The Development of Panoramic Sensibilities in Art, Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

Arm Und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in – Zur Ressourcenverteilung Arm Und Reich 2016 14/II

VORGESCHICHTE HALLE LANDESMUSEUMS FÜR DES TAGUNGEN in prähistorischen Gesellschaften in prähistorischen – Zur Ressourcenverteilung Arm und Reich Arm und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften Rich and Poor – Competing for resources in prehistoric societies 8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2o15 in Halle (Saale) Herausgeber Harald Meller, Hans Peter Hahn, Reinhard Jung und Roberto Risch 14/II 14/II 2016 TAGUNGEN DES LANDESMUSEUMS FÜR VORGESCHICHTE HALLE Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle Band 14/II | 2016 Arm und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften Rich and Poor – Competing for resources in prehistoric societies 8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2o15 in Halle (Saale) 8th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany October 22–24, 2o15 in Halle (Saale) Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle Band 14/II | 2016 Arm und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften Rich and Poor – Competing for resources in prehistoric societies 8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2o15 in Halle (Saale) 8th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany October 22–24, 2o15 in Halle (Saale) Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt landesmuseum für vorgeschichte herausgegeben von Harald Meller, Hans Peter Hahn, Reinhard Jung und Roberto Risch Halle (Saale) 2o16 Die Beiträge dieses Bandes wurden einem Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen. Die Gutachtertätigkeit übernahmen folgende Fachkollegen: Prof. Dr. Eszter Bánffy, Prof. Dr. Jan Bemmann, PD Dr. Felix Biermann, Prof. Dr. Christoph Brumann, Prof. Dr. Robert Chap- man, Dr. Jens-Arne Dickmann, Dr. Michal Ernée, Prof. Dr. Andreas Furtwängler, Prof. Dr. Hans Peter Hahn, Prof. Dr. Svend Hansen, Prof. Dr. Barbara Horejs, PD Dr. Reinhard Jung, Dr. -

Villas and Agriculture in Republican Italy

CHAPTER 20 Villas and Agriculture in Republican Italy Jeffrey A. Becker 1 Introduction The iconicity of the “Roman villa” affords it a rare status in that its appeal easily cuts across the boundaries of multiple disciplines. This is perhaps because the villa has always stimulated our imagination about the ancient world and cultivated a longing for that realm of convivial, pastoral bliss that the villa conjures up for us. Just as Seneca contem- plated Roman virtues in the context of the villa of Scipio Africanus (Sen. Ep. 86), mod- ern (and post-modern) thinkers continue to privilege the villa both as place and space, often using its realm as one in which to generate reconstructions and visions of the ancient past. In the nineteenth century the Roman villa appealed to the Romantics and the exploration of Vesuvian sites, in particular, fueled a growing scholarly interest in the architecture and aesthetics of the Roman villa (most recently, Mattusch, 2008). Often guided by ancient texts, villas were divided into typological groups, as were the interior appointments from wall paintings to floor mosaics. Villas seemed to be a homogeneous type, representative of a “Roman” cultural norm. The fascination with villa life began in antiquity, not only with the likes of Seneca but also poets and scholars such as Virgil and Varro. In spite of the iconic status of the villa from antiquity to modernity, a good deal of uncertainty remains with respect to the archaeology of Roman villas of the latter half of the first millennium. The scholarly approach to the Roman villa finds itself at something of a crossroads, particularly with respect to the villas of the Republican period in Italy. -

Locus Bonus : the Relationship of the Roman Villa to Its Environment in the Vicinity of Rome

LOCUS BONUS THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE ROMAN VILLA TO ITS ENVIRONMENT IN THE VICINITY OF ROME EEVA-MARIA VIITANEN ACADEMIC DISSERTATION TO BE PUBLICLY DISCUSSED, BY DUE PERMISSION OF THE FACULTY OF ARTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI IN AUDITORIUM XV, ON THE 2ND OF OCTOBER, 2010 AT 10 O’CLOCK HELSINKI 2010 © Eeva-Maria Viitanen ISBN 978-952-92-7923-4 (nid.) ISBN 978-952-10-6450-0 (PDF) PDF version available at: http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/ Helsinki University Print Helsinki, 2010 Cover: photo by Eeva-Maria Viitanen, illustration Jaana Mellanen CONTENTS ABSTRACT iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v LIST OF FIGURES, TABLES AND PLATES vii 1 STUDYING THE ROMAN VILLA AND ITS ENVIRONMENT 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.2 DEFINING THE VILLA 3 1.3 THE ROMAN VILLA IN CLASSICAL STUDIES 6 Origin and Development of the Villa 6 Villa Typologies 8 Role of the Villa in the Historical Studies 10 1.4 THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS 11 2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIAL AND WRITTEN SOURCES 15 2.1 RESEARCH HISTORY OF THE ROMAN CAMPAGNA 15 2.2 FIELDWORK METHODOLOGY 18 Excavation 18 Survey 19 2.3 ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIAL 21 Settlement Sites from Surveys and Excavations 21 The Sites Reclassified 25 Chronological Considerations 28 2.4 WRITTEN SOURCES 33 Ancient Literature 33 Inscriptions 35 2.5 CONCLUSIONS 37 3 GEOLOGY AND ROMAN VILLAS 38 3.1 BACKGROUND 38 3.2 GEOLOGY OF THE ROMAN CAMPAGNA 40 3.3 THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE OF THE ROMAN CAMPAGNA 42 3.4 WRITTEN SOURCES FOR THE USE OF GEOLOGICAL RESOURCES 44 3.5 ARCHAEOLOGY OF BUILDING MATERIALS 47 3.6 INTEGRATING THE EVIDENCE 50 Avoiding -

ROMANO- BRITISH Villa A

Prehistoric (Stone Age to Iron Age) Corn-Dryer Although the Roman villa had a great impact on the banks The excavated heated room, or of the River Tees, archaeologists found that there had been caldarium (left). activity in the area for thousands of years prior to the Quarry The caldarium was the bath Roman arrival. Seven pots and a bronze punch, or chisel, tell house. Although this building us that people were living and working here at least 4000 was small, it was well built. It years ago. was probably constructed Farm during the early phases of the villa complex. Ingleby Roman For Romans, bath houses were social places where people The Romano-British villa at Quarry Farm has been preserved in could meet. Barwick an area of open space, in the heart of the new Ingleby Barwick housing development. Excavations took place in 2003-04, carried out by Archaeological Services Durham University Outbuildings (ASDU), to record the villa area. This included structures, such as the heated room (shown above right), aisled building (shown below right), and eld enclosures. Caldarium Anglo-Saxon (Heated Room) Winged With the collapse of the Roman Empire, Roman inuence Preserved Area Corridor began to slowly disappear from Britain, but activity at the Structure Villa Complex villa site continued. A substantial amount of pottery has been discovered, as have re-pits which may have been used for cooking, and two possible sunken oored buildings, indicating that people still lived and worked here. Field Enclosures Medieval – Post Medieval Aisled Building Drove Way A scatter of medieval pottery, ridge and furrow earthworks (Villa boundary) Circular Building and early eld boundaries are all that could be found relating to medieval settlement and agriculture. -

Work at the Ancient Roman Villa: Representations of the Self, the Patron, and Productivity Outside of the City

Wesleyan University The Honors College Work at the Ancient Roman Villa: Representations of the Self, the Patron, and Productivity Outside of the City by Emma Graham Class of 2019 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors from the College of Letters and with Departmental Honors in Classical Civilizations Middletown, Connecticut April, 2019 TABLE&OF&CONTENTS! ! Acknowledgements! 2! ! Introduction! 3! Villa%Rustica%versus%Villa%Maritima%% 10% % % % % % % 2% Chapter!One:!Horace! 15! Remains!of!Horace’s!Villa% 18% Satire%2.6!on!Horace’s!Villa% 25% Chapter!Two:!Statius! 38! Silvae%1.3!on!the!Villa!of!Vopiscus%% 43% Silvae%2.2!on!the!Villa!of!Pollius!Felix%% 63% Chapter!Three:!Pliny!the!Younger! 80! Remains!of!Pliny!the!Younger’s!Tuscan!Villa%% 84% Epistula%5.6!on!Pliny!the!Younger’s!Tuscan!Villa%% 89% Epistula%9.36!on!Pliny!the!Younger’s!Tuscan!Villa% 105% Pliny!the!Younger’s!Laurentine!Villa% 110% Epistula%1.9!on!Pliny!the!Younger’s!Laurentine!Villa%% 112% Epistula%2.17!on!Pliny!the!Younger’s!Laurentine!Villa% 115% Conclusion!! 130! ! Appendix:!Images! 135! Bibliography!! 150! ! ! ! ! 1! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS!! ! To!the!places!I!have!worked.!Third!floor!of!Olin!Library!next!to!the!window,!with! a!strong!diagonal!light!from!the!left!always!illuminating!my!desK.!The!College!of! Letters!library,!with!free!coffee!that!sustained!me!and!endless!laughter!of!friends! that!are!so!dear!to!me.!My!room!on!Home!Ave.,!at!my!desk!under!the!large!poster! -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

Women Slaves and the Bacchic Murals in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii

Women Slaves and the Bacchic Murals in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii Elaine K. Gazda, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor The Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii has held a special place in the scholarly and popular imagination ever since the excavations of 1909-10 that uncovered the room containing the now famous murals of women performing rituals in the presence of the god Bacchus and members of his mythical entourage. These powerful images have given rise to numerous speculations, all of them highlighting the perspective of the elite members of the household and their social peers. Scholarly studies have proposed various interpretations—cultic, nuptial, mythological and prophetic, social, and theatrical. They also focus on the principal figures: the so-called “Domina,” “Bride” and other figures thought to represent the “Initiate.” In contrast, this paper considers meanings that the murals may have held for non-elite viewers—in particular, the female slaves and freed slaves of the household. It proposes that those household slaves identified with the women on the walls through the lens of their own experiences as slaves in both domestic and cultic contexts. Focusing on those women who play various supporting roles in the visual drama depicted on the walls, this paper contends that a number of “jobs” portrayed in the murals in cultic form correspond to jobs that female slaves of the household performed in their daily lives in the villa. Merely recognizing the work that the non-elite women on the walls perform would have allowed slaves and former slaves as viewers to identify with their depicted counterparts. -

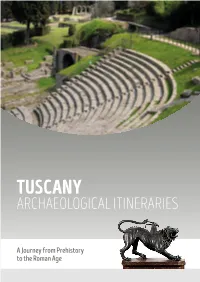

Get App Archaeological Itineraries In

TUSCANY ARCHAEOLOGICAL ITINERARIES A Journey from Prehistory to the Roman Age ONCE UPON A TIME... That’s how fables start, once upon a time there was – what? A region bathed by the sea, with long beaches the colour of gold, rocky cliffs plunging into crystalline waters and many islands dotting the horizon. There was once a region cov- ered by rolling hills, where the sun lavished all the colours of the earth, where olive trees and grapevines still grow, ancient as the history of man, and where fortified towns and cities seem open-air museums. There was once a region with ver- dant plains watered by rivers and streams, surrounded by high mountains, monasteries, and forests stretching as far as the eye could see. There was, in a word, Tuscany, a region that has always been synonymous with beauty and nature, art and history, especially Medieval and Renaissance history, a land whose fame has spread the world over. And yet, if we stop to look closely, this region offers us many more treasures and new histories, the emotion aroused only by beauty. Because along with the most famous places, monuments and museums, we can glimpse a Tuscany that is even more ancient and just as wonderful, bear- ing witness not only to Roman and Etruscan times but even to prehistoric ages. Although this evidence is not as well known as the treasures that has always been famous, it is just as exciting to discover. This travel diary, ad- dressed to all lovers of Tuscany eager to explore its more hidden aspects, aims to bring us back in time to discover these jewels. -

11 Amazing Day Trips You Can Take from Naples

22 JANUARY 2018 NEEN 3535 11 AMAZING DAY TRIPS YOU CAN TAKE FROM NAPLES One of the greatest benefits of visiting Naples is its close access to many nearby beaches, cathedrals, museums, and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Italy’s central coastline offers stunning natural scenery which continues to draw millions of tourists from around the world who come to eat, drink, and be merry under the silhouette of Naples historic past. Whether you’ve come to Naples to taste the region’s famous pizza, explore the elongated coastline, enjoy a cultural performance, or learn more about Italy’s rich heritage—there’s never a dull moment in your adventure with Ciao Florence. Embrace the spirit of “dolce vita” or the “sweet life” as our expert guides take you on a perfectly curated journey around the region of Campania. Florence based Tour Operator offers 11 different day trips from Naples to choose from, allowing you to tailor your Italian experience to satisfy your wanderlust. Indulge in the beautiful tranquility of the Italian countryside as we travel by bus, train, and even boat to cities like Pompeii, Capri, Sorrento, and the Amalfi Coast. Along the way you will be given lots of time to explore these cities for a more intimate connection to this historic Italian landscape. Whichever route you choose, feel confident that you are getting the most out of your Italian experience when you travel with Ciao Florence. From Naples to Pompeii Visit the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Pompeii which was made infamous in the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D.