Insurgency, Counter-Insurgency, and Democracy in Central India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krishna HO Sites.Xlsx

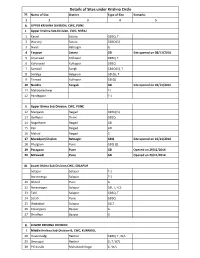

Details of Sites under Krishna Circle SL. Name of Site District Type of Site Remarks 12 3 4 5 A. UPPER KRISHNA DIVISION, CWC, PUNE I. Upper Krishna Sub‐Division, CWC, MIRAJ 1 Karad Satara GDSQ, T 2 Warunji Satara GDSQ (S) 3 Nivali Ratnagiri G 4 Targaon Satara GD Site opened on 08/11/2016 5 Arjunwad Kolhapur GDSQ, T 6 Kurunwad Kolhapur GDSQ 7 Samdoli Sangli GDSQ (S), T 8 Sadalga Belgaum GD (S), T 9 Terwad Kolhapur GD (S) 10 Nandre Sangali GD Site opened on 03/11/2016 11 Mahabaleshwar T‐I 12 Pandegaon T‐1 II. Upper Bhima Sub Division, CWC, PUNE 12 Mangaon Raigad GDSQ( S) 13 Badlapur Thane GDSQ 14 Nagathone Raigad GD 15 Pen Raigad GD 16 Mahad Raigad G 17 Muradpur/Chiplun Ratnagiri GDQ Site opened on 10/11/2016 18 Phulgaon Pune GDQ (S) 19 Paragaon Pune GD Opened on 29/11/2014 20 Mirawadi Pune GD Opened on 29/11/2014 III. Lower Bhima Sub Division,CWC, SOLAPUR Solapur Solapur T‐1 Boriomerga Solapur T‐1 21 Dhond Pune G 22 Narasingpur Solapur GD, T, FCS 23 Takli Solapur GDSQ, T 24 Sarati Pune GDSQ 25 Wadakbal Solapur GD,T 26 Kokangaon Bijapur G 27 Shirdhon Bijapur G B. LOWER KRISHNA DIVISION I Middle Krishna Sub‐Division‐II, CWC, KURNOOL 28 Huvenhedgi Raichur GDSQ, T, W/L 29 Deosugur Raichur G, T, W/L 30 P D Jurala Mahaboob Nagar G, W/L 31 K Agraharam Mahaboob Nagar G, T, W/L 32 Yadgir Yadgir GDSQ, T, W/L 33 Malkhed Gulbarga GDSQ, T 34 Jewangi Ranga Reddy G, T 35 Suddakallu Mahaboob Nagar GDSQ, T Opened on 20/11/2014 II. -

“Being Neutral Is Our Biggest Crime”

India “Being Neutral HUMAN RIGHTS is Our Biggest Crime” WATCH Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-356-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-356-0 “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Maps........................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary/ Abbreviations ..........................................................................................3 I. Summary.............................................................................................................5 Government and Salwa Judum abuses ................................................................7 Abuses by Naxalites..........................................................................................10 Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability.................. -

Bastar, Maoism and Salwa Judum.” in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XLI 29, July 22, 2006, Pp

Bastar, Maoism and Salwa Judum.” In Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XLI 29, July 22, 2006, pp. 3187-3192 Bastar, Maoism and Salwa Judum Nandini Sundar1 Visitors to the official Bastar website (www.bastar.nic.in) will ‘discover’ that Gonds “have pro- fertility mentality”, that “marriages...between brothers and sisters are common,” and that “the Murias prefer 'Mahua' drinks rather than medicines for their ailments.” “The tribals of this area”, says the website, “is famous for their 'Ghotuls' where the prospective couples do the 'dating' and have free sex also.” As for the Abhuj Marias, “(t)hese people are not cleanly in their habits, and even when a Maria does bathe he does not wash his solitary garments but leaves it on the bank. When drinking from a stream they do not take up water in their hands but put their mouth down to it like cattle.” Some of the tribals are “leading a savage life”, we are told, “they do not like to come to the outer world and mingle with the modern civilisation.” Into this charming picture of ‘savages’ who ‘shoot down strangers with arrows’, one must unfortunately bring in a few uncomfortable facts. What used to be the former undivided district of Bastar (since 2001 carved into the districts of Dantewada, Bastar and Kanker) is currently a war zone. The main roads, in Dantewada in particular, but also in parts of Bastar and Kanker, are full of CRPF and other security personnel, out on combing operations.2 The Maoists control the jungles. In the frontlines of this battle are ordinary villagers who are being pitted against each other on a scale unparalleled in the history of Indian counterinsurgency. -

India's Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 22 India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency by Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Hard-line communists, belonging to the political group Naxalite, pose with bows and arrows during protest rally in eastern Indian city of Calcutta December 15, 2004. More than 5,000 Naxalites from across the country, including the Maoist Communist Centre and the Peoples War, took part in a rally to protest against the government’s economic policies (REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw) India’s Naxalite Insurgency India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency By Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. -

Malkangiri District, Orissa

Govt. of India MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MALKANGIRI DISTRICT, ORISSA South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar March, 2013 MALKANGIRI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl ITEMS Statistics No 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) 5791 ii. Administrative Divisions as on 31.03.2007 Number of Tehsil / Block 3 Tehsils, 7 Blocks Number of Panchayat / Villages 108 Panchayats 928 Villages iii Population (As on 2011 Census) 612,727 iv Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1437.47 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Hills, Intermontane Valleys, Pediment - Inselberg complex and Bazada Major Drainages Kolab, Potteru, Sileru 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest Area 1,430.02 b) Net Sown Area 1,158.86 c) Cultivable Area 1,311.71 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Ultisols, Alfisols 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROP Pulses etc. : 91,871 Ha 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) Dugwells 2,033 Ha Tube wells / Borewells Tanks / ponds 1,310 Ha Canals 71,150 Ha Other sources - Net irrigated area 74,493 Ha Gross irrigated area 74,493 Ha 7. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB( As on 31-3-2011) No of Dugwells 29 No of Piezometers 4 10. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS Granites, Granite Gneiss, Granulites & its variants, Basic intrusives 11. HYDROGEOLOGY Major Water bearing formation Granites, Granite Gneiss Pre-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 2.37 – 9.02 Post-monsoon Depth to water level during 2011 0.45 – 4.64 Long term water level trend in 10 yrs (2001-2011) in m/yr Mostly rise: 0.034 – 0.304(59%) Some Fall : 0.010 – 0.193(41%) 12. -

Page-1.Qxd (Page 3)

MONDAY, JUNE 9, 2014 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 Mumbai Metro rolls out, over 1 New package for rehabilitation Govt may not hike plan outlay 3 cops among 7 killed, 22 injured in accidents social sector schemes such as mates of the Rs 5,55,532 crore, vehicle and it plunged into Govt Medical College Hospital lakh commuters take maiden ride of Kashmiri Pandits in offing Bharat Nirman, rural employ- for keeping a tab on the fiscal gorge. Jammu. MUMBAI, June 8: carrying around 11 lakh passen- for its approval. following militant activities has ment guarantee and National deficit. This was second year in On getting information, police The deceased were identified gers. Every coach can carry 375 Sources said soon after tak- increased by six-seven lakhs. Rural Health Mission. a row when UPA Government team from Udhampur Police as Ronika Rajput (22), daughter After a long wait, the first passengers, while the entire train ing over as Prime Minister, Like the previous one, "In present economic sce- cut Plan spending substantially Station led by SHO Mahesh of Jung Bahadur, resident of Metro service in the bustling can transport 1,500 commuters. Narendra Modi had sought returnee migrant families will nario, the new Government may to keep fiscal deficit under con- Sharma rushed to the spot and Bhagwati Nagar, Jammu and metropolis was rolled out today The introduction of Metro detailed information from be provided transit accommoda- not go for substantial increase in trol. started rescue operation. The Rohit Kumar (25), son of Mahesh with the Chief Minister services will revolutionise the Union Home Ministry about the tion during the interim period the Plan expenditure over what According to the latest locals also joined. -

The Ion N) .$S S Is Are on Ed Ces Ive Ve Nd Ion T Is of an Ng to Ip. Ing Ing Cal an an Nd Is Nd * +DUDJRSDO This Note Is an Ac

Vol. 8(1) Socio-Legal Review 2012 The second one is establishing RHRIs at the sub-regional level through the THE M AOIST M OVEMENT AND active cooperation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation THE INDIAN S TATE : M EDIATING PEACE (SAARC) in South Asia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) LQ6RXWK(DVW$VLDDQGWKH3DFLÀF,VODQGV)RUXP 3,) LQWKH3DFLÀFUHJLRQ$V *+DUDJRSDO a starting point, the establishment of sub-regional human rights mechanisms is important for the protection of human rights in the region, and once there are This note is an account of the mediation/ negotiation at two separate sub-regional arrangements, they can work toward a human rights institution on kidnapping incidents- in Gurtendu in Andhra Pradesh in 1987 and the regional level. in Malkangiri in Orissa in February 2011 (in which the author was SHUVRQDOO\LQYROYHG ,WH[DPLQHVWKHUHVSRQVHRI WKH6WDWHWKHHQVXLQJ The third one is strengthening the role of the APF. The APF was established SHDFHWDONVDQGDQDO\]HVZKHWKHUDQ\GHPRFUDWLFVSDFHVZHUHRSHQHGXS to enhance the capacity of member NHRIs for better human rights practices consequently. at the national level and astrengthened domestic environment for effective implementation of international human rights standards. It will ultimately move I. BRIEF BACKGROUND AND H ISTORY OF THE NAXALITE M OVEMENT .............114 governments to establish RHRIs in the region. The development of the APF and its network of member NHRIs will also mobilize civil societies across the region 1. The Origin of the Movement ....................................................................114 to reach regional consensus for establishing RHRIs and the recognition that it is 2. The Politics of the State’s Response .........................................................115 necessary to have a regional human rights protection system. -

In the High Court of Delhi at New Delhi

WWW.LIVELAW.IN IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI % Judgment delivered on: 22.05.2020 + CRL.A. 1186/2017 MADHU KODA .....Appellant versus STATE THROUGH CBI ..... Respondent Advocates who appeared in this case: For the Appellant :Mr Abhimanyu Bhandari, Ms Gauri Rishi, Ms Srishti Juneja, Ms Aashima Singhal and Mr Vinay Prakash, Advocates. For the Respondent :Mr R. S. Cheema, Sr. Advocate (SPP) with Ms Tarannum Cheema, Ms Smrithi Suresh, Ms Hiral Gupta and Mr Akshay Nayarajan, Advocates. CORAM HON’BLE MR JUSTICE VIBHU BAKHRU JUDGMENT VIBHU BAKHRU, J CRL.M.(BAIL) 2273/2017 & CRL.M.A. 38740/2019 1. The appellant has filed the present applications, inter alia, praying that the operation of the impugned order dated 13.12.2017 passed by the learned Special Judge convicting the appellant of the offence of criminal misconduct under sub-clauses (ii) and (iii) of clause (d) of sub-section (1) of section 13 read with sub-section (2) of section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (hereafter ‘PC Act’), be stayed. CRL.A. 1186/2017 Page 1 of 35 WWW.LIVELAW.IN 2. The appellant desires to contest for election to public offices, including contest elections for the Legislative Assembly of the State of Jharkhand but is disqualified to do so on account of his conviction. The appellant states that he was elected as a member of Bihar Legislative Assembly for the first time in the year 2000. On 15.11.2000, the State of Jharkhand was carved out from the erstwhile State of Bihar. The appellant held the office of the Minister of the State for Rural Engineering Organization thereafter and continued to do so till the year 2003. -

FEBRUARY 2017 Rs

Vol. XXXVII, No. 2 ISSN-0970-8693 FEBRUARY 2017 Rs. 20 Editorial : Simultaneous Parliament and State Assembly Elections Simultaneous Parliament and State Not Possible and Against Federalism Assembly Elections - Rajindar Sachar (1) Rajindar Sachar ARTICLES, REPORTS & DOCUMENTS: Prime Minister Modi has for last 6 months kept a continuous refrain for Is the human rights protection regime in India crumbling? - Pushkar Raj (2); Analysis: holding simultaneously Lok Sabha and State Assembly polls and the Sachar Report Gathers Dust, Abolishing supposed advantages that would flow from it. As was to be expected Personal Laws can't Change Dark Realities - number of newspapers and persons are picking up this matter. It is Humra Quraishi (11); Resolution: (Adopted in unfortunate that Election Commission of India and Nite Aayog should the seminar on 'Justice Sachar Committee Report: A Review After 10 Years') (13); PUCL have gone along with this suggestion without even the minimum TN & Pud. State Report read out in the PUCL constitutional requirement of a public debate and Seminars – and more National Convention at Raipur: Appraisal unforgivably without discussions of the matter with other major political Report on the activities carried out during parties and the State governments. In order to have a worthwhile debate, 2014-16 (17). it is necessary to know the legal and factual situation at present. The present life of Lok Sabha expires in May 2019. Modis repeated PRESS STATEMENTS, LETTERS, AND NEWS: emphasis on simultaneous poll is actuated by the realization that the Press Release: NHRC finds 16 women prima mood of exhilaration that he was able to create in 2014 Parliamentary poll facie victims of rape, sexual and physical assault by police personnel in Chhattisgarh is diminishing very fast. -

Worldwide Attacks Against Dams

Worldwide Attacks Against Dams A Historical Threat Resource for Owners and Operators 2012 i ii Preface This product is a compilation of information related to incidents that occurred at dams or related infrastructure world-wide. The information was gathered using domestic and foreign open-source resources as well as other relevant analytical products and databases. This document presents a summary of real-world events associated with physical attacks on dams, hydroelectric generation facilities and other related infrastructure between 2001 and 2011. By providing an historical perspective and describing previous attacks, this product provides the reader with a deeper and broader understanding of potential adversarial actions against dams and related infrastructure, thus enhancing the ability of Dams Sector-Specific Agency (SSA) partners to identify, prepare, and protect against potential threats. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) National Protection and Programs Directorate’s Office of Infrastructure Protection (NPPD/IP),which serves as the Dams Sector- Specific Agency (SSA), acknowledges the following members of the Dams Sector Threat Analysis Task Group who reviewed and provided input for this document: Jeff Millenor – Bonneville Power Authority John Albert – Dominion Power Eric Martinson – Lower Colorado River Authority Richard Deriso – Federal Bureau of Investigation Larry Hamilton – Federal Bureau of Investigation Marc Plante – Federal Bureau of Investigation Michael Strong – Federal Bureau of Investigation Keith Winter – Federal Bureau of Investigation Linne Willis – Federal Bureau of Investigation Frank Calcagno – Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Robert Parker – Tennessee Valley Authority Michael Bowen – U.S. Department of Homeland Security, NPPD/IP Cassie Gaeto – U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Intelligence and Analysis Mark Calkins – U.S. -

Inter State Agreements

ORISSA STATE WATER PLAN 2 0 0 4 INTER STATE AGGREMENTS Orissa State Water Plan 9 INTER STATE AGREEMENTS Orissa State has inter state agreements with neighboring states of West Bengal, Jharkhand ( formerly Bihar),Chattisgarh (Formerly Madhya Pradesh) and Andhra Pradesh on Planning & Execution of Irrigation Projects. The Basin wise details of such Projects are briefly discussed below:- (i) Mahanadi Basin: Hirakud Dam Project: Hirakud Dam was completed in the year 1957 by Government of India and there was no bipartite agreement between Government of Orissa and Government of M.P. at that point of time. However the issues concerning the interest of both the states are discussed in various meetings:- Minutes of the meeting of Madhya Pradesh and ORISSA officers of Irrigation & Electricity Departments held at Pachmarhi on 15.6.73. IBB DIVERSION SCHEME: 3. Secretary, Irrigation & Power, Orissa pointed out that Madhya Pradesh is constructing a diversion weir on Ib river. This river is a source of water supply to the Orient Paper Mill at Brajrajnagar as well as to Sundergarh, a District town in Orissa State. Government of Orissa apprehends that the summer flows in Ib river will get reduced at the above two places due to diversion in Madhya Pradesh. Madhya Pradesh Officers explained that this work was taken up as a scarcity work in 1966- 77 and it is tapping a catchment of 174 Sq. miles only in Madhya Pradesh. There is no live storage and Orissa should have no apprehensions as regards the availability of flows at the aforesaid two places. It was decided that the flow data as maintained by Madhya Pradesh at the Ib weir site and by Orissa at Brajrajnagar and Sundergarh should be exchanged and studied. -

Police Medal for Meritorious Service Republic

POLICE MEDAL FOR MERITORIOUS SERVICE REPUBLIC DAY-2016 ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SHRI POCHINENI RAMESHAIAH, SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, REGIONAL VIGILANCE & ENFORCEMENT, NELLORE, ANDHRA PRADESH 2. SHRI B SRINIVAS, ADDITIONAL SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE INTELLIGENCE SECURITY WING, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 3. SHRI S RAJASEKHAR RAO, ADDITIONAL SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, REGIONAL VIGILANCE & ENFORCEMENT OFFICE, TIRUPATI, ANDHRA PRADESH 4. SHRI V. VIJAYA BHASKAR, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, INTELLIGENCE, HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH 5. SHRI NUNNABODI SATYANANDAM, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, REGIONAL OFFICE, CID, VIJAYAWADA CITY, ANDHRA PRADESH 6. SHRI CHINTADA LAKSHMIPATHI, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, ANTI CORRUPTION BUREAU, VIZIANAGARAM, ANDHRA PRADESH 7. SHRI N SUBBA RAO, DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, ANANTAPURAMU DISTRICT (AP), ANDHRA PRADESH 8. SHRI KINJARAPU PRABHAKAR, ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER OF POLICE, TRAFFIC, VISAKHAPATNAM, ANDHRA PRADESH 9. SHRI RAJAPU RAMANA, ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER OF POLICE, EAST SUB-DIVISION, VISAKHAPATNAM, ANDHRA PRADESH 10. SHRI SUDHABATHULA RAMESH BABU, SUB INSPECTOR, WEST GODAVARI DISTRICT (AP), ANDHRA PRADESH 11. SHRI SHAIK SHAFI AHMED, SUB INSPECTOR OF POLICE, DSB, NELLORE (AP), ANDHRA PRADESH 12. SHRI B. LAKSHMAIAH, ARMED RESERVE SUB INSPECTOR, PTC, TIRUPATI (AP), ANDHRA PRADESH 13. SHRI SABBASANI RANGA REDDY, HEAD CONSTABLE, 6TH BN APSP, MANGALAGIRI GUNTUR (AP), ANDHRA PRADESH 14. SHRI AGRAHARAM SREENIVASA SHARMA, HEAD CONSTABLE, KADAPA-II TOWN P.S., ANDHRA PRADESH 1 15. SHRI J. NAGESWARA RAO, ARMED RESERVE HEAD CONSTABLE, CAR, VIJAYAWADA (AP), ANDHRA PRADESH ASSAM 16. SMT. INDRANI BARUAH, SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KAMRUP, ASSAM 17. SHRI DHARANI DHAR MAHANTA, INSPECTOR OF POLICE S.B. ORGANIZATION, KAHILIPARA, GUWAHATI, ASSAM 18. SHRI TAPAN KUMAR MAHANTA, SUB INSPECTOR OF POLICE (AB), POLICE COMMISSIONERATE GUWAHATI, ASSAM 19. SHRI PANNE LAL GUPTA, ASSISTANT SUB INSPECTOR OF POLICE (BORDER HQ), SRIMANTAPUR GUWAHATI, ASSAM 20.