Mudfish (Neochanna Galaxiidae) Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Habitat for Canterbury Freshwater Fish, Kōura/Kēkēwai and Kākahi

CRITICAL HABITAT FOR CANTERBURY FRESHWATER FISH, KŌURA/KĒKĒWAI AND KĀKAHI REPORT PREPARED FOR CANTERBURY REGIONAL COUNCIL BY RICHARD ALLIBONE WATERWAYS CONSULTING REPORT NUMBER: 55-2018 AND DUNCAN GRAY CANTERBURY REGIONAL COUNCIL DATE: DECEMBER 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Aquatic habitat in Canterbury supports a range of native freshwater fish and the mega macroinvertebrates kōura/kēkēwai (crayfish) and kākahi (mussel). Loss of habitat, barriers to fish passage, water quality and water quantity issues present management challenges when we seek to protect this freshwater fauna while providing for human use. Water plans in Canterbury are intended to set rules for the use of water, the quality of water in aquatic systems and activities that occur within and adjacent to aquatic areas. To inform the planning and resource consent processes, information on the distribution of species and their critical habitat requirements can be used to provide for their protection. This report assesses the conservation status and distributions of indigenous freshwater fish, kēkēwai and kākahi in the Canterbury region. The report identifies the geographic distribution of these species and provides information on the critical habitat requirements of these species and/or populations. Water Ways Consulting Ltd Critical habitats for Canterbury aquatic fauna Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Methods .............................................................................................................................................. -

A Global Assessment of Parasite Diversity in Galaxiid Fishes

diversity Article A Global Assessment of Parasite Diversity in Galaxiid Fishes Rachel A. Paterson 1,*, Gustavo P. Viozzi 2, Carlos A. Rauque 2, Verónica R. Flores 2 and Robert Poulin 3 1 The Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, P.O. Box 5685, Torgarden, 7485 Trondheim, Norway 2 Laboratorio de Parasitología, INIBIOMA, CONICET—Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Quintral 1250, San Carlos de Bariloche 8400, Argentina; [email protected] (G.P.V.); [email protected] (C.A.R.); veronicaroxanafl[email protected] (V.R.F.) 3 Department of Zoology, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-481-37-867 Abstract: Free-living species often receive greater conservation attention than the parasites they support, with parasite conservation often being hindered by a lack of parasite biodiversity knowl- edge. This study aimed to determine the current state of knowledge regarding parasites of the Southern Hemisphere freshwater fish family Galaxiidae, in order to identify knowledge gaps to focus future research attention. Specifically, we assessed how galaxiid–parasite knowledge differs among geographic regions in relation to research effort (i.e., number of studies or fish individuals examined, extent of tissue examination, taxonomic resolution), in addition to ecological traits known to influ- ence parasite richness. To date, ~50% of galaxiid species have been examined for parasites, though the majority of studies have focused on single parasite taxa rather than assessing the full diversity of macro- and microparasites. The highest number of parasites were observed from Argentinean galaxiids, and studies in all geographic regions were biased towards the highly abundant and most widely distributed galaxiid species, Galaxias maculatus. -

President Postal Address: PO Box 312, Ashburton 7740 Phone: 03

GENERAL SERVICE GROUPS Altrusa Altrusa Foot Clinic for Senior Citizens Contact: Rosemary Moore – President Contact: Mary Harrison – Coordinator Postal Address: P. O. Box 312, Ashburton Phone: 03 308 8437 or 021 508 543 7740 Email: [email protected] Phone: 03 308 3442 or 0274396793 Email: [email protected] Contact: Helen Hooper – Secretary Phone: 03 3086088 or 027 421 3723 Email: [email protected] Contact: Beverley Gellatly – Treasurer Phone: 03 308 9171 or 021 130 3801 Email: [email protected] Ashburton District Family History Group Ashburton Returned Services Association Contact: Shari - President 03 302 1867 Contact: Patrice Ansell – Administrator Contact: Rita – Secretary 03 308 9246 Address: 12-14 Cox Street, Ashburton Address: Heritage Centre, West Street, PO Box 341, Ashburton 7740 Ashburton Phone: 03 308 7175 Hours: 1-4pm Mon-Wed-Fri Email: [email protected] 10-1pm Saturday Closed Public Holidays Ashburton Toastmasters Club Ashburton Woodworkers Contact: Matt Contact: Bruce Ferriman - President Address: C/- RSA Ashburton, Doris Linton Address: 37a Andrew Street, Ashburton 7700 Lounge, Phone: 027 425 5815 12 Cox Street, Ashburton 7700 Email: [email protected] Phone: 027 392 4586 Website: www.toastmasters.org CanInspire Community Energy Action Contact: Kylie Curwood – National Coordinator Contact: Michael Begg – Senior Energy Address: C/- Community House Mid Advisor Canterbury Address: PO Box 13759, Christchurch 8141 44 Cass Street, Ashburton 7700 199 Tuam Street, Christchurch Phone: 03 3081237 -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

2426 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 63 MILITARY AREA No. 10 (CHRISTCHVRCH)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 10 (CHRISTCHURCH)-contin-ueJ, 138223 Oliver, James, photo-engraver, 33 Worcester St., Christ 130267 Parish, Thomas John Alan, civil servant, 86 Elizabeth St., church. Timaru. 433425 Ollerenshaw, Herbert James, deer-culler, 94 Mathieson's 402677 Parker, George Henry, dairy-farmer and commercial fruit Rd., Christchurch. grower, Leithfield. 241509 Olorenshaw, Charles Maxwell, farm hand, Anio, Waimate. 427272 Parker, Noel Groves, carpenter, 30 Clyde St., Christchurch 238851 O'Loughlin, Patrick, drover, St. Andrews. C.l. 427445 Olsen, Alan, oil worker, 13 Brittan Tee., Lyttelton. 378368 Parkin, Charles Edward, farm hand, Bankside. 289997 O'Malley, Clifford, office-assistant, 39 Travers St., Christ 230363 Parkin, Eric Patrick, clerk, 419 Madras St., St. Albans, church. Christchurch N. 1. 134366 O'Neil, Maurice Arthur, engineer, 39 Draper St., Richmond, 377490 Parkin, Morris John, grocer, 210 Richmond Tee., New Christchurch. Brighton, Christchurch. 275866 O'Neil, Owen Hepburn, chainman, 278 Bealey Ave., 297032 Parlane, Ashley Bruce, shop-assistant, 54 Cranford St., Christchurch C. 1. St. Albans, Christchurch. 416689 O'Neill, Francis William, farm hand, Prebbleton, 403080 Parnell, Lloyd John, driver, 191 Hills Rd., Christchurch. 281268 O'Neill, John, farm hand, Kaiapoi. 237171 Parr, Archibald James, farmer, Brooklands, Geraldine. 431878 O'Neill, John Albert, labourer, 58 Mauncell St., Woolston, 240180 Parry, John Pryce, farm hand, Southburn, Timaru. Christchurch. 042301 Parsons, Robert Thomas, shepherd, care of H. Ensor, 225912 O'Neill, Leonard Kendall, cook, 12 Ollivier's Rd., Linwood, '' Rakahuri,'' Rangiora. Christchurch, 186940 Parsonson, Geoffrey Scott, farm hand, care of Mr. D. McLeod, 279267 O'Neill, William James, 11 Southey St., Sydenham, Christ P.O. -

Download Full Article 1.0MB .Pdf File

Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria 57( I): 143-165 ( 1998) 1 May 1998 https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1998.57.08 FISHES OF WILSONS PROMONTORY AND CORNER INLET, VICTORIA: COMPOSITION AND BIOGEOGRAPHIC AFFINITIES M. L. TURNER' AND M. D. NORMAN2 'Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, PO Box 1379,Townsville, Qld 4810, Australia ([email protected]) 1Department of Zoology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic. 3052, Australia (corresponding author: [email protected]) Abstract Turner, M.L. and Norman, M.D., 1998. Fishes of Wilsons Promontory and Comer Inlet. Victoria: composition and biogeographic affinities. Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria 57: 143-165. A diving survey of shallow-water marine fishes, primarily benthic reef fishes, was under taken around Wilsons Promontory and in Comer Inlet in 1987 and 1988. Shallow subtidal reefs in these regions are dominated by labrids, particularly Bluethroat Wrasse (Notolabrus tet ricus) and Saddled Wrasse (Notolabrus fucicola), the odacid Herring Cale (Odax cyanomelas), the serranid Barber Perch (Caesioperca rasor) and two scorpidid species, Sea Sweep (Scorpis aequipinnis) and Silver Sweep (Scorpis lineolata). Distributions and relative abundances (qualitative) are presented for 76 species at 26 sites in the region. The findings of this survey were supplemented with data from other surveys and sources to generate a checklist for fishes in the coastal waters of Wilsons Promontory and Comer Inlet. 23 I fishspecies of 92 families were identified to species level. An additional four species were only identified to higher taxonomic levels. These fishes were recorded from a range of habitat types, from freshwater streams to marine habitats (to 50 m deep). -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

Summary of Decisions Requested Report PROVISION ORDER*

PROPOSED VARIATION 2 TO THE PROPOSED CANTERBURY LAND AND WATER REGIONAL PLAN Summary of Decisions Requested Report PROVISION ORDER* Notified Saturday 13 December 2014 Further Submissions Close 5:00pm Friday 16 January 2015 * Please Note There is an Appendix B To This Summary That Contains Further Submission Points From The Proposed Canterbury Land And Water Regional Plan That Will Be Considered As Submissions To Variation 2. For Further Information Please See Appendix B. Report Number : R14/106 ISBN: 978-0-908316-05-2 (hard copy) ISBN: 978-0-908316-06-9 (web) ISBN: 978-0-908316-07-6 (CD) SUMMARY OF DECISIONS REQUESTED GUIDELINES 1. This is a summary of the decisions requested by submitters. 2. Anyone making a further submission should refer to a copy of the original submission, rather than rely solely on the summary. 3. Please refer to the following pages for the ID number of Submitters and Addresses for Service. 4. Environment Canterbury is using a new database system to record submissions, this means that the Summary of Decisions Requested will appear different to previous versions. Please use the guide below to understand the coding on the variation. Plan Provision tells Point ID is now you where in the the “coding “of plan the submission Submitter ID is the submission point is coded to now a 5 Digit point Number Sub ID Organisation Details Contact Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Town/City Post Code 51457 Senior Policy Advisor Mr Lionel Hume PO Box 414 Ashburton 7740 Federated Farmers Combined Canterbury Branch 52107 -

Ashburton Water Management Zone Committee Agenda

ASHBURTON WATER MANAGEMENT ZONE COMMITTEE AGENDA A Meeting of the Ashburton Water Management Zone Committee will be held as follows: DATE: Tuesday 25 August 2020 TIME: 1:00 pm VENUE: Council Chamber 137 Havelock Street Ashburton MEETING CALLED BY: Hamish Riach, Chief Executive, Ashburton District Council Stefanie Rixecker, Chief Executive, Environment Canterbury ATTENDEES: Mr Chris Allen Mrs Angela Cushnie Ms Genevieve de Spa Mr Cargill Henderson Mr Bill Thomas Mr John Waugh Mr Arapata Reuben (Te Ngai Tuahuriri Runanga) Mr Karl Russell (Te Runanga o Arowhenua) Mr Les Wanhalla (Te Taumutu Runanga) Mr Brad Waldon-Gibbons (Tangata Whenua Facilitator) Councillor Stuart Wilson (Ashburton District Council) Councillor Ian Mackenzie (Environment Canterbury) Mayor Neil Brown (Ashburton District Council) Zone Facilitator Committee Advisor Tangata Whenua Facilitator Dave Moore Carol McAtamney Brad Waldon-Gibbons Tel: 027 604 3908 Tel: 307 9645 Tel: 027 313 4786 [email protected] [email protected] brad.waldon- Environment Canterbury Ashburton District Council [email protected] Environment Canterbury 4 Register of Interests Representative’s Name and Interest Chris Allen Farm owner of sheep, beef, lambs, crop Water resource consents to take water from tributary of Ashburton River and shallow wells National board member Federated Farmers of New Zealand with responsibility for RMA, water and biodiversity Member of Ashburton River Liaison Group Neil Brown Mayor Acton Irrigation Limited - Director Irrigo Centre Limited - Director Acton -

Aspects of the Phylogeny, Biogeography and Taxonomy of Galaxioid Fishes

Aspects of the phylogeny, biogeography and taxonomy of galaxioid fishes Jonathan Michael Waters, BSc. (Hons.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, / 2- Oo ( 01 f University of Tasmania (August, 1996) Paragalaxias dissim1/is (Regan); illustrated by David Crook Statements I declare that this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published o:r written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying for two years following the date this statement is signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed Summary This study used two distinct methods to infer phylogenetic relationships of members of the Galaxioidea. The first approach involved direct sequencing of mitochondrial DNA to produce a molecular phylogeny. Secondly, a thorough osteological study of the galaxiines was the basis of a cladistic analysis to produce a morphological phylogeny. Phylogenetic analysis of 303 base pairs of mitochondrial cytochrome b _supported the monophyly of Neochanna, Paragalaxias and Galaxiella. This gene also reinforced recognised groups such as Galaxias truttaceus-G. auratus and G. fasciatus-G. argenteus. In a previously unrecognised grouping, Galaxias olidus and G. parvus were united as a sister clade to Paragalaxias. In addition, Nesogalaxias neocaledonicus and G. paucispondylus were included in a clade containing G. -

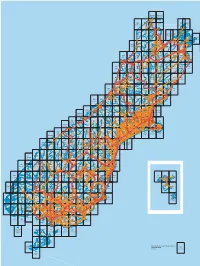

Boundaries, Sheet Numbers and Names of Nztopo50 Series 1:50

BM24ptBN24 BM25ptBN25 Cape Farewell Farewell Spit Puponga Seaford BN22 BN23 Mangarakau BN24 BN25 BN28 BN29ptBN28 Collingwood Kahurangi Point Paturau River Collingwood Totaranui Port Hardy Cape Stephens Rockville Onekaka Puramahoi Totaranui Waitapu Takaka Motupipi Kotinga Owhata East Takaka BP22 BP23 BP24 Uruwhenua BP25 BP26ptBP27 BP27 BP28 BP29 Marahau Heaphy Beach Gouland Downs Takaka Motueka Pepin Island Croisilles Hill Elaine Te Aumiti Endeavour Inlet Upper Kaiteriteri Takaka Bay (French Pass) Endeavour Riwaka Okiwi Inlet ptBQ30 Brooklyn Bay BP30 Lower Motueka Moutere Port Waitaria Motueka Bay Cape Koamaru Pangatotara Mariri Kenepuru Ngatimoti Kina Head Oparara Tasman Wakapuaka Hira Portage Pokororo Rai Harakeke Valley Karamea Anakiwa Thorpe Mapua Waikawa Kongahu Arapito Nelson HavelockLinkwater Stanley Picton BQ21ptBQ22 BQ22 BQ23 BQ24 Brook BQ25 BQ26 BQ27 BQ28 BQ29 Hope Stoke Kongahu Point Karamea Wangapeka Tapawera Mapua Nelson Rai Valley Havelock Koromiko Waikawa Tapawera Spring Grove Little Saddle Brightwater Para Wai-iti Okaramio Wanganui Wakefield Tadmor Tuamarina Motupiko Belgrove Rapaura Spring Creek Renwick Grovetown Tui Korere Woodbourne Golden Fairhall Seddonville Downs Blenhiem Hillersden Wairau Hector Atapo Valley BR20 BR21 BR22 BR23 BR24 BR25 BR26 BR27 BR28 BR29 Kikiwa Westport BirchfieldGranity Lyell Murchison Kawatiri Tophouse Mount Patriarch Waihopai Blenheim Seddon Seddon Waimangaroa Gowanbridge Lake Cape Grassmere Foulwind Westport Tophouse Sergeants Longford Rotoroa Hill Te Kuha Murchison Ward Tiroroa Berlins Inangahua -

Flood Plain Lower Ringarooma River Ramsar Site Ecological Character Description

Flood Plain Lower Ringarooma River Ramsar Site Ecological Character Description March 2012 Citation: Newall, P.R. and Lloyd, L.N. 2012. Ecological Character Description for the Flood Plain Lower Ringarooma River Ramsar Site. Lloyd Environmental Pty Ltd Report (Project No: LE0944) to the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC), Australian Government. Lloyd Environmental, Syndal, Victoria, 2nd March 2012. Copyright © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2012. The Ecological Character Description for the Flood Plain Lower Ringarooma River Ramsar site is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons By Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ This report should be attributed as ‘Ecological Character Description for the Flood Plain Lower Ringarooma River Ramsar site, Commonwealth of Australia 2012’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Acknowledgements: • Chris Bobbi, Senior Water Environment Officer, Water Assessment Branch, Water Resources Division, Department of Primary Industries and Water (DPIW) • Sally Bryant, Manager Threatened Species Section, Biodiversity Conservation