Intercontinental Relations in a Multipolar World and the Way Ahead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Kapal Dan Perahu Dalam Hikayat Raja Banjar: Kajian Semantik (Ships and Boats in the Story of King Banjar: Semantic Studies)

Borneo Research Journal, Volume 5, December 2011, 187-200 KAPAL DAN PERAHU DALAM HIKAYAT RAJA BANJAR: KAJIAN SEMANTIK (SHIPS AND BOATS IN THE STORY OF KING BANJAR: SEMANTIC STUDIES) M. Rafiek Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia, Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan, Universitas Lambung Mangkurat, Banjarmasin, Indonesia ([email protected]) Abstract Ships and boats are water transportation has long been used by the public. Ships and boats also fabled existence in classical Malay texts. Many types of ships and boats were told in classical Malay texts are mainly in the Story of King Banjar. This study aimed to describe and explain the ships and boats in the Story of King Banjar with semantic study. The theory used in this research is the theory of change in the region meaning of Ullmann. This paper will discuss the discovery of the types of ships and boats in the text of the King saga Banjar, the ketch, ship, selup, konting, pencalang, galleon, pelang, top, boat, canoe, frigate, galley, gurab, galiot, pilau, sum, junk, malangbang, barge, talamba, lambu, benawa, gusu boat or bergiwas awning, talangkasan boat and benawa gurap. In addition, it was also discovered that the word ship has a broader meaning than the words of other vessel types. Keywords: ship, boat, the story of king banjar & meaning Pendahuluan Hikayat Raja Banjar atau lebih dikenal dengan Hikayat Banjar merupakan karya sastra sejarah yang berasal dari Kalimantan Selatan. Hikayat Raja Banjar menjadi sangat dikenal di dunia karena sudah diteliti oleh dua orang pakar dari Belanda, yaitu Cense (1928) dan Ras (1968) menjadi disertasi. -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

The Struggle for Worker Rights in EGYPT AREPORTBYTHESOLIDARITYCENTER

67261_SC_S3_R1_Layout 1 2/5/10 6:58 AM Page 1 I JUSTICE I JUSTICE for ALL for I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I “This timely and important report about the recent wave of labor unrest in Egypt, the country’s largest social movement ALL The Struggle in more than half a century, is essential reading for academics, activists, and policy makers. It identifies the political and economic motivations behind—and the legal system that enables—the government’s suppression of worker rights, in a well-edited review of the country’s 100-year history of labor activism.” The Struggle for Worker Rights Sarah Leah Whitson Director, Middle East and North Africa Division, Human Rights Watch I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I for “This is by far the most comprehensive and detailed account available in English of the situation of Egypt’s working people Worker Rights today, and of their struggles—often against great odds—for a better life. Author Joel Beinin recounts the long history of IN EGYPT labor activism in Egypt, including lively accounts of the many strikes waged by Egyptian workers since 2004 against declining real wages, oppressive working conditions, and violations of their legal rights, and he also surveys the plight of A REPORT BY THE SOLIDARITY CENTER women workers, child labor and Egyptian migrant workers abroad. -

Chinese and Swiss Perspectives

101 8 How to understand the peacebuilding potential of the Belt and Road Initiative Dongyan Li Introduction In his keynote speech at the Belt and Road International Forum in May 2017, President Xi Jinping proposed to build the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into a “road for peace”. The World Bank and the United Nations also put forward a joint report on the Pathways for Peace in 2018, and emphasized that violence and conflict are big obstacles to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. Their report argues that conflict prevention is a decisive factor for develop ment and economic cooperation, and indeed central to reducing pov erty and achieving shared prosperity (World Bank and United Nations). This report reflects an increasing trend to strengthen the interaction between the peace and development agendas, and to promote cooper ation between both sets of actors. In this context, this chapter explores the peacebuilding potential of BRI and how to understand the possible connection between BRI and UN peacebuilding. BRI has peacebuilding potential in many aspects, but these potentials are limited at the current stage and uncertain in the future. International efforts are a necessary condition for promoting BRI to contribute more to peacebuilding. The chapter consists of three main sections. First, it explains the core of BRI, which is an economic cooperation– focused initiative, not a peacebuilding initiative; second, it interprets the peace connection and peacebuilding potential of BRI; third, it analyzes the limitations and uncertainties of the peacebuilding potential of BRI, and tries to predict the possible scenarios. The Belt and Road: an economic cooperation initiative There are different interpretations and expectations for BRI both inter nationally and domestically. -

Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Navies and Soft Power: Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force, edited by Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, as an official publica tion of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-00001 ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4; e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1 Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force Bruce A. -

A History of the Independent African Colonization Movement in Pennsylvania

Kurt Lee Kocher A DUTY TO AMERICA AND AFRICA: A HISTORY OF THE INDEPENDENT AFRICAN COLONIZATION MOVEMENT IN PENNSYLVANIA ".. with the success of the colonization cause is intimately con- nected the perpetuity of the union of those States, the happiness of the people of this country, the elevation of the colored population to the enjoyment of rational and civil liberty, and the civilization of Africa and her conversion to Christianity. , Rev. George M. Bethune Philadelphia In furthering the great scheme of civilization there [in Africa] where it is so much needed, we redeem in part the discredit which every descendant from a European stock inherits in his paternal share of the fatal wrongs inflicted through a long course of years upon that benighted and injured land. Address of Joseph R. Ingersoll at the Annual Meeting of the Pennsylvania Colonization Society October 25, 1838 THE African colonization movement of the nineteenth century remains an enigma. The difficulty in discussing colonization centers primarily on whether it was an attempt to "civilize" Africa and rid the nation of slavery, or was an attempt by white America to achieve a racially pure nation. Efforts to answer this question are complicated by the fact that the early nineteenth century was a period of widespread religious ferment and deep conviction. When religion is added to any 118 AFRICAN COLONIZATION 119 volatile issue the confusion is compounded. Northern Ireland is a good contemporary example. Colonization has been studied by numerous individuals, but a definitive volume on the entire movement still has not been compiled. The motivation factor must be placed at the center of such a work. -

COASTAL ENGINEERING in SOUTH AFRICA by K S RUSSELL 1. INTRODUCTION the Paper Presents a Review of the Historical Movement Of

COASTAL ENGINEERING IN SOUTH AFRICA by K S RUSSELL 1. INTRODUCTION The paper presents a review of the historical movement of ships around the South African coastline, traces the evolution and development of the harbours of South Africa, describes the development of coastal engineering and summarises the organisations and their activities in both basic and applied research projects contributing towards coastal works. 2. HISTORICAL The coastal currents and winds have played a major role in the historic exploration of the African coast. The earliest reference to a circum- navigation of Africa, although unconfirmed, was that by Herodotus who, in about 600 B.C. wrote that the Pharaoh Necho (Neco), then at war with the Syrians and wishing to combine his Mediterranean and Red Sea fleets, caused a fleet of ships manned by Phoenicians to sail from the Erythraean (Red) Sea and return through the Pillars of Hercules (Straits of Gibraltar). The journey is reputed to have taken three years; wind and currents make such a voyage in square-rigged boats a possibility. Fig,1. Ocean currents in the Southern hemisphere. The Restless Seas. Fig.2. The earliest navigations around Africa. Southern Land. A.R.Wilcox. National Research Institute for Oceanology, Stellenbosch, South Africa 2322 SOUTH AFRICA 2323 Accounts exist of voyages on the west coast by Hanno (c.500BC) who, with a fleet of 60 ships, explored as far as Cape Palmas (Liberia), and of Sataspes (c.475BC) who, in an attempt to sail around Libya (Africa) on the west and return by the Arabian Gulf (Red Sea), reached a similar destination. -

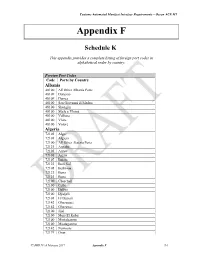

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

Permanent Missions to the United Nations

ST/SG/SER.A/301 Executive Office of the Secretary-General Protocol and Liaison Service Permanent Missions to the United Nations Nº 301 March 2011 United Nations, New York Note: This publication is prepared by the Protocol and Liaison Service for information purposes only. The listings relating to the permanent missions are based on information communicated to the Protocol and Liaison Service by the permanent missions, and their publication is intended for the use of delegations and the Secretariat. They do not include all diplomatic and administrative staff exercising official functions in connection with the United Nations. Further information concerning names of members of permanent missions entitled to diplomatic privileges and immunities and other mission members registered with the United Nations can be obtained from: Protocol and Liaison Service Room NL-2058 United Nations New York, N.Y., 10017 Telephone: (212) 963-7174 Telefax: (212) 963-1921 website: http://www.un.int/protocol All changes and additions to this publication should be communicated to the above Service. Language: English Sales No.: E.11.I.8 ISBN-13: 978-92-1-101241-5 e-ISBN-13: 978-92-1-054420-7 Contents I. Member States maintaining permanent missions at Headquarters Afghanistan.......... 2 Czech Republic..... 71 Kenya ............. 147 Albania .............. 4 Democratic People’s Kuwait ............ 149 Algeria .............. 5 Republic Kyrgyzstan ........ 151 Andorra ............. 7 of Korea ......... 73 Lao People’s Angola .............. 8 Democratic Republic Democratic Antigua of the Congo ..... 74 Republic ........ 152 and Barbuda ..... 10 Denmark ........... 75 Latvia ............. 153 Argentina ........... 11 Djibouti ............ 77 Lebanon........... 154 Armenia ............ 13 Dominica ........... 78 Lesotho ........... 155 Australia............ 14 Dominican Liberia ........... -

The Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes, Rare Types

American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 175C:70–115 (2017) RESEARCH REVIEW The Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes, Rare Types ANGELA F. BRADY, SERWET DEMIRDAS, SYLVIE FOURNEL-GIGLEUX, NEETI GHALI, CECILIA GIUNTA, INES KAPFERER-SEEBACHER, TOMOKI KOSHO, ROBERTO MENDOZA-LONDONO, MICHAEL F. POPE, MARIANNE ROHRBACH, TIM VAN DAMME, ANTHONY VANDERSTEEN, CAROLINE VAN MOURIK, NICOL VOERMANS, JOHANNES ZSCHOCKE, AND FRANSISKA MALFAIT * Dr. Angela F. Brady, F.R.C.P., Ph.D., is a Consultant Clinical Geneticist at the North West Thames Regional Genetics Service, London and she has a specialist interest in Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome. She was involved in setting up the UK National EDS Diagnostic Service which was established in 2009 and she has been working in the London part of the service since 2015. Dr. Serwet Demirdas, M.D., Ph.D., is a clinical geneticist in training at the Erasmus Medical Center (Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands), where she is involved in the clinical service and research into the TNX deficient type of EDS. Prof. Sylvie Fournel-Gigleux, Pharm.D., Ph.D., is a basic researcher in biochemistry/pharmacology, Research Director at INSERM (Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Medicale) and co-head of the MolCelTEG Research Team at UMR 7561 CNRS-Universite de Lorraine. Her group is dedicated to the pathobiology of connective tissue disorders, in particular the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes, and specializes on the molecular and structural basis of glycosaminoglycan synthesis enzyme defects. Dr. Neeti Ghali, M.R.C.P.C.H., M.D., is a Consultant Clinical Geneticist at the North West Thames Regional Genetics Service, London and she has a specialist interest in Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome. -

Passeport Pour La CAN 2012 Xxviiie COUPE D'afrique DES NATIONS DE FOOTBALL Gabon & Guinée Équatoriale 21 Janvier

Passeport pour la CAN 2012 XXVIIIe COUPE D’AFRIQUE DES NATIONS DE FOOTBALL Gabon & Guinée Équatoriale 21 janvier – 12 février 2012 Ré alisé par Rfi Multimedia 1 INTRODUCTION La CAN se déroule pour la deuxième fois seulement de son histoire en Afrique centrale. Quarante ans après l’édition 1972 au Cameroun, le Gabon et la Guinée équatoriale coorganisent la plus grande manifestation sportive du continent. Contrairement à la CAN 2000 au Nigeria et au Ghana, c’est un mariage de raison qui rassemble Gabonais et Equato-Guinéens. Les deux Fédérations de football ont uni leurs forces pour cette occasion. Le pari est difficile mais il est beau car cette CAN 2012 s’annonce palpitante. Pour la première fois depuis la CAN 1996 et le forfait de la sélection nigériane, le vainqueur est absent lors de la phase finale suivante. Les Pharaons d’Egypte, malgré leurs sept sacres, n’ont pas franchi les éliminatoires, comme les Camerounais (4 trophées), les Nigérians (2 trophées), les Léopards de RD Congo (2) et les Algériens (1). Les équipes du Ghana et de la Côte d’Ivoire, présentes lors de la Coupe du monde 2010, seront donc les favorites du tournoi. Il faudra aussi compter avec le Sénégal et le Maroc qui reviennent fort après avoir manqué la Coupe d’Afrique 2010. Cette toute dernière CAN disputée une année paire permettra aussi au grand public, de découvrir de nouveaux joueurs. Les Botswanais, les Equato-Guinéens et les Nigériens feront leurs tous premiers pas dans la compétition. Souhaitons-leur que cette 28e édition ressemble plus à la très belle CAN 2008 qu’à la décevante CAN 2010.