Corruption in India: Bridging Research Evidence and Policy Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uttarakhand Lokayukta Bill, 2011 [Uttarakhand Bill No

THE UTTARAKHAND LOKAYUKTA BILL, 2011 [UTTARAKHAND BILL NO. OF 2011] A Bill to establish an independent authority to investigate offences under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 so as to detect corruption by expeditious investigation and to prosecute offenders and redressal of certain types of public grievances and to provide protection to whistleblowers. Be it enacted by Legislative Assembly of Uttarakhand in the Sixty-second year of the Republic of India as follows:- CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY Short title, 1. (1) This Act may be called the Uttarakhand Lokayukta Act, 2011. commencement (2) For the purpose of preparations, the provisions of the Act shall and extent come into force at once and the Act shall be operationalised within 180 days of its securing assent from the Governor of Uttarakhand. (3) It extends to the whole of the State of Uttarakhand. Definitions 2. In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires:- (a) “Board” means the Chairperson and the other members of the Lokayukta collectively. (b) “Complaint” means an allegation of corruption or a request by whistleblower for protection or a request for redressal of certain grievances covered under this Act. (c) “Lokayukta” means and includes, (i) The Board; (ii) Benches constituted under this Act and performing functions under this Act; (d) “Lokayukta Bench” means a Bench of two or more members of the 1 Lokayukta with or without the Chairperson acting together in respect of any matter in accordance with the regulations framed under the Act. Each bench shall have a member with -

Corrupt Practices in India: No Payoff

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 20 Number 2 Article 5 1-1-1998 Corrupt Practices in India: No Payoff Toral Patel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Toral Patel, Corrupt Practices in India: No Payoff, 20 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 389 (1998). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol20/iss2/5 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORRUPT PRACTICES IN INDIA: No PAYOFF I. INTRODUCTION Foreign investors constantly seek new business locations to increase profits and decrease expenses. With one of the fastest growing economies in the world, India is a popular site for foreign investment. 1 India, however, suffers from a major problem which threatens U.S. investment-corruption. A Gallup survey conducted throughout India reported that corruption is one of the most serious problems plaguing the country. 2 India's current anti- corruption laws are ineffective; hence, U.S. corporations find it increasingly difficult to follow the requirements of the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) while doing business in '3 India, "one of the most corrupt countries in the world." This comment analyzes the FCPA and its relationship to foreign investment in India. -

91 Adarsh Co-Operative Housing Society, Mumbai

91 ADARSH CO-OPERATIVE HOUSING SOCIETY, MUMBAI MINISTRY OF DEFENCE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 2013-2014 NINETY-FIRST REPORT FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI NINETY-FIRST REPORT PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2013-2014) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) ADARSH CO-OPERATIVE HOUSING SOCIETY, MUMBAI MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Presented to Lok Sabha on 9 December, 2013 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 9 December, 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI December, 2013/Agrahayana, 1935 (Saka) PAC No. 2018 Price: ` 143.00 © 2014 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition) and printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi-110 002. CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC A CCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2013-14) . (iii) COMPOSITION OF THE P UBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2012-13) . (v) COMPOSITION OF THE PUBLIC A CCOUNTS COMMITTEE (2011-12) . (vii) INTRODUCTION . (ix) REPORT PART I I. Introductory . 1 II. Denial of Records to Audit . 2 III. Genesis of the Land Sought by ACHS and its Physical Survey and Inspection . 3 IV. Possession of the Land by Army . 4 V. Issue of NOC . 12 VI. Khukri Eco Park . 15 VII. Objectives of the Society . 16 VIII. Membership of the Society and its Expansion . 18 IX. Concessions Granted by the Government of Maharashtra . 19 X. Modification of the MMRDA Development Plan for the Area to Accommodate the Society . 20 XI. Grant of Additional Floor Space Index . 21 XII. Further Relaxation to Grant Additional FSI in lieu of Recreation Ground . 23 XIII. Raising the Height of the Building Beyond Approval . -

Higher Education Summit 2012 ‘Improving Quality of Higher Education to Drive Goa’S Economy’ 0900 Hrs : 14 December 2012 : Tango Hall - Vivanta by Taj – Panaji Goa

Government of Goa Associate Partner Higher Education Summit 2012 ‘Improving Quality of Higher Education to drive Goa’s Economy’ 0900 hrs : 14 December 2012 : Tango Hall - Vivanta by Taj – Panaji Goa FINAL PROGRAMME Goa is a small state with high literacy and GDP of near 3500$. The economy is however in the primary and value add stage, be it in manufacture or services sector. The younger generation, nearly 22000 who enter the job market each year, aspire for well paying jobs and these are not easily available in the state today. The problems faced by Primary activities such as mining are troubling the state economy. The solution is to train our students to be eligible for more than Rs. 2.0 lakhs p.a. jobs and attract better industries that use them to make Products, lead Research and Development and Innovation. It is these sectors that will meet the aspiration of our young generation and also meet with approval from the Goan people at large. Goa needs to move beyond ~50% graduate enrollment to skill them better as in OECD countries to help drive our economy to higher added value. To move our higher education system to this path, CII has organized the Summit as we believe that Goa has to offer better quality learning to the students, to keep progressing sustainably. 1000 Hrs Inaugural Session 0900 Hrs Registration 0945 Hrs Delegates to be seated 0955 Hrs Arrival of the Honorable Chief Minister, Government of Goa 0957 Hrs Arrival of His Excellency, Governor of Goa 0959 Hrs Playing of the National Anthem 1000 Hrs Welcome Address Mr. -

Mahead-Dec2019.Pdf

MAHAPARINIRVAN DAY 550TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY: GURU NANAK DEV CLIMATE CHANGE VS AGRICULTURE VOL.8 ISSUE 11 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2019 ` 50 PAGES 52 Prosperous Maharashtra Our Vision Pahawa Vitthal A Warkari couple wishes Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray after taking oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. (Pahawa Vitthal is a pictorial book by Uddhav Thackeray depicting the culture and rural life of Maharashtra.) CONTENTS What’s Inside 06 THIS IS THE MOMENT The evening of the 28th November 2019 will be long remem- bered as a special evening in the history of Shivaji Park of Mumbai. The ground had witnessed many historic moments in the past with people thronging to listen to Shiv Sena Pramukh, Late Balasaheb Thackeray, and Udhhav Thackeray. This time, when Uddhav Thackeray took the oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra on this very ground, the entire place was once again charged with enthusiasm and emotions, with fulfilment seen in every gleaming eye and ecstasy on every face. Maharashtra Ahead brings you special articles on the new Chief Minister of Maharashtra, his journey as a politi- cian, the new Ministers, the State Government's roadmap to building New Maharashtra, and the newly elected members of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly. 44 36 MAHARASHTRA TOURISM IMPRESSES THE BEACON OF LONDON KNOWLEDGE Maharashtra Tourism participated in the recent Bharat Ratna World Travel Market exhibition in London. A Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar platform to meet the world, the event helped believed that books the Department reach out to tourists and brought meaning to life. tourism-related professionals and inform them He had to suffer and about the tourism attractions and facilities the overcome acute sorrow State has. -

Aphtha Crackers, HOPE and Polypropylene (D) If So, the Details Thereof; and .':Trojects Have Since Been Received by the C.;Ompany

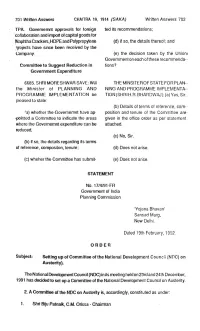

701 Written Answers CHAITRA 19, 1914 (SAKA) Written Answers 702 TPA. Govememnt approvals for foreign ted its recommendations; , collaboration and import of capital goods for ~aphtha Crackers, HOPE and Polypropylene (d) if so, the details thereof; and .':trojects have since been received by the c.;ompany. (e) the decision taken by the Union Govemment on each of these recommenda- Committee to Suggest Reduction in tions? Government Expenditure 6685. SHRI MORESHWAR SAVE: Will THE MINSITER OF STATE FOR PLAN- the Minister of PLANNING AND NING AND PROGRAMME IMPLEMENlA" PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTA TION be liON (SHRI H.R. BHARDWAJ): (a) Yes, Sir. pleased to state: (b) Details of terms of reference, com- 'a) whether the Govememnt have ap· pOSition and tenure of the Committee are -pointed a Committee to indicate the areas given in the office order as per statement where the Govememnt expenditure can be attached. reduced, (c) No, Sir. (b) if so, the details regarding its (erms of reference, compositon, tenure; (d) Does not arise. (c) wheher the Committee has submit- (e) Does not arise. STATEMENT No. 17/4/91-FR Government of India Planning Commission 'Yojana Shavan' Sansad Marg, New Delhi. Dated 19th February, 1992. ORDER Subject: Setting up of Committee ofthe National Development Council (NOC) on Austerity). The National Development Council (NOC) in its meeting held on 23rd and 24th December, 1991 has decided to set up a Convnittee of the National Development Council on Austerity. 2. A Convnittee of the NDC on Austerity is, accordingly, constituted as under: 1. Shri Biju Patnaik, C.M. Orissa - Chairman 703 Written Answers APRil 8, 1992 Written Answers 704 2. -

West Bengal Towards Change

West Bengal Towards Change Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Research Foundation Published By Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 Web :- www.spmrf.org, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone:011-23005850 Index 1. West Bengal: Towards Change 5 2. Implications of change in West Bengal 10 politics 3. BJP’s Strategy 12 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 14 Statements on West Bengal – excerpts 5. Statements of BJP National President 15 Amit Shah on West Bengal - excerpts 6. Corrupt Mamata Government 17 7. Anti-people Mamata government 28 8. Dictatorship of the Trinamool Congress 36 & Muzzling Dissent 9. Political Violence and Murder in West 40 Bengal 10. Trinamool Congress’s Undignified 49 Politics 11. Politics of Appeasement 52 12. Mamata Banerjee’s attack on India’s 59 federal structure 13. Benefits to West Bengal from Central 63 Government Schemes 14. West Bengal on the path of change 67 15. Select References 70 West Bengal: Towards Change West Bengal: Towards Change t is ironic that Bengal which was once one of the leading provinces of the country, radiating energy through its spiritual and cultural consciousness across India, is suffering today, caught in the grip Iof a vicious cycle of the politics of violence, appeasement and bad governance. Under Mamata Banerjee’s regime, unrest and distrust defines and dominates the atmosphere in the state. There is a no sphere, be it political, social or religious which is today free from violence and instability. It is well known that from this very land of Bengal, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore had given the message of peace and unity to the whole world by establishing Visva Bharati at Santiniketan. -

Enhancing the Effectiveness of Anti-Corruption Agencies

COMBATING ASIAN CORRUPTION: ENHANCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF ANTI-CORRUPTION AGENCIES Jon S.T. Quah* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 2 II. THE POLICY CONTEXTS OF ASIAN COUNTRIES ................ 8 A. Geographical Constraints ...................................................... I 0 B. Colonial Legacy .................................................................... 12 C. Economic Development ........................................................ 18 D. Population and Culture ......................................................... 20 E. Political and Legal Systems .................................................. 22 F. Difficult Governance Environment of Fragile States ........... 24 III. COMBATING CORRUPTION WITH A SINGLE ANTI- CORRUPTION AGENCY (ACA) .............................................. 26 A. Singapore's Effective Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau ( CPI B) ...................................................................... 26 B. Hong Kong's Effective Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) .................................................. 31 C. South Korea's "Toothless" ACAs ........................................ 35 IV. COMBATING CORRUPTION WITH MANY ANTI- CORRUPTION AGENCIES ....................................................... 41 A. China's Flawed A CAs .......................................................... 42 I. Reliance on Multiple A CAs ............................................. 43 2. Reliance on Anti-Corruption -

Studies of the Effect of Democracy on Corruption

Studies of the Effect of Democracy on Corruption Shrabani Saha and Neil Campbell Department of Applied and International Economics Massey University, Palmerston North New Zealand Corresponding author: Shrabani Saha Email: [email protected] Phone: 64 (6) 350 5999 Extn. 2663 Fax: 64 (6) 350 5660 Prepared for the 36th Australian Conference of Economists ‘Economics of Corruption Session’ Tasmania, Australia, 24-26 September, 2007 Draft: Please do not cite without authors’ permission. 1 Abstract This paper studies the influence of democracy on the level of corruption. In particular, does democracy necessarily reduce a country’s level of corruption? The growing consensus reveals that there is an inverse correlation between democracy and corruption; the more democracy and the less corruption. This study argues that a simple ‘electoral democracy’ is not sufficient to reduce corruption. The role of sound democratic institutions, including an independent judiciary and an independent media along with active political participation is crucial to combat corruption. To illustrate the ideas, this study develops a simple model that focuses on the role of democratic institutions, where it assumes that the detection technology is a function of democracy. Under this assumption, the active and effective institutions lead to careful monitoring of agents, which increases the probability of detection and punishment of corrupt activities and reduces the level of corruption. Keywords: Corruption; Bribery; Democracy; Development JEL classification: D73; K42 2 1. Introduction Corruption is viewed as one of the most severe bottlenecks in the process of economic development and in modernizing a country particularly in developing countries. Recent empirical research on the consequences of corruption confirms that there is a negative relationship between corruption and economic growth. -

Page-1.Qxd (Page 3)

MONDAY, JUNE 9, 2014 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 Mumbai Metro rolls out, over 1 New package for rehabilitation Govt may not hike plan outlay 3 cops among 7 killed, 22 injured in accidents social sector schemes such as mates of the Rs 5,55,532 crore, vehicle and it plunged into Govt Medical College Hospital lakh commuters take maiden ride of Kashmiri Pandits in offing Bharat Nirman, rural employ- for keeping a tab on the fiscal gorge. Jammu. MUMBAI, June 8: carrying around 11 lakh passen- for its approval. following militant activities has ment guarantee and National deficit. This was second year in On getting information, police The deceased were identified gers. Every coach can carry 375 Sources said soon after tak- increased by six-seven lakhs. Rural Health Mission. a row when UPA Government team from Udhampur Police as Ronika Rajput (22), daughter After a long wait, the first passengers, while the entire train ing over as Prime Minister, Like the previous one, "In present economic sce- cut Plan spending substantially Station led by SHO Mahesh of Jung Bahadur, resident of Metro service in the bustling can transport 1,500 commuters. Narendra Modi had sought returnee migrant families will nario, the new Government may to keep fiscal deficit under con- Sharma rushed to the spot and Bhagwati Nagar, Jammu and metropolis was rolled out today The introduction of Metro detailed information from be provided transit accommoda- not go for substantial increase in trol. started rescue operation. The Rohit Kumar (25), son of Mahesh with the Chief Minister services will revolutionise the Union Home Ministry about the tion during the interim period the Plan expenditure over what According to the latest locals also joined. -

In the High Court of Delhi at New Delhi

WWW.LIVELAW.IN IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI % Judgment delivered on: 22.05.2020 + CRL.A. 1186/2017 MADHU KODA .....Appellant versus STATE THROUGH CBI ..... Respondent Advocates who appeared in this case: For the Appellant :Mr Abhimanyu Bhandari, Ms Gauri Rishi, Ms Srishti Juneja, Ms Aashima Singhal and Mr Vinay Prakash, Advocates. For the Respondent :Mr R. S. Cheema, Sr. Advocate (SPP) with Ms Tarannum Cheema, Ms Smrithi Suresh, Ms Hiral Gupta and Mr Akshay Nayarajan, Advocates. CORAM HON’BLE MR JUSTICE VIBHU BAKHRU JUDGMENT VIBHU BAKHRU, J CRL.M.(BAIL) 2273/2017 & CRL.M.A. 38740/2019 1. The appellant has filed the present applications, inter alia, praying that the operation of the impugned order dated 13.12.2017 passed by the learned Special Judge convicting the appellant of the offence of criminal misconduct under sub-clauses (ii) and (iii) of clause (d) of sub-section (1) of section 13 read with sub-section (2) of section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (hereafter ‘PC Act’), be stayed. CRL.A. 1186/2017 Page 1 of 35 WWW.LIVELAW.IN 2. The appellant desires to contest for election to public offices, including contest elections for the Legislative Assembly of the State of Jharkhand but is disqualified to do so on account of his conviction. The appellant states that he was elected as a member of Bihar Legislative Assembly for the first time in the year 2000. On 15.11.2000, the State of Jharkhand was carved out from the erstwhile State of Bihar. The appellant held the office of the Minister of the State for Rural Engineering Organization thereafter and continued to do so till the year 2003. -

Civil) No 494 of 2012 Justice Ks Puttaswamy (Retd

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO 494 OF 2012 JUSTICE K S PUTTASWAMY (RETD) & ANR ...PETITIONERS Versus UNION OF INDIA & ORS ...RESPONDENTS WITH T C (C) NO 151 OF 2013 T C (C) NO 152 OF 2013 W P (C) NO 833 OF 2013 W P (C) NO 829 OF 2013 T P (C) NO 1797 OF 2013 W P (C) NO 932 OF 2013 1 T P (C) NO 1796 OF 2013 CONMT. PET. (C) NO 144 OF 2014 T P (C) NO 313 OF 2014 T P (C) NO 312 OF 2014 SLP (CRL) NO 2524 OF 2014 W P (C) NO 37 OF 2015 W P (C) NO 220 OF 2015 CONMT. PET. (C) NO 674 OF 2015 in W P (C) NO 829 OF 2013 T P (C) NO 921 OF 2015 CONMT. PET. (C) NO 470 OF 2015 W P (C) NO 231 OF 2016 CONMT. PET. (C) NO 444 OF 2016 CONMT. PET. (C) NO 608 OF 2016 W P (C) NO 797 OF 2016 CONMT. PET. (C) NO 844 OF 2017 2 W P (C) NO 342 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 372 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 841 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 1058 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 966 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 1014 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 1002 OF 2017 W P (C) NO 1056 OF 2017 AND WITH CONMT. PET. (C) NO 34 OF 2018 in W P (C) NO 1014 OF 2017 3 J U D G M E N T INDEX A Introduction: technology, governance and freedom B The Puttaswamy1 principles B.I Origins: privacy as a natural right B.2 Privacy as a constitutionally protected right : liberty and dignity B.3 Contours of privacy B.4 Informational privacy B.5 Restricting the right to privacy B.6 Legitimate state interests C Submissions C.I Petitioners’ submissions C.2 Respondents’ submissions D Architecture of Aadhaar: analysis of the legal framework E Passage of Aadhaar Act as a Money Bill E.I Judicial Review of the Speaker’s Decision E.2 Aadhaar Act as a Money Bill F Biometrics, Privacy and Aadhaar F.I Increased use of biometric technology F.2 Consent in the collection of biometric data F.3 Position before the Aadhaar legislation 1 (2017) 10 SCC 1 4 F.4 Privacy Concerns in the Aadhaar Act 1.