Re-Launching the Dream Weapon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hidden Hydrology COIL’S ‘Lost Rivers’ Sessions 1995-1996

Hidden Hydrology COIL’s ‘Lost Rivers’ Sessions 1995-1996 {Fan Curated EP} COIL - The ‘Lost Rivers’ Sessions 1995-1996 {Fan Curated EP} Lost Rivers of London Succour Version [DAT Master]. Untitled Instrumental #6 [DAT #30] 5 takes from the BLD Sessions 1995-1996. London’s Lost Rivers [Take #2 - vocals] Rough vocal track w. minimal backing mix. Lost Rivers of London [Take #1] Early version with vocals. Crackanthorpe; Sunrise Reading from Vignettes by Phil Barrington. London’s Lost Rivers [Take #1] Initial studio version with abrupt ending. [Cover Version] By The Psychogeographical Commission. Hidden Hydrology COIL's 'Lost Rivers' Studio Sessions COIL's "Lost Rivers" sessions were recorded during the Winter period of December 1995- February 1996 at COIL's own "Slut's Hole" studio in London. The day-long sessions were part of what ultimately became the "A Thousand Lights In A Darkened Room" album (at least as far as the vinyl pressing of that album went), though were apparently very rushed recordings (Jhonn later claimed that the full vocal version was written and recorded in one day to meet the “Succour” compilation deadline - Jhonn’s wraparound vocals were not redone for the BLD track). Around this winter time Jhonn Balance received a fax from David Tibet containing evocative passages from the Crackanthorpe "Vignettes" journal, originally published 100 years earlier (1896). Jhonn loved the sections he read and swiftly used passages as lyrics for the recording sessions to meet the Succour deadline (lifting text from the ‘On Chelsea Embankment’ and “In Richmond Park” sections of the small book). At the very same time as recording this track, the official (and long-awaited) 2nd Edition of the Nicholas Barton book called "The Lost Rivers of London" appeared in the bookshops of the city. -

Drone Records Mailorder-Newsflash MARCH / APRIL 2008

Drone Records Mailorder-Newsflash MARCH / APRIL 2008 Dear Droners & Lovers of thee UN-LIMITED music! Here are our new mailorder-entries for March & April 2008, the second "Newsflash" this year! So many exciting new items, for example mentioning only the great MUZYKA VOLN drone-compilation of russian artists, the amazing 4xLP COIL box, a new LP by our beloved obscure-philosophist KALLABRIS, deep meditation-drones by finlands finest HALO MANASH, finally some new releases by URE THRALL, and the four new Drone EPs on our own label are now out too!! Usually you find in our listing URLs of labels or artists where its often possible to listen to extracts of the releases online. LABEL-NEWS: We are happy to take pre-orders for: OÖPHOI - Potala 10" VINYL Substantia Innominata SUB-07 Two long tracks of transcendental drones by the italian deep-ambient master, the first EVER OÖPHOI-vinyl!! "Dedicated to His Holiness The Dalai Lama and to Tibet's struggle for freedom." Out in a few weeks! Soon after that we have big plans for the 10"-series with releases by OLHON ("Lucifugus"), HUM ("The Spectral Ship"), and VOICE OF EYE, so watch out!!! As always, pre-orders & reservations are possible. You also may ask for any new release from the more "experimental" world that is not listed here, we are probably able to get it for you. About 80% of the titles listed are in stock, others are backorderable quickly. The FULL mailorder-backprogramme is viewable (with search- & orderfunction) on our website www.dronerecords.de. Please send your orders & all communication to: [email protected] PLEASE always mention all prices to make our work on your orders easier & faster and to avoid delays, thanks a lot ! (most of the brandnew titles here are not yet listed in our database on the website, but will be soon, so best to order from this list in reply) BUILD DREAMACHINES THAT HELP US TO WAKE UP! with best drones & dark blessings from BarakaH 1 AARDVARK - Born CD-R Final Muzik FMSS06 2007 lim. -

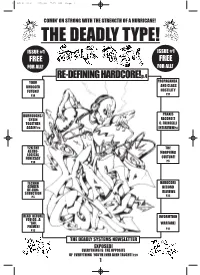

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1 COMINÕ ON STRONG WITH THE STRENGTH OF A HURRICANE! THE DEADLY TYPE! ISSUE #1 ISSUE #1 FREE FREE FOR ALL!L FOR ALL!L RE-DEFINING HARDCORE!p.4 YOUR PROPAGANDA DRUGGED AND CLASS FUTURE! HOSTILITY P.14 P.11 BURROUGHS/ PRAXIS GYSIN RECORD'S TOGETHER C. FRINGELLI AGAIN! P.6 INTERVIEWP.8 Y2K:THE THE ASTRO- MORPHING LOGICAL FORECAST CULTURE! P.10 P.5 TECHNO HARDCORE GENDER RECORD DE-CON- STRUCTION REVIEWS P.5 P.16 READ BEFORE INFORMTION YOU GO...A "JAIL WARFARE! PRIMER! P.12 P.13 THE DEADLY SYSTEMS NEWSLETTER EXPOSED! EVERYTHING IS THE OPPOSITE OF EVERYTHING YOU'VE EVER BEEN TAUGHT! P.29 1 DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 2 money. So you could say that the rave scene was truly assimilated on just about all fronts by the mainstream. This WHY THE aggravated a problem of mis-concep- tion for the music itself . Most people being introduced to Hardcore had no idea about the ideas surrounding it-or DEADLY that there even were any! To most peo- ple, even a few making music they claimed was “hardcore”, it was just fast, noizy, and supposed to piss you off. This is retarded. Nothing can be further TYPE? from the truth, and that is why “The Deadly Type” exists today, to re-define Hardcore. Firstly, “RE” as to do it again, -by Deadly Buda as people are not even aware of it’s influences, history or forgot the entire The original reason for this social context. -

Coil Another Brown World / Baby Food Mp3, Flac, Wma

Coil Another Brown World / Baby Food mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Another Brown World / Baby Food Country: Belgium Released: 2017 Style: Industrial, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1468 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1195 mb WMA version RAR size: 1667 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 169 Other Formats: MP4 AHX WMA AC3 MMF VOC MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits Another Brown World A Producer [Produced By], Mixed By – CoilRecorded By – Danny HydeWritten-By – John Balance, Peter Christopherson Baby Food B Performer [Essentials] – Danny HydePerformer [Fundamentals] – Peter ChristophersonPerformer [Vibrant Rays Of Spiritual Psychosis] – John BalanceWritten-By, Performer [Performed By] – Coil Companies, etc. Recorded At – Threshold House Pressed By – Record Industry – 9543 Notes Side A: Recorded by Danny Hyde at Threshold House, London, Summer 1989. Vocals recorded at the Animist Monastery situated at the Summit of Mount Popa in Pagan, Burma. First issued 1989 on Myths 4 • Sinople Twilight In Çatal Hüyük compilation. Side B issued 1993 on Chaos In Expansion compilation. Both tracks were commissioned by Sub Rosa. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5411867114437 Matrix / Runout (Side A, stamped): 9543 2A SRV443 Matrix / Runout (Side B, stamped): 9543 2B SRV443 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SRV443 Coil Another Brown World / Baby Food (LP, Comp) Sub Rosa SRV443 Belgium 2017 Related Music albums to Another Brown World / Baby Food by Coil 1. Coil - The Restitution Of Decayed Intelligence 2. Coil - Panic / Tainted Love 3. Danny Peppermint - One More Time / La Dee Dah 4. Blue Jay Boys - My Baby / Brown Skin Mama 5. Coil - Horse Rotorvator 6. -

Джоð½ Зоñ€Ð½ ÐлÐ

Джон Зорн ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) The Big Gundown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-big-gundown-849633/songs Spy vs Spy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spy-vs-spy-249882/songs Buck Jam Tonic https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/buck-jam-tonic-2927453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/six-litanies-for-heliogabalus- Six Litanies for Heliogabalus 3485596/songs Late Works https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/late-works-3218450/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/templars%3A-in-sacred-blood- Templars: In Sacred Blood 3493947/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/moonchild%3A-songs-without-words- Moonchild: Songs Without Words 3323574/songs The Crucible https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-crucible-966286/songs Ipsissimus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ipsissimus-3154239/songs The Concealed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-concealed-1825565/songs Spillane https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spillane-847460/songs Mount Analogue https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mount-analogue-3326006/songs Locus Solus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/locus-solus-3257777/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/at-the-gates-of-paradise- At the Gates of Paradise 2868730/songs Ganryu Island https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ganryu-island-3095196/songs The Mysteries https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-mysteries-15077054/songs A Vision in Blakelight -

Catalog INTERNATIONAL

اﻟﻤﺆﺗﻤﺮ اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻤﻲ اﻟﻌﺸﺮون ﻟﺪﻋﻢ اﻻﺑﺘﻜﺎر ﻓﻲ ﻣﺠﺎل اﻟﻔﻨﻮن واﻟﺘﻜﻨﻮﻟﻮﺟﻴﺎ The 20th International Symposium on Electronic Art Ras al-Khaimah 25.7833° North 55.9500° East Umm al-Quwain 25.9864° North 55.9400° East Ajman 25.4167° North 55.5000° East Sharjah 25.4333 ° North 55.3833 ° East Fujairah 25.2667° North 56.3333° East Dubai 24.9500° North 55.3333° East Abu Dhabi 24.4667° North 54.3667° East SE ISEA2014 Catalog INTERNATIONAL Under the Patronage of H.E. Sheikha Lubna Bint Khalid Al Qasimi Minister of International Cooperation and Development, President of Zayed University 30 October — 8 November, 2014 SE INTERNATIONAL ISEA2014, where Art, Science, and Technology Come Together vi Richard Wheeler - Dubai On land and in the sea, our forefathers lived and survived in this environment. They were able to do so only because they recognized the need to conserve it, to take from it only what they needed to live, and to preserve it for succeeding generations. Late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan viii ZAYED UNIVERSITY Ed unt optur, tet pla dessi dis molore optatiist vendae pro eaqui que doluptae. Num am dis magnimus deliti od estem quam qui si di re aut qui offic tem facca- tiur alicatia veliqui conet labo. Andae expeliam ima doluptatem. Estis sandaepti dolor a quodite mporempe doluptatus. Ustiis et ium haritatur ad quaectaes autemoluptas reiundae endae explaboriae at. Simenis elliquide repe nestotae sincipitat etur sum niminctur molupta tisimpor mossusa piendem ulparch illupicat fugiaep edipsam, conecum eos dio corese- qui sitat et, autatum enimolu ptatur aut autenecus eaqui aut volupiet quas quid qui sandaeptatem sum il in cum sitam re dolupti onsent raeceperion re dolorum inis si consequ assequi quiatur sa nos natat etusam fuga. -

Throbbing Gristle 40Th Anniv Rough Trade East

! THROBBING GRISTLE ROUGH TRADE EAST EVENT – 1 NOV CHRIS CARTER MODULAR PERFORMANCE, PLUS Q&A AND SIGNING 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEBUT ALBUM THE SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Throbbing Gristle have announced a Rough Trade East event on Wednesday 1 November which will see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti in conversation, and Chris Carter performing an improvised modular set. The set will be performed predominately on prototypes of a brand new collaboration with Tiptop Audio. Chris Carter has been working with Tiptop Audio on the forthcoming Tiptop Audio TG-ONE Eurorack module, which includes two exclusive cards of Throbbing Gristle samples. Chris Carter has curated the sounds from his personal sonic archive that spans some 40 years. Card one consists of 128 percussive sounds and audio snippets with a second card of 128 longer samples, pads and loops. The sounds have been reworked and revised, modified and mangled by Carter to give the user a unique Throbbing Gristle sounding palette to work wonders with. In addition to the TG themed front panel graphics, the module features customised code developed in collaboration with Chris Carter. In addition, there will be a Throbbing Gristle 40th Anniversary Q&A event at the Rough Trade Shop in New York with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, date to be announced. The Rough Trade Event coincides with the first in a series of reissues on Mute, set to start on the 40th anniversary of their debut album release, The Second Annual Report. On 3 November 2017 The Second Annual Report, presented as a limited edition white vinyl release in the original packaging and also on double CD, and 20 Jazz Funk Greats, on green vinyl and double CD, will be released, along with, The Taste Of TG: A Beginner’s Guide to Throbbing Gristle with an updated track listing that will include ‘Almost A Kiss’ (from 2007’s Part Two: Endless Not). -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 You Sound Like A Broken Record: A practice led interrogation of the ontological resonances of vinyl record culture. Paul G Nataraj PhD – Creative and Critical Practice University of Sussex December 2016 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature………………………………………………………………………………… 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is dedicated to my Dad, Dr. V. Nataraj. Thank you to my family Mum, Peter, Sophie and Claire. But especially my wonderful wife Sarah, without you I could never have finished this. Your kindness and patience are a constant inspiration. I’d also like to shout out my Longanese brother David Boon, for his constant belief in the music. Thanks also to my supervisors, Dr. Martin Spinelli and Professor Michael Bull. You have been impeccable in your support and advice, and your skill as teachers and mentors is second to none. -

Journeys of the Beat Generation

My Witness Is the Empty Sky: Journeys of the Beat Generation Christelle Davis MA Writing (by thesis) 2006 Certificate of Authorship/Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all the information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate 11 Acknowledgements A big thank you to Tony Mitchell for reading everything and coping with my disorganised and rushed state. I'm very appreciative of the Kerouac Conference in Lowell for letting me attend and providing such a unique forum. Thank you to Buster Burk, Gerald Nicosia and the many other Beat scholars who provided some very entertaining e mails and opinions. A big slobbering kiss to all my beautiful friends for letting me crash on couches all over the world and always ringing, e mailing or visiting just when I'm about to explode. Thanks Andre for making me buy that first copy of On the Road. Thank you Tim for the cups of tea and hugs. I'm very grateful to Mum and Dad for trying to make everything as easy as possible. And words or poems are not enough for my brother Simon for those silly months in Italy and turning up at that conference, even if you didn't bother to wear shoes. -

Coil Porto Mp3, Flac, Wma

Coil Porto mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Porto Country: Portugal Released: 2006 Style: Abstract, Drone, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1114 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1199 mb WMA version RAR size: 1153 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 651 Other Formats: RA XM AA MP1 WMA AC3 WAV Tracklist 1 Blue Rats 18:14 2 Triple Sun 12:56 3 Radio Westin 13:32 4 Drip Drop 10:04 5 The First Five Minutes After Death 11:24 Credits Performer [Uncredited] – Ossian Brown, Peter Christopherson, Thighpaulsandra Notes NOTE: this release is sourced from an mp3. This is the "Pink" version of this release. Limited to 100 copies. An "authorised bootleg" recording of Coil's live performance on June 21st 2003 in Porto, Portugal. The package, contained within a clear plastic wallet, includes one audio CD and one clear plastic CD-size disc with text printed onto it. Also included are printed acetates displaying biological micrographs in colour, and printed semi-transparent paper inserts containing single colour micrograph prints (these single colour prints determining the colour version of each individual item). The 6 editions, each limited to 100 copies, are: white, black, red, blue, pink, purple. The final new copies of this release were made available for sale via Coil's Threshold House website on 1st February 2008. The line-up for the recorded show was also given on the Coil site, but does not appear on the release itself. Jhonn Balance does not appear on this recording. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Not On Label none Coil Porto (CD, Ltd, P/Unofficial) none Portugal 2006 (Coil) Porto (Box, Dlx, P/Unofficial, none Coil Not On Label none Portugal Unknown CD+) Not On Label none Coil Porto (CD, Ltd, P/Unofficial) none Portugal 2006 (Coil) Not On Label none Coil Porto (CD, Ltd, P/Unofficial, Pur) none Portugal 2006 (Coil) Not On Label none Coil Porto (CD, P/Unofficial, Ltd, 7th) none Portugal 2014 (Coil) Related Music albums to Porto by Coil 1. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Unpopular Culture and Explore Its Critical Possibilities and Ramifications from a Large Variety of Perspectives

15 mm front 153 mm 8 mm 19,9 mm 8 mm front 153 mm 15 mm 15 mm TELEVISUAL CULTURE TELEVISUAL CULTURE This collection includes eighteen essays that introduce the concept of Lüthe and Pöhlmann (eds) unpopular culture and explore its critical possibilities and ramifications from a large variety of perspectives. Proposing a third term that operates beyond the dichotomy of high culture and mass culture and yet offers a fresh approach to both, these essays address a multitude of different topics that can all be classified as unpopular culture. From David Foster Wallace and Ernest Hemingway to Zane Grey, from Christian rock and country to clack cetal, from Steven Seagal to Genesis (Breyer) P-Orridge, from K-pop to The Real Housewives, from natural disasters to 9/11, from thesis hatements to professional sports, these essays find the unpopular across media and genres, and they analyze the politics and the aesthetics of an unpopular culture (and the unpopular in culture) that has not been duly recognized as such by the theories and methods of cultural studies. Martin Lüthe is an associate professor in North American Cultural Studies at the John F. Kennedy-Institute at Freie Universität Berlin. Unpopular Culture Sascha Pöhlmann is an associate professor in American Literary History at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich. 240 mm Martin Lüthe and Sascha Pöhlmann (eds) Unpopular Culture ISBN: 978-90-8964-966-9 AUP.nl 9 789089 649669 15 mm Unpopular Culture Televisual Culture The ‘televisual’ names a media culture generally in which television’s multiple dimensions have shaped and continue to alter the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture.