Raiding the Future – Impacts of Violent Livestock Theft on Development and an Evaluation of Conflict Mitigation Approaches in Northwestern Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Update

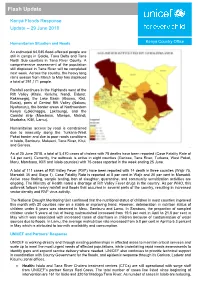

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

Kenya, Groundwater Governance Case Study

WaterWater Papers Papers Public Disclosure Authorized June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA GROUNDWATER GOVERNANCE CASE STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Albert Mumma, Michael Lane, Edward Kairu, Albert Tuinhof, and Rafik Hirji Public Disclosure Authorized Water Papers are published by the Water Unit, Transport, Water and ICT Department, Sustainable Development Vice Presidency. Water Papers are available on-line at www.worldbank.org/water. Comments should be e-mailed to the authors. Kenya, Groundwater Governance case study TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................................. vi ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................ viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................ xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... xiv 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. GROUNDWATER: A COMMON RESOURCE POOL ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2. CASE STUDY BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

Oyiengo, Nathan Amunga (1941–2015)

Image not found or type unknown Oyiengo, Nathan Amunga (1941–2015) SELINA OYIENGO Selina Oyiengo Nathan Amunga Oyiengo was a pastor and administrator in Kenya. Early Life Nathan Amunga Oyiengo was born to Jackton Oyiengo and Rispa Asami on December 23, 1941, in Ebulali Sub- location of Khwisero Location in the then Kakamega District (now Butere-Mumias District) in Western Kenya.1 His father, Jackton, was a prison officer while his mother was a housewife and a small scale businesswoman. His was a big family of one brother and five sisters. His formative years were spent with his parents and siblings in Kakamega, but when he began going to school, he went to live with his father in Nairobi. For little Nathan, life in the city was a new experience, and it was not long before he found himself in trouble.2 During an interview with his children Jack and Selina in August 2015, he narrated how one afternoon while roaming around aimlessly he found himself on the shoulders of a stranger being whisked away to some unknown destination. The man who had grabbed him was so fast that Nathan did not find his voice until a neighbor called out his name asking where he was going with the strange man. Sensing danger, the would-be kidnapper dropped his human cargo and hurriedly explained that he was only playing with the boy. After giving that brief and completely unconvincing explanation of his weird behavior, the man hurriedly walked away and melted into the gathering crowd. Thus, Nathan was saved from a kidnapping that would have completely altered the course of his life.3 After completing his studies at class four level, he proceeded to class five, six, and finally class seven where he sat for another exam and excelled. -

Migrated Archives): Ceylon

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Ceylon Following earlier settlements by the Dutch and Secret and confidential despatches sent to the Secretary of State for the Portuguese, the British colony of Ceylon was Colonies established in 1802 but it was not until the annexation of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 FCO 141/2098-2129: the despatches consist of copies of letters and reports from the Governor that the entire island came under British control. and the departments of state in Ceylon circular notices on a variety of subjects such as draft bills and statutes sent for approval, the publication Ceylon became independent in 1948, and a of orders in council, the situation in the Maldives, the Ceylon Defence member of the British Commonwealth. Queen Force, imports and exports, currency regulations, official visits, the Elizabeth remained Head of State until Ceylon political movements of Ceylonese and Indian activists, accounts of became a republic in 1972, under the name of Sri conferences, lists of German and Italian refugees interned in Ceylon and Lanka. accounts of labour unrest. Papers relating to civil servants, including some application forms, lists of officers serving in various branches, conduct reports in cases of maladministration, medical reports, job descriptions, applications for promotion, leave and pensions, requests for transfers, honours and awards and details of retirements. 1931-48 Secret and confidential telegrams received from the Secretary of State for the Colonies FCO 141/2130-2156: secret telegrams from the Colonial Secretary covering subjects such as orders in council, shipping, trade routes, customs, imports and exports, rice quotas, rubber and tea prices, trading with the enemy, air communications, the Ceylon Defence Force, lists of The binder also contains messages from the Prime Minister and enemy aliens, German and Japanese reparations, honours the Secretary of State for the Colonies to Mr Senanyake on 3 and appointments. -

LODWAR MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN (Idep)

TURKANA COUNTY GOVERNMENT LODWAR MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN (IDeP) 2O18-2022 Table of Contents CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................... vii 1.0 Background Information ...................................................................................................................... vii 1.1 Location and size ................................................................................................................................. vii 1.2 Topography ........................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Climatic condition.................................................................................................................................. 9 1.4 Demographic Structure and Trends ....................................................................................................... 9 1.5 Settlement Patterns ............................................................................................................................ 11 1.6 Socio- Economic Characteristics .......................................................................................................... 11 1.6.1 Dry Land Agriculture ..................................................................................................................... 11 1.6.2 Livestock keeping ........................................................................................................................ -

Turkana County Government Office of the County Executive Finance and Planning Successful Bidders for Prequalification/Registration Fy 2018-2020

TURKANA COUNTY GOVERNMENT OFFICE OF THE COUNTY EXECUTIVE FINANCE AND PLANNING SUCCESSFUL BIDDERS FOR PREQUALIFICATION/REGISTRATION FY 2018-2020 TCG/REG/G1/2018-2019/2019-2020 SUPPLY AND DELIVERY OF BUILDING MATERIALS (OPEN) S/NO BIDDERS NAME TELEPHONE NO: ADDRESS email address 1. ICHEBORE NABO GENERAL SUPPLIES 721949390 P.O BOX 167-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 2 . CHELIS ENTERPRISES 717298119 P.O BOX 532 NAIROBI [email protected] P.O BOX 102251-00101 BROMAK GENERAL MERCHANTS LTD 722665395 [email protected] 3. NAIROBI 4. KADIAKA CONTRACTORS& SUPPLIES CO.LTD 0710485732/0717821147 P.O BOX 139-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 5. SHAMILLO ENTERPRISES LTD 720144364 P.O BOX 19-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 6. ATEKER RESILIENT CONSTRUCTION CO.LTD 729005142 P.O BOX 544-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 7. KATABOI INVESTMENTS LTD 713100319 P.O BOX 554-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 8. NGILUKIA ENTERPRISES LTD 719474720 P.O BOX399-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 9. KEKORONGOLE CONTRACTORS 715870124 P.O BOX106-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 10. DECOS INVESTMENT 721546654 P.O BOX 1939-00100 NAIROBI [email protected] 11. NGAMIA ONE CONSTRACTOR CO.LTD 710238217 P.O BOX561-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 12. GABNA TRADING CO LTD 724524278 P.OBOX .136-30500 LODWAR [email protected] 13. BEUTKO CO . LTD 722140957 P.O.BOX 8400-30100 ELDORET [email protected] P.O.BOX 19393-00100 KAPPEX ENTERPRISES LTD 725410985 [email protected] 14. NAIROBI 15. BARAKA CONTRACTORS LTD 710238217 P.O.BOX 561-30500 LODWAR [email protected] APPROVED BY: REUBEN EBEI MCIPS,MBA, LLM DIRECTOR SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT SERVICES TURKANA COUNTY GOVERNMENT SIGNATURE:…… …………………………………………… DATE:… ………………………………………. -

KENYA KENYA Lodwar (Turkana)

KENYA KENYA Lodwar (Turkana) Eldoret Nairobi KENYA Lodwar (Turkana) Eldoret Nairobi Friends Theological College, Kaimosi Lodwar (Turkana) Eldoret Nairobi Lugulu Friends Hospital Kaptama Friends Lodwar Church and Clinic, (Turkana) Mount Elgon Eldoret Nairobi Seeds Project, Kitale Lodwar (Turkana) Eldoret Nairobi Turkana Friends Mission: Lodwar (Turkana) Katapakori Friends Church Nekwei Friends Church Eldoret Lokoyo Friends Nairobi Church Lodwar Ivona Friends (Turkana) Church, Chavakali Yearly Meeting Eldoret Nairobi Lodwar (Turkana) Eldoret Nairobi Africa Ministries Office of Friends United Meeting, Kisumu Lodwar (Turkana) Eldoret Nairobi Moffat Bible College, Rift Valley Academy, Kijabe Hospital KENYAN WORSHIP Turkana Friends Lodwar (Turkana) Mission Eldoret Nairobi Vision Statement To reach, equip and energize the pastoralist community of Turkana spiritually, mentally and physically for the Glory of God. TURKANA FRIENDS MISSION . Staff of 19 . 14 churches (6 with structures) . Operate 10 schools . Started one church per year since 2009 . Mission budget is $3,000 per month "God is using our legs to reach people for Christ… These sandals have led many people to Jesus!" - Pastor Simon "There are times when the support becomes low, but we continue with zeal because we know that the God we serve knows how to provide a meal." - Jackson (board member) "We can go hungry for two days, three days, but God gives us strength." - Alice (board member) "The gospel is expensive. It cost Jesus his life. Should it come cheap to us?" - John Moru, director Evangelism and Discipleship Multiplication of Locally Small Business Churches Sustainable Training Ministry Sending New Leadership Leaders Development Evangelism and Discipleship Multiplication of Locally Small Business Churches Sustainable Training Ministry Sending New Leadership Leaders Development There are now about 2,000 Friends Churches in Kenya. -

Climate Change in Kenya

HEAD body CLIMATE CHANGE IN KENYA: focus on children © UNICEF/François d’Elbee INTRODUCTION 1 KENYA: CLIMATE CHANGE 3 MOMBASA 5 GARISSA 7 CONTENTS LODWAR 9 NAIROBI 11 KISUMU 13 NAKURU 15 KERICHO 17 NYERI 19 CONCLUSION 21 APPENDIX: CLIMATE TABLES 23 REFERENCES 27 ENDNOTES AND ACRONYMS 28 © UNICEF/François d’Elbee INTRODUCTION “Our home was UNICEF UK and UNICEF Kenya have produced this case study to destroyed by the floods highlight the specific challenges for and we have nothing children related to climate change left. My parents cannot in Kenya; bringing climate models to life with stories from children even afford to pay my in different regions. The study older siblings’ school fees provides examples of how UNICEF can support children in Kenya to since we have no cows adapt to and reduce the impact of left to sell.” climate change. Nixon Bwire, age 13, Tana River Climate change is already having a significant effect on children’s well-being in Kenya. The impact on children is likely to increase significantly over time; the extent of the impact depends on how quickly and successfully global greenhouse gas emissions are reduced as well as the ability to adapt to climate change. Climate models show the range of likely future impacts. The projections in this paper use the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the University of Oxford School of Geography and Environment interpretation of scenario A2 from the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES). They used an ensemble of 15 models to arrive at the figures used here. Scenario A2 posits regionally oriented economic development and has slower and more fragmented economic and technological development than other scenarios. -

Request for Information on Vetting of National Police Service Officers

THE NATIONAL POLICE SERVICE COMMISSION REQUEST FOR INFORMATION ON VETTING OF NATIONAL POLICE SERVICE OFFICERS The National Police Service Commission (NPSC) is a corporate body established under Article 246 of the Constitution of Kenya and enacted through an Act of Parliament No.30 of 2011. In exercising its mandate as provided under Section 7 (2) and (3) of the National Police Service Act, 2011, the Commission intends to conduct vetting of all officers to assess their suitability and competence and to discontinue the service of any police officer who fails in the vetting. The Commission requests members of public and institutions to participate in this process by submitting any relevant information which may assist in the determination of suitability and competence of the National Police Service Officers listed below:- A. SENIOR ACPs AND ACPs (TO BE VETTED IN NAIROBI) S/NO: NAME P/NO: RANK STATION S/NO: NAME P/NO: RANK STATION 1. STEPHEN K. ARAP SOI 213565 S/ACP GSU H/Q 3. JOHNSON KORIR KIBOR 214803 ACP KAPU 2. PAUL JIMMIE NDAMBUKI 218247 ACP FRANCE 4. JOHN GACHUNGU GACHOMO 219052 ACP LIBERIA B. SSPs & SPs FOR RIFT VALLEY REGION S/NO: NAME P/NO: RANK STATION S/NO: NAME P/NO: RANK STATION 1. ABAGARO BAGAYO GUYO 219032 SSP OCPD SAMBURU CENTRAL 30. FRANCIS W. NGANGA 86009202 SSP KEIYO NORTH 2. ABDALLAH K. MWATSEFU 218153 SSP CCIO LAIKIPIA 31. FREDRICK MUTHAMA LAI 219536 SSP OCPD NJORO 3. ADAN K. ABDULLAHI 85003368 SSP BOMET COUNTY 32. FREDRICK ODHIAMBO OCHING 230341 SSP OCPD KEIYO NORTH 4. APOLLO B. ABUNYA 85002087 SSP TURKANA WEST 33. -

Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect Occasional Paper Series No. 4, December 2013 “ R2P in Practice”: Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya Abdullahi Boru Halakhe The Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect was established in February 2008 as a catalyst to promote and apply the norm of the “Responsibility to Protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Through its programs, events and publications, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect is a resource and a forum for governments, international institutions and non-governmental organizations on prevention and early action to halt mass atrocity crimes. Acknowledgments: This Occasional Paper was produced with the generous support of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany. About the Author: Abdullahi Boru Halakhe is a security and policy analyst on the Horn of Africa and Great Lakes regions. Abdullahi has represented various organizations as an expert on these regions at the UN and United States State Department, as well as in the international media. He has authored and contributed to numerous policy briefings, reports and articles on conflict and security in East Africa. Previously Abdullahi worked as a Horn of Africa Analyst with International Crisis Group working on security issues facing Kenya and Uganda. As a reporter with the BBC East Africa Bureau, he covered the 2007 election and subsequent violence from inside Kenya. Additionally, he has worked with various international and regional NGOs on security and development issues. Cover Photo: Voters queue to cast their votes on 4 March 2013 in Nakuru, Kenya.