Sunday, January 28, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROTC Page7 President Reagan Ends Six-Day Trip to Communist

ROTC page7 VOL XVIII, NO. 135 the independent ~tudent new~paper ~lT\ing notn dame and .,amtmary·, TUESDAY, MAY 1,1984 President Reagan ends six-day trip to Communist China on good note Associated Press gether to write a new chapter of "We have seen your great monu· peace and progress for our people." ments such as the Great Wall. But SHANGHAI, China - President "My visit to China leaves me we're not working in mortar and Reagan received the warmest confident that U.S.-China relations stone here. My hope is that we can welcorpe of his six-day visit to China arc good and getting better," he said. accomplish something between and said at a farewell banquet that ourselves that will also be remem the United States and China are plan· The president returns to the bered 1,000 years from now." ning "to write a new chapter of United States today, crossing the in peace and progress." ternational dateline and landing in From the farewell ceremony in Winding up his final day in China Fairbanks, Alaska. after first visiting a Peking, Reagan flew south to this at a banquet given by Shanghai child care center and modest private teeming city of 12 million. Mayor Wang Daohan, Reagan said, residence at a commune on May Addressing more than 1 ,000 stu "My trip to China has been as impor· Day, the international workers· dents in a handpicked audience at tant and enlightening as any I've holiday. Fudan University, where a huge taken as pn:sident." As China prepared to celebrate statue of the late Mao Tse·tung Reagan also finally got an oppor· the two-day holiday. -

Frustration, Honor and Death in the Trilogy of Federico Garcia Lorca

(RJELAL) Research Journal of English Language and Literature Vol.4.Issue 3. 2016 A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal (July-Sept.) http://www.rjelal.com; Email:[email protected] RESEARCH ARTICLE FRUSTRATION, HONOR AND DEATH IN THE TRILOGY OF FEDERICO GARCIA LORCA BINDIYA RAHI SINGH JRF Research Scholar Guest Assistant Professor ABSTRACT In this research Paper, we will try to light on the theme of frustration honour and death in the plays of Federico Garcia Lorca who is the most eminent painter, singer of Andalusia Folklore and a poet of gipsy ballads. He was the master of Puppet theatre. His surrealistic style makes him the greatest dramatist among other contemporaries dramatist. It was his great writing for the Spanish Literature that he wrote rural trilogy as Blood wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba. Following these plays he knits the symbolical background with the Aristotelian BINDIYA RAHI concepts. His first play Blood Wedding is based on the theme of bloodshed and feud SINGH between two families which ends with thirst of murder to Bridegroom and Leonardo who belongs to the Felix Family and second one, Yerma is cry of a barren mother who murdered her husband in order to not satisfy her desire to be a mother and after abuse by her husband and last one The House Of Bernarda Alba ends with the death of honor of Adela by the orthodox cal attitude of Bernarda Alba. So this trilogy highlights the eminent features of his dramatic style overwhelming stresses and tensions throughout his entire plays along with, they have many symbolical songs in it. -

"Federico García Lorca's Blood Wedding (1932): Patriarchy's Tragic

Bonaddio, Federico. "Federico García Lorca’s Blood Wedding (1932): Patriarchy’s Tragic Flaws." Patriarchal Moments: Reading Patriarchal Texts. Ed. Cesare Cuttica. Ed. Gaby Mahlberg. : Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 163–170. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472589163.ch-021>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 05:58 UTC. Copyright © Cesare Cuttica, Gaby Mahlberg and the Contributors 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 20 Federico García Lorca’s Blood Wedding (1932): Patriarchy’s Tragic Flaws1 Federico Bonaddio [It’s wedding day somewhere in rural Andalusia, and the mother of the groom and father of the bride are sharing a private conversation.] MOTHER: That’s what I’m hoping for: grandchildren. (They sit.) FATHER: I want them to have plenty. This land needs hands that aren’t hired. You’re forever battling weeds, thistles, stones that appear from nowhere. And those hands should be the owners’ own, able to punish and master, to make the seed grow. You need a lot of sons. MOTHER: And a daughter or two! Men come and go like the wind! It’s in their nature to turn to knives and guns. Girls never venture out of the house. FATHER (Happily): I’m sure they’ll have both. MOTHER: My son will cover her well. He’s of good stock. His father could have had plenty of children with me. FATHER: I wish it could all happen in a day. -

Blood Wedding

Written by Federico Garcia Lorca, Directed by Dr. Keith Byron Kirk Study Guide The University of Houston School of Theatre and Dance is pleased to present this study guide arranged by the BFA Theatre Education majors. We hope that you i find the activities, photos, and script analysis enriching to your classroom expe- j rience and helpful as a companion to Blood Wedding. qblh Table of Contents Who Setting the Stage........................2 Who’s Who.................................3 Meet Lorca..................................4 What Opportunity Cost Game...........5 Blood Wedding Budgeting..........7 When A Light in Dark..........................9 A Wedding’s History................11 Where Cryptic or Beautiful?..............13 Committee Work Activity.......15 Why Themes of Blood Wedding........17 Altering a Lullaby ....................19 The Design of Life...................21 Mask Making Methods..............23 How Spaghetti Math...........................24 Gobo Creations.........................26 Use your QR scanning device or smartphone to learn more about The School of Theatre and Dance! 1 Setting The Stage The play begins with a scene between Federico Garcia Lorca and Margarita Xirgu. As they speak, the members of the La Barraca theatre troupe explain not only Lorca’s history but the critical views of his writing. Lorca begins writing the play “Blood Wedding.” The Mother and the Bridegroom, have a conversation about the Mother’s hatred of knives - the Bridegroom’s father and brother were murdered by members of the Felix family. They talk about the Bride- groom’s hope to be married to the Bride. After he exits, a Neighbor visits the Mother, revealing that the Bride was once the lover of Leonardo Felix. -

Teacher's Guide by Jerry Hawkins, Co-Founder of the Imagining Freedom Institute CARA MÍA THEATRE's Ursula, Or Let Yourself Go with the Wind

URSULA OR LET YOURSELF GO WITH THE WIND A PLAY WRITTEN AND PERFORMED BY FRIDA ESPINOSA-MüLLER Teacher's Guide by Jerry Hawkins, co-founder of The Imagining Freedom Institute CARA MÍA THEATRE'S Ursula, or Let Yourself Go with the Wind IN THIS TEACHER'S GUIDE YOU WILL FIND Pre-Show Guide Synopsis Investigation 1 Compares migration and immigration journeys and connects how they are similar. Activity: What is your family’s story? Mid-Show Guide Investigation 2 Borders are political boundaries, not human boundaries. Activity: What is a border? Post-Show Guide Investigation 3 Provides an opportunity for students to take inventory of their thoughts and emotions after watching the play while reflecting on our shared commonalities as diverse individuals. Activity: What are our connections? Biographies Cara Mía Theatre The Imagining Freedom Institute Frida Espinosa Müller (Playwright and Performer) Jerry Hawkins (Study Guide Author) Please be aware that all property and materials that you access before, during, or after watching the educational play Ursula or Let Yourself Go with the Wind, belong to Cara Mía Theatre Company with special permission given to Dallas ISD for distribution to its staff members and their students only. IF YOU ENCOUNTER ANY TECHNICAL ISSUES OR HAVE ANY QUESTIONS Email Cara Mía Theatre's Education and Community Action Coordinator Cheyenne Raquel Farley at [email protected] or call (214) 516 - 0706. EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS AT CARA MÍA THEATRE PRE-SHOW TEACHER'S GUIDE Grades 7- 12 URSULA OR LET YOURSELF GO WITH THE WIND PRE-SHOW TEACHER'S GUIDE / Grades 7 - 12 ABOUT THE PLAY With a minimal set, various puppets, and a performance rooted in movement, performer Frida Espinosa Müller transforms into over 10 characters to tell this story of child detention at the Southern border through the mind of a child. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

Eileen Stevens

"'LetEach Becone Aware" Founded 1957, Incorporated 1976 Volume XXXIX, Number 21 Monday, November 13, 1995 : First Copy lFree- University Senate Passes (quality of Teaching Propos1a, _w BY ENEILRYAN DE LA PENA departmental and university-wide for commuting students. order to gain student support. "I think [students] should at Statesman Editor training program. "There was a lot of least be able to understand their The University Senate . "In general, [the proposal] discussion," Mackin said, teachers, but-I think they should passed a. proposal at last 3. All teachers,- in will help the.students,-" said referring to the University Senate be strict on [enacting the Monday's'meeting that will undergraduate' course-both' Nicole Rosner, :Polity vice voting on the proposals, -last proposals]," said Natalie Jacobs, ultimately improve the quality of faculty and TA's-must speak, president and member of the Monday. "There were still a lot a sophomore. "A teacher can still teaching at Stony Brook, English at a level appropriate to Undergraduate Council, of people disagreeing with it.- be pretty, good at handling the according to James Mackin, classroom instruction or other referring to the TA's who do not The vote came up 37 to 5 in favor accent, but they must get their professor and' chair of the teaching duties. fluently speak English. "I don't of adopting them." Since the point across." Undergraduate Council. think it's fair that students go into proposals have been passed in the Sophia Campbell, a junior, Mackin, along 'with 4.' When possible, faculty classes while they can't Senate, they are now currently in -strongly agreed with the members of the Ad Hoc should be given credit for understand the TA." effect, said Mackin. -

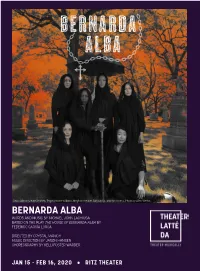

Bernarda Alba Program

BERNARDA ALBA Britta Ollmann, Kate Beahen, Regina Marie Williams, Meghan Kreidler, Sara Ochs, and Kim Kivens. Photo by Allen Weeks. BERNARDA ALBA WORDS AND MUSIC BY MICHAEL JOHN LACHIUSA BASED ON THE PLAY THE HOUSE OF BERNARDA ALBA BY FEDERICO GARCÍA LORCA DIRECTED BY CRYSTAL MANICH MUSIC DIRECTION BY JASON HANSEN CHOREOGRAPHY BY KELLI FOSTER WARDER JAN 15 - FEB 16, 2020 • RITZ THEATER Theater Latté Da’s re-imagined staging of the beloved opera returns. Painting: Bonjour Tristesse, Nicholas Harper LA BOHÈME MUSIC BY GIACOMO PUCCINI LIBRETTO BY LUIGI ILLICA AND GUISEPPE GIACOSA NEW ORCHESTRATION BY JOSEPH SCHLEFKE DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY ERIC MCENANEY In memory of John Hemann MAR 11 - APR 26, 2020 • RITZ THEATER • TICKETS ON SALE NOW Words and music by Michael John LaChiusa Based on the play The House of Bernarda Alba by Federico García Lorca THE COMPANY PRODUCTION TEAM * Bernarda Alba ..................................... Regina Marie Williams Director ...................................................................................... Crystal Manich † Music Director ..................................................................... Jason Hansen Angustias .............................................................................. Kate Beahen ** Choreographer .................................................... Kelli Foster Warder * Magdalena ................................................................... Nora Montañez Assistant Director ..................................................... Jillian Robertson -

Melia Bensussen

MELIA BENSUSSEN Emerson College (home) 120 Boylston Avenue 132 Sewall Avenue, #1 Boston, MA 02116 Brookline, MA 02446 (617) 824-8368 (617) 739-2240 home [email protected] (617) 461-4835 cell PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2008 – present Chair, Department of Performing Arts Associate Professor Emerson College, Boston, MA 2007 – 2008 Interim Chair, Department of Performing Arts Associate Professor Emerson College 2006 – 2007 Associate Professor, Emerson College Producing Director, Emerson Stage 2000 – 2006 Assistant Professor, Emerson College Producing Director, Emerson Stage Emerson College Awarded the 2003-04 Norman and Irma Mann Stearns Distinguished Faculty Award 1986 – present Free-Lance Theatre Director Over 80 productions in New York City and nationwide. Winner of the 1999 Obie for Excellence in Directing 1996 - 2000 Head of Directing, Assistant Professor, SMU Responsible for creating and running MFA in Directing program. Received NAST accreditation for the MFA program within two years. Recipient of the Dean’s Prize, 1997 and 1999. 1998 - 2000 Artistic Consultant, Shakespeare Festival of Dallas Forged partnership between SMU and the Shakespeare Festival. Collaborated on the Festival’s restructuring, created a five-year plan, as well as consulting on season scheduling, fundraising, educational programs, casting and marketing. 1997 - 1998 Artistic Associate, San Jose Repertory Theatre New Play Festival Artistic Director. Selected and dramaturged new plays, directed workshops, and created a new marketing strategy which succeeded in doubling attendance. 1990 - 1993 Associate Artist, New York Shakespeare Festival Produced and directed a season of new adaptations and translations, including works by Brecht, Euripides, Kroetz; translated by Regina Taylor, Arthur Giron, and others. 1986 - 1990 Associate Director, Festival Latino in New York, NYSF The Festival produced companies from throughout Latin America and Spain. -

Lorca's Blood Wedding

8-10 September 2014- Istanbul, Turkey 392 Proceedings of SOCIOINT14- International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities LORCA’S BLOOD WEDDING: A MANIFESTATION OF SPANISH FOLKLORE Saeed Yazdani 1* Mohammadreza Shahbazi 2 Mozdeh Ghazi 3 1Department of English Literature, Bushehr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bushehr, IRAN, [email protected] *Corresponding author 2Department of Dramatic Literature, Bushehr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bushehr, IRAN, [email protected] 3M.A. Department of Dramatic Literature, Bushehr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bushehr, IRAN [email protected] Abstract Culture has been an important factor in the production of literary works throughout the world. The Spanish playwright Federico García Lorca maintained a lifelong interest in the music and folklore of Spain, a fascination that heavily influenced one of his most acclaimed tragedies, Blood Wedding. The repressive social norms of the rural town are often contrasted with the raw, emotional state of nature in which the characters desire to live. In Lorca's countryside, heritage and violence are inextricably linked. The shallow and restrictive town, then, can be seen as a response and overreaction to the chaotic, bleak fate that man faces in nature. In approaching Blood Wedding, we should also be aware of the many cultural influences that fed into the play, notably the dramatist‘s familiarity with classical, flamenco and traditional Spanish music, and with Greek tragedy. All of them combined to transform a real life event into high art. The play resonates with an incredible passionate, tragic, beautiful love. The whole idea of the inevitability of love and death, which is present at the core of the Spanish culture, beats at the heart of the play, so strongly and so intensely. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9412044 Norms and strategies in the English translations of Federico Garcfa Lorca’s “Bodas de sangre” Robie-Theunen, Nicole Susanne, Ph.D. -

BLOOD WEDDING Although It's the Title of a Rock and Notre Dame's Own 'Theater-In-The Roll Song, "Eight Days a Week" Is Also Round'

Little Theatre Presents . BLOOD WEDDING Although it's the title of a rock and Notre Dame's own 'theater-in-the roll song, "Eight Days A Week" is also round'. The theater is located in the the motto of Notre Dame's Little Thea- new Humanities Center, and is one that ter. A professional perform~ce of any is worthy of any Broadway production. sort demands a rigorous schedule, but The stage is equipped to handle any this year's choice is even more exacting. and all lighting cues. The intimacy that Blood Wedding by Fredrico Garcia the play demands is enhanced by the Lorca, is a spontaneous and simple in- size of the theater, as it is small and can tegration of poetry and drama. The accommodate only a few. The audience moments of the play' s greatest dramatic easily gets the feeling that they are a- intensity are in verse. lone, viewing a slice of life. Blood Wedding was inspired by a The participants in this exacting play new~paper account of an incident al- are : most identical with the plot of the play, Bridegroom .......... Joseph Barone which took place in Almeria. The plot Mother . Constance Cucchiara is simply this: the bridegroom plans Neighbor .... ..... Veronica Abelli to marry, but the bride is in love with Leonardo's Mother-in-Law ......... another whose name is Leonardo. He Claudia Hart in turn is married to the bride's cousin. Leonardo's Wife ... .... Anne Young C a st reh earses Blood Wedding scene, C. C ucchia ra , G . Altamari, J. Barone, R.