Eritrea Factsheet Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

Chad1 Djibouti Eritrea Ethiopia Kenya Somalia Sudan Uganda

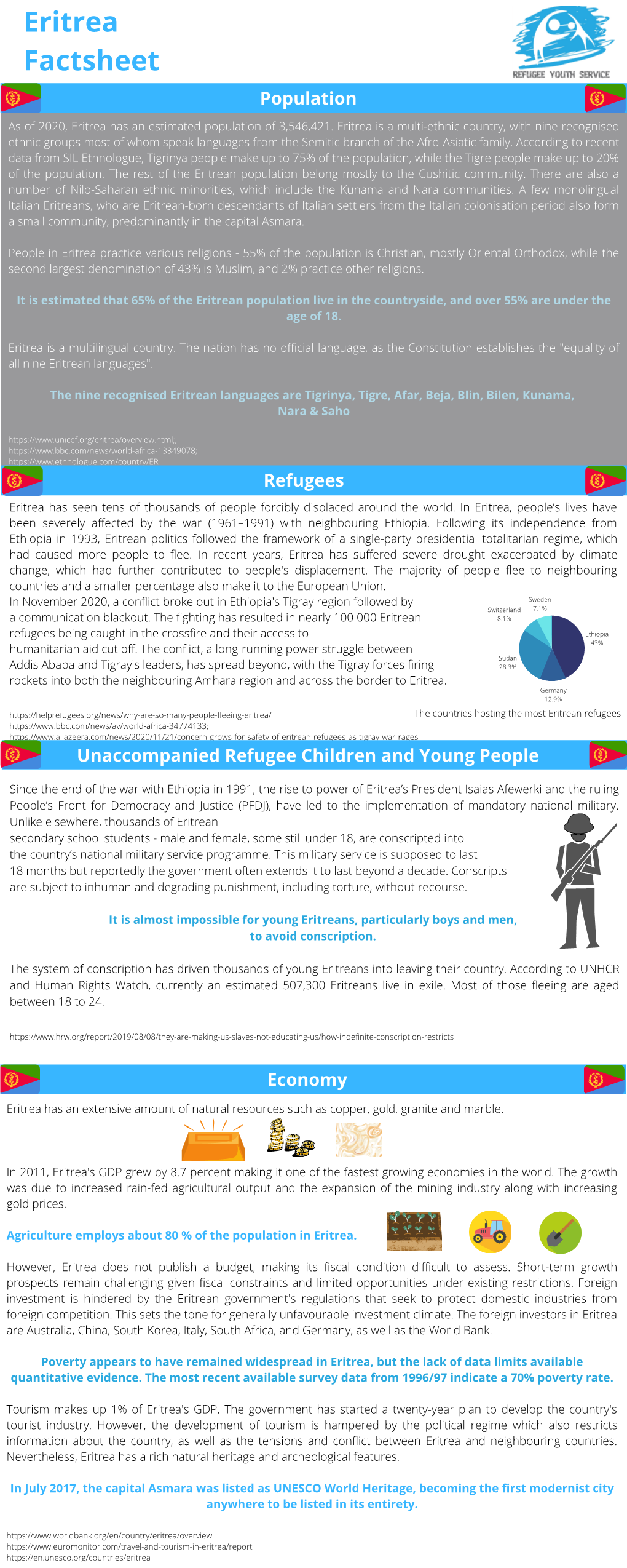

East and Hornof Africa Chad1 Djibouti Eritrea Ethiopia Kenya Somalia Sudan Uganda 1As of January 2011, Chad will be included in the East and Horn of Africa subregion. 58 UNHCR Global Appeal 2011 Update Refugees who have been displaced by the recent escalation in conflict in Somalia wait to be registered at Ifo camp in Kenya. Working environment The significant outflow of Eritreans into Ethiopia and Sudan—estimated at some 3,000 a month—continues to present The working environment in the East and Horn of Africa region, challenges. Moreover, Eritreans and Somalis en route to Europe including Chad and Sudan, continues to be influenced by the or the Middle East in growing mixed migration movements ever-deteriorating situation in Somalia, the ongoing population often fall victim to traffickers. movement from Eritrea and the uncertainty surrounding the outcome of the forthcoming referendum scheduled to take place Strategy in 2011 inSudaninJanuary2011. With armed groups in south and central Somalia becoming UNHCR will monitor early warning signs in order to adapt to increasingly radicalized and the Transitional Federal the changing environment, and will regularly update the Government in Mogadishu weakened by internal power contingency plans it has developed in 2010 for Somalia and struggles, no peaceful solution appears to be in sight for Somalia. Sudan. In Somalia, the Office will increase its presence in The bomb attacks in Kampala, Uganda, in July 2010, for which “Puntland” and “Somaliland” as well as the southern and the Al Shabaab militia has claimed responsibility,were intended to central parts of the country. Efforts to strictly monitor the use persuade the Ugandan Government to withdraw its troops from of humanitarian assistance in the Somalia context will Somalia. -

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration Andintegration

Post-Colonial Journeys: Historical Roots of Immigration andIntegration DYLAN RILEY AND REBECCA JEAN EMIGH* ABSTRACT The effect ofItalian colonialismon migration to Italy differedaccording to the pre-colonialsocial structure, afactor previouslyneglected byimmigration theories. In Eritrea,pre- colonialChristianity, sharp class distinctions,and a strong state promotedinteraction between colonizers andcolonized. Eritrean nationalismemerged against Ethiopia; thus, nosharp breakbetween Eritreans andItalians emerged.Two outgrowths ofcolonialism, the Eritrean nationalmovement andreligious ties,facilitate immigration and integration. In contrast, in Somalia,there was nostrong state, few class differences, the dominantreligion was Islam, andnationalists opposed Italian rule.Consequently, Somali developed few institutionalties to colonialauthorities and few institutionsprovided resources to immigrants.Thus, Somaliimmigrants are few andare not well integratedinto Italian society. * Direct allcorrespondence to Rebecca Jean Emigh, Department ofSociology, 264 HainesHall, Box 951551,Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551;e-mail: [email protected]. ucla.edu.We would like to thank Caroline Brettell, RogerWaldinger, and Roy Pateman for their helpfulcomments. ChaseLangford made the map.A versionof this paperwas presentedat the Tenth International Conference ofEuropeanists,March 1996.Grants from the Center forGerman andEuropean Studies at the University ofCalifornia,Berkeley and the UCLA FacultySenate supported this research. ComparativeSociology, Volume 1,issue 2 -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Mixed Migration in the Horn of Africa and Yemen

MIXED MIGRATION Member agency data inventory (2-4 pages max) SuggestedIN HORN ‘template’ approach: OF AFRICA AND YEMEN Reflection:October Identify 2012the key areas of expertise that your agency specifically deals with that intersect with mixed migration issues. (if you need to be sure about mixed migration go to www.regionalmms.com to learn more) Egypt 'Secondary movement': Some migrants go through the Gulf into the Middle East and Europe, working along the way. If they can afford it Saudi Arabia: Saudi Arabia appears to have an Towards Egypt: Eritreans, Somalis and Ethiopians and have sufficient contacts / documentation migrants always prefer to ambivalent attitude to irregular migrants. While it (and other migrants) use the 'northern' route into fly. claims to be intolerant and strict, officially, in practice, Egypt where Cairo is a destination or a transit point many thousands of Ethiopians, Somalis, Kenyans and to pass into the Sinai region and into Israel. During others live and work in Saudi Arabia. Yemenis also the month of October security forces in Egypt Saudia Arabia Abuse: Most of the Ethiopians cross into KSA irregularly in large numbers. Many arrested 10 undocumented African migrants who arriving in Yemen are enroute migrants (economic) are detained and deported back were trying to enter Israel illegally through the Sinai to Saudi Arabia. They normally into Yemen. border. travel along the eastern side with smugglers (benign or violent) up to Haradh area in order to cross into KSA. The Trafficking of women: . incidences of kidnapping, There are reports of torture, rape and extorion of women being separated Red Sea new arrivals is very high. -

Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War Sandra F

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2000 Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War Sandra F. Joireman University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Joireman, Sandra F. "Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War." In History Behind the Headlines: The Origins of Conflicts Worldwide, edited by Sonia G. Benson, Nancy Matuszak, and Meghan Appel O'Meara, 1-11. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War History Behind the Headlines, 2001 The Conflict The war between Ethiopia and Eritrea—two of the poorest countries in the world— began in 1998. Eritrea was once part of the Ethiopian empire, but it was colonized by Italy from 1869 to 1941. Following Italy's defeat in World War II, the United Nations determined that Eritrea would become part of Ethiopia, though Eritrea would maintain a great deal of autonomy. In 1961 Ethiopia removed Eritrea's independence, and Eritrea became just another Ethiopian province. In 1991 following a revolution in Ethiopia, Eritrea gained its independence. However, the borders between Ethiopia and Eritrea had never been clearly marked. -

Djibouti–Eritrea Background

1 Djibouti–Eritrea Background: A crisis occurred between Djibouti and Eritrea over the disputed border region of Ras Doumeira from 7 April to the end of June 2008. Djibouti and Eritrea share a border of 110 km which was initially drawn by Italy and France in 1900, following a dispute in 1898. Although Djibouti and Eritrea had a skirmish and a two-month standoff in 1996, the relations between the two had improved after 2000. More than 1,200 US troops and 2,850 French troops are stationed in Djibouti. Eritrea also has an unresolved border conflict with Ethiopia that has resulted in three crises (cases #424, #446, and #456) since 1998. PRE-CRISIS: According to a Djiboutian report, Eritrea started to deploy military equipment in their common border region in early 2008, in the name of road construction. Summary: The crisis began on 7 April 2008 when Eritrean armed forces penetrated into Djiboutian territory, dug trenches on both sides of the border, and occupied Ras-Doumeira. This triggered a crisis for Djibouti. Eritrea denied the charge. The Djiboutian army made a request to probe the situation, which Eritrea also denied. From 7 to 22 April, the two sides pursued negotiations. This also constituted Djibouti’s major response to the crisis trigger. Several rounds of futile negotiations followed. Presidents Isaias Afwerki of Ethiopia and Ismaïl Omar Guelleh of Djibouti were involved in these efforts. On 22 April, Djibouti sent its troops to the border area, and negotiations between the two sides ceased. On 5 May, Djibouti took the case to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), the African Union (AU), and the Arab League, all of which urged Djibouti and Eritrea to exercise restraint. -

The Ethio-Eritrea Common Market (1991 to 1998)

Asymmetric Benefits: The Ethio-Eritrea Common Market (1991-1998) Worku Aberra, Dawson College, Westmount, Quebec Abstract Economic theory suggests that a common market between two or more countries improves overall well-being, but it creates winners and losers in each country. Recent empirical findings also show that the overall impact of a common market on per capita income depends on the similarity of economic development between member countries. A common market among developed countries results in the convergence of per capita income while a common market among developing countries results in the divergence of per capita income. The difference in outcome, some economists suggest, is due to variations in comparative advantage between member states and the rest of the world. But the theory of comparative advantage does not fully explain the results of the de facto common market between Ethiopia and Eritrea (1991-1998). The empirical findings of this study demonstrate that the Ethio-Eritrea preferential trade arrangement benefited Eritrea and harmed Ethiopia. The main reason for these asymmetric consequences was acceptance by the Ethiopian government of the unfavourable terms of the preferential trade arrangement between the two countries. Background Economic theory suggests that a common market between two or more countries improves overall well-being, but such a market also creates winners and losers in each country because of the flow of capital, labor, goods, and services across the member countries (Venables, 2016). When capital flows from countries with a low rate of profit (capital-abundant countries) to countries with a high rate of profit (capital-poor countries), it reduces the difference in the rate of profit, and owners of capital in countries with a high rate of profit lose while owners of capital in countries with a low rate of profit gain. -

Racial and Ethnic Discourses Within Seattle's Habesha Community

Re-Imagining Identities: Racial and Ethnic Discourses within Seattle’s Habesha Community Azeb Madebo Abstract My research explores the means by which identities of “non- white” Habesha (Ethiopian and Eritrean) immigrants are negotiated through the use of media, community spaces, collectivism, and activism. As subjects who do not have a longstanding historical past in the United States, Ethiopian/Eritrean immigrants face the challenges of having to re-construct and negotiate their identities within American binary Black/White racial landscapes. To explore the ways in which ethnicity- based collectivism and activism challenge stereotypical portrayals of Habeshaness and Blackness which are typically cemented through media, I focus on unpacking mediated representations of Hana Alemu Williams, her death, trial, and subsequent support from the Ethiopian Community of Seattle (ECS). Hana Alemu Williams was an Ethiopian child who died in 2011 from abuse, severe malnutrition, and cruelty at the hands of her White adoptive family in Sedro-Woolley Washington. Through close readings of various media: news paper articles, television news broadcastings, and blogs, I critically analyze the moments in which Habesha immigrants challenge narratives of race and identity in the American context. I find that while Ethiopian/Eritrean immigrants sometimes assimilate into American constructions of race, at other moments they create counter-narratives of hybridity, exclusive ethnic identities, or maintain purely national identities as Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants, in an effort to defer perceived racial stereotypes and oppression that arise from identifying with an undifferentiated Black identity. This research enriches existing academic literature by creating a more nuanced understanding of Seattle Habesha community racial and ethnic discourses in their efforts to re-imagine Habesha identities. -

Positioning Eritrea T

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND BUSINESS DELIVERY OFFICE, EAST AFRICA (RDGE) Khushee Tower, Longonot Road, Upper Hill P. O. Box 4861 - 00200, Nairobi, Kenya.tel: (+254-20) 2998352 Fax: (+254-20) 271 2938 Website: www.afdb.org; E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected]. Brief Description of the assignment; POSITIONING ERITREA’S FINANCIAL SECTOR TO INCREASE ACCESS TO CREDIT FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES Place of assignment: Asmara, Eritrea and partly virtual Period of assignment: December 2020 – June 2021 Expected start date of the assignment: December 2020 Last date for expressing interest: 4th December 2020 Expression of interest to be submitted to: [email protected] and copy [email protected] Any questions/ clarifications needed to be addressed to: [email protected] and [email protected] Further details are as below. TERMS OF REFERENCE POSITIONING ERITREA’S FINANCIAL SECTOR TO INCREASE ACCESS TO CREDIT FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES GENERAL INFORMATION Services/Work Description: Conduct a diagnostic study to (a) assess the impact of COVID-19 on Eritrea’s financial sector (b) assess the capacity of the Eritrean Investment and Development Bank (EIDB) to provide credit to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and (c) develop a road map for financial sector development and proposal to strengthen the banking sector in general and EIDB in particular. Type of the Contract: Individual Consultants Expected Duration: Six (6) person months: December 2020 – June 2021 Expected Start Date: December 2020 I. Background Update on recent economic developments Eritrea remains trapped in a low and volatile growth situation resulting in pervasive poverty. -

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

SIPRI Background Paper April 2019 THE FOREIGN MILITARY SUMMARY w The Horn of Africa is PRESENCE IN THE HORN OF undergoing far-reaching changes in its external security AFRICA REGION environment. A wide variety of international security actors— from Europe, the United States, neil melvin the Middle East, the Gulf, and Asia—are currently operating I. Introduction in the region. As a result, the Horn of Africa has experienced The Horn of Africa region has experienced a substantial increase in the a proliferation of foreign number and size of foreign military deployments since 2001, especially in the military bases and a build-up of 1 past decade (see annexes 1 and 2 for an overview). A wide range of regional naval forces. The external and international security actors are currently operating in the Horn and the militarization of the Horn poses foreign military installations include land-based facilities (e.g. bases, ports, major questions for the future airstrips, training camps, semi-permanent facilities and logistics hubs) and security and stability of the naval forces on permanent or regular deployment.2 The most visible aspect region. of this presence is the proliferation of military facilities in littoral areas along This SIPRI Background the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.3 However, there has also been a build-up Paper is the first of three papers of naval forces, notably around the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, at the entrance to devoted to the new external the Red Sea and in the Gulf of Aden. security politics of the Horn of This SIPRI Background Paper maps the foreign military presence in the Africa. -

Eritreans in Egypt at Risk of Forcible Return

UA: 321/11 Index: MDE 12/055/2011 Egypt Date: 2 November 2011 URGENT ACTION ERITREANS IN EGYPT AT RISK OF FORCIBLE RETURN A group of 118 male asylum-seekers face imminent forcible return from Egypt to Eritrea, where they would be at grave risk of torture and arbitrary detention. After being arrested and detained in and around the city of Aswan, southern Egypt, 118 male Eritrean asylum- seekers have been recently transferred to a compound in Shallal, a town south of the city. Security forces have reportedly beaten some detainees, including on the legs and head, to force them to fill in papers provided by Eritrean diplomatic representatives to arrange their deportation. The reported involvement of Eritrean government representatives in documenting the detainees increases the likelihood that the group will be at risk if returned. Amnesty International considers that there is a significant risk that if the group is forcibly returned to Eritrea they will be tortured or otherwise ill-treated and detained without charge or trial in appalling conditions. Eritrean nationals forcibly returned to Eritrea have been detained incommunicado and tortured upon return, particularly those who had fled the country to avoid conscription. Large numbers of those detained in Shallal are reported to be young adults of national service age, many of whom fled Eritrea to escape military service. As in previous cases documented by Amnesty International in recent years, despite requesting it, none of the Eritrean asylum-seekers has been allowed access to representatives from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Cairo. Amnesty International is concerned at increased reports of forcible returns of Eritrean nationals in recent weeks, as well as reports that further groups of Eritreans in detention are at risk of forcible removal to Eritrea.