Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROTC Page7 President Reagan Ends Six-Day Trip to Communist

ROTC page7 VOL XVIII, NO. 135 the independent ~tudent new~paper ~lT\ing notn dame and .,amtmary·, TUESDAY, MAY 1,1984 President Reagan ends six-day trip to Communist China on good note Associated Press gether to write a new chapter of "We have seen your great monu· peace and progress for our people." ments such as the Great Wall. But SHANGHAI, China - President "My visit to China leaves me we're not working in mortar and Reagan received the warmest confident that U.S.-China relations stone here. My hope is that we can welcorpe of his six-day visit to China arc good and getting better," he said. accomplish something between and said at a farewell banquet that ourselves that will also be remem the United States and China are plan· The president returns to the bered 1,000 years from now." ning "to write a new chapter of United States today, crossing the in peace and progress." ternational dateline and landing in From the farewell ceremony in Winding up his final day in China Fairbanks, Alaska. after first visiting a Peking, Reagan flew south to this at a banquet given by Shanghai child care center and modest private teeming city of 12 million. Mayor Wang Daohan, Reagan said, residence at a commune on May Addressing more than 1 ,000 stu "My trip to China has been as impor· Day, the international workers· dents in a handpicked audience at tant and enlightening as any I've holiday. Fudan University, where a huge taken as pn:sident." As China prepared to celebrate statue of the late Mao Tse·tung Reagan also finally got an oppor· the two-day holiday. -

Scenes and Impressions Abroad

SCENES IMPRESSIONS ABROAD. E Y THE REV. J. E. ROCKWELL, D.D. NEW YORK: ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS No. 580 BROADWAY. 1860. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by ROBERT CARTER AND BROTHERS, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York, EDWARD O. JENKINS, Printer # &tcrfotgper, No. 26 Frankfort Strket. ^s Sng*T>y -^-K. Biis/iia - fast^J ^.^T^tc^U^ TO MY WIFE, WHOSE SOCIETY WAS THE CHAEM WHICH MADE THESE SCENES- DELIGHTFUL AND MEMORABLE; TO MY PARENTS, WHOSE IN8TKUCTIONS AND COUNSELS HAVE EVER BEEN WISE, FAITHFUL AND SAFE; TO THE CENTRAL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF BROOKLYN, WHOSE SYMPATHY AND EARNEST CO-OPERATION HAVE MADE MY WORK AS A PASTOR PLEASANT; THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED WITH EVERY FEELING OF RESPECT AND AFFECTION BY THE AUTHOR. SCENES AND IMPRESSIONS ABROAD, PREFACE, The substance of these Scenes and Impres- sions Abroad was presented in the form of a Series of Lectures, before the congregation to which it is my pleasure to minister, without a thought of giving to them any farther pub- licity. Unexpectedly they enlisted such atten- tion and apparent interest, as that it became necessary to adjourn from my Lecture Koom, where they were commenced, to the main Auditory of the Church, which place was filled every Wednesday evening for three months. Most of the Lectures were very fully reported in the columns of the Transcript, of this city, with kind and courteous notices of the course. At the request of many who heard them, or who had read the reports of them, and in Vlll PREFACE. -

Frustration, Honor and Death in the Trilogy of Federico Garcia Lorca

(RJELAL) Research Journal of English Language and Literature Vol.4.Issue 3. 2016 A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal (July-Sept.) http://www.rjelal.com; Email:[email protected] RESEARCH ARTICLE FRUSTRATION, HONOR AND DEATH IN THE TRILOGY OF FEDERICO GARCIA LORCA BINDIYA RAHI SINGH JRF Research Scholar Guest Assistant Professor ABSTRACT In this research Paper, we will try to light on the theme of frustration honour and death in the plays of Federico Garcia Lorca who is the most eminent painter, singer of Andalusia Folklore and a poet of gipsy ballads. He was the master of Puppet theatre. His surrealistic style makes him the greatest dramatist among other contemporaries dramatist. It was his great writing for the Spanish Literature that he wrote rural trilogy as Blood wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba. Following these plays he knits the symbolical background with the Aristotelian BINDIYA RAHI concepts. His first play Blood Wedding is based on the theme of bloodshed and feud SINGH between two families which ends with thirst of murder to Bridegroom and Leonardo who belongs to the Felix Family and second one, Yerma is cry of a barren mother who murdered her husband in order to not satisfy her desire to be a mother and after abuse by her husband and last one The House Of Bernarda Alba ends with the death of honor of Adela by the orthodox cal attitude of Bernarda Alba. So this trilogy highlights the eminent features of his dramatic style overwhelming stresses and tensions throughout his entire plays along with, they have many symbolical songs in it. -

"Federico García Lorca's Blood Wedding (1932): Patriarchy's Tragic

Bonaddio, Federico. "Federico García Lorca’s Blood Wedding (1932): Patriarchy’s Tragic Flaws." Patriarchal Moments: Reading Patriarchal Texts. Ed. Cesare Cuttica. Ed. Gaby Mahlberg. : Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 163–170. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472589163.ch-021>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 05:58 UTC. Copyright © Cesare Cuttica, Gaby Mahlberg and the Contributors 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 20 Federico García Lorca’s Blood Wedding (1932): Patriarchy’s Tragic Flaws1 Federico Bonaddio [It’s wedding day somewhere in rural Andalusia, and the mother of the groom and father of the bride are sharing a private conversation.] MOTHER: That’s what I’m hoping for: grandchildren. (They sit.) FATHER: I want them to have plenty. This land needs hands that aren’t hired. You’re forever battling weeds, thistles, stones that appear from nowhere. And those hands should be the owners’ own, able to punish and master, to make the seed grow. You need a lot of sons. MOTHER: And a daughter or two! Men come and go like the wind! It’s in their nature to turn to knives and guns. Girls never venture out of the house. FATHER (Happily): I’m sure they’ll have both. MOTHER: My son will cover her well. He’s of good stock. His father could have had plenty of children with me. FATHER: I wish it could all happen in a day. -

Blood Wedding

Written by Federico Garcia Lorca, Directed by Dr. Keith Byron Kirk Study Guide The University of Houston School of Theatre and Dance is pleased to present this study guide arranged by the BFA Theatre Education majors. We hope that you i find the activities, photos, and script analysis enriching to your classroom expe- j rience and helpful as a companion to Blood Wedding. qblh Table of Contents Who Setting the Stage........................2 Who’s Who.................................3 Meet Lorca..................................4 What Opportunity Cost Game...........5 Blood Wedding Budgeting..........7 When A Light in Dark..........................9 A Wedding’s History................11 Where Cryptic or Beautiful?..............13 Committee Work Activity.......15 Why Themes of Blood Wedding........17 Altering a Lullaby ....................19 The Design of Life...................21 Mask Making Methods..............23 How Spaghetti Math...........................24 Gobo Creations.........................26 Use your QR scanning device or smartphone to learn more about The School of Theatre and Dance! 1 Setting The Stage The play begins with a scene between Federico Garcia Lorca and Margarita Xirgu. As they speak, the members of the La Barraca theatre troupe explain not only Lorca’s history but the critical views of his writing. Lorca begins writing the play “Blood Wedding.” The Mother and the Bridegroom, have a conversation about the Mother’s hatred of knives - the Bridegroom’s father and brother were murdered by members of the Felix family. They talk about the Bride- groom’s hope to be married to the Bride. After he exits, a Neighbor visits the Mother, revealing that the Bride was once the lover of Leonardo Felix. -

Teacher's Guide by Jerry Hawkins, Co-Founder of the Imagining Freedom Institute CARA MÍA THEATRE's Ursula, Or Let Yourself Go with the Wind

URSULA OR LET YOURSELF GO WITH THE WIND A PLAY WRITTEN AND PERFORMED BY FRIDA ESPINOSA-MüLLER Teacher's Guide by Jerry Hawkins, co-founder of The Imagining Freedom Institute CARA MÍA THEATRE'S Ursula, or Let Yourself Go with the Wind IN THIS TEACHER'S GUIDE YOU WILL FIND Pre-Show Guide Synopsis Investigation 1 Compares migration and immigration journeys and connects how they are similar. Activity: What is your family’s story? Mid-Show Guide Investigation 2 Borders are political boundaries, not human boundaries. Activity: What is a border? Post-Show Guide Investigation 3 Provides an opportunity for students to take inventory of their thoughts and emotions after watching the play while reflecting on our shared commonalities as diverse individuals. Activity: What are our connections? Biographies Cara Mía Theatre The Imagining Freedom Institute Frida Espinosa Müller (Playwright and Performer) Jerry Hawkins (Study Guide Author) Please be aware that all property and materials that you access before, during, or after watching the educational play Ursula or Let Yourself Go with the Wind, belong to Cara Mía Theatre Company with special permission given to Dallas ISD for distribution to its staff members and their students only. IF YOU ENCOUNTER ANY TECHNICAL ISSUES OR HAVE ANY QUESTIONS Email Cara Mía Theatre's Education and Community Action Coordinator Cheyenne Raquel Farley at [email protected] or call (214) 516 - 0706. EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS AT CARA MÍA THEATRE PRE-SHOW TEACHER'S GUIDE Grades 7- 12 URSULA OR LET YOURSELF GO WITH THE WIND PRE-SHOW TEACHER'S GUIDE / Grades 7 - 12 ABOUT THE PLAY With a minimal set, various puppets, and a performance rooted in movement, performer Frida Espinosa Müller transforms into over 10 characters to tell this story of child detention at the Southern border through the mind of a child. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

Eileen Stevens

"'LetEach Becone Aware" Founded 1957, Incorporated 1976 Volume XXXIX, Number 21 Monday, November 13, 1995 : First Copy lFree- University Senate Passes (quality of Teaching Propos1a, _w BY ENEILRYAN DE LA PENA departmental and university-wide for commuting students. order to gain student support. "I think [students] should at Statesman Editor training program. "There was a lot of least be able to understand their The University Senate . "In general, [the proposal] discussion," Mackin said, teachers, but-I think they should passed a. proposal at last 3. All teachers,- in will help the.students,-" said referring to the University Senate be strict on [enacting the Monday's'meeting that will undergraduate' course-both' Nicole Rosner, :Polity vice voting on the proposals, -last proposals]," said Natalie Jacobs, ultimately improve the quality of faculty and TA's-must speak, president and member of the Monday. "There were still a lot a sophomore. "A teacher can still teaching at Stony Brook, English at a level appropriate to Undergraduate Council, of people disagreeing with it.- be pretty, good at handling the according to James Mackin, classroom instruction or other referring to the TA's who do not The vote came up 37 to 5 in favor accent, but they must get their professor and' chair of the teaching duties. fluently speak English. "I don't of adopting them." Since the point across." Undergraduate Council. think it's fair that students go into proposals have been passed in the Sophia Campbell, a junior, Mackin, along 'with 4.' When possible, faculty classes while they can't Senate, they are now currently in -strongly agreed with the members of the Ad Hoc should be given credit for understand the TA." effect, said Mackin. -

The Winter's Tale Study Guide Table of Contents Summary

The Winter's Tale Study Guide Table of Contents Summary..............................................................................................................................................................1 Biography.............................................................................................................................................................4 Themes.................................................................................................................................................................6 Characters...........................................................................................................................................................9 Critical Essays...................................................................................................................................................13 Analysis............................................................................................................................................................891 Quotes...............................................................................................................................................................896 i Summary Summary Polixenes, the king of Bohemia, is the guest of Leontes, the king of Sicilia. The two men were friends since boyhood, and there is much celebrating and joyousness during the visit. At last Polixenes decides that he must return to his home country. Leontes urges him to extend his visit, but Polixenes refuses, saying that -

STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA Grace Presbyterian Church Library; 7:00Pm; Tuesday, November 17, 2015

STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA Grace Presbyterian Church Library; 7:00pm; Tuesday, November 17, 2015 CALL TO ORDER AND OPENING PRAYER – The Rev. Trey Little CLERK’S REPORT & ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS – David Finck, Clerk of Session • Consent Agenda MODERATOR’S REPORT – The Rev. Trey Little • Examination of Class of 2018 Church Officers • Election of Ruling Elder Commissioners for ECO National Meeting (January 26 – 28, 2016) • Facilities Improvement Team Update • ECO Discipleship Pilot Phase Update • Resolution to Dissolve Pastor Nominating Committee • Calling of a Congregational Meeting on Sunday, January 10, for the Purposes of: o Electing Class of 2018 Deacons and Trustees o Electing Church Officer Nominating Committee o Electing Grace Endowment Fund Trustees COMMITTEE REPORTS: ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE GRACE SCHOOL • See written report attached • No written report provided • Pastors’ Compensation MARRIED LIFE ADULT & JOY • No written report provided • See written report attached MISSIONS CONGREGATIONAL CARE • See written report attached • See written report attached WORSHIP EVANGELISM • See written report attached • See written report attached YOUNG ADULT & COLLEGE FAMILY • See written report attached • See written report attached CLOSING PRAYER NEXT SESSION MEETING: Tuesday, January 19 STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA – November 17, 2015 Grace Presbyterian Church Session Business Meeting CONSENT AGENDA Tuesday, November 17, 2015 § Approve Minutes of the October 20, 2015 stated Session meeting. § Approve Minutes of the November 1, 2015 called -

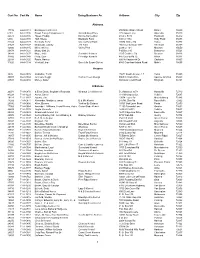

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

(Goff) Genealogy

Family History 1470 -1933 BLOOD.... CABOT HICKS... GOULD AND ALLIED BRANCHES GRACE CABOT BLOOD TOLER THT•J lNDEPENDEXT PRr~:fiS TOLEl:t & TOLii~H. PtrHLrSHERS Genealogical Record OF 'l'HE DESCENDANTS OF RICHARD BLOOD-BAPTIST HICKS AND ALLIED FAMILlZS -1470-1933- INCI.. UDES THE FAMILIES OF Alynt Batt, Benjamin, Billington, Bow:-en_, Cabot,. ea.~e.y.., Chase; Clark, .•!. •.Cl~a~es,.. _.Q>9&Ai,..; :."'--~P'W,.. Darling.. DaV;ts; Dwi.ght,. Eggleston, Eyart, -flint,, Follansbee, Gifford, Gotfe, Gouldt Gru.chy, Han more, HaTWood, Hodgeman-,. i 'l{olden, Hor.ton. J.ahns9n, K!insley, · Liv.ermal:'e, .JA)ngley, Le :a.,:or-ru,, Mansfield. Marrel-1, Marston,. .Martin, Moulton,. Mowry; Nutting, Page; -Pa:rtridge, Pow.ers" ·Rodaera, Bosst· Sabin, Salisbury, Shepard, Tha~~ er, -Toler, Walton, Webster, Whitcomb and Wright. OOM'PILSD AND EDITED BY GRACE CABOT TOLER FOREWORD HE FAAIILY history contained within the pages of this book has been• ··tiff the making -i:11 · my·= mitid since, ~s a small ch.il~. I follo\ved;;~y fa_~_llet· a:ound liste~- T 1ng to everything he had to say pertaining to his. early experiences and to his ancestry, My mother had less to say about her anc.estry and early lite but here and there I gleaned a little from chance remarks. My pa· enta \\·ere in their middle age when I was bo1·n and by the tin1e I bal reach... e~ my teens, my f'ather, especially, was d'\\·eliing ofttm in tht! past. As I gre\\· older; I beg.&n Jotting down the items of fan1- ily interest ·artd after I ma:,rr.i.~tl~!f,~~)" .