Ethiopia Eritrea Somalia Djibouti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

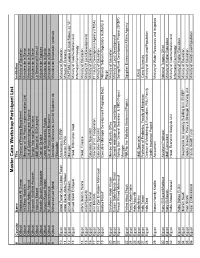

Cairo Workshop Participants

Master Cairo Workshop Participant List # Country Name Title Institution 1 Djibouti Abdourazak Ali Osman Director of Planning Department Ministry of Education 2 Djibouti Ali Sillaye Abdallah Manager of the Project Implementation Unit Ministere de la Sante 3 Djibouti Ammar Abdou Ahmed Dri. of Epidemiology and Hygiene Ministere de la Sante 4 Djibouti Assoweh Abdillahi Assoweh Service Information Sanitaire Ministere de la Sante 5 Djibouti Fatouma Bakard M&E Specialist, SIDA project Le Secretariat Executif 6 Djibouti Housein Doualeh Aboubaker Chef de Service Ministere de Finances 7 Djibouti Hussein Kayad Halane Unite de Gestion de Projets Ministere de la Sante 8 Djibouti M. Abdelrahmane Dir. of Planning and Research Ministere de la Sante 9 Djibouti Mohamed Issé Mahdi Secrétaire Générale du Comité Supérieur de Ministère de l'éducation nationale l'Education 10 Egypt Abdel Fattah Samir Abdel Fattah Accountant, ECEEP Ministry of Education 11 Egypt Abdel Samie Abdel Hafeez Director PPMU Ministry of Economy 12 Egypt Ahmed Abdel Monem Manager PAPFAM, League of Arab States, 22 "A" 13 Egypt Ahmed Saad El Sayed Head, Information Dept. Ministry of Communication and InformationTechnology: 14 Egypt Alfons Ibrahim Hanna Head, Finance Ministry of Education 15 Egypt Amal Sayed Ali Ministry Of Local Development 16 Egypt Amany Kamel Education Specialist Ministry of Education 17 Egypt Amr Mostafa Director of Int. Cooperation IT Industry Development Agency (ITIDA) 18 Egypt Amr Zein El-Abdein Mahmoud Education Specialist Ministry of Education 19 Egypt Bodour Nassif Executive Manager Development Programs Dept. National Telecom Regulatory Authority in Egypt 20 Egypt Ebraheem Abdel Khalek Member of Quality Office Ministry of Education 21 Egypt Essam Galal Hassan Shaat General manager of local monitoring Ministry of Local Development 22 Egypt Farouk Ahmed Mahmoud Sohag Gov. -

Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa

Natural Disasters in Public Disclosure Authorized the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2014 Urban, Social Development, and Disaster Risk Management Unit Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundar- ies, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Recon- struction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Djibouti Bishop Happy That Mogadishu Cathedral Ruins Are Helping Somalis

Djibouti bishop happy that Mogadishu cathedral ruins are helping Somalis NAIROBI, Kenya – Djibouti Bishop Giorgio Bertin, who oversees Catholics in neighboring Somalia, said he is happy that the ruins of Mogadishu’s only Catholic cathedral are housing hundreds of displaced Somalis. “In Mogadishu there are hundreds of camps for displaced people. The cathedral area is one of them,” the bishop said in an email interview. “I think that at least 300 could easily fit in, but I have no real figures.” The U.N. officially has declared a famine in parts of Somalia, including the internally displaced communities in Mogadishu, the Somali capital. More than 100,000 Somalis poured into the capital searching for food within a two-month period this summer. Somalia has had a civil war since 1991, and the famine-hit areas are plagued by a lack of security because of a weak central government and the presence of various political factions that control parts of the country. The instability and resulting violence severely limit the delivery of humanitarian assistance. Hundreds of thousands of Somalis have fled to Kenya. Bishop Bertin said the best solution would be to help the displaced people within Somalia, “but the problem is often that where they are either they are unsafe or we cannot reach them.” In 1989, Italian-born Bishop Pietro Salvatore Colombo of Mogadishu was killed at his cathedral. After the murder, the Vatican eliminated the post and now oversees Somalia through neighboring Djibouti. “The cathedral has not been used since Jan. 9, 1991, when it was ransacked” and set on fire, said Bishop Bertin. -

S/2003/223 Security Council

United Nations S/2003/223 Security Council Distr.: General 25 March 2003 Original: English Letter dated 25 March 2003 from the Chairman of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia, and in accordance with paragraph 11 of Security Council resolution 1425 (2002), I have the honour to transmit herewith the report of the Panel of Experts mandated to collect independent information on violations of the arms embargo on Somalia and to provide recommendations on possible practical steps and measures for implementing it. In this connection, the Committee would appreciate it if this letter together with its enclosure were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Stefan Tafrov Chairman Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia 03-25925 (E) 210303 *0325925* S/2003/223 Letter dated 24 February 2003 from the Panel of Experts to the Chairman of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia We have the honour to enclose the report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia, in accordance with paragraph 11 of Security Council resolution 1425 (2002). (Signed) Ernst Jan Hogendoorn (Signed) Mohamed Abdoulaye M’Backe (Signed) Brynjulf Mugaas 2 S/2003/223 Report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia pursuant to Security Council resolution 1425 (2002) Contents Paragraphs Page Abbreviations ................................................................. 5 Summary ..................................................................... 6 Introduction ......................................................... 1–13 11 Background to the current instability in Somalia .......................... -

African Newspapers: the British Library Collection from Culture to History to Geopolitics

African Newspapers: The British Library Collection From culture to history to geopolitics Quick Facts A unique database of 19th-century African newspapers offering all-new coverage Created in partnership with the British Library and its world-renowned curators An invaluable historical record for students and scholars in dozens of academic disciplines Overview African Newspapers: The British Library Collection features 64 newspapers from across the African continent, all published before 1900. Originally archived by the British Library—the national library of the United Kingdom and one of the largest and most respected libraries in the world—these rare historical documents are now available for the first time in a fully searchable online collection. From culture to history to geopolitics, the pages of these newspapers offer fresh research opportunities for students and scholars interested in topics related to Africa. An unmatched chronicle of African history Because Africa produced comparatively few newspapers in the 19th century, each page in this collection is significant, offering invaluable insight into the people, issues and events that shaped the continent. Through eyewitness reporting, editorials, letters, advertisements. obituaries and military reports, the newspapers in this one-of-a-kind collection chronicle African history and daily life as never before. Students and researchers will find news and analysis covering the European exploration of Africa, colonial exploitation, economics, Atlantic trade, the mapping of the continent, early moves towards self-governance, the growth of South Africa and much more. Created in partnership with the British Library The British Library’s incomparable collection of African newspapers is the result of the close and often controversial relationships between Great Britain and African nations during the period of colonial rule. -

HIV in the Middle East and North Africa 2013 - 2015

HIV in the Middle East and North Africa 2013 - 2015 Together for a Fast-Track Response UNAIDS Regional Support Team for the Middle East & North Africa Abdoul Razzak El-Sanhouri Street, 20 Nasr City Cairo, Egypt Tel: (+20) 222765257 Executive Summary some countries, stabilising in others, and increasing in a few. Similarly with AIDS deaths, the The HIV Epidemic in MENA regional total by 2014 has increased from 7500 in 2005 to 12,000, with 90 The UNAIDS Middle East and North per cent of these occurring in five Africa (MENA) region includes 21 countries (Iran, Sudan, Somalia, countries1 that are home to 445 Morocco and Djibouti). Some million people. The region has one countries have seen doubling and of the youngest populations in even tripling of the number of the world, with around 300 million estimated AIDS deaths in the past people aged 15-39, of whom 42 ten years, while in others it has million are aged between 15 and 19 decreased. years old. Significant numbers of people in The region represents wide diversity the region are still left behind in in terms of social and economic terms of treatment and prevention. development and political stability. In too many countries, stigma, MENA is also the setting for several discrimination and human rights humanitarian crises, both recent violations constitute significant and protracted, the repercussions barriers to progress. of which have been felt throughout the region in terms of massive displacement of people, within and between countries, and the Political, policy and consequent strains on resources programmatic achievements and services. -

Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War Sandra F

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Political Science Faculty Publications Political Science 2000 Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War Sandra F. Joireman University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/polisci-faculty-publications Part of the African Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Joireman, Sandra F. "Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War." In History Behind the Headlines: The Origins of Conflicts Worldwide, edited by Sonia G. Benson, Nancy Matuszak, and Meghan Appel O'Meara, 1-11. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale Group, 2001. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethiopia and Eritrea: Border War History Behind the Headlines, 2001 The Conflict The war between Ethiopia and Eritrea—two of the poorest countries in the world— began in 1998. Eritrea was once part of the Ethiopian empire, but it was colonized by Italy from 1869 to 1941. Following Italy's defeat in World War II, the United Nations determined that Eritrea would become part of Ethiopia, though Eritrea would maintain a great deal of autonomy. In 1961 Ethiopia removed Eritrea's independence, and Eritrea became just another Ethiopian province. In 1991 following a revolution in Ethiopia, Eritrea gained its independence. However, the borders between Ethiopia and Eritrea had never been clearly marked. -

Transcript of Oral History Interview with Ali K. Galaydh

Ali Khalif Galaydh Narrator Ahmed Ismail Yusuf Interviewer February 10, 2014 Shoreview, Minnesota Ali Khalif Galaydh -AG Ahmed Ismail Yusuf -AY AY: I am Ahmed Ismail Yusuf. This is an interview for the Minnesota Historical Society Somali Oral History Project. I am with Ali Khalif Galaydh. We are in Shoreview, Minnesota. It is February 10, 2014. Ali Khalif Galaydh is a talented Somali politician, educator on a professorial level, and at times even a businessman. As a professor he taught at the Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota and the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. He was a fellow at Weatherhead Center of International Affairs and Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. In Somalia he had several titles, but the highest office was when he became the fourth-ever Somali prime minister in 2000. In Somali circles Ali is also known for his intellectual prowess and political versatility. Ali, welcome to the interview—third time again. AG: Thank you very much, Ahmed. AY: Okay, I want to start from where were you born and when were you born, even though we don’t actually acknowledge that at all. AG: Somalis normally don’t celebrate birthdays, so there is now quite an always heated discussion about who is older than who. But in my case, my father was in the British Merchant Marine, and he therefore recorded when I was born. There was no birth certificate, but I was born October 15, 1941. AY: Wow, so you do have the recorded date, at least. -

SOMALIË Veiligheidssituatie in Somaliland En Puntland

COMMISSARIAAT-GENERAAL VOOR DE VLUCHTELINGEN EN DE STAATLOZEN COI Focus SOMALIË Veiligheidssituatie in Somaliland en Puntland 30 juni 2020 (update) Cedoca Oorspronkelijke taal: Nederlands DISCLAIMER: Dit COI-product is geschreven door de documentatie- en researchdienst This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and Cedoca van het CGVS en geeft informatie voor de behandeling van Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the individuele verzoeken om internationale bescherming. Het document bevat processing of individual applications for international protection. The geen beleidsrichtlijnen of opinies en oordeelt niet over de waarde van het document does not contain policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass verzoek om internationale bescherming. Het volgt de richtlijnen van de judgment on the merits of the application for international protection. It follows Europese Unie voor de behandeling van informatie over herkomstlanden van the Common EU Guidelines for processing country of origin information (April april 2008 en is opgesteld conform de van kracht zijnde wettelijke bepalingen. 2008) and is written in accordance with the statutory legal provisions. De auteur heeft de tekst gebaseerd op een zo ruim mogelijk aanbod aan The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected zorgvuldig geselecteerde publieke informatie en heeft de bronnen aan elkaar with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even getoetst. Het document probeert alle relevante aspecten van het onderwerp though the document tries to cover all the relevant aspects of the subject, the te behandelen, maar is niet noodzakelijk exhaustief. Als bepaalde text is not necessarily exhaustive. -

Djibouti–Eritrea Background

1 Djibouti–Eritrea Background: A crisis occurred between Djibouti and Eritrea over the disputed border region of Ras Doumeira from 7 April to the end of June 2008. Djibouti and Eritrea share a border of 110 km which was initially drawn by Italy and France in 1900, following a dispute in 1898. Although Djibouti and Eritrea had a skirmish and a two-month standoff in 1996, the relations between the two had improved after 2000. More than 1,200 US troops and 2,850 French troops are stationed in Djibouti. Eritrea also has an unresolved border conflict with Ethiopia that has resulted in three crises (cases #424, #446, and #456) since 1998. PRE-CRISIS: According to a Djiboutian report, Eritrea started to deploy military equipment in their common border region in early 2008, in the name of road construction. Summary: The crisis began on 7 April 2008 when Eritrean armed forces penetrated into Djiboutian territory, dug trenches on both sides of the border, and occupied Ras-Doumeira. This triggered a crisis for Djibouti. Eritrea denied the charge. The Djiboutian army made a request to probe the situation, which Eritrea also denied. From 7 to 22 April, the two sides pursued negotiations. This also constituted Djibouti’s major response to the crisis trigger. Several rounds of futile negotiations followed. Presidents Isaias Afwerki of Ethiopia and Ismaïl Omar Guelleh of Djibouti were involved in these efforts. On 22 April, Djibouti sent its troops to the border area, and negotiations between the two sides ceased. On 5 May, Djibouti took the case to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), the African Union (AU), and the Arab League, all of which urged Djibouti and Eritrea to exercise restraint. -

Positioning Eritrea T

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND BUSINESS DELIVERY OFFICE, EAST AFRICA (RDGE) Khushee Tower, Longonot Road, Upper Hill P. O. Box 4861 - 00200, Nairobi, Kenya.tel: (+254-20) 2998352 Fax: (+254-20) 271 2938 Website: www.afdb.org; E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected]. Brief Description of the assignment; POSITIONING ERITREA’S FINANCIAL SECTOR TO INCREASE ACCESS TO CREDIT FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES Place of assignment: Asmara, Eritrea and partly virtual Period of assignment: December 2020 – June 2021 Expected start date of the assignment: December 2020 Last date for expressing interest: 4th December 2020 Expression of interest to be submitted to: [email protected] and copy [email protected] Any questions/ clarifications needed to be addressed to: [email protected] and [email protected] Further details are as below. TERMS OF REFERENCE POSITIONING ERITREA’S FINANCIAL SECTOR TO INCREASE ACCESS TO CREDIT FOR MICRO, SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES GENERAL INFORMATION Services/Work Description: Conduct a diagnostic study to (a) assess the impact of COVID-19 on Eritrea’s financial sector (b) assess the capacity of the Eritrean Investment and Development Bank (EIDB) to provide credit to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and (c) develop a road map for financial sector development and proposal to strengthen the banking sector in general and EIDB in particular. Type of the Contract: Individual Consultants Expected Duration: Six (6) person months: December 2020 – June 2021 Expected Start Date: December 2020 I. Background Update on recent economic developments Eritrea remains trapped in a low and volatile growth situation resulting in pervasive poverty.