Scrutiny Review of Regeneration Funding – Area Summaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

74 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

74 bus time schedule & line map 74 Rotherham - She∆eld View In Website Mode The 74 bus line (Rotherham - She∆eld) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Rotherham Town Centre <-> Waverley: 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM (2) Waverley <-> Rotherham Town Centre: 7:47 AM - 5:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 74 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 74 bus arriving. Direction: Rotherham Town Centre <-> Waverley 74 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Rotherham Town Centre <-> Waverley Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday Not Operational Rotherham Interchange/B10, Rotherham Town Monday 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM Centre Tuesday 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM Corporation Street/Market Street, Rotherham Town Centre Wednesday 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM Corporation Street, Rotherham Thursday 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM Westgate/Unity Place, Rotherham Town Centre Friday 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM 28-32 Westgate, Rotherham Saturday 8:32 AM - 6:55 PM Canklow Road/Alma Road, Rotherham Town Centre Alma Road, Rotherham Canklow Road/Mill Street, Canklow 74 bus Info Direction: Rotherham Town Centre <-> Waverley Canklow Road/Jubilee Street, Canklow Stops: 29 Trip Duration: 21 min Canklow Road/Warden Street, Canklow Line Summary: Rotherham Interchange/B10, Rotherham Town Centre, Corporation Street/Market Canklow Road/Canklow Hill Road, Canklow Street, Rotherham Town Centre, Westgate/Unity Place, Rotherham Town Centre, Canklow Road/Alma Centenary Way/West Bawtry Road, Canklow Road, Rotherham Town Centre, Canklow Road/Mill Street, Canklow, Canklow Road/Jubilee Street, Bawtry -

NHS Rotherham GP Commissioning Localities - January 2011

NHS Rotherham GP Commissioning Localities - January 2011 PA Rep STUART LAKIN Central North GP Lead Other GP's with in the practice Practice Name Practice Manager Address Telephone List Size Kirsty Gillgrass Dr Everett, Brynes, Jones, Bhattacharya, Woodstock Bower Group PracticeBernadette Conway Kimberworth Road, Rotherham, South 0844 8151956 11524 Adrian Cole, Rihal, Saeed Yorkshire, S61 1AH Naresh PATEL Dr Stott, Martin, Cullen, Sanders, Kacker, Broom Lane Medical PracticeMartyn Heeley 70 Broom Lane, Rotherham, S60 3EW 0844 477 39 79 12574 George, Thomas Shrinivas Ravula Dr M Husain Greasbrough Medical Centre Claire Astbury Greasbrough, Greenside, Rotherham, South 01709 559955 3269 Yorkshire, S61 4PT Charles Collinson Dr Myers, Barragry, Evans Greenside Surgery Carole Dalling Munsbrough Rise, Greasborough, 0845 1240887 5187 Rotherham, South Yorkshire, S61 4RB Total 32554 PA Rep GOVINDER BHOGAL RICHARD RUSSELL Central Two Practice Practice Name Practice Manager Address Telephone List Size Tariq Ahmed Dr Nazir, Jubb, Ghaebi and Chikthimmah Kilnhurst Surgery Steve Hindle Magna Lane, Dalton, Rotherham, South 0845 1244746 7011 (Deputy) Yorkshire, S65 4HH Nayyer Ishaque Dr Iqbal Dalton Health Centre Angela Madden Magna Lane, Dalton, Rotherham, South 0845 1266430 2040 Yorkshire, S65 4HH Hilal Jarjis Badsley Moor Lane Surgery Julie Gibson 292 Badsley Moor Lane, Rotherham, South 0845 1222276 2464 Yorkshire, S65 2QW Saheel BATT Dr A Goni and Dr M S Chauhdry Shakespeare Road Surgery Diane Batham 50 Shakespeare Road, Eastwood, 0845 1213122 4879 -

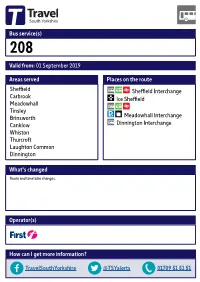

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas

Bus service(s) 208 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Carbrook Ice Sheffield Meadowhall Tinsley Brinsworth Meadowhall Interchange Canklow Dinnington Interchange Whiston Thurcroft Laughton Common Dinnington What’s changed Route and timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 208 01/02/2019 Scholes Parkgate Dalton Thrybergh Braithwell Ecclesfield Ravenfield Common Kimberworth East Dene Blackburn ! Holmes Meadowhall, Interchange Flanderwell Brinsworth, Hellaby Bonet Lane/ Bramley Wincobank Brinsworth Lane Maltby ! Longley ! Brinsworth, Meadowhall, Whiston, Worrygoose Lane/Reresby Drive ! Ñ Whitehill Lane/ Meadowhall Drive/ Hooton Levitt Bawtry Road Meadowhall Way 208 Norwood ! Thurcroft, Morthen Road/Green Lane Meadowhall, Whiston, ! Meadowhall Way/ Worrygoose Lane/ Atterclie, Vulcan Road Greystones Road Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Green Arbour Road ! Pitsmoor Atterclie Road/ Brinsworth, Staniforth Road Comprehensive School Bus Park ! Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Peter Street Laughton Common, ! ! Station Road/Hangsman Lane ! Atterclie, AtterclieDarnall Road/Shortridge Street ! ! ! Treeton Dinnington, ! ! ! Ulley ! Doe Quarry Lane/ ! ! ! Dinnington Comp School ! Sheeld, Interchange Laughton Common, Station Road/ ! 208! Rotherham Road 208 ! Aughton ! Handsworth ! 208 !! Manor !! Dinnington, Interchange Richmond ! ! ! Aston database right 2019 Swallownest and Heeley Todwick ! Woodhouse yright p o c Intake North Anston own r C Hurlfield ! data © y Frecheville e Beighton v Sur e South Anston c ! Wales dnan ! r O ! ! ! ! Kiveton Park ! ! ! ! ! ! Sothall ontains C 2019 ! = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop 24 hour clock 24 hour clock Throughout South Yorkshire our timetables use the 24 hour clock to avoid confusion between am and pm times. -

Rotherham Primary Care Estates Strategy V8

Rotherham Clinical Commissioning Group gy Amended November 2020 Intentionally Left Blank Rotherham Primary Care Estates Strategy 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6.4.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 6.4.3. Central North Locality Estates Prioritisation 2. INTRODUCTION 6.5. Health Village / Central Locality 6.5.1. Property Assessment 3. STRATEGIC CONTEXT 6.5.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 3.1. National Policy Context 6.5.3. Health Village / Central Locality Estate Prioritisation 3.2. Five Year Forward View 6.6. Maltby & Wickersley Locality 3.3. Delivering the Five Year Forward View 6.6.1. Premises Assessment 3.4. General Practice Forward View 6.6.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 3.5. Next Steps on Five Year Forward View 6.6.3. Maltby & Wickersley Locality Estates Prioritisation 6.7. Wentworth South Locality 4. ROTHERHAM COMMISSIONING PRIORITIES, ORGANISATIONS AND 6.7.1. Premises Assessment STRATEGIC PARTNERS 6.7.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 4.1. Health and Social Pen Picture of Rotherham 6.7.3. Wentworth South Locality Estates Prioritisation 4.1.1. Socio-economic Profile 6.8. Wath / Swinton Locality 4.1.2. Housing 6.8.1. Premises Assessment 4.1.3. Demographic Profile 6.8.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 4.1.4. Health Needs 6.8.3. Wath / Swinton Locality Estates Prioritisation 4.2. Clinical Commissioning Groups 4.3. Local Authorities 7. FINANCIAL SUMMARY 4.4. Providers / Third Sector 4.5. South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw Integrated Care System (STP) 8. 2020 UPDATE 5. REVIEW OF THE PRIMARY CARE ESTATE ACROSS ROTHERHAM 5.1. -

Former County of South Yorkshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2002 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects Yorkshire & Humberside Region FORMER COUNTY OF SOUTH YORKSHIRE Doncaster 3/1690 (E.04.J004) SK 49409600 FIRSBY HALL FARM, CONISBROUGH. An Archaeological Watching Brief at Firsby Hall Farm, Conisbrough. South Yorkshire Davies, G. Sheffield : ARCUS, 2002, 26pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: ARCUS A watching brief was carried out on the site. No undisturbed deposits and no in situ structures were identified. There were numerous fragments of burnt clay probably from kilns, suggesting there presence nearby. These remains were identified as likely to be related to the medieval pottery production site previously identified in Firsby. [Au(adp)] Archaeological periods represented: MD 3/1691 (E.04.J002) SE 62000410 MARKHAM MAIN RESTORATION PROJECTS, DONCASTER Markham Main Restration Project. Doncaster, South Yorkshire Archaeological Services WYAS Morley : Archaeological Services WYAS, 2002, 16pp, pls, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Services WYAS An archaeological watching brief was maintained during part of the landscaping for the Markham Main Restoration Project. The Groundworks proved to be less intrusive than expected and no features or deposits of an archaeological origin were identified. [Au(abr)] 3/1692 (E.04.H001) SE 53691203 ST HELENS CHURCH, BURGHWALLIS St Helen's Church, Burghwallis, South Yorkshire Dennison, E Beverley : Ed Dennison Archaeological Services, 2002, 21pp, colour pls, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: Ed Dennison Archaeological Services An archaeological watching brief was carried out on groundworks at the site. A pit was recorded containing a childs stone coffin, covered by two undecorated stone slabs. The remains of a slightly curved wall just to the north of the coffin was also observed. -

Rotherham Unique Reference Number

INSPECTION REPORT CANKLOW WOOD PRIMARY SCHOOL Canklow, Rotherham, South Yorkshire LEA area: Rotherham Unique reference number: 131696 Headteacher: Mr A Clark Lead inspector: Mr J R Francis Dates of inspection: 8th March 2004 Inspection number: 255705 Inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2004 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. Canklow Wood Primary School - 2 INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Primary School category: Community Age range of pupils: 3 – 11 years Gender of pupils: Mixed Number on roll: 177 plus 17 part-time in the nursery School address: Wood Lane Canklow Rotherham South Yorkshire Postcode: S60 2XJ Telephone number: 01709 828405 Fax number: 01709 837873 Appropriate authority: Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Mrs M Sheard Date of previous inspection: 22nd March 1999 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SCHOOL This average sized primary school has 177 pupils in six classes and 17 children who attend the nursery part-time. There are a similar number of boys and girls. The school also houses a Learning Centre funded through the Excellence in Cities project1. -

Nnfoi 200 Nd

NNFOI_ND Property Address Liable Party Contact Address Rateable Value C/O Capa Audit & Property Advisors, Audit ., Poplar Way, Catcliffe, Rotherham, South Yorkshire, Woolworths P L C - In Department, Po Box 29416, Glasgow, S60 5TR Administration G67 1XU £1,220,000.00 ., Greasbrough Street, Rotherham, South Yorkshire, Oakgate House, 25 Market Street, S60 1LQ Oakgate Rotherham Llp Wetherby, LS22 6LQ £377,500.00 Building 36, Meadows Road, Wath Upon Dearne, Rotherham, South Yorkshire, S63 5DJ Lazarus Properties Ltd 3 Lazarus Court, Doncaster, DN1 3NF £320,000.00 C/O C B Richard Ellis Portfolio Management , 2nd Floor , St Martin'S Town Mills, Canklow Road, Rotherham, South Court, 10 Paternoster Row, London, Yorkshire, S60 2JG Premier Foods Group Ltd EC4M 7HP £305,000.00 C/O Pendragon Plc - Property Dept, Loxley House, 2 Oakwood Court Little ., Great Eastern Way, Parkgate, Rotherham, South Andre Baldet Ltd T/A Evans Oak Drive, Annesley, Nottingham, NG15 Yorkshire, S62 6JD Halshaw 0DR £300,000.00 Unit 1 - Mansells, Adwick Park, Wath Upon Dearne, Cert Octavian House, St Martins Road, Rotherham, South Yorkshire, S63 5NB Cert Octavian Plc Hoddesdon, Herts, EN11 0BT £285,000.00 M F I Group Ltd (In C/O M C R, 43/45 Portman Square, Unit 9, Beale Way, Parkgate, Rotherham, S62 6EJ Administration) London, W1H 6LY £272,500.00 27 29, College Street, Rotherham, South Yorkshire, Nations House, 103 Wigmore Street, S65 1AG G E P (North) Ltd London, W1U 1QS £209,000.00 C/O Robert Smith Financial Management Warehouse, (Former Gloystarne Ltd), Don Street, The -

Strategic Green Belt Review April 2012

Rotherham local plan Rotherham Strategic Green Belt Review April 2012 www.rotherham.gov.uk Rotherham Strategic Green Belt Review Contents 1. Introduction & Need for the Study ....................................................................................................2 2. Aim of the Study..................................................................................................................................2 3. Scope....................................................................................................................................................3 4. Planning Policy Context .....................................................................................................................4 5. Methodology ........................................................................................................................................7 6. Strategic Green Belt Review : Informing Local Plan Preparation .............................................12 7. Results................................................................................................................................................13 8. Conclusion..........................................................................................................................................13 Appendix 1 – Methodology Consultation...............................................................................................15 Appendix 2 – Stage 2: Criteria to assess parcels against Green Belt purposes 1-4 .....................22 Appendix 3 -

South Yorkshire 2019 Flood Disaster Interim Evaluation Report

South Yorkshire Flood Disaster Interim Evaluation Report Table of Contents 1. Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 3. Background .................................................................................................................... 5 4. Immediate Impact ......................................................................................................... 6 5. The Aftermath ............................................................................................................... 9 6. Responses of the Authorities, Charities and other Agencies to the disaster .......... 13 7. Effectiveness of SYCF’s response to the Disaster ...................................................... 18 South Yorkshire 2019 Flood Disaster Relief Interim Evaluation Report Page 2 of 21 1. Purpose This is an interim report to inform and update our donors, communities and other stakeholders about the actions and strategic approach taken by South Yorkshire’s Community Foundation (SYCF) following the floods of November 2019 in the South Yorkshire region. The report also details the continuing efforts to support affected local communities by South Yorkshire’s Community Foundation in partnership with the four Local Authorities, community groups and representatives, Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), -

Hope Construction Materials How to Contact Us

Hope Construction Materials How to contact us Scotland North Office Motherwell Office Gateshead Address Maxim Business Park, Maxim 1 – 1st Floor, Address 2nd Floor, Building 7, Queens Park, Queensway, 2 Parklands Way, Eurocentral, Motherwell TeamValley, Gateshead NE11 OQD ML1 4WR Customer enquiries 0845 5201 655 Customer enquiries 0845 5201 725 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Plants Plants Cloddach Falkirk Livingston Barrow in Furness Garstang Northallerton Dalkeith Glasgow Paisley Bedlington Gateshead Penrith Dumbarton Greenock Port Dundas Bishop Auckland Goole Pocklington Dumfries Inverness St Boswells Boroughbridge Keighley Scorton Dunbar Bradford Kendal Scotswood Brighouse Hartlepool Stockton Burnley Howdon Thornton Carlisle Hull Wetherby Dunald Mill Leeds Yeadon Durham Marfield York Featherstone Middlesbrough Central South West Office Doncaster Office Bristol Address First Floor, Icon Building, First Point, Balby Carr Address 2430/2440 The Quadrant, Aztec West, Bank, Donaster DN4 5JQ Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4AQ Customer enquiries 0845 5201 755 Customer enquiries 0845 5201 855 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Plants Plants Abergele Finningley Pye Bridge Aldermaston Coleford Llanelli Alrewas Four Ashes Retford Andover Exeter Pembroke Dock Ashbury Grantham Rochdale Bournemouth Eysey Manor Portsmouth Ashfield Ilkeston Scunthorpe Bridgend Flax Bourton Southampton Barnsley Immingham Shawell Briton Ferry Gloucester Tongwynlais -

Code for Sustainable Homes Level 4 Rother View Road.Pdf

Planning for Climate Change Case Study Code for Sustainable Homes Level 4, Rother View Road, Canklow, Rotherham Local authority area: Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council Stakeholders: Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council – Neighbourhoods, Development Management; Synergy Housing Solutions (developer registered provider), Rider Levett Bucknall (employers agent), Acanthus WSM Architects (architect), Met Consulting (engineer), Wates Living Space (contractor). Summary To use planning policy to increase the levels of renewable energy generated on-site and in doing so assist in meeting national and regional targets for renewable energy generation. Key learning points Ensure that all design options for land retainment and stabilisation are investigated and the most viable option determined prior to commencement on site. Ensure good communications are maintained with the local community during the construction phase to resolve any conflicts. It is imperative that the main contractor and architect resolve any build ability issues prior to commencement on site to prevent any effect on the construction programme. The client’s design brief must be definitive and unambiguous. The client’s representatives need to be focused throughout the development to ensure that it is delivered in accordance with the tender documentation and work with the main contractor to agree any changes to the specification. Sufficient time must be allowed for all parties to consider and agree alternative design proposals. Compliance with the requirements of Lifetime Homes meant that bathroom / shower rooms were provided on each floor, with the living space at ground and kitchen/dining at first floor. Include sufficient contingencies for site abnormalities. Background 29 new dwellings providing 12no. 3 bed units, 16no. -

How to Find Us

How to Find Us Address Voluntary Action Rotherham The Spectrum Coke Hill Rotherham S60 2HX Tel: 01709 829821 Fax: 01709 829822 Email: [email protected] Web: www.varotherham.org.uk Public Transport Trains Rotherham Central is well serviced by trains from Sheffield, Doncaster, Leeds and other stations. See the National Rail Enquires Website for more information (www.nationalrail.co.uk/stations/RMC/details.html). From the train station you can walk, take a taxi or go to Rotherham Interchange and catch a bus to Voluntary Action Rotherham. If you take the bus, turn right as you leave the train station – you will see the interchange across the road on your left. Buses Buses from across South Yorkshire and beyond run to and from the Rotherham Interchange. For more information contact South Yorkshire Travel (Tel: 01709 515151, Web: www.travelsouthyorkshire.com) or Travel Line ( Tel: 0871 200 22 33, Web: www.yorkshiretravel.net). Bus Services to Voluntary Action Rotherham and The Spectrum A good number of buses run very close to Voluntary Action Rotherham and The Spectrum. Ask the driver to stop at the nearest bus stop to Dusty Miller’s Voluntary Action Rotherham The Spectrum, Coke Hill, Rotherham S60 2HX Tel: 01709 829821 Fax: 01709 829822 Website: www.varotherham.org.uk Canklow Road: 73 (First) Rotherham, Canklow, Brinsworth, Treeton, Catcliffe, Waverley, Handsworth, Richmond, Manor Top, Sheffield 74 (First) Sheffield, Norfolk Park, Manor Top, Handsworth, Catcliffe, Waverley, Canklow, Brinsworth, Rotherham Sheffield Road: X1 (First) Sheffield, Attercliffe, Meadowhall, Tinsley, Rotherham, Herringthorpe, Wickersley, Maltby Walking Voluntary Action Rotherham and The Spectrum are accessible on foot from the centre of Rotherham including the train station and bus interchange.