Racism in Antebellum Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

K:\Fm Andrew\21 to 30\27.Xml

TWENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1841, TO MARCH 3, 1843 FIRST SESSION—May 31, 1841, to September 13, 1841 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1841, to August 31, 1842 THIRD SESSION—December 5, 1842, to March 3, 1843 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1841, to March 15, 1841 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN TYLER, 1 of Virginia PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM R. KING, 2 of Alabama; SAMUEL L. SOUTHARD, 3 of New Jersey; WILLIE P. MANGUM, 4 of North Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKENS, 5 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—STEPHEN HAIGHT, of New York; EDWARD DYER, 6 of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JOHN WHITE, 7 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—HUGH A. GARLAND, of Virginia; MATTHEW ST. CLAIR CLARKE, 8 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—RODERICK DORSEY, of Maryland; ELEAZOR M. TOWNSEND, 9 of Connecticut DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH FOLLANSBEE, of Massachusetts ALABAMA Jabez W. Huntington, Norwich John Macpherson Berrien, Savannah SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE REPRESENTATIVES 12 William R. King, Selma Joseph Trumbull, Hartford Julius C. Alford, Lagrange 10 13 Clement C. Clay, Huntsville William W. Boardman, New Haven Edward J. Black, Jacksonboro Arthur P. Bagby, 11 Tuscaloosa William C. Dawson, 14 Greensboro Thomas W. Williams, New London 15 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas B. Osborne, Fairfield Walter T. Colquitt, Columbus Reuben Chapman, Somerville Eugenius A. Nisbet, 16 Macon Truman Smith, Litchfield 17 George S. Houston, Athens John H. Brockway, Ellington Mark A. Cooper, Columbus Dixon H. Lewis, Lowndesboro Thomas F. -

The Rise of Cornelius Peter Van Ness 1782- 18 26

PVHS Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society 1942 NEW SERIES' MARCH VOL. X No. I THE RISE OF CORNELIUS PETER VAN NESS 1782- 18 26 By T. D. SEYMOUR BASSETT Cornelius Peter Van Ness was a colorful and vigorous leader in a formative period of Vermont history, hut he has remained in the dusk of that history. In this paper Mr. Bassett has sought to recall __ mm and IUs activities and through him throw definite light on h4s --------- eventfultime.l.- -In--this--study Van--N-esr--ir-brought;-w--rlre-dt:a.mot~ months of his attempt in the senatorial election of I826 to succeed Horatio Seymour. 'Ulhen Mr. Bassett has completed his research into thot phase of the career of Van Ness, we hope to present the re sults in another paper. Further comment will he found in the Post script. Editor. NDIVIDUALISM is the boasted virtue of Vermonters. If they I are right in their boast, biographies of typical Vermonters should re veal what individualism has produced. Governor Van Ness was a typical Vermonter of the late nineteenth century, but out of harmony with the Vermont spirit of his day. This essay sketches his meteoric career in administrative, legislative and judicial office, and his control of Vermont federal and state patronage for a decade up to the turning point of his career, the senatorial campaign of 1826.1 His family had come to N ew York in the seventeenth century. 2 His father was by trade a wheelwright, strong-willed, with little book-learning. A Revolutionary colonel and a county judge, his purchase of Lindenwald, an estate at Kinderhook, twenty miles down the Hudson from Albany, marked his social and pecuniary success.s Cornelius was born at Lindenwald on January 26, 1782. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

H. Doc. 108-222

FOURTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1795, TO MARCH 3, 1797 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1795, to June 1, 1796 SECOND SESSION—December 5, 1796, to March 3, 1797 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—June 8, 1795, to June 26, 1795 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—JOHN ADAMS, of Massachusetts PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—HENRY TAZEWELL, 1 of Virginia; SAMUEL LIVERMORE, 2 of New Hampshire; WILLIAM BINGHAM, 3 of Pennsylvania SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JONATHAN DAYTON, 4 of New Jersey CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN BECKLEY, 5 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT GEORGIA Richard Potts 17 18 SENATORS SENATORS John Eager Howard Oliver Ellsworth 6 James Gunn REPRESENTATIVES James Hillhouse 7 James Jackson 14 8 Jonathan Trumbull George Walton 15 Gabriel Christie 9 Uriah Tracy Josiah Tattnall 16 Jeremiah Crabb 19 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 20 REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE William Craik Joshua Coit 21 Abraham Baldwin Gabriel Duvall Chauncey Goodrich Richard Sprigg, Jr. 22 Roger Griswold John Milledge George Dent James Hillhouse 10 James Davenport 11 KENTUCKY William Hindman Nathaniel Smith SENATORS Samuel Smith Zephaniah Swift John Brown Thomas Sprigg 12 Uriah Tracy Humphrey Marshall William Vans Murray Samuel Whittlesey Dana 13 REPRESENTATIVES DELAWARE Christopher Greenup MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Alexander D. Orr John Vining SENATORS Henry Latimer MARYLAND Caleb Strong 23 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE SENATORS Theodore Sedgwick 24 John Patten John Henry George Cabot 25 1 Elected December 7, 1795. -

“Blessings of Liberty” for All: Lysander Spooner's Originalism

SECURING THE “BLESSINGS OF LIBERTY” FOR ALL: LYSANDER SPOONER’S ORIGINALISM Helen J. Knowles* ABSTRACT On January 1, 1808, legislation made it illegal to import slaves into the United States.1 Eighteen days later, in Athol, Massachusetts, Ly- sander Spooner was born. In terms of their influence on the abolition of * Assistant Professor of Political Science, State University of New York at Oswego; B.A., Liverpool Hope University College; Ph.D., Boston University. This article draws on material from papers presented at the annual meetings of the Northeastern Political Science Association and the New England Historical Association, and builds on ideas originally discussed at the Institute for Constitutional Studies (ICS) Summer Seminar on Slavery and the Constitution and an Institute for Humane Studies An- nual Research Colloquium. For their input on my arguments about Lysander Spooner’s constitutional theory, I am grateful to Nigel Ashford, David Mayers, Jim Schmidt, and Mark Silverstein. Special thanks go to Randy Barnett who, several years ago, introduced me to Spooner, the “crusty old character” (as someone once described him to me) with whom I have since embarked on a fascinating historical journey into constitutional theory. I am also indebted to the ICS seminar participants (particularly Paul Finkelman, Maeva Marcus, and Mark Tushnet) for their comments and suggestions and to the participants in the Liberty Fund workshop on Lysander Spooner’s theories (particularly Michael Kent Curtis and Larry Solum) for prompting me to think about Spooner’s work in a variety of different ways. Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the American Antiquarian Society, the Rare Books Department of the Boston Public Library, and the Houghton Library and University Archives at Harvard University for their excellent research assistance. -

Twenty-Fifth Congress March 4, 1837, to March 3, 1839

TWENTY-FIFTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1837, TO MARCH 3, 1839 FIRST SESSION—September 4, 1837, to October 16, 1837 SECOND SESSION—December 4, 1837, to July 9, 1838 THIRD SESSION—December 3, 1838, to March 3, 1839 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1837, to March 10, 1837 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—RICHARD M. JOHNSON, 1 of Kentucky PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM R. KING, 2 of Alabama SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKENS, 3 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—JOHN SHACKFORD, of New Hampshire; STEPHEN HAIGHT, 4 of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JAMES K. POLK, 5 of Tennessee CLERK OF THE HOUSE—WALTER S. FRANKLIN, 6 of Pennsylvania; HUGH A. GARLAND, 7 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—RODERICK DORSEY, of Maryland DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—OVERTON CARR, of Maryland ALABAMA Samuel Ingham, Saybrook Jabez Y. Jackson, Clarkesville SENATORS Thomas T. Whittlesey, Danbury George W. Owens, Savannah William R. King, Selma Elisha Haley, Mystic George W. B. Towns, Talbotton John McKinley, 8 Florence Lancelot Phelps, Hitchcockville Clement C. Clay, 9 Huntsville Orrin Holt, Willington ILLINOIS REPRESENTATIVES SENATORS Reuben Chapman, Somerville DELAWARE John M. Robinson, Carmi Joshua L. Martin, Athens SENATORS Richard M. Young, Quincy 10 Joab Lawler, Mardisville Richard H. Bayard, Wilmington REPRESENTATIVES George W. Crabb, 11 Tuscaloosa Thomas Clayton, New Castle Adam W. Snyder, Belleville Dixon H. Lewis, Lowndesboro REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE Francis S. Lyon, Demopolis Zadoc Casey, Mount Vernon John J. Milligan, Wilmington William L. May, Springfield ARKANSAS SENATORS GEORGIA INDIANA William S. -

A House History

8 Center Street “THECORNERS” Siasconset A House History Written By Betsy Tyler Designed By Eileen Powers THE NANTUCKET PRESERVATION TRUST 2 Union Street Nantucket, Massachusetts www.nantucketpreservation.org Meerheim with new shingles,c.1889,painting by R.Way Smith Hannah B. Sharp 1885–1912 Dorothy Sharp Richmond 1912–1923 annah Sharp (1824–1912),widow of Benjamin Sharp of Philadelphia,occu- pied the house at 8 Center Street during the height of ’Sconset’sheyday as the meccaforasophisticatedbutfun-lovingsummercrowd,whohelpedtoestablish Hthe railroad, the Chapel, and the Casino.The popularity of the village led to real estate developmentnorthandsouthoftheoriginalfishinghamlet,andfilledthebighotelsand the little cottages with families from the major cities along the eastern seaboard. Hannah Sharp rented the cottage at 8 Center Street for the summer of 1885, and purchased it that September. Invitation to the hanging of the crane, 1885 Page from Meerheim guest book,1886 Hannah and her daughter, Mabel, named their cottage Meerheim, German for “ocean home,”and they kept a guest book in 1886 and 1887 that recorded visitors.The dedica- tion of Meerheim on June 28,1886,coincided with a meeting of the Nantucket Sorosis Club,aliteraryandphilosophicalsisterhoodwhoeducatedoneanotherwithdiscussions of literary topics.The Inquirer and Mirror reported the meeting: On Monday, June 28th, Sorosis was invited to meet with Mrs. Benjamin Sharp at her new cottage at Siasconset.Pleasant weather always lends inspiration to an out- of-town excursion,and this was one of the perfect days.So on the 10 o’clock train the happy band sped their way across the plain, by the placid sea, and were soon wel- comed by the kindly hostess within the cozy dwelling. -

H. Doc. 108-222

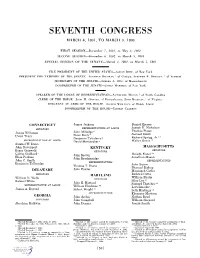

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913, Containing the Reminiscences of Harris Newmark

Sixty years in Southern California, 1853-1913, containing the reminiscences of Harris Newmark. Edited by Maurice H. Newmark; Marco R. Newmark HARRIS NEWMARK AET. LXXIX SIXTY YEARS IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA 1853-1913 CONTAINING THE REMINISCENCES OF HARRIS NEWMARK EDITED BY MAURICE H. NEWMARK MARCO R. NEWMARK Every generation enjoys the use of a vast hoard bequeathed to it by antiquity, and transmits that hoard, augmented by fresh acquisitions, to future ages. In these pursuits, therefore, the first speculators lie under great disadvantages, and, even when they fail, are entitled to praise.— MACAULAY. WITH 150 ILLUSTRATIONS Sixty years in Southern California, 1853-1913, containing the reminiscences of Harris Newmark. Edited by Maurice H. Newmark; Marco R. Newmark http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.023 NEW YORK THE KNICKERBOCKER PRESS 1916 Copyright, 1916 BY M. H. and M. R. NEWMARK v TO THE MEMORY OF MY WIFE v In Memoriam At the hour of high twelve on April the fourth, 1916, the sun shone into a room where lay the temporal abode, for eighty-one years and more, of the spirit of Harris Newmark. On his face still lingered that look of peace which betokens a life worthily used and gently relinquished. Many were the duties allotted him in his pilgrimage splendidly did he accomplish them! Providence permitted him the completion of his final task—a labor of love—but denied him the privilege of seeing it given to the community of his adoption. To him and to her, by whose side he sleeps, may it be both monument and epitaph. Thy will be done! M. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN Turnu I

[Vol.109 THE MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN TuRNu I "The Federalists have retired into the judiciary as a strong- hold . and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased." ' This bitter lament of Thomas Jefferson after he had succeeded to the Presidency referred to the final legacy bequeathed him by the Federalist party. Passed during the closing weeks of the Adams administration, the Judiciary Act of 1801 2 pro- vided the Chief Executive with an opportunity to fill new judicial offices carrying tenure for life before his authority ended on March 4, 1801. Because of the last-minute rush in accomplishing this purpose, those men then appointed have since been known by the familiar generic designation, "the midnight judges." This flight of Federalists into the sanctuary of an expanded federal judiciary was, of course, viewed by the Republicans as the last of many partisan outrages, and was to furnish the focus for Republican retaliation once the Jeffersonian Congress convened in the fall of 1801. That the Judiciary Act of 1801 was repealed and the new judges deprived of their new offices in the first of the party battles of the Jeffersonian period is well known. However, the circumstances surrounding the appointment of "the midnight judges" have never been recounted, and even the names of those appointed have vanished from studies of the period. It is the purpose of this Article to provide some further information about the final event of the Federalist decade. A cardinal feature of the Judiciary Act of 1801 was a reform long advocated-the reorganization of the circuit courts.' Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the judicial districts of the United States had been grouped into three circuits-Eastern, Middle, and Southern-in which circuit court was held by two justices of the Supreme Court (after 1793, by one justice) ' and the district judge of the district in which the court was sitting.5 The Act of 1801 grouped the districts t Assistant Professor of History, Wellesley College.