COASTAL ENGINEERING in SOUTH AFRICA by K S RUSSELL 1. INTRODUCTION the Paper Presents a Review of the Historical Movement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phytoplankton Composition at Jeddah Coast–Red Sea, Saudi Arabia in Relation to Some Ecological Factors

JKAU: Sci., Vol. 22 No. 1, pp: 115-131 (2010 A.D. / 1431 A.H.); DOI: 10.4197 / Sci. 22-1.9 Phytoplankton Composition at Jeddah Coast–Red Sea, Saudi Arabia in Relation to some Ecological Factors Hussein E. Touliabah1, Wafaa S. Abu El-Kheir1 , Mohammed Gurban Kuchari2 and Najah Ibrahim Hassan Abdulwassi3 1 Botany Dept., Faculty of Girls, Ain Shams University, Cairo, 2 Egypt, Faculty Science, King Abdulaziz University, and 3 Faculty of Girls, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Abstract. Phytoplankton succession in relation to some physico- chemical characters of some water bodies at Jeddah Coast (Saudi Arabia) was studied for one year (2004). The sampling program included four different areas, North Obhour, Technology area, Down Town area and South Jeddah Area. Water samples were analyzed for some physico-chemical parameters (Temperature, pH, S‰, Dissolved +2 +2 Oxygen (DO), Calcium (Ca ) & Magnesium (Mg ), Nitrite (NO2), Nitrate (NO3), Ammonia (NH3), Reactive Orthophosphate (PO4) and Reactive Silicate (SiO3) as well as phycological parameters (Phytoplankton communities and Chlorophyll a). The Jeddah Coast was found to be oligotrophic ecosystem in some areas, while some of these areas were mesotrophic with high phytoplankton density such as the Down Town and South Jeddah areas. The results showed that, the high phytoplankton density attaining the maximum of 2623.2 X 103/m3 at Down Town area during spring and the minimum of 118.7 X 103/m3 at Technology area during winter. Seventy three species belonging to 73 genera and 5 groups were recorded. Dinophyceae was the first dominant group forming 43.8% of the total phytoplankton communities followed by Bacillariophyceae 27.9%. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

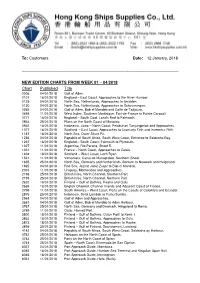

12 January, 2018 NEW EDITION CHARTS from WEEK 01

To: Customers Date: 12 January, 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ NEW EDITION CHARTS FROM WEEK 01 – 04/2018 Chart Published Title 0006 04/01/2018 Gulf of Aden. 0107 18/01/2018 England – East Coast, Approaches to the River Humber. 0125 04/01/2018 North Sea, Netherlands, Approaches to Ijmuiden. 0130 04/01/2018 North Sea, Netherlands, Approaches to Scheveningen. 0265 04/01/2018 Gulf of Aden, Bab el Mandeb and Golfe de Tadjoura. 0494 11/01/2018 West Indies, Southern Martinique, Fort-de-France to Pointe Caracoli. 0777 18/01/2018 England – South Coat, Land’s End to Falmouth. 0863 25/01/2018 Plans on the North Coast of Morocco. 0932 18/01/2018 Indonesia, Jawa – North Coast, Pelabuhan Tanjungpriok and Approaches. 1077 18/01/2018 Scotland – East Coast, Approaches to Cromarty Firth and Inverness Firth. 1187 18/01/2018 North Sea, Outer Silver Pit. 1236 04/01/2018 Republic of South Africa, South West Coast, Entrance to Saldanha Bay. 1267 18/01/2018 England – South Coast, Falmouth to Plymouth. 1327 11/01/2018 Argentina, Rio Parana, Sheet 5. 1351 11/01/2018 France – North Coast, Approaches to Calais. 1404 18/01/2018 Scotland – West Coast, Loch Ryan. 1521 11/01/2018 Venezuela, Canal de Maraqcaibo, Southern Sheet. 1635 25/01/2018 North Sea, Germany and Netherlands, Borkum to Neuwerk and Helgoland. 1925 04/01/2018 Red Sea, Jazirat Jabal Zuqar to Bab el Mandeb. 2001 11/01/2018 Uruguay, Montevideo and Approaches. 2198 25/01/2018 British Isles, North Channel, Southern Part. 2199 25/01/2018 British Isles, North Channel, Northern Part. -

Population Trends of Seabirds Breeding in South Africa's Eastern Cape and the Possible Influence of Anthropogenic and Environ

Crawford et al.: Population trends of seabirds breeding in South Africa 159 POPULATION TRENDS OF SEABIRDS BREEDING IN SOUTH AFRICA’S EASTERN CAPE AND THE POSSIBLE INFLUENCE OF ANTHROPOGENIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE ROBERT J.M. CRAWFORD,1,2 PHILIP A. WHITTINGTON,3,4 A. PAUL MARTIN,5 ANTHONY J. TREE4,6 & AZWIANEWI B. MAKHADO1 1Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Marine and Coastal Management, Private Bag X2, Rogge Bay, 8012, South Africa ([email protected]) 2Animal Demography Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa 3East London Museum, PO Box 11021, Southernwood, 5213, South Africa 4Department of Zoology, PO Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, 6031, South Africa 5PO Box 61029, Bluewater Bay, 6212, South Africa 6PO Box 211, Bathurst, 6166, South Africa Received 28 August 2008, accepted 4 April 2009 SUMMARY CRAWFORD, R.J.M., WHITTINGTON, P.A., MARTIN, A.P., TREE, A.J. & MAKHADO, A.B. 2009. Population trends of seabirds breeding in South Africa’s Eastern Cape and the possible influence of anthropogenic and environmental change. Marine Ornithology 37: 159–174. Eleven species of seabird breed in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province. Numbers of African Penguin Spheniscus demersus and Cape Gannet Morus capensis in the province increased in the 20th century, but penguins decreased in the early 21st century. A recent eastward displacement of Sardine Sardinops sagax off South Africa increased the availability of this food source to gannets but did not benefit penguins, which have a shorter foraging range. Fishing and harbour developments may have influenced the recent decrease of penguins. -

SA Wioresearchcompendium.Pdf

Compiling authors Dr Angus Paterson Prof. Juliet Hermes Dr Tommy Bornman Tracy Klarenbeek Dr Gilbert Siko Rose Palmer Report design: Rose Palmer Contributing authors Prof. Janine Adams Ms Maryke Musson Prof. Isabelle Ansorge Mr Mduduzi Mzimela Dr Björn Backeberg Mr Ashley Naidoo Prof. Paulette Bloomer Dr Larry Oellermann Dr Thomas Bornman Ryan Palmer Dr Hayley Cawthra Dr Angus Paterson Geremy Cliff Dr Brilliant Petja Prof. Rosemary Dorrington Nicole du Plessis Dr Thembinkosi Steven Dlaza Dr Anthony Ribbink Prof. Ken Findlay Prof. Chris Reason Prof. William Froneman Prof. Michael Roberts Dr Enrico Gennari Prof. Mathieu Rouault Dr Issufo Halo Prof. Ursula Scharler Dr. Jean Harris Dr Gilbert Siko Prof. Juliet Hermes Dr Kerry Sink Dr Jenny Huggett Dr Gavin Snow Tracy Klarenbeek Johan Stander Prof. Mandy Lombard Dr Neville Sweijd Neil Malan Prof. Peter Teske Benita Maritz Dr Niall Vine Meaghen McCord Prof. Sophie von der Heydem Tammy Morris SA RESEARCH IN THE WIO ContEnts INDEX of rEsEarCh topiCs ‑ 2 introDuCtion ‑ 3 thE WEstErn inDian oCEan ‑ 4 rEsEarCh ActivitiEs ‑ 6 govErnmEnt DEpartmEnts ‑ 7 Department of Science & Technology (DST) Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries (DAFF) sCiEnCE CounCils & rEsEarCh institutions ‑ 13 National Research Foundation (NRF) Council for Geoscience (CGS) Council for Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) Institute for Maritime Technology (IMT) KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board (KZNSB) South African Environmental Observation Network (SAEON) Egagasini node South African -

99 UPWELLING in the GULF of GUINEA Results of a Mathematical

99 UPWELLING IN THE GULF OF GUINEA Results of a mathematical model 2 2 6 5 0 A. BAH Mécanique des Fluides géophysiques, Université de Liège, Liège (Belgium) ABSTRACT A numerical simulation of the oceanic response of an x-y-t two-layer model on the 3-plane to an increase of the wind stress is discussed in the case of the tro pical Atlantic Ocean. It is shown first that the method of mass transport is more suitable for the present study than the method of mean velocity, especially in the case of non-linearity. The results indicate that upwelling in the oceanic equatorial region is due to the eastward propagating equatorially trapped Kelvin wave, and that in the coastal region upwelling is due to the westward propagating reflected Rossby waves and to the poleward propagating Kelvin wave. The amplification due to non- linearity can be about 25 % in a month. The role of the non-rectilinear coast is clearly shown by the coastal upwelling which is more intense east than west of the three main capes of the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, by day 90 after the wind's onset, the maximum of upwelling is located east of Cape Three Points, in good agree ment with observations. INTRODUCTION When they cross over the Gulf of Guinea, monsoonal winds take up humidity and subsequently discharge it over the African Continent in the form of precipitation (Fig. 1). The upwelling observed during the northern hemisphere summer along the coast of the Gulf of Guinea can reduce oceanic evaporation, and thereby affect the rainfall pattern in the SAHEL region. -

Chapter 3: Description of the Affected Environment

Proposed extension to the container berth and construction of an administration craft basin at the Port of Ngqura Chapter 3 : Description of the Affected Environment Chapter 3: Description of the Affected Environment Final Scoping Report – CSIR, April 2007 Page i Proposed extension to the container berth and construction of an administration craft basin at the Port of Ngqura Chapter 3 : Description of the Affected Environment Description of the Affected Environment 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT________ 3-1 3.1 Introduction _________________________________________________________3-1 3.2 Site location_________________________________________________________3-1 3.3 Biophysical environment _______________________________________________3-2 3.3.1 Climate ____________________________________________________________ 3-2 3.3.2 Terrestrial features: landscape and geology ________________________________ 3-2 3.3.3 Vegetation __________________________________________________________ 3-3 3.3.4 Birds ______________________________________________________________ 3-3 3.3.5 Marine ecosystems ___________________________________________________ 3-3 3.4 Socio-economic environment ___________________________________________3-4 3.4.1 Demographics and human development___________________________________ 3-4 3.4.2 In-migration _________________________________________________________ 3-4 3.4.3 Initiatives to promote economic development _______________________________ 3-5 Final Scoping Report – CSIR, April 2007 Page ii Proposed extension to the -

J.E.Afr.Nat.Hist.Soc. Vol.XXV No.3 (112) January 1966 CHECK LIST of ELOPOID and CLUPEOID FISHES in EAST AFRICAN COASTAL WATERS B

J.E.Afr.Nat.Hist.Soc. Vol.XXV No.3 (112) January 1966 CHECK LIST OF ELOPOID AND CLUPEOID FISHES IN EAST AFRICAN COASTAL WATERS By G.F. LOOSE (East African Marine Fisheries Research Organization, Zanzibar.) Introduction During preliminary biological studies of the economically important fishes of the suborders Elopoidei and Clupeoidei in East African coastal waters, it was found that due to considerable confusion in the existing literature and the taxonomy of many genera, accurate identifi• cations were often difficult. A large collection of elopoid and clupeoid fishes has been made. Specimens have been obtained from purse-seine catches, by trawling in estuaries and shallow bays, by seining, handnetting under lamps at night, and from the catches of indigenous fishermen. A representative fartNaturalof thisHistory),collectionLondon,haswherenow beenI wasdepositedable to examinein the Britishfurther Museummaterial from the Western Indian Ocean during the summer of 1964. Based on these collections this check list has been prepared; a review on the taxonomy, fishery and existing biological knowledge of elopoid and clupeoid species in the East African area is in preparation. Twenty-one species, representing seven families are listed here; four not previously published distributional records are indicated by asterisks. Classification to familial level is based on Whitehead, P.J.P. (1963 a). Keys refer only to species listed and adult fishes. In the synonymy reference is made only to the original description and other subsequent records from the area. Only those localities are listed from which I have examined specimens. East Africa refers to the coastal waters of Kenya and Tanzania and the offshore islands of Pemba, Zanzibar and Mafia; Eastern Africa refers to the eastern side of the African continent, i.e. -

Joint Geological Survey/University of Cape Town MARINE GEOSCIENCE UNIT TECHNICAL ^REPORT NO. 13 PROGRESS REPORTS for the YEARS 1

Joint Geological Survey/University of Cape Town MARINE GEOSCIENCE UNIT TECHNICAL ^REPORT NO. 13 PROGRESS REPORTS FOR THE YEARS 1981-1982 Marine Geoscience Group Department of Geology University of Cape Town December 1982 NGU-Tfc—Kh JOINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY/UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN MARINE GEOSCIENCE UNIT TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 13 PROGRESS REPORTS FOR THE YEARS 1981-1982 Marine Geoscience Group Department of Geology University of Cape Town December 1982 The Joint Geological Survey/University of Cape Town Marine Geoscience Unit is jointly funded by the two parent organizations to promote marine geoscientific activity in South Africa. The Geological Survey Director, Mr L.N.J. Engelbrecht, and the University Research Committee are thanked for their continued generous financial and technical support for this work. The Unit was established in 1975 by the amalgamation of the Marine Geology Programme (funded by SANCOR until 1972) and the Marine Geophysical Unit. Financial ?nd technical assistance from the South African National Committee for Oceanographic Research, and the National Research Institute for Oceanology (Stellenbosch) are also gratefully acknowledged. It is the policy of the Geological Survey and the University of Cape Town that the data obtained may be presented in the form of theses for higher degrees and that completed projects shall be published without delay in appropriate media. The data and conclusions contained in this report are made available for the information of the international scientific community with tl~e request that they be not published in any manner without written permission. CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION by R.V.Dingle i PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE BATHYMETRY OF PART OF 1 THE TRANSKEI BASIN by S.H. -

Economic State and Growth Prospects of the 12 Proclaimed Fishing Harbours in the Western Cape

Department of the Premier Report on the Economic and Socio- Economic State and Growth Prospects of the 12 Proclaimed Fishing Harbours in the Western Cape November 2012 Final consolidated report TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ i 1 Introduction and purpose ................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project approach ..................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project background ................................................................................................. 3 2 Policy and institutional context ........................................................................ 4 2.1 Historical context ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Local government context ....................................................................................... 4 2.3 Policy governing fishing harbours ........................................................................... 6 2.4 Key legislation relevant to fishing harbour governance............................................ 8 2.5 Previous investigations into harbour governance and management models to promote local socio-economic gains ..................................................................... 10 3 Assessment of fishing harbours and communities ...................................... 15 3.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

Final Msc Thesis

THE ZOOGEOGRAPHY OF THE CETACEANS IN ALGOA BAY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE of RHODES UNIVERSITY by BRIGITTE LEIGH MELLY January 2011 ABSTRACT The most recent study on cetaceans in Algoa Bay, South Africa, was conducted over 14 years ago. Consequently, knowledge of the cetacean species visiting this bay is currently based on incidental observations and stranding data. A number of developments in recent years: a deep- water port, proposed oil refinery, increased boating and fishing (commercial and recreational), a proposed Marine Protected Area, and the release of a whale-watching permit, all of which may impact these animals in some way, highlight the need for a baseline study on cetaceans. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the spatial and temporal distribution, and habitat preference of cetaceans in Algoa Bay. Boat-based surveys were conducted monthly between March 2009 and July 2010. At each sighting the GPS location, species, group size and composition, and behaviour were recorded. Using GIS, the sighting data was related to data layers of geographical variables such as sea surface temperature, depth and sea-floor substrate. Approximately 365 hours of search effort were completed over 57 surveys, with a total of 346 sightings. Species observed were: southern right whales (Eubalaena australis), humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera brydei), Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus), Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (Sousa chinensis), and long- beaked common dolphins (Delphinus capensis). Southern right whales were observed during austral winter, utilising the shallow, protected areas of the bay as a mating and nursery ground. -

To Marine Meteorological Services

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION Guide to Marine Meteorological Services Third edition PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS PUBLICATION IS GOING TO BE UPDATED BY END OF 2010. WMO-No. 471 Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization - Geneva - Switzerland 2001 © 2001, World Meteorological Organization ISBN 92-63-13471-5 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE FOR NOTING SUPPLEMENTS RECEIVED Supplement Dated Inserted in the publication No. by date 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 CONTENTS Page FOREWORD................................................................................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... xi CHAPTER 1 — MARINE METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES ........................................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Requirements for marine meteorological information....................................................................... 1-1 1.2.1