Metamorphoses: `The Transformation and Transmutation of the Arcadian Dream'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

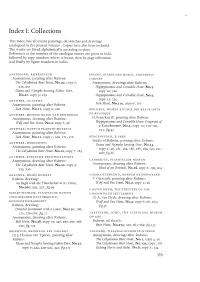

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections This index lists ail extant paintings, oil sketches and drawings catalogued in the present volume . Copies have also been included. The works are listed alphabetically according to place. References to the number of the catalogue entries are given in bold, followed by copy numbers where relevant, then by page references and finally by figure numbers in italics. AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM BRUGES, STEDEEÏJKE MUSEA, STEINMETZ- Anonymous, painting after Rubens : CABINET The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .20, copy 6; Anonymous, drawings after Rubens: 235, 237 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, Diana and Nymphs hanting Fallow Deer, copy 12; 120 N o.21, copy 5; 239 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, cop y 13; 120 ANTWERP, ACADEMY Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o.ne, copy 6; 177 Lion Hunt, N o.11, copy 2; 162 BRUSSELS, MUSÉES ROYAUX DES BEAUX-ARTS DE BELGIQUE ANTWERP, MUSEUM MAYER VAN DEN BERGH Anonymous, drawing after Rubens: H.Francken II, painting after Rubens: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt: Fragment of W olf and Fox Hunt, N o .2, copy 7; 96 a Kunstkammer, N o.5, copy 10; 119-120, ANTW ERP, MUSEUM PLANTIN-M O RETUS 123 ;fig .4S Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o .n , copy 1; 162, 171, 178 BÜRGENSTOCK, F. FREY Studio of Rubens, painting after Rubens: ANTWERP, RUBENSHUIS Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer, N o .13, Anonymous, painting after Rubens : copy 2; 46, 181, 182, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .12, copy 7; 185 208; fig.S6 ANTWERP, STEDELIJK PRENTENKABINET Anonymous, -

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

The Zodiac: Comparison of the Ancient Greek Mythology and the Popular Romanian Beliefs

THE ZODIAC: COMPARISON OF THE ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY AND THE POPULAR ROMANIAN BELIEFS DOINA IONESCU *, FLORA ROVITHIS ** , ELENI ROVITHIS-LIVANIOU *** Abstract : This paper intends to draw a comparison between the ancient Greek Mythology and the Romanian folk beliefs for the Zodiac. So, after giving general information for the Zodiac, each one of the 12 zodiac signs is described. Besides, information is given for a few astronomical subjects of special interest, together with Romanian people believe and the description of Greek myths concerning them. Thus, after a thorough examination it is realized that: a) The Greek mythology offers an explanation for the consecration of each Zodiac sign, and even if this seems hyperbolic in almost most of the cases it was a solution for things not easily understood at that time; b) All these passed to the Romanians and influenced them a lot firstly by the ancient Greeks who had built colonies in the present Romania coasts as well as via commerce, and later via the Romans, and c) The Romanian beliefs for the Zodiac is also connected to their deep Orthodox religious character, with some references also to their history. Finally, a general discussion is made and some agricultural and navigator suggestions connected to Pleiades and Hyades are referred, too. Keywords : Zodiac, Greek, mythology, tradition, religion. PROLOGUE One of their first thoughts, or questions asked, by the primitive people had possibly to do with sky and stars because, when during the night it was very dark, all these lights above had certainly arose their interest. So, many ancient civilizations observed the stars as well as their movements in the sky. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles Thomasf

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles ThomasF. Hedin It was Pierre Francastel who christened the most famous the west (Figs. 1, 2, both showing the expanded zone four program of sculpture in the history of Versailles: the Grande years later). We know the northern end of the axis as the Commande of 1674.1 The program consisted of twenty-four Allee d'Eau. The upper half of the zone, which is divided into statues and was planned for the Parterre d'Eau, a square two identical halves, is known to us today as the Parterre du puzzle of basins that lay on the terrace in front of the main Nord (Fig. 2). The axis terminates in a round pool, known in western facade for about ten years. The puzzle itself was the sources as "le rondeau" and sometimes "le grand ron- designed by Andre Le N6tre or Charles Le Brun, or by the deau."2 The wall in back of it takes a series of ninety-degree two artists working together, but the two dozen statues were turns as it travels along, leaving two niches in the middle and designed by Le Brun alone. They break down into six quar- another to either side (Fig. 1). The woods on the pool's tets: the Elements, the Seasons, the Parts of the Day, the Parts of southern side have four right-angled niches of their own, the World, the Temperamentsof Man, and the Poems. The balancing those in the wall. On July 17, 1664, during the Grande Commande of 1674 was not the first program of construction of the wall, Le Notre informed the king by statues in the gardens of Versailles, although it certainly was memo that he was erecting an iron gate, some seventy feet the largest and most elaborate from an iconographic point of long, in the middle of it.3 Along with his text he sent a view. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way.