Jean Nouvel 2008 Laureate Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________August 12, 2008 I, _________________________________________________________,Heather Farrell-Lipp hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture in: The School of Architecture and Interior Design It is entitled: Strategies between old and new: adaptive use of an industrial building This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Michael McInturf _______________________________Jeffery Tilman _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Strategies between Old and New: Adaptive Use of an Industrial Building A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture In the School of Architecture and Interior Design August 12 2008 By Heather Farrell-Lipp Thesis committee: Michael McInturf, Jeffery Tilman Abstract ▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄ In the complex, fast-paced environment of this country, we have often disposed of building stock that could have been potentially adapted to meet our changing needs leaving environments with no connection to the past or local identity. This haphazard way of approaching our environment takes no advantage of our ability as sentient beings to truly engage in eloquent, sustainable combinations of the old and new. Through engaging the question of what we truly value in this country and how that can be defined through architectural quality, we look at a series of case studies that have successfully expressed a combination between the old and the new. This thesis defines some guiding principles inherent in successful resolutions. It does not give specified stylistic requirements but rather suggests that the old be fully understood, respected and engaged as part of a final combination with a clear hierarchy culminating in a unified expression. -

“HERE/AFTER: Structures in Time” Authors: Paul Clemence & Robert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Book : “HERE/AFTER: Structures in Time” Authors: Paul Clemence & Robert Landon Featuring Projects by Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry, Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe, and Many Others, All Photographed As Never Before. A Groundbreaking New book of Architectural Photographs and Original Essays Takes Readers on a Fascinating Journey Through Time In a visually striking new book Here/After: Structures in Time, award-winning photographer Paul Clemence and author Robert Landon take the reader on a remarkable tour of the hidden fourth dimension of architecture: Time. "Paul Clemence’s photography and Robert Landon’s essays remind us of the essential relationship between architecture, photography and time," writes celebrated architect, critic and former MoMA curator Terence Riley in the book's introduction. The 38 photographs in this book grow out of Clemence's restless search for new architectural encounters, which have taken him from Rio de Janeiro to New York, from Barcelona to Cologne. In the process he has created highly original images of some of the world's most celebrated buildings, from Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum to Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao. Other architects featured in the book include Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, I.M. Pei, Studio Glavovic, Zaha Hadid and Jean Nouvel. However, Clemence's camera also discovers hidden beauty in unexpected places—an anonymous back alley, a construction site, even a graveyard. The buildings themselves may be still, but his images are dynamic and alive— dancing in time. Inspired by Clemence's photos, Landon's highly personal and poetic essays take the reader on a similar journey. -

Introducing Tokyo Page 10 Panorama Views

Introducing Tokyo page 10 Panorama views: Tokyo from above 10 A Wonderful Catastrophe Ulf Meyer 34 The Informational World City Botond Bognar 42 Bunkyo-ku page 50 001 Saint Mary's Cathedral Kenzo Tange 002 Memorial Park for the Tokyo War Dead Takefumi Aida 003 Century Tower Norman Foster 004 Tokyo Dome Nikken Sekkei/Takenaka Corporation 005 Headquarters Building of the University of Tokyo Kenzo Tange 006 Technica House Takenaka Corporation 007 Tokyo Dome Hotel Kenzo Tange Chiyoda-ku page 56 008 DN Tower 21 Kevin Roche/John Dinkebo 009 Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka Kenzo Tange 010 Metro Tour/Edoken Office Building Atsushi Kitagawara 011 Athénée Français Takamasa Yoshizaka 012 National Theatre Hiroyuki Iwamoto 013 Imperial Theatre Yoshiro Taniguchi/Mitsubishi Architectural Office 014 National Showa Memorial Museum/Showa-kan Kiyonori Kikutake 015 Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance Company Building Kunio Maekawa 016 Wacoal Building Kisho Kurokawa 017 Pacific Century Place Nikken Sekkei 018 National Museum for Modern Art Yoshiro Taniguchi 019 National Diet Library and Annex Kunio Maekawa 020 Mizuho Corporate Bank Building Togo Murano 021 AKS Building Takenaka Corporation 022 Nippon Budokan Mamoru Yamada 023 Nikken Sekkei Tokyo Building Nikken Sekkei 024 Koizumi Building Peter Eisenman/Kojiro Kitayama 025 Supreme Court Shinichi Okada 026 Iidabashi Subway Station Makoto Sei Watanabe 027 Mizuho Bank Head Office Building Yoshinobu Ashihara 028 Tokyo Sankei Building Takenaka Corporation 029 Palace Side Building Nikken Sekkei 030 Nissei Theatre and Administration Building for the Nihon Seimei-Insurance Co. Murano & Mori 031 55 Building, Hosei University Hiroshi Oe 032 Kasumigaseki Building Yamashita Sekkei 033 Mitsui Marine and Fire Insurance Building Nikken Sekkei 034 Tajima Building Michael Graves Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1010431374 Chuo-ku page 74 035 Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki Store Jun Aoki 036 Gucci Ginza James Carpenter 037 Daigaku Megane Building Atsushi Kitagawara 038 Yaesu Bookshop Kajima Design 039 The Japan P.E.N. -

Frei Otto 2015 Laureate Media Kit

Frei Otto 2015 Laureate Media Kit For more information, please visit pritzkerprize.com. © 2015 The Hyatt Foundation Contents Contact Media Release ................................ 2 Tributes to Frei Otto ............................ 4 Edward Lifson Jury Citation .................................. 9 Director of Communications Jury Members .................................10 Pritzker Architecture Prize Biography ....................................11 [email protected] Past Laureates .................................14 +1 312 919 1312 About the Medal ...............................17 History of the Prize .............................18 Evolution of the Jury. .19 Ceremonies Through the Years ................... 20 2015 Pritzker Architecture Prize Media Kit Media Release Announcing the 2015 Laureate Frei Otto Receives the 2015 Pritzker Architecture Prize Visionary architect, 89, dies in his native Germany on March 9, 2015 Otto was an architect, visionary, utopian, ecologist, pioneer of lightweight materials, protector of natural resources and a generous collaborator with architects, engineers, and biologists, among others. Chicago, IL (March 23, 2015) — Frei Otto has received the 2015 Pritzker Architecture Prize, Tom Pritzker announced today. Mr. Pritzker is Chairman and President of The Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the prize. Mr. Pritzker said: “Our jury was clear that, in their view, Frei Otto’s career is a model for generations of architects and his influence will continue to be felt. The news of his passing is very sad, unprecedented in the history of the prize. We are grateful that the jury awarded him the prize while he was alive. Fortunately, after the jury decision, representatives of the prize traveled to Mr. Otto’s home and were able to meet with Mr. Otto to share the news with him. At this year’s Pritzker Prize award ceremony in Miami on May 15 we will celebrate his life and timeless work.” Mr. -

New York — 24 September 2019

ÁLVARO SIZA Curated by Guta Moura Guedes New York — 24 September 2019 PRESS KIT A Bench For a Tower The First Stone programme is offering a bench made of Portuguese Estremoz marble, designed by Álvaro Siza, for his Tower in New York. The presentation of the bench is on the 24th of September at the sales gallery of the building in Manhattan and includes a presentation by the architect. After several projects developed and presented in Venice, Milan, Weil am Rhein, São Paulo, London, Lisbon and New York, the First Stone programme returns to this iconic North-American city - this time to present Hell’s Kitchen Bench, designed by the Pritzker Prize winning architect Álvaro Siza, specifically for the lobby of his new tower on the island of Manhattan. Hell’s Kitchen Bench is a large-scale streamlined bench, created for one of the most striking new residential projects in New York city: 611 West 56th Street, the first building by Álavro Siza, one of the greatest architects of our time, on American soil. This bench, also designed by the Architect, was commissioned within the scope of the First Stone programme, which has become a cornerstone for the promotion of Portuguese stone and its industry throughout the world. The bench is a gift from the First Stone programme and will be permanently installed within the lobby of this skyscraper. Its presentation to the press and a select group of guests will occur in New York on Tuesday the 24th of September around 4:30 pm, and will include the participation of Álvaro Siza. -

Lecture Handouts, 2013

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #1 INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW Introductions Expectations Textbooks Assignments Electronic reserves Research Project Sources History-Theory-Criticism Methods & questions of Architectural History Assignments: Initial Paper Topic form Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #2 ARCHITECTURE OF WWII The World at War (1939-45) Nazi War Machine - Rearming Germany after WWI Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect & responsible for Nazi armaments Autobahn & Volkswagen Air-raid Bunkers, the “Atlantic Wall”, “Sigfried Line”, by Fritz Todt, 1941ff Concentration Camps, Labor Camps, POW Camps Luftwaffe Industrial Research London Blitz, 1940-41 by Germany Bombing of Japan, 1944-45 by US Bombing of Germany, 1941-45 by Allies Europe after WWII: Reconstruction, Memory, the “Blank Slate” The American Scene: Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941 Pentagon, by Berman, DC, 1941-43 “German Village,” Utah, planned by US Army & Erich Mendelsohn Military production in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Akron, Cleveland, Gary, KC, etc. Albert Kahn, Detroit, “Producer of Production Lines” * Willow Run B-24 Bomber Plant (Ford; then Kaiser Autos, now GM), Ypsilanti, MI, 1941 Oak Ridge, TN, K-25 uranium enrichment factory; town by S.O.M., 1943 Midwest City, OK, near Midwest Airfield, laid out by Seward Mott, Fed. Housing Authortiy, 1942ff Wartime Housing by Vernon Demars, Louis Kahn, Oscar Stonorov, William Wurster, Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, Skidmore-Owings-Merrill, et al * Aluminum Terrace, Gropius, Natrona Heights, PA, 1941 Women’s role in the war production, “Rosie the Riverter” War time production transitions to peacetime: new materials, new design, new products Plywod Splint, Charles Eames, 1941 / Saran Wrap / Fiberglass, etc. -

Tech-3 Guthrie Katie Sara Ke.Pdf

A study on the Guthrie Theater Guthrie Theater | Jean Nouvel Technical Research Study Conducted by Katie Loechen, Ke Zhoa, and Sara Marquardt Arch 5565 | Fall 2014 BIOGRAPHY was created, JND has developed over 100 design objects and Atliers had designed over 200 projects. The main office is located in Paris, and is one of the largest architectural firms in France. Nouvel was born in France in 1948 after the war, and grew up in a mileu of structuralists. he inherited a love of learning and exploration from INFLUENCE | POSITION GLOBALLY his parents, both teachers. At an early age he wanted to be an artist, but his parents insisted he take a more practical path. There an interest in Nouvel has been a key participant in intellectual debates in France since the early part of his career. In 1976, Nouvel architecture was born, originally as a compromise. and Marin Robain cofounded the Mars 1976, a movement aimed at promoting the inhabitants’ participation to the conception of their living environment. Additionally, he founded the French labor union for architects in 1977, called Rendering of National Art Museum of China (2014) After a year of preparation, Nouvel failed the entry exam for the Syndicat de l’Architecture. architecture in Bordeaux. A year later, he retook the test for the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and came in first. His time at the École des Beaux- Nouvel’s first big break into the international architecture community did not come until 1987. In that year, the Arts proved to be a poor fit for Nouvel’s philosophy in architeccture. -

Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Commission

José Selgas & Lucía Cano There is no budget for the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion commission. It is paid for by sponsorship, sponsorship help-in-kind, and the sale of the finished structure, which does not cover more than 40% of its cost. The Serpentine Gallery collaborates with a range of companies and individuals whose support makes it possible to realise the Pavilion. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Commission The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion commission was conceived by Serpentine Gallery Director, Julia Peyton-Jones, in 2000. It is an ongoing programme of temporary structures by internationally acclaimed architects and designers. It is unique worldwide and presents the work of an international architect or design team who, at the time of the Serpentine Gallery's invitation, has not completed a building in England. Each Pavilion is sited on the Gallery’s lawn for three months and the immediacy of the process – a maximum of six months from invitation to completion – provides a peerless model for commissioning architecture. Park Nights, the Gallery’s acclaimed programme of public talks and events, will take place in Sejima and Nishizawa’s (SANAA’s) Pavilion, and will culminate in the annual Marathon event that takes place in October. In 2006 the Park Nights programme included the now legendary 24-hour Serpentine Gallery Interview Marathon, convened by Hans Ulrich Obrist and architect Rem Koolhaas, which was followed, in 2007, by the Serpentine Gallery Experiment Marathon presented by artist Olafur Eliasson and Obrist, which featured experiments performed by leading artists and scientists. In 2008, Obrist led over 60 participants in the Serpentine Gallery Manifesto Marathon. -

LIGHT CONSTRUCTION Fact Sheet

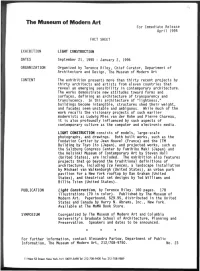

/o The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release April 1995 FACT SHEET EXHIBITION LIGHT CONSTRUCTION DATES September 21, 1995 - January 2, 1996 ORGANIZATION Organized by Terence Riley, Chief Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art CONTENT The exhibition presents more than thirty recent projects by thirty architects and artists from eleven countries that reveal an emerging sensibility in contemporary architecture. The works demonstrate new attitudes toward forms and surfaces, defining an architecture of transparency and translucency. In this architecture of "lightness," buildings become intangible, structures shed their weight, and facades seem unstable and ambiguous. While much of the work recalls the visionary projects of such earlier modernists as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Pierre Chareau, it is also profoundly influenced by such aspects of contemporary culture as the computer and electronic media. LIGHT CONSTRUCTION consists of models, large-scale photographs, and drawings. Both built works, such as the Fondation Cartier by Jean Nouvel (France) and the ITM Building by Toyo Ito (Japan), and projected works, such as the Salzburg Congress Center by Fumihiko Maki (Japan) and the Helsinki Museum of Contemporary Art by Steven Hoi 1 (United States), are included. The exhibition also features projects that go beyond the traditional definitions of architecture, including Ice Fences, a landscape installation by Michael van Walkenburgh (United States), an urban park pavilion for a New York rooftop by Dan Graham (United States), and theatrical set designs by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien (United States). PUBLICATION Light Construction, by Terence Riley. 160 pages. 178 illustrations (70 in color). -

CORB++ 6 Credits ARCH 456 Le Corbusier in Context 3 Cr

SUMMER 2015 MAY 18 – JUNE 26 CORB++ 6 credits ARCH 456 Le Corbusier in Context 3 cr. A Study of the architecture, painting, sculpture, applied arts and milieu of Corb ARCH 497 Reflective Recordings 3cr. A method of active observation and creative production Itinerary Map 4 countries 15 cities +/- Sites Le Corbusier Contemporary Architecture Architects UNStudio Group8 Shigeru Bahn Yi Architects Jean Tschumi Wiel Arets Architecture James Stirling and Partners Bernard Tschumi Phalt Architekten Spillman Delugan Meissel SANAA Eschle Architekten Mies van der Rohe Piano and Rogers Andrea Maffei Architects Hans Scharoun Jean Nouvel Cino Zucchi Archietti Santiago Calatrava Dominique Perrault Carta Associates Damien Karl Moser Lacaton and Vassal Fluchaire & Julien Cogne Gigon & Guyer Boerli Studio Holzer Kober Cormac David Chipperfield Institute for Lightweight Christophe Gulizzi Alsop Robert Maillart Structure Architects 2b_architectes Gustav Zeuner Institute for Computational Heinz Isler Matte Trucco Design Lacroix Chessex Renzo Piano Frei Otto Herzog and De Meuron Foster and Partners Jorg Schlaich Edouard Francois Eileen Gray Werner Sobek Manuelle Gautrand Rudy Rocciotti Hascher Jehle Architektur AS Architecture Studio Zaha Hadid GWJ Architektur Victor Laloux and Gae Kengo Kuma Otto and Werner Pfister Aulenti Museums of Modern and Contemporary Art Historic Buildings and Public Spaces Travel Expenses Estimated cost for the trip is $4200. This includes: Airfare 1200 Trains 560 Transit 105 Hotels 1300 Entries 215 Food 820 There is the potential for the cost to be less based on each students’ choice of flight and hotels. Costs are based on mid-priced hotels. Train fares are as of January, 2015 and may be less when booked. -

New EPO Site the Hague Press Dossier Imprint

New EPO Site The Hague Press dossier Imprint: Published and edited by: European Patent Office, Munich, Germany, © EPO 2018 Credits Photography (cover, page 4 , page 6 and page 9) Ronald Tilleman Illustrations on page 7 and 11 Ateliers Jean Nouvel – Dam & Partners Architecten – TBI Consortium New Main Introduction The European Patent Office (EPO) inaugurates its new premises in Rijswijk, near The Hague, in the presence of His Majesty King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands on 27 June 2018. Financed entirely from the Office’s own resources, the The decision to construct a new building was a result of a new premises are the EPO’s largest single investment in its firm resolution to provide EPO staff with a state-of-the-art 40-year history in the Netherlands. With a budget of some workplace – one that would be sustainable, symbolise the EUR 205 million, this new architectural landmark was designed EPO’s commitment to supporting innovation in Europe, and by renowned architects Ateliers Jean Nouvel of Paris and underline its close ties with the Netherlands, and The Hague Dam & Partners Architecten of Amsterdam – and Diederik region in particular. Dam describes it as the slimmest and tallest glass and steel construction of its kind in Europe. The new building will enable the EPO to utilise greater synergies between its operational units in Rijswijk by bringing The EPO has deep historical roots in Rijswijk, and today it them together on one site. EPO staff will start working in is one of the EPO’s most important sites both in terms of the new building from this autumn, and the old tower will staffing and operations. -

What Is Frank Gehry Doing About Labor Conditions in Abu Dhabi?

ARCHITECTURAL RECORD NOVEMBER 2014 news 21 D A ILY UPDAT ES archrecord.com/news twitter.com/archrecord perspective I can’t think of a profession better equipped for social change than architecture. —Ivenue Love-Stanley, cofounder of Atlanta-based architecture firm Stanley Love-Stanley, speaking at record’s first Women in What Is Frank Gehry Architecture Forum & Awards on October 10 in New York City. Doing About Labor Conditions in Abu Dhabi? BY ANNA FIXSEN Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District will include (above, from left) Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Jean Nouvel’s Louvre satellite, and Zaha Hadid’s Performing Arts Centre. since the guggenheim Museum announced Gehry may be the first prominent architect local government should take responsibility plans for its Frank Gehry–designed satellite in to take steps toward labor reform on Saadiyat for problems with labor conditions. (On August Abu Dhabi eight years ago, the project has Island, the luxury arts and real-estate 21, Hadid filed a lawsuit in New York County been part of debates and protests concerning development 500 meters off the shore of Abu Supreme Court against critic Martin Filler and the treatment of migrant construction workers Dhabi where the Guggenheim, after years of The New York Review of Books for errors in an and the role of architects in their safety and delays, is expected to soon begin construction. article about conditions on the site of her Al well-being. But, behind the scenes, Gehry has The museum will join Rafael Viñoly’s New Wakrah soccer stadium in Qatar, which had been working with a human-rights lawyer and York University Abu Dhabi (completed this yet to begin construction.) “I don’t have the the country’s state-run development authority year), Norman Foster’s Zayed National Museum power to make these changes,” Hadid told the to improve conditions for laborers on his site.