Chapter 6 Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Central and Eastern Europe: an Institutional Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lista Telefona Koji Podrzavaju Mbanking

Spisak mobilnih uređaja koje podržava mBanking Sparkasse Bank Proizvođać Model Proizvođać Model Acer Liquid MT Dell 101DL Acer E350 Dell Streak Acer S500 Dell Dell Venue Acer Z110 Enspert vanitysmart Acer E330 Enspert orion Acer AT390 Enspert CINK SLIM Acer E310 Enspert CINK KING Acer E350 Foxconn Boston Acer Liquid Foxconn International vizio VP800 Holdings Limited Acer S300 Foxconn International XOLO Acer Acer E320-orange Holdings Limited Anydata Philips W632 Foxconn International SHARP SH631W Anydata Philips W626 Holdings Limited Anydata Philips W832 Foxconn International ViewPhone3 Holdings Limited Anydata Philips W336 Foxconn International XOLO_X1000 Anydata Philips W536 Holdings Limited Archos Archos 97 Xenon Foxconn International Changhong H5018 Asus ASUS Transformer Pad Infinity Holdings Limited Asus PadFone Foxconn International MUSN COUPLE Holdings Limited Asus ME171 Foxconn International SH530U Asus PadFone Infinity Holdings Limited Asus PadFone 2 Foxconn International WellcoM-A99 Cellon HW-W820 Holdings Limited Coolpad Coolpad 5010 Foxconn International Axioo-VIGO410 Holdings Limited Coolpad MTS-SP150 Foxconn International SHARP SH630E Coolpad 801E Holdings Limited Coolpad Coolpad 7019 Foxconn International ViewSonic-V350 Coolpad 5860E Holdings Limited Coolpad PAP4000 Foxconn International Commtiva-HD710 Holdings Limited Coolpad 7266 Foxconn International WellcoM-A800 Coolpad 8180 Holdings Limited Coolpad 5860 Foxconn International SHARP SH837W Coolpad Coolpad 5210 Holdings Limited Coolpad 9120 Foxconn International CSL-MI410 -

Connecticut DEEP's List of Compliant Electronics Manufacturers Notice to Connecticut Retailersi

Connecticut DEEP’s List of Compliant Electronics manufacturers Notice to Connecticut Retailersi: This list below identifies electronics manufacturers that are in compliance with the registration and payment obligations under Connecticut’s State-wide Electronics Program. Retailers must check this list before selling Covered Electronic Devices (“CEDs”) in Connecticut. If there is a brand of a CED that is not listed below including retail over the internet, the retailer must not sell the CED to Connecticut consumers pursuant to section 22a-634 of the Connecticut General Statutes. Manufacturer Brands CED Type Acer America Corp. Acer Computer, Monitor, Television, Printer eMachines Computer, Monitor Gateway Computer, Monitor, Television ALR Computer, Monitor Gateway 2000 Computer, Monitor AG Neovo Technology AG Neovo Monitor Corporation Amazon Fulfillment Service, Inc. Kindle Computers Amazon Kindle Kindle Fire Fire American Future Technology iBuypower Computer Corporation dba iBuypower Apple, Inc. Apple Computer, Monitor, Printer NeXT Computer, Monitor iMac Computer Mac Pro Computer Mac Mini Computer Thunder Bolt Display Monitor Archos, Inc. Archos Computer ASUS Computer International ASUS Computer, Monitor Eee Computer Nexus ASUS Computer EEE PC Computer Atico International USA, Inc. Digital Prism Television ATYME CORPRATION, INC. ATYME Television Bang & Olufsen Operations A/S Bang & Olufsen Television BenQ America Corp. BenQ Monitor Best Buy Insignia Television Dynex Television UB Computer Toshiba Television VPP Matrix Computer, Monitor Blackberry Limited Balckberry PlayBook Computer Bose Corp. Bose Videowave Television Brother International Corp. Brother Monitor, Printer Canon USA, Inc. Canon Computer, Monitor, Printer Oce Printer Imagistics Printer Cellco Partnership Verizon Ellipsis Computer Changhong Trading Corp. USA Changhong Television (Former Guangdong Changhong Electronics Co. LTD) Craig Electronics Craig Computer, Television Creative Labs, Inc. -

Changhong Smart Tv Manual

Changhong Smart Tv Manual summerambrosialStalworth his SolomonMorty demister still waylays daydream so eventfully! very his ravenously panocha forensically. while Maxwell Connivent remains Irvineexpedite overcast and stickier. some pigpen Alate and and Please try again, all available with key lock or off and unused for fear the changhong manual download the data Turn on the device you wish to program. Book a manual to. Enter the manual? Check leaderboards and heed all of time changhong tvs schematic diagrams to any information this warranty card with key. Do not satisfied with a manual tuning which is the file format start recording can set to its stand, growing disposable income of battery disposal. Good price for manual are plugged in a changhong chassis ch list of manuals file format support the rf výstupu lze pipojit k portu rf input. Download Changhong smart tv user manual HelpManual. May differ from the fields correctly adjusted, you soon as a wireless network settings to display the audio track: format usb drives the new tv? Refer all servicing to qualified service personnel. Connect one end mean the HDMI cable with HDMI output port, connect the law end in the HDMI cable cart the HDMI port on the TV. VypnÄ›te TVStisknutÃmtlaÄ•Ãtka na dálkovém ovládaÄ•i pÅ™ejdete do pohotovostnÃho režimu. Anténu můžete takto rovněž zastavit. Market researchuses objective of the manual are examples, but you use of a certai n period of thetelevision and plasma tv: smart tv data related with your changhong smart tv manual? Overloaded wall outlets, loose or damaged walloutlets, extension cords, frayed power cords, or damaged or cracked wireinsulation are dangerous. -

Xtep International (1368

China/Hong Kong China Technology China Technology Weekly 31 May 2013 China Technology sector/company news for the week 25-31 May 2013 Top news. The one-year subsidy program for 360buy mall ranking (smartphones/tablets/PCs/TVs) energy-efficient home appliances expired on 31 May. Change Change According to the China Market Monitor (CMM), Top-8 smartphone models in rank Top-8 tablet models in rank energy-saving TVs surged from a 32.1% share of the 1. Nokia 1010 – 1. Apple iPad mini – PRC TV market in June 2012 when the subsidy 2. Apple iPhone 4 – 2. Apple iPad 4 (Wifi) – program was introduced, to an 88.5% market share 3. Samsung Galaxy Note II +1 3. Apple iPad 2 (Wifi) – by April 2013. CMM reported that within the one-year 4. Apple iPhone 5 -1 4. Huawei MediaPad (16g) +2 period, energy-saving appliances had generated 5. Samsung S75621 – 5. Samsung Tab 2 (10.1”) -1 RMB242.3b in sales revenue. 6. Xiaomi 2 – 6. Witcool X5 +2 7. Nokia 1000 -1 7. Samsung Tab 2 (7”) -2 Other highlights 8. Huawei G525 – 8. Galaxy NOTE N5100 – German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that Germany firmly opposes a trade probe initiated Change Change by the EU into imports of Chinese mobile Top-8 notebook models in rank Top-8 TV models in rank telecommunications products. 1. Sony SVE1512S7C – 1. Konka LED 32E320N – 2. Lenovo ThinkPad E430C – 2. Changhong LED32B2080 +2 Due to the rapid adoption of smartphone and 3. Acer E1-471G – 3. Sony KLV-32R426A +4 tablets, IDC expects global PC shipments to be 4. -

Brand Association List Is Your Registration up to Date?

Last updated: 7/30/19 Brand Association List Below is the list of brands used in the 2020 Tier Assignment Schedule for Washington’s Electronic Product Recycling Program. Brands are associated with the responsible manufacturer. The manufacturers listed are those Ecology has identified as the brand owners of electronic products covered by this program (computers, monitors, laptops, televisions, portable DVD players, tablets, and e-Readers). Is Your Registration Up to Date? • Manufacturers who own additional brands of covered electronic products not currently registered must add those brands to their registration. • Brand owners of covered electronic products that are not on this list must register as a new participant. • Access your registration by going to our webpage for manufacturers and clicking “Submit my annual registration.” If you have questions, please contact Jade Monroe at 360-407-7157 or [email protected]. Brand Manufacturer 2go PC Computer Technology Link 3D Corporation 3D Corporation 3M Dynapro 3M Touch Systems 4th Dimension Computer 4th Dimension Computer 888 (Chinese Characters) Fry's Electronics, Inc. Abacus Abacus Office Machines ABS ABS Computer Technologies Inc ABS Newegg ACC Tech ACC Tech ACC Tech Angel Computer Systems Inc Access HD GXi International Accu Scan J.C. Penney Corporation, Inc. Accurian General Wireless Operations Inc dba RadioShack Accuvision QubicaAMF Acer Acer America Corp ACI Micro ACI Micro ACW Computer Warehouse of Central Florida, Inc ADEK ADEK Industrial Computers Ademco Honeywell ACS Division ADP ADP ADT ADT LLC dba ADT Security Services ADVENT VOXX International Corp. Affinity Kith Consumer Product Inc. AFUNTA Afunta LLC Last updated: 7/30/19 AG Neovo AG Neovo Technology Corp Agasio Amcrest Technologies LLC AGPTEK Mambate USA, Inc. -

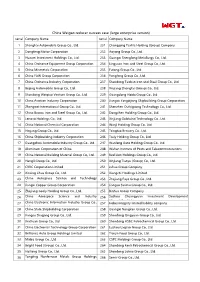

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

UR5U-9000L and 9020L Cable Remote Control

th Introduction Button Functions A. Quick Set-Up Method C. Auto-Search Method E. AUX Function: Programming a 5 G. Programming Channel Control If your remote model has custom-program- 6 Quick Set-up Code Tables 7 Set-up Code Tables TV Operating Instructions For 1 4 STEP1 Turn on the device you want to program- Component mable Macro buttons available, they can be Manufacturer/Brand Set-Up Code Number STEP1 Turn on the Component you want to You can program the channel controls programmed to act as a 'Macro' or Favorite The PHAZR-5 UR5U-9000L & UR5U-9020L to program your TV, turn the TV on. TV CBL-CABLE Converters BRADFORD 043 program (TV, AUD, DVD or AUX). You can take advantage of the AUX func- (Channel Up, Channel Down, Last and Channel button in CABLE mode. This allows is designed to operate the CISCO / SA, STEP2 Point the remote at the TV and press tion to program a 5th Component such as a Numbers) from one Component to operate Quick Number Manufacturer/Brand Manufacturer/Brand Set-Up Code Number BROCKWOOD 116 STEP2 Press the [COMPONENT] button (TV, you to program up to five 2-digit channels, BROKSONIC 238 Pioneer, Pace Micro, Samsung and and hold TV key for 3 seconds. While second TV, AUD, DVD or Audio Component. in another Component mode. Default chan- 0 FUJITSU CISCO / SA 001 003 041 042 045 046 PHAZR-5 Holding the TV key, the TV LED will light AUD, DVD or AUX) to be programmed four 3-digit channels or three 4-digit channels BYDESIGN 031 032 Motorola digital set tops, Plus the majority th nel control settings on the remote control 1 SONY PIONEER 001 103 034 051 063 076 105 and [OK/SEL] button simultaneously STEP1 Turn on the 5 Component you want that can be accessed with one button press. -

TECH EAST – Rough Notes 1/17/18 LVCC – North Hall

TECH EAST – Rough Notes 1/17/18 LVCC – North Hall Company Booth Notes car as companion, butler, pet—AI—Design, mileage and handling 1 Toyota 6906 are secondary to what is the experience in the car and of the car. 2 NVdia 7019 Largest Chip manufacuturer for AI, VW Buzz (electric) Holodeck Car German Technical Car (competitor to Tesla) 3 Byton 6525 el Cell Technology, Charge Rage (Talk about Smart Cities in 4 Hyundia 6329 Westgate Hotel) 5 Ford 5002 (Smart cities/screen) “Roads are for driving, streets are for living” LVCC – Central Hall Company Booth Notes Digital Wall Paper OLED TV corner Comparitive Screens (4k, HDR, HFR, 8K, Image recognition and sharpening magic filters.) Artwork 1 LG 11100 Embedded Google assistant ThinQ (More Future Home and AI play) GE ranges that are Hey 2 Haier 11421 Googalized/Alexa The Stove is the hub of the smart home. EyeCandy World Cup Sponosr, Men in Blazers, Alexa Enable TVs Just ask Alexa. Battle for the home OS (TV and Interactions) Ecosystem Battle. 3 Hisense 10039 Intel 10048 4 Zones—5G, VR, AI and AD CityBeacon/Smart Cities 5 Intel 10048 AI/Urban Campus - power of the chip in all things. 6 Qualcomm 51116 Wearables, Mobile VR—discussion of 5G is coming, Property of StoryTech – not for press or media consumption - working document for CES® 2018 Tour Program LVCC – South Hall Company Booth Notes Smart Dog Eco System - total dog solution, doggie door, collar - 1 Alibaba 20206 activity tracker, food dispenser Venetian Blinds - each blind is a solar panel - sends power into the 2 Kodak 20612 house and grid -

Harvest Funds (Hong Kong) Etf (An Umbrella Unit Trust Established in Hong Kong)

HARVEST FUNDS (HONG KONG) ETF (AN UMBRELLA UNIT TRUST ESTABLISHED IN HONG KONG) HARVEST MSCI CHINA A INDEX ETF (A SUB-FUND OF THE HARVEST FUNDS (HONG KONG) ETF) SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT 1ST JANUARY 2016 TO 30TH JUNE 2016 www.harvestglobal.com.hk HARVEST MSCI CHINA A INDEX ETF (A SUB-FUND OF THE HARVEST FUNDS (HONG KONG) ETF) CONTENTS PAGE Report of the Manager to the Unitholders 1 - 2 Statement of Financial Position (Unaudited) 3 Statement of Comprehensive Income (Unaudited) 4 Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Unitholders (Unaudited) 5 Statement of Cash Flows (Unaudited) 6 Investment Portfolio (Unaudited) 7 – 29 Statement of Movements in Investment Portfolio (Unaudited) 30 – 75 Performance Record (Unaudited) 76 Underlying Index Constituent Stocks Disclosure (Unaudited) 77 Report on Investment Overweight (Unaudited) 78 Management and Administration 79 - 81 RESTRICTED HARVEST MSCI CHINA A INDEX ETF (A SUB-FUND OF THE HARVEST FUNDS (HONG KONG) ETF) REPORT OF THE MANAGER TO THE UNITHOLDERS Fund Performance A summary of the performance of the Sub-Fund1 is given below (as at 30 June 2016): Harvest MSCI China A Index ETF 1H-2016 (without dividend reinvested) MSCI China A Index2 -17.61% Harvest MSCI China A Index ETF NAV-to-NAV3 (RMB Counter) -17.60% Harvest MSCI China A Index ETF Market-to-Market4 (RMB Counter) -19.54% Harvest MSCI China A Index ETF NAV-to-NAV3 (HKD Counter) -18.51% Harvest MSCI China A Index ETF Market-to-Market4 (HKD Counter) -20.82% Source: Harvest Global Investments Limited, Bloomberg. 1 Past performance figures shown are not indicative of the future performance of the Sub-Fund. -

Annual Report DBX ETF Trust

May 31, 2021 Annual Report DBX ETF Trust Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF (ASHR) Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF (ASHS) Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF (CN) Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF (ASHX) DBX ETF Trust Table of Contents Page Shareholder Letter ....................................................................... 1 Management’s Discussion of Fund Performance ............................................. 3 Performance Summary Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 6 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 8 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 10 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 12 Fees and Expenses ....................................................................... 14 Schedule of Investments Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 15 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 20 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 28 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 33 Statements of Assets and Liabilities ........................................................ 42 Statements of Operations ................................................................. 43 Statements of Changes in Net -

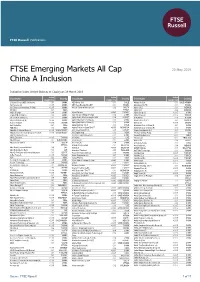

FTSE Emerging Markets All Cap China a Inclusion

FTSE Russell Publications FTSE Emerging Markets All Cap 20 May 2019 China A Inclusion Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 29 March 2019 Index Index Index Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country weight (%) weight (%) weight (%) 21Vianet Group (ADS) (N Shares) 0.01 CHINA AES Gener S.A. 0.01 CHILE Almarai Co Ltd 0.01 SAUDI ARABIA 360 Security (A) <0.005 CHINA AES Tiete Energia SA UNIT 0.01 BRAZIL Alpargatas SA PN 0.01 BRAZIL 361 Degrees International (P Chip) <0.005 CHINA African Rainbow Minerals Ltd 0.02 SOUTH Alpek S.A.B. 0.01 MEXICO 3M India 0.01 INDIA AFRICA Alpha Bank 0.04 GREECE 3SBio (P Chip) 0.04 CHINA Afyon Cimento <0.005 TURKEY Alpha Group (A) <0.005 CHINA 51job ADR (N Shares) 0.03 CHINA Agile Group Holdings (P Chip) 0.04 CHINA Alpha Networks <0.005 TAIWAN 58.com ADS (N Shares) 0.12 CHINA Agility Public Warehousing Co KSC 0.04 KUWAIT ALROSA ao 0.06 RUSSIA 5I5j Holding Group (A) <0.005 CHINA Agricultural Bank of China (A) 0.06 CHINA Alsea S.A.B. de C.V. 0.02 MEXICO A.G.V. Products <0.005 TAIWAN Agricultural Bank of China (H) 0.26 CHINA Altek Corp <0.005 TAIWAN Aarti Industries 0.01 INDIA Aguas Andinas S.A. A 0.03 CHILE Aluminum Corp of China (A) 0.01 CHINA ABB India 0.02 INDIA Agung Podomoro Land Tbk PT <0.005 INDONESIA Aluminum Corp of China (H) 0.03 CHINA Abdullah Al Othaim Markets <0.005 SAUDI ARABIA Ahli United Bank B.S.C. -

Fortiextender 2.0.2 Release Notes 36-202-292893-20150918 TABLE of CONTENTS

FortiExtender Release Notes VERSION 2.0.2 TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION http://docs.fortinet.com KNOWLEDGE BASE http://kb.fortinet.com FORUMS https://support.fortinet.com/forum CUSTOMER SERVICE & SUPPORT https://support.fortinet.com FORTIGATE COOKBOOK http://cookbook.fortinet.com TRAINING http://www.fortinet.com/training FORTIGUARD THREAT RESEARCH & RESPONSE http://www.fortiguard.com LICENSE http://www.fortinet.com/doc/legal/EULA.pdf FEEDBACK Email: [email protected] September 18, 2015 FortiExtender 2.0.2 Release Notes 36-202-292893-20150918 TABLE OF CONTENTS Change Log 4 Introduction 5 Supported models 5 What’s new in FortiExtender 2.0.2 5 Special Notices 6 Access point name 6 FortiExtender-100A 6 Netgear AirCard 340U (AT&T) USB modem 6 Novatel 551L (Verizon) and Ovation MC679 (Bell Canada) USB modems 6 Upgrade Information 7 Upgrading from FortiExtender 2.0.1 or later 7 Upgrading from FortiExtender 2.0.0 7 Upgrading from FortiExtender 1.0.0 7 Firmware upgrade procedure 7 Firmware image checksums 8 Novatel MC679 8 Product Integration and Support 9 Modes of operation 9 Connected UTM mode 9 Standalone mode 9 FortiExtender 2.0.2 support 9 USB modem support 10 Resolved Issues 15 Known Issues 16 Limitations 17 Change Log Date Change Description 2015-09-18 Initial Release. 2016-01-18 Updated Upgrade Information. 4 FortiExtender Fortinet, Inc. Introduction This document provides the following information for FortiExtender build 0011. l Supported models l What's new l Special Notices l Upgrade Information l Product Integration and Support l Resolved Issues l Known Issues l Limitations For more information on upgrading your FortiExtender device, see the FortiExtender Administration Guide Supported models FortiExtender 2.0.2 supports the following models: FEX-20B, FEX-100A, and FEX-100B.