ham, Hatch Beauchamp, Heathfield, Henlade, Prince Albert's Somersetshire Light Infantry Regiment, Huish Cha.mpflower, Kingston, Langford, Lillesdon, 4th Battalion (2nd Somerset Militia); head quarters, Lydeard St. Lawrence, Milverton Na.ilesbourne, Barracks, Mount street; Hon. Col. W. Long, command Norton Fitzwarren, Newport, North Curry, Orchard ing; Hon. Lt.-Col. E. H. Llewellyn & C. S. Shepherd Portman, Otterford, Pitminster, Quantock, Ra.ddington, D.S.O. majors; Capt. E. A. B. Warry, instructor of Rowbarton, Ruishton, Staplegrove, Staple Fitzpaine, musketry; Capt. W. H. Lovett, adjutant; Lieut. li. Staplehay, Stoke St. Mary, Taunton, with Haydon, Powis, quartermaster Holway & Shoreditch, Thornfalcon, Thurlbear, Tul land, Trull, West Bagborough, West Hatch, West YEOMANRY CAVALRY. Monkton, Wilton, Wiveliscombe & Wrantage 4th Yeomanry Brigade. The Court has also Bankruptcy Jurisdiction & includes Brigade Office, Church square. for Bankruptcy purposes the following courts : Taunton, Officer Commanding Brigade, the Senior Commanding Williton, Chard & Wellington; George Philpott, Ham· met street, Taunton, official receiver Officer Certified Bailiffs under the " Law of Distress Amend Brigade Adjutant, Capt. Wilfred Edward Russell Collis West Somerset; depot, II Church square; Lieut.-Col. ment Act, 1888" : William James Villar, 10 Hammet Commanding, F. W. Forrester; H. T. Daniel, major ; street; Joseph Darby, 13 Hammet street; William Surgeon-Lieut.-Col. S. Farrant, medical officer • Waterman, 31 Paul street; Thomas David Woollen, Veterinary-Lieut. George Hill Elder M.R.C.V.S. Shire hall ; Howard Maynard, Hammet street ; John M. veterinary officer; Frederick Short, regimental sergt.- Chapman, 10 Canon street ; Horace White Goodman, • maJor 10 Hammet street; Frederick Williain Waterman, 31 B Squadron, Capt. E.