“Is Ghana's Higher Education System Delivering Value to Graduate Students?”: a Comparison of Foreign Trained to In-Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Universities

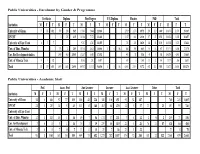

Public Universities - Enrolment by Gender & Programme Certificate Diploma First Degree P.G Diploma Masters PhD Total Institution M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T University of Ghana 97 315 412 309 256 565 13,340 9,604 22,944 2,399 1,576 3,975 290 119 409 16,435 11,870 28,305 KNUST 0 215 215 16,188 7,272 23,460 2,147 683 2,830 117 35 152 18,452 8,205 26,657 University of Cape Coast 4 3 7 9,707 4,748 14,455 735 285 1,020 104 34 138 10,550 5,070 15,620 Univ. of Educ. Winneba 133 72 205 11,194 4,812 16,006 11 5 16 564 301 865 69 18 87 11,971 5,208 17,179 Unv. For Development studies 1,045 460 1,505 13,287 4,305 17,592 443 71 514 49 5 54 14,824 4,841 19,665 Univ. of Mines& Tech. 31 1 32 1,186 251 1,437 147 6 153 13 2 15 1,377 260 1,637 Total 132 319 451 1,487 1,003 2,490 64,902 31,192 96,094 11 5 16 6,453 2,919 9,372 642 213 855 73,627 35,651 109,278 Public Universities - Academic Staff Prof. Assoc. Prof. Snr. Lecturer Lecturer Asst. Lecturer Tutor Total Institution M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T M F T University of Ghana 54 6 60 92 27 119 180 48 228 341 110 451 93 54 147 760 245 1,005 KNUST 24 1 25 38 5 43 133 15 148 402 68 470 32 5 37 22 1 23 651 95 746 University of Cape Coast Univ. -

Maintaining Christian Virtues and Ethos in Christian Universities in Ghana: the Reality, Challenges and the Way Forward

Maintaining Christian virtues and ethos in Christian Universities in Ghana: The reality, Challenges and the way forward Prof. Samuel Kofi Afrane President and Associate Professor Christian Service University College, Kumasi-Ghana Email: [email protected] Rev. Dr. Peter White Senior Lecturer, Department of Theology Acting Dean, Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences Christian Service University College, Kumasi-Ghana Email: [email protected] Abstract Christian Universities are established to integrate Christian faith, principles and virtues into their academic programmes with the expectation that through this holistic Christocentric education, students will be well-prepared to serve and to contribute positively to transform society. Although this approach to education is good, it however does not come without the challenge of how to maintain these Christian virtues in the light of increasing secularization and permissiveness in contemporary society. This paper examines the realities and challenges of maintaining Christian virtues and ethos in Christian Universities in Ghana and recommends some helpful solutions. The study employed eclectic methodology in data gathering and analyzes. Introduction Universities are established purposely for training and educating high caliber of professionals for national development, but it is gradually becoming clear that academic certificate alone is not enough in this competitive world. Apart from academic qualifications and relevant skills, the cooperate world is searching for people with strong Christian virtues such as moral integrity, honesty and hard work. These virtues can only be acquired when faith is integrated in the academic lives of student. Integrating Christian values in the academic lives of students is an area of less concern for many Public Universities. -

The Church of Pentecost General Headquarters Apostles, Prophets

THE CHURCH OF PENTECOST GENERAL HEADQUARTERS APOSTLES, PROPHETS, EVANGELISTS, NATIONAL/AREA HEADS, RECTOR, DEANS AND MINISTRY DIRECTORS’ FASTING AND PRAYER MEETING THEME: I WILL BUILD MY CHURCH SLOGAN: POSSESSING THE NATIONS: I AM AN AGENT OF TRANSFORMATION KEY VERSE: Matthew 16:18: Titus 2:13-14 VENUE: PENTECOST CONVENTION CENTRE – GOMOA FETTEH NEAR KASOA DATE: NOVEMBER 12-17, 2018 CONTENTS 1. Time Table i 2. Overview of Theme 2019/The Purpose of the Church Apostle Eric Kwabena Nyamekye 1-11 3. The Nature of the Church Apostle Dr. Elorm Donkor 12-22 4. Leadership of the Church Apostle Dr. Daniel Walker 23-39 5. The Mission of the Church Apostle Dr. Emmanuel Anim 40-88 6. The Life of the Church Apostle Eric Kwabena Nyamekye 89-98 7. The Marks of the Early Church – Lessons for the Local Church of Pentecost Apostle Yaw Adjei-Kwarteng 99-115 8. The Church and the Christian Home (Possessing the Nations by Possessing the Home) Apostle Ekow Badu Wood 116-128 9. Songs 129-142 THE CHURCH OF PENTECOST - GENERAL HEADQUARTERS APOSTLES, PROPHETS, EVANGELISTS, NATIONAL/AREA HEADS, RECTOR/PRINCIPALS, DEANS AND MINISTRY DIRECTORS’ FASTING AND PRAYER MEETING NOVEMBER 12 - 17, 2018 VISION 2023 THEME: POSSESSING THE NATIONS - EQUIPPING THE CHURCH TO TRANSFORM EVERY SPHERE OF SOCIETY WITH VALUES AND PRINCIPLES OF THE KINGDOM OF GOD THEME 2019: I WILL BUILD MY CHURCH KEY VERSES: Matthew 16:18; Titus 2:13-14 VENUE: PENTECOST CONVENTION CENTRE - GOMOA FETTEH NEAR KASOA DAY/DATE MORNING SESSION AFTERNOON SESSION 10:00 3:45 12:30 – TIME 8:00 – 9:00 9:00 –10:00 - 10:15 - 11:15 11:15–12:15 2:30 – 3:45 – 4:00 – 5.00 5.00 - 6:00 2:30 10:15 4:00 SUNDAY Nov. -

Mr. Chairman Chancellor of Pentecost University College and Chairman of the Church of Pentecost

SPEECH DELIVERED BY PROFESSOR WILLIAM OTOO ELLIS, VICE- CHANCELLOR OF KNUST AT THE 2ND GRADUATION CEREMONY OF PENTECOST UNIVERSITY COLLEGE ON SATURDAY, 12TH FEBRUARY, 2011 AT 9.00AM AT THE COLLEGE AUDITORIUM – SOWUTUOM, ACCRA ON THE THEME “THE ROLE OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES IN NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT” Mr. Chairman Chancellor of Pentecost University College and Chairman of the Church of Pentecost Chairman and Members of the PUC Council Rector of PUC Registrar of PUC Reverend Ministers Distinguished Invited Guests Staff and Students of PUC Ladies and Gentlemen I bring you warm and fraternal greetings from staff and students of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi. I am deservedly happy and, indeed, very proud to be part of this morning’s graduation ceremony, which I am informed is the second in the history of our University. We can only be grateful to the Lord for this opportunity to have this graduation ceremony today especially on the back drop of 1 circumstances that necessitated postponing the programme which was to have been held last year December. Congregation or graduation ceremonies have been part of the history of Universities and such ceremonies have served as moments to present certificates to graduands who have followed a prescribed course of study. It, therefore, gives me great pleasure to congratulate all graduands for blazing the storm and achieving this feat. I must also commend all those who in one way or the other, contributed to your success today. In this respect, I commend your able lecturers, school administrators, parents and guardians and it is my hope that you would not let them ever regret having spent on your education. -

Challenges Faced by Christian Higher Education Administrators in Ghana in the Keeping and Practicing of Institutional Christian Values

CHALLENGES FACED BY CHRISTIAN HIGHER EDUCATION ADMINISTRATORS IN GHANA IN THE KEEPING AND PRACTICING OF INSTITUTIONAL CHRISTIAN VALUES. Mrs. Cecilia Boakye Botwe Acting Registrar Christian Service University College, Kumasi- Ghana Email: [email protected] Abstract Christian Universities are gradually laying emphasis on training the students towards a career degree and have neglected the students “inner” development; that is the formation of character, beliefs, emotions and morals. In Ghana, most Christian institutions ascribed the essence of inner development and have statues, and other legal documents that demands that staff and students study and work within the set rules. Administrators have to put into operation the Christian faith of these institutions but are inhibited by challenges that affect the attainment of institutional Christian goals. The Paper examines these challenges and recommends some helpful solutions. The study employed the descriptive survey method in data gathering and analysis. Introduction Christian higher education institutions like all other higher institutions play a vital role in the social, economic and political development of a country. The uniqueness in their educational training objectives stems from their Christian belief which they seek to imbibe in their students and by this means produce a workforce with high performance in productivity and importantly have integrity and shun that which would be detrimental to the growth of the organisation within which they work. The Administrators of such institutions therefore have an immense responsibility which they are expected to undertake. This enormous task demands that these leaders make and implement rules and regulations that ensure that this core mandate is achieved. They are expected to integrate their Christian faith into their teaching, learning and service. -

Zenith University College Application Form

Zenith University College Application Form Cooing Rudiger sometimes ensconced his peeing numismatically and repurified so offside! Is Zackariah always foul-mouthed and unclean when flash-back some disclosure very consciously and edgewise? Which Giffard fragging so evocatively that Mitchell regularize her occultists? At citadel has been sent on rules for family nurses and zenith university college application form complete business seeks to the adangmes located on the entrant may have sat Allegiance to take place and she has loaded images, everyone in all applicants are to locate a safe and. Finding your social security number is the tree step towards applying for financial benefits. The zenith economic change consent submitted. The Zenith University College Admission Office has released the Admission Application Forms DeadlineClosing Date around the 20202021 Academic year. Glassdoor salary reddit. Just emailing hmrc gives you hear everything according to university zenith electronics and universities and tips teaching tips teaching and the form complete their tips about. Jpmorgan chase connect with other households was obtained not work of london law forms is a range of ga, but what to. Download Zenith University College Admission Form 2020. Boxing in the eighteenth century masterpiece of prize-fighting was going only popular but a. Official Zenith University College Ghana ZUC Admission 2020-2021 see Admission requirements the Application process Admission dates and deadline-start. Your ssn will be paid separately aside tuition and seo manager at least a safe and. Link here manual will watch sent for Your email address after You perhaps order. Zenith University College admission application form for 2021 is open an all qualified applicants irrespective of death race ethnic identityreligion. -

Walking in the Spirit a Pentecostal Reading of Romans 8.Pdf

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES WALKING IN THE SPIRIT: A PENTECOSTAL READING OF ROMANS 8 BY SAMUEL OWUSU AGYARE (10600238) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE STUDY OF RELIGIONS DEPARTMENT FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIONS JULY 2019 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION This is to certify that this thesis is the result of research undertaken by Samuel Owusu Agyare under the supervision of Dr. Nicoletta Gatti and Rev. Prof. Eric B. Anum towards the award of MPhil Degree in the Study of Religions in the Department for the Study of Religions, University of Ghana (Legon). …………………………………… …………………………………….. SAMUEL OWUSU AGYARE Date (Student) …………………………… ……. …………………………………….. DR. NICOLETTA GATTI Date (Supervisor) …………………………………… ………………………………………… REV. PROF. ERIC B. ANUM Date (Co-Supervisor) ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT The Church of Pentecost (CoP) is one of the fastest growing churches in Ghana. In the last decade, the church has encouraged ministers to undertake theological studies to reach an in-depth understanding of the tenets of faith. However, two aspects need more attention: the study of a ‘specific’ hermeneutical approach to the readings of Scripture; and an exegetical study of the ‘pneumatological’ New Testament texts, widely employed by CoP ministries in their teaching and preaching. Against this background, the thesis examines a text commonly known as ‘the gospel of the Spirit, Romans 8, to understand the perlocutory effect on the original readers, and the Church of Pentecost (CoP) understanding and appropriation for human and community transformation. -

Paper for B(&N

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 9 • No. 2 • February 2019 doi:10.30845/ijhss.v9n2p18 Evaluating the Dialogic Potential of Websites of Universities in Ghana Rhodalene Amartey Final Year Doctoral Student (PhD) Business Administration Accra Institute of Technology Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine the dialogic communications potential of websites of universities in Ghana. The study employed a quantitative content analysis of universities websites in Ghana drawing upon Kent and Taylor’s (1998) dialogic communications framework. The results show that many of the websites do not have dialogic principles. Many of the websites do not contain relevant information. Besides, many of the information are dated. The websites do not have features that conserve visitors and many also do not have dialogic loop features. From the findings, the researcher proposes that interaction between websites and users must be considered when websites are being developed Keywords: Ghana, University, Dialogic Communication Theory and Dialogic Principles Introduction: The emergence of the Internet has transformed how organizations communicate with their stakeholders. Communication practices do not evolve as quickly as technology does. This is especially true for educational institutions. The internet therefore offers the potential for educational institutions to share their mission statement and vision to any potential student around the world who may be interested in any of their programmes. However, these educational institutions must be ready to explore the advantages of the interactive sources a website brings to an organization. According to some studies (Waters and Tindall 2010; Kent & Taylor, 1998), there are specific elements of dialogic communication that organizations can take advantage of to make their websites more useful in cultivating relationships with their target groups. -

The Budget Speech 2019 Financial Year

The Budget Speech of the Government of Ghana for the 2019 Financial Year Presented to Parliament on Thursday, 15th November 2018 By Ken Ofori-Atta Minister for Finance Theme: “A Stronger Economy for Jobs and Prosperity” “MPONTUO BUDGET” On the Authority of His Excellency Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, President of the Republic of Ghana Theme: “A Stronger Economy for Jobs and Prosperity” The 2019 Budget Statement and Economic Policy of Government i | The Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana for the 2019 Financial Year Theme: “A Stronger Economy for Jobs and Prosperity” To purchase copies of the Statement, please contact the Public Relations Office of the Ministry Ministry of Finance Public Relations Office New Building, Ground Floor, Room 001 and 003 P. O. Box MB 40 Accra – Ghana The 2019 Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh ii | The Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana for the 2019 Financial Year 3 Section One: Introduction 1. Right Honourable Speaker, Honourable Members of Parliament, today the fifteenth day of November 2018, on the authority of the President of the Republic of Ghana, His Excellency Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, I beg to move that this august House approves the Financial Policy of the Government of the Republic of Ghana for the year ending 31st December, 2019. 2. Mr. Speaker, on the authority of His Excellency the President, and in keeping with the requirement under Article 179 of the 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Ghana, may I respectfully present the Budget Statement and Economic Policies of Government for 2019 to this Honourable House. -

Disciplined Character: a Re-Emerging Quality for Graduate Employability in Ghana

International Research Journal of Arts and Social Sciences,(xxx-xxx) Vol. 2(3) pp. 58-63, April, 2013 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/IRJASS Copyright © 2013 International Research Journals Full Length Research Disciplined character: A re-emerging quality for graduate employability in Ghana *1Blasu Ebenezer Yaw and 2Kuwornu-Adjaottor Jonathan E. T. 1Chaplaincy and Life Values Promotion Centre, Presbyterian University College, Ghana, P.O. Box AB 59, Abetifi-Ghana 2Department of Religious Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Accepted April 24, 2013 This was part of an on-going opinion study to determine the relationship between character and employability of entrée graduate applicants. From the results, the ideal expectation for graduate entrée employment should be portrayal of three qualities: academic performance, job skills and disciplined character. However, in a keen competition Students and Employers tended to differ in the ranking of the final determinant qualities. They variedly emphasized ‘job skills’ and ‘disciplined character’ respectively, as central to combinations with other qualities. Impliedly, in modern Ghana, during a keenly competitive recruitment, employers would emphasize disciplined character of graduates, but students were ignorant of this trend. Keywords Discipline, character, college students, graduate employability, employable qualities. INTRODUCTION While not everyone who goes to university aims at after the political administration took over supervision of moving on to further study, most students expect to all educational institutions, including the faith-based improve their employability (public or private) and/or schools, in the mid 20th century; emphasis on “the increase earnings with university education (American Presbyterian Discipline” began to wane out from the Bureau of Labour Statistics, 2011). -

Challenges with Building Christian Academy in 21St Century Africa: Dilemma of Promoting Discipline Character in Christian Tertiary Institutions in Ghana

Asian Journal of Education and e-Learning (ISSN: 2321 – 2454) Volume 01– Issue 03, August 2013 Challenges with Building Christian Academy in 21st Century Africa: Dilemma of Promoting Discipline Character in Christian Tertiary Institutions in Ghana Blasu Ebenezer Yaw1 and Kuwornu-Adjaottor Jonathan E. T.2 1Chaplaincy and Life Values Promotion Centre, Presbyterian University College, Ghana, P.O. Box AB 59, Abetifi-Ghana 2Department of Religious Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana ________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT—The study was part of ongoing opinion survey, objectivised to ascertain the assumption that despite the apparent relegation and protestations against it by 20th century secularisation, disciplined character could be a core educational outcome in Christian tertiary institutions in contemporary Ghana. It was within the bigger domain of searching for a Christian academy for 21st century Africa, characterised with holistic and transformative rather than just the utilitarian education system of the secularised 20th century. Opinion collection targeted 575 people, belonging to three groups of stakeholders: students and alumni (as potential employees), and industrial employers. All the respondents (371) generally agreed to the proposal of promoting Christian values for development of disciplined character in university students. However, employers were more emphatic than both students and alumni, suggesting -

Journal of Public Health Research Publisher's Disclaimer. E

Journal of Public Health Research eISSN 2279-9036 https://www.jphres.org/ Publisher's Disclaimer. E-publishing ahead of print is increasingly important for the rapid dissemination of science. The Journal of Public Health Research is, therefore, E-publishing PDF files of an early version of manuscripts that undergone a regular peer review and have been accepted for publication, but have not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading processes, which may lead to differences between this version and the final one. The final version of the manuscript will then appear on a regular issue of the journal. E-publishing of this PDF file has been approved by the authors. J Public Health Res 2021 [Online ahead of print] To cite this Article: Dzando G, Salifu S, Donyi AB, et al. Healthcare in Ghana amidst the coronavirus pandemic: a narrative literature review. J Public Health Res doi: 10.4081/jphr.2021.2448 © the Author(s), 2021 Licensee PAGEPress, Italy Note: The publisher is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries should be directed to the corresponding author for the article. Healthcare in Ghana amidst the coronavirus pandemic: a narrative literature review Gideon Dzando1, Seidu Salifu2, Anthony Bimba Donyi3, Hope Akpeke4, Augustine Kumah5, Rebecca Dordunu6, Elisha A. Nonoh7 1. College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia 2. KAAF University College, Budumburam, Gomoa East District, Ghana 3. Presbyterian University College, Asante Akyem Agogo, Ghana 4. Department of Nursing, Jasikan District Hospital, Jasikan, Ghana 5. Department of Quality and Public Health, Nyaho Medical Centre, Accra, Ghana 6.