Once Upon a Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

John Haskell Kemble Maritime, Travel, and Transportation Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8v98fs3 No online items John Haskell Kemble Maritime, Travel, and Transportation Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Charla DelaCuadra. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Prints and Ephemera 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © March 2019 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. John Haskell Kemble Maritime, priJHK 1 Travel, and Transportation Collection: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: John Haskell Kemble maritime, travel, and transportation collection Dates (inclusive): approximately 1748-approximately 1990 Bulk dates: 1900-1960 Collection Number: priJHK Collector: Kemble, John Haskell, 1912-1990. Extent: 1,375 flat oversized printed items, 162 boxes, 13 albums, 7 oversized folders (approximately 123 linear feet) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection forms part of the John Haskell Kemble maritime collection compiled by American maritime historian John Haskell Kemble (1912-1990). The collection contains prints, ephemera, maps, charts, calendars, objects, and photographs related to maritime and land-based travel, often from Kemble's own travels. Language: English. Access Series I is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. Series II-V are NOT AVAILABLE. They are closed and unavailable for paging until processed. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

SS City of Paris

SS City of Paris SS Belgenland SS Arizona SS Servia SS City of Rome Launched 1865 e Inman Line Launched 1878 e Red Star Line Launched 1879 e Guion Line Launched 1881 e Cunard Line Launched 1882 e Anchor Line For most of its life, The SS Servia the SS City of Paris This ship spent The ships of the was the first large The SS City of Rome was a passenger most of her life Guion Line were ocean liner to be was built to be the with the Red Star known mostly as United Kingdom largest and fastest United Kingdom ship. At her fastest, United Kingdom U.S. & Belgium United Kingdom built of steel in- she could make it Line working as a immigrant ships. stead of iron, and the first Cunard ship of her time, but the builders from Queenstown, Ireland to New passenger ship between Antwerp At the time of her launch, the SS Line ship with any electric lighting. used iron instead of steel for her hull, York City in 9 days. In 1884, she was and New York City. She was sold Arizona was one of the fastest ships At the time of its launch, her public making her too heavy for fast speeds. sold to the American Fur Company to the American Line in 1895 and on the Atlantic, but took so much rooms were the most luxurious of However, her First Class quarters and converted to a cargo ship. The worked for 8 more years as a 3rd coal and was so uncomfortable that any ocean-going ship. -

JESSE ATHERSYCH (Aka JAMES ATHERSUCH)

JESSE ATHERSYCH (a.k.a. JAMES ATHERSUCH), 1873 – 1930 James Athersuch was born in Foleshill near Coventry in 1873 and was christened Jesse Athersych, son of James Potter Athersych and Elizabeth (nee Palmer). James Potter Athersych had like generations before him started work as a Loom Weaver but later had become a Policeman in Rugby where he is reputed to have been responsible for the last man ever to be put in stocks! By the time Jesse was born his father was a labourer but by 1881 was railway crossing keeper at Bedlam Crossing in Coventry where he remained until his death in 1905. James was a religious man and joined the Folehill Independent Chapel in 1869 where he was at one time involved with the running of the Sunday school. On 2 nd April 1866 he married Elizabeth Palmer, a cotton winder, at St Lawrence Foleshill. Jesse had an elder sister, Emma Jane (b.1867) and brother, Fred (b. 1870), and two younger sisters Sarah Elizabeth (b.1879) and Margaret Annie (b. 1880). The family at first lived in Bacon’s Fields in Foleshill but had moved to Tinsley’s Lane by 1881, and by 1891 to 1 Field View, Foleshill. By 1891 Jesse was working as a fitter in a cycle factory possibly at the same factory as his brother Fred. Mass production of bicycles had only just begun and Coventry was for a time the centre of manufacture. What Jesse did between 1891 and 1900 is not known for sure but there is a family story which my father told me that he “ran away to sea” when he was young and returned with riches which he poured onto the kitchen table. -

Rare Books and Special Collections Cruises Travel Literature

Rare Books and Special Collections Cruises Travel Literature Collection Accession Number: SC 17:40 Location: RB-M Dates: 1872-1990 Size: 1 record cartons; 1.0 cu. ft. Creator/Collector: Collected by SLPL staff Acquisition info: Collected by SLPL staff Accruals: No accruals expected Custodial history: Collection assembled by SLPL staff (various branches) and stored in Central Library in former “Tin Room.” At some point was moved to storage room at Compton Branch Library. Moved from Compton Branch Library storage to Rare Books and Manuscripts in September 2017. Language: Primarily English but also includes German, French, Italian, Japanese, and Swedish , Processed by: Amanda Bahr-Evola, January 2018 Conservation notes: Items placed into acid free envelopes and into acid free record cartons. Metal fasteners removed. Scope and Content: Collection of travel literature related to cruises and steamships spanning the globe. Much of the collection dates from the 1930s- 1940s. Brochures and publications from travel companies and transportation companies are featured. Arrangement: Collection organized alphabetically by company name Restrictions: No restrictions Remarks: “st” indicates the year that was stamped on the item by SLPL September 2017 Rare Books and Special Collections Series: RB-M SC 17: 05 Cruises Travel Literature Collection 1 record carton; 1.0 cu. ft. Box/Folder Description 1/1 Finding aide 1/- General “What to Know About Ocean Travel” International Mercantile Marine Company “Passenger Ships Owned by the United States Government” United States Shipping board Emergency Fleet Corporation American Express Travel Department “West Indies Cruises” (1920) “Crowded Season Sailings to & from Europe” (1931) “Steamship Sailings & Travel Guide” (1927, 1928) “Niagara to the Saguenay—a cruise down the St. -

Shelf List 12/12/2013 Matches 6753

Shelf List 12/12/2013 Matches 6753 Author Title Call# Subject Home Location The Fighting and Sinking of the USS Johnston VA65.J64 1991 BATTLE OFF SAMAR: YAMATO, NAGATO, Lending Library Shelves (DD-557) - Battle Off Samar As Told by her crew KONGO, HURUNA, CHOKAI, KLUMANO, SUZUYA, CHIJUMA, TONE, YAHAGI, NOSHIRO U.S.S. San Diego - Mediterranean Cruise 1982 - VA65.S6 1989 Lending Library Shelves 1983 Glimpses of Australia - Souvenir for the US Navy DU104.G6 1908 United States. Navy --Cruise, 1907-1909. [from old Loan Library Stacks catalog] Australia --Pictorial works. The Bluejackets' Manual US Navy 1927 V113.B55 1927 Loan Library Stacks The Bluejackets' Manual 1943 V113.B55 1943 Loan Library Stacks Helicopter Capital - U.S. Naval Auxiliary Air VG94.R4 1956 Lending Library Shelves Station, Ream Field, Imperial Beach, Ca Bikini Scientific Resurvey, Jul - Sep 1947 QE75 1947 CRUISE Library Research Room (non-lending materials) Fighter Squadron 54 - Korean Cruise 1952-53 VA65.F54 1953 AIR GROUP Lending Library Shelves U.S.S. Alfred A. Cunningham Dd 752 Korean VA65.C752 CRUISE BOOK USS ALFRED A . CUNNINGHAM Cruise Book Shelves Cruise 1951 1951 DD 752 1954 - 1955 Cruise Log of the USS Arnold J. VA65.I869 1955 CRUISE BOOK USS ARNOLD J. ISBELL DD 869 Cruise Book Shelves Isbell Dd 869 U.S.S. Brown DD 546 Wake of the Brown Jun 52 VA65.B546 CRUISE BOOK USS BROWN Cruise Book Shelves - Jan 53 1953 U.S.S. Cleveland Cl 55 - WW II VA65.C55 1946 CRUISE BOOK USS CLEVELAND Cruise Book Shelves U.S.S. Columbia Cl 56: Battle Record and VA65.C56 1945 CRUISE BOOK USS COLUMBIA Lending Library Shelves History 1942 - 45 U.S.S. -

Red Star Line Cruises

RED STAR LINE CRUISES INHOUD INLEIDING (Philip Heylen) 8 CRUISES EN DE RED STAR LINE 14 Het toevluchtsoord. De cruiseschepen van de Red Star Line (Bram Beelaert) 16 ‘Selling a boatride’. Hoe de Red Star Line toeristenreizen 36 en cruises in de markt zette (Marie-Charlotte Le Bailly) De crew op cruise. Een blik achter de schermen van 54 het drijvende hotel Belgenland (Marie-Charlotte Le Bailly) ‘Bring back a new self!’ Vrouwen aan boord van 72 de Red Star Line-cruises (An Lombaerts) CRUISES EN DE WERELD 88 Het interbellum. Een wereld van contrasten (1919-1939) (Gerrit Verhoeven) 90 Een wereld van bestemmingen. Een wereld van reizen (Mike Robinson) 102 Hawaï. Promotie voor het paradijs (DeSoto Brown) 114 Reizen naar Egypte van de negentiende eeuw tot de Tweede Wereldoorlog. 124 Thomas Cook, het moderne reizen en de opkomst van het Amerikaanse tijdperk (Waleed Hazbun) CRUISES EN TOERISME 134 Homo Touristicus. Een geschiedenis met zevenmijlslaarzen (Gerrit Verhoeven) 136 Gepamperd in een gouden kooi op de Middellandse Zee (Ayfer Erkul) 148 Notenapparaat 160 Chronologisch overzicht van Red Star Line-cruises 168 Bibliografie 172 Over de auteurs 175 INLEIDING ★ Philip Heylen Schepen voor Cultuur, Economie, Stads- en Buurtonderhoud, Patrimonium en Erediensten, Stad Antwerpen Beste lezer, interventies en thematische presentaties leggen ze de link tussen het historische kernverhaal en de bredere thematiek van mense- Voor u ligt het tweede boek van het Red Star Line Museum bij lijke migratie. Trouw aan de formule van het museum, vertrekt Davidsfonds Uitgeverij. Het eerste verscheen in het najaar van ‘Cruise Away. Met de Red Star Line de wereld rond’ van de ge- 2013, toen het nieuwe museum zijn deuren opende in Antwer- schiedenis van de Red Star Line als cruisemaatschappij en de pen, op de plek in de oude haven waar ooit ongeveer twee miljoen ervaringen van de cruisereizigers, om het publiek te laten reflec- landverhuizers de boot naar Amerika namen. -

Travel & Exploration Cruise Ship Memorabilia – Cartography

Sale 449 Thursday, March 10, 2011 1:00 PM Rare Americana – Travel & Exploration Cruise Ship Memorabilia – Cartography Auction Preview Tuesday, March 8, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wedesnsday, March 9, 9:00 am to 3:00 pm Thursday, March 10, 9:00 am to 1:00 pm Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

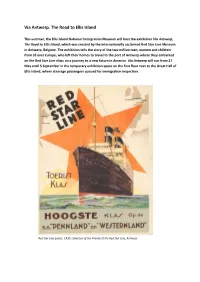

Via Antwerp. the Road to Ellis Island

Via Antwerp. The Road to Ellis Island This summer, the Ellis Island National Immigration Museum will host the exhibition Via Antwerp, The Road to Ellis Island, which was created by the internationally acclaimed Red Star Line Museum in Antwerp, Belgium. The exhibition tells the story of the two million men, women and children from all over Europe, who left their homes to travel to the port of Antwerp where they embarked on the Red Star Line ships on a journey to a new future in America. Via Antwerp will run from 27 May until 5 September in the temporary exhibition space on the first floor next to the Great Hall of Ellis Island, where steerage passengers queued for immigration inspection. Red Star Line poster, 1930, collection of the Friends of the Red Star Line, Antwerp 1. About the exhibition – Via Antwerp. The Road to Ellis Island From 1815 until 1940, around 60 million emigrants from all over Europe left their homeland for America in hopes of a better life. From 1873 to 1934, the Red Star Line shipping company ferried nearly two million of these emigrants from Antwerp in Belgium to the United States. Most of them arrived in New York. In this tiny yet compelling exhibition, the Red Star Line Museum brings their story back to the U.S., and Ellis Island in particular. The narrative elaborates on a typical journey to New York around 1900 and starts in a travel agency of the Red Star Line in Russia. Migrants would then illegally cross the border from Russia into the West, travelling by train to Antwerp, where they would walk through the city and to the port and board a Red Star Line ship for the long ocean voyage before arriving at Ellis Island.