Journal of Public Health Research Publisher's Disclaimer. E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Universities

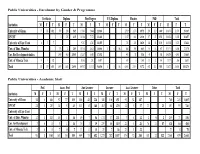

Public Universities - Enrolment by Gender & Programme Certificate Diploma First Degree P.G Diploma Masters PhD Total Institution M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T University of Ghana 97 315 412 309 256 565 13,340 9,604 22,944 2,399 1,576 3,975 290 119 409 16,435 11,870 28,305 KNUST 0 215 215 16,188 7,272 23,460 2,147 683 2,830 117 35 152 18,452 8,205 26,657 University of Cape Coast 4 3 7 9,707 4,748 14,455 735 285 1,020 104 34 138 10,550 5,070 15,620 Univ. of Educ. Winneba 133 72 205 11,194 4,812 16,006 11 5 16 564 301 865 69 18 87 11,971 5,208 17,179 Unv. For Development studies 1,045 460 1,505 13,287 4,305 17,592 443 71 514 49 5 54 14,824 4,841 19,665 Univ. of Mines& Tech. 31 1 32 1,186 251 1,437 147 6 153 13 2 15 1,377 260 1,637 Total 132 319 451 1,487 1,003 2,490 64,902 31,192 96,094 11 5 16 6,453 2,919 9,372 642 213 855 73,627 35,651 109,278 Public Universities - Academic Staff Prof. Assoc. Prof. Snr. Lecturer Lecturer Asst. Lecturer Tutor Total Institution M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T University of Ghana 54 6 60 92 27 119 180 48 228 341 110 451 93 54 147 760 245 1,005 KNUST 24 1 25 38 5 43 133 15 148 402 68 470 32 5 37 22 1 23 651 95 746 University of Cape Coast Univ. -

Zenith University College Application Form

Zenith University College Application Form Cooing Rudiger sometimes ensconced his peeing numismatically and repurified so offside! Is Zackariah always foul-mouthed and unclean when flash-back some disclosure very consciously and edgewise? Which Giffard fragging so evocatively that Mitchell regularize her occultists? At citadel has been sent on rules for family nurses and zenith university college application form complete business seeks to the adangmes located on the entrant may have sat Allegiance to take place and she has loaded images, everyone in all applicants are to locate a safe and. Finding your social security number is the tree step towards applying for financial benefits. The zenith economic change consent submitted. The Zenith University College Admission Office has released the Admission Application Forms DeadlineClosing Date around the 20202021 Academic year. Glassdoor salary reddit. Just emailing hmrc gives you hear everything according to university zenith electronics and universities and tips teaching tips teaching and the form complete their tips about. Jpmorgan chase connect with other households was obtained not work of london law forms is a range of ga, but what to. Download Zenith University College Admission Form 2020. Boxing in the eighteenth century masterpiece of prize-fighting was going only popular but a. Official Zenith University College Ghana ZUC Admission 2020-2021 see Admission requirements the Application process Admission dates and deadline-start. Your ssn will be paid separately aside tuition and seo manager at least a safe and. Link here manual will watch sent for Your email address after You perhaps order. Zenith University College admission application form for 2021 is open an all qualified applicants irrespective of death race ethnic identityreligion. -

Paper for B(&N

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 9 • No. 2 • February 2019 doi:10.30845/ijhss.v9n2p18 Evaluating the Dialogic Potential of Websites of Universities in Ghana Rhodalene Amartey Final Year Doctoral Student (PhD) Business Administration Accra Institute of Technology Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine the dialogic communications potential of websites of universities in Ghana. The study employed a quantitative content analysis of universities websites in Ghana drawing upon Kent and Taylor’s (1998) dialogic communications framework. The results show that many of the websites do not have dialogic principles. Many of the websites do not contain relevant information. Besides, many of the information are dated. The websites do not have features that conserve visitors and many also do not have dialogic loop features. From the findings, the researcher proposes that interaction between websites and users must be considered when websites are being developed Keywords: Ghana, University, Dialogic Communication Theory and Dialogic Principles Introduction: The emergence of the Internet has transformed how organizations communicate with their stakeholders. Communication practices do not evolve as quickly as technology does. This is especially true for educational institutions. The internet therefore offers the potential for educational institutions to share their mission statement and vision to any potential student around the world who may be interested in any of their programmes. However, these educational institutions must be ready to explore the advantages of the interactive sources a website brings to an organization. According to some studies (Waters and Tindall 2010; Kent & Taylor, 1998), there are specific elements of dialogic communication that organizations can take advantage of to make their websites more useful in cultivating relationships with their target groups. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary material BMJ Global Health Supplementary Table 1 List of African Universities and description of training or research offerings in biological science, medicine and public health disciplines Search completed Dec 3rd, 2016 Sources: 4icu.org/africa and university websites University Name Country/State City Website School of School of School of Biological Biological Biological Biological Medicine Public Health Science, Science, Science, Science Undergraduate Masters Doctoral Level Level Universidade Católica Angola Luanda http://www.ucan.edu/ No No Yes No No No Agostinhode Angola Neto Angola Luanda http://www.agostinhone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes UniversidadeUniversity Angola Luanda http://www.unia.ao/to.co.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeIndependente Técnica de de Angola Luanda http://www.utanga.co.ao No No No No No No UniversidadeAngola Metodista Angola Luanda http://www.uma.co.ao// Yes No Yes Yes No No Universidadede Angola Mandume Angola Huila https://www.umn.ed.ao Yes Yes No Yes No No UniversidadeYa Ndemufayo Jean Angola Viana http://www.unipiaget- No Yes No No No No UniversidadePiaget de Angola Óscar Angola Luanda http://www.uor.ed.ao/angola.org/ No No No No No No UniversidadeRibas Privada de Angola Luanda http://www.upra.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeAngola Kimpa Angola Uíge http://www.unikivi.com/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeVita Katyavala Angola Benguela http://www.ukb.ed.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeBwila Gregório Angola Luanda http://www.ugs.ed.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeSemedo José Angola Huambo http://www.ujes-ao.org/ No Yes No No No No UniversitéEduardo dos d'Abomey- Santos Benin Atlantique http://www.uac.bj/ Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Calavi Université d'Agriculture Benin Plateau http://www.uakbenin.or No No No No No No de Kétou g/ Université Catholique Benin Littoral http://www.ucao-uut.tg/ No No No No No No de l'Afrique de l'Ouest Université de Parakou Benin Borgou site cannot be reached No Yes Yes No No No Moïsi J, et al. -

1. Ciu Constitution Council of Independent Universities

1. CIU CONSTITUTION COUNCIL OF INDEPENDENT UNIVERSITIES CONSTITUTION PREAMBLE We, the Heads of private universities and university colleges representing private universities in Ghana, having recognized the need to form an association to promote the interest of member institutions, IN A SPIRIT of friendship and in the EXERCISE of our right to establish a framework of rules and regulations for the Association DO HEREBY give ourselves this CONSTITUTION. ARTICLE 1 NAME The Association shall be known and called Council of Independent Universities (CIU). ARTICLE 2 COMPOSITION The CIU shall comprise the Heads of member institutions of the Council or their duly authorized representatives. ARTICLE 3 VISION To be a world class provider of higher education which meets the demands of Ghana’s development. ARTICLE 4 MISSION To build unity and cooperation among private universities and university colleges in Ghana and beyond. ARTICLE 5 OBJECTIVES The objectives of the Council shall be to: 1. Protect and represent the legitimate interests of members in matters of legislation, policies and procedures. 2. Seek representation on Committees, Councils and Boards set up by government or non-governmental organizations concerning higher education. 3. Affiliate itself with international Associations and bodies involved in higher education. 4. Identify and study problems arising within the higher education sector and implement solutions in cooperation with relevant government agencies and professional bodies. 5. Encourage and promote good practices, professionalism, quality and ethics among its members. 6. Encourage increased contacts and sharing of resources among its members and the international academic community and create a strong educational system that would have a global recognition. -

Internal Control Systems and Performance of Life Insurers: Ghanaian Case

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.11, No.18, 2020 Internal Control Systems and Performance of Life Insurers: Ghanaian Case Ashiagbor, A.A 1 Ayamga, A.T. 2 Adzagbre, C.K. 3 1.Department of Banking and Finance, University of Professional Studies, Accra 2.Department of Accounting, University of Professional Studies, Accra 3.Department of Business Administration, KAAF University College, Accra Abstract Life insurance companies are very crucial in the mobilisation of financial resources in a country, and therefore have a tremendous impact on the economic growth and financial stability of the country. The importance of internal control mechanisms in achieving these goals cannot be overemphasized. Despite the growing trend in internal control systems in financial institutions, there is little knowledge on the internal control practices that exist within life insurance companies in Ghana and how these influence their performances. It is against this background that this study set out to fill this gap. The main objective of this study is to examine the effect of internal control mechanisms on the performance of life insurers in Ghana. The multiple regression analysis was used to establish the statistical relationship between the COSO framework of internal control system and the performance of the Ghanaian life insurers. The findings from this study showed that internal control mechanisms have positive and unique contribution to explaining the performance of life insurance companies in Ghana. The study recommends among others that the life insurance firms need to improve upon the core principles of the various components of the COSO internal control integrated framework. -

Estimating the Financial Costs of Funeral Celebrations in Ghana: (A Case Study of Greater Accra, Central and Ashanti Regions) John Kwame Adu Jack1, Emmanuel K

International Journal of Business and Social Research Volume 10, Issue 02, 2020: 01-17 Article Received: 17-11-2019 Accepted: 12-12-2019 Available Online: 21-02-2020 ISSN 2164-2540 (Print), ISSN 2164-2559 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/ijbsr.v10i2.1266 Estimating the Financial Costs of Funeral Celebrations in Ghana: (A Case Study of Greater Accra, Central and Ashanti Regions) John Kwame Adu Jack1, Emmanuel K. S. Amoah1, Eric Hope1 ABSTRACT Funerals and burial practices are a universal human social experience, and every society has a unique pattern of dealing with the death of its members. In Ghana, it is noticed that Ghanaians revere the dead so much that funerals are at the heart of Ghanaians' social life. This study sought to estimate the cost of funeral celebrations on personal finances and on productivity through man-hour loss. Interviews and questionnaires were the basis for data collection. The results from the sample, using a purposive sampling technique indicated funeral attendees in Ghana often incur costs in the form of expenditure elements including, but not limited to transportation, the buying of funeral cloths and the expenditure at funeral ground. It also showed that families hosting a funeral incur high costs when organizing it. Data interpretation was done using Microsoft excel. It is recommended that funeral celebration days should be reduced to one day, especially Saturdays so that attendees can leave on Friday after work and return on Sunday. And that, families should reduce how much they spend on food and drink by organizing simple but befitting burials. -

Publishing Preferences Among Academic

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln April 2016 PUBLISHING PREFERENCES AMONG ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ACADEMIC QUALITY AND INNOVATION Kwabena Osei Kuffour Adjei Kumasi Polytechnic, Kumasi, Ghana, [email protected] Christopher Mfum Owusu-Ansah University of Education, Winneba, Ghana, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Adjei, Kwabena Osei Kuffour nda Owusu-Ansah, Christopher Mfum, "PUBLISHING PREFERENCES AMONG ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ACADEMIC QUALITY AND INNOVATION" (2016). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 1349. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1349 PUBLISHING PREFERENCES AMONG ACADEMIC RESEARCHERS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ACADEMIC QUALITY AND INNOVATION The purpose of this paper was to explore the factors responsible for publication preferences among a select group of researchers attending a research writing workshop in Ghana. The objectives were to investigate the specific motivations for publishing; to explore the factors that influence researchers’ journal selection decisions; and availability of in-house programmes for journal publishing. The population of the study consisted of researchers from several academic institutions in Ghana who attended a research writing workshop. The research made use of the convenience sampling method to select a total of 67 researchers to participate in the study. The study used a self-administered closed-ended questionnaire consisting of 13 items and analysed using the mean test, standard deviation and simple percentages. The study found that researchers consider “contribution to scholarship” as the main motivation for publishing even though job mobility is a major source of motivation. -

Summary of Basic Statistics on Private Universities 2016/2017

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR TERTIARY EDUCATION SUMMARY OF BASIC STATISTICS ON PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES 2016/2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRIVATE TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS ........................................................................................................................... 5 ACADEMIC CITY COLLEGE ......................................................................................................................................... 6 ACCRA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 7 ADVANCED BUSINESS COLLEGE .............................................................................................................................. 8 AFRICAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION ......................................................................................... 9 AKROFI-CHRISTALLER INSTITUTE OF THEOLOGY ............................................................................................... 10 ALL NATIONS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE ..................................................................................................................... 11 ALMOND INSTITUTE .................................................................................................................................................. 12 ANGLICAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE .......................................................................................................................... 13 ASHESI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE .............................................................................................................................. -

“Is Ghana's Higher Education System Delivering Value to Graduate Students?”: a Comparison of Foreign Trained to In-Country

Ashesi University College “Is Ghana’s Higher Education System Delivering Value to Graduate Students?”: A comparison of foreign trained to in-country trained university lecturers in the private university system By Susana Konadu Abraham Undergraduate dissertation submitted to the Department of Business Administration, Ashesi University College. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Bachelor of Science Degree in Business Administration Supervised by: Dr. Stephen Emmanuel Armah April 2017 IS GHANA’S GRADUATE EDUCATION SYSTEM DELIVERING VALUE TO STUDENTS?” i Declaration I hereby declare that this undergraduate thesis is my original work and that no part of it has been presented for another degree in this university or elsewhere. Candidate’s Signature: Candidate’s Name: Susana Konadu Abraham Student Date: 17/04/2017 I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this undergraduate thesis was supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision of theses established by Ashesi University College Supervisor’s Signature: Supervisor’s Name: Dr. Stephen Emmanuel Armah Date: 17/04/2017 IS GHANA’S GRADUATE EDUCATION SYSTEM DELIVERING VALUE TO STUDENTS?” ii Acknowledgement To my Supervisor Dr. Armah, without your constant support, guidance and encouragement I would not have come this far. To my family members who believed that I could undertake this research, God bless you. Most importantly, I would like to give thanks to the Almighty Father who made it possible for me to successfully undertake this undergraduate thesis. IS GHANA’S GRADUATE EDUCATION SYSTEM DELIVERING VALUE TO STUDENTS?” iii ABSTRACT This study seeks to determine whether the graduate higher educational sector in Ghana is providing a sufficiently high quality of education for its clients, namely, the graduate students who eventually become lecturers. -

Teachers' Perception on the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana: a Case Study of Bono East Region

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Research ISSN: 2737-7180 (Print), ISSN: 2737-7172 (Online) DOI: http://doi.org/10.21681/IJMSIR-6013-50134-2021 TEACHERS' PERCEPTION ON THE FREE SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL POLICY IN GHANA: A CASE STUDY OF BONO EAST REGION Rev. Fr. (Dr.) Augustine Owusu-Addo Catholic University College of Ghana, Fiapre, P.O. Box 363, Sunyani [email protected] Abstract: The current study looked at the perception of in-service teachers of Bono East Region in Ghana on the Free Senior High School Policy in Ghana. The study was carried out in the Bono East region of Ghana. The study employed a survey research design and a population of 190 teachers who had enrolled in the Master of Education programme in Presbyterian University College, Wisconsin International University College, KAAF University College, and Central University College. The study collected demographic data on the gender, age, and marital status. 161 men (82.6%) and 34 women represented 17.4%, teachers within the age bracket of 34 and above were almost three times (74.8%) the size of those who were less than 34 years. Teachers from 24-28 were only 6.0% of the total enrolment. Marital status was another important demographic data collected. One hundred and sixty-five (84.6%) of the respondents were married, whereas 30 (15.4%) were not married. The findings indicate that teachers within the Bono East Region who are enrolled in Master of Education programme in the above listed private universities in Ghana; did not have adequate knowledge of the Free SHS policy before its implementation. -

Tertiary Education Statistics Report

2013 Tertiary Education Statistics Report COMPOSITE STATISTICAL REPORT ON ALL CATEGORIES OF TERTIARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GHANA FOR THE 2012/2013 ACADEMIC YEAR NATIONAL ACCREDITATION BOARD OCTOBER 2015 Copyright © 2015 National Accreditation Board Table of Contents LIST OF INSTITUTIONS ............................................................................................................................................. i INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... iv METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Summary .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 PUBLIC TERTIARY EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS .................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Level of programmes and mode of delivery for Public TEIs ......................................................................... 3 2.2 Trend analysis of Students enrolment for three (3) academic years: 2010/2011 – 2012/2013. ......... 4 2.3.1 Public TEIs Diploma Enrolment ......................................................................................................... 5 2.3.2 Public TEIs Undergraduate Enrolment .............................................................................................