Determination in Merger Notification M/08/011 – Heineken/Scottish & Newcastle ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heineken Uk Star Pubs & Bars Pricing Schedule 22.01.2018

Heineken Uk Star Pubs & Bars Pricing Schedule 22.01.2018 Brewery SKU Brand description ABV Type / size No Case 20L 30L 40.9L 45.4L 50L 81.8L 100L 163.6L KEG ALES £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ Heineken AT23 JOHN SMITHS BITTER 3.6 KEG 136.93 448.17 Heineken AT21/AT22/AAH5 JOHN SMITHS EXTRA SMOOTH* 3.6 KEG 88.80 148.01 295.97 484.44 Heineken A854 MAGNET 4.0 KEG 139.81 457.60 Heineken A381 NEWCASTLE EXHIBITION 4.3 KEG 140.26 459.07 Heineken BS49 NEWCASTLE BROWN ALE 4.7 KEG 112.78 615.21 Heineken BS50 LAGUNITAS IPA 6.2 KEG 139.32 777.27 Heineken BS80 LAGUNITAS AUNT SALLY 5.7 KEG 144.74 807.50 Theakston BJ48 THEAKSTON BEST 3.8 KEG 146.60 479.82 Theakston A359 THEAKSTON MILD 3.5 KEG 128.23 419.70 Theakston BM61 THEAKSTON SMOOTH DARK 3.5 KEG 140.23 458.97 Heineken BS46 AFFLIGEM BLONDE 6.8 KEG 87.66 717.32 Theakstons BR64 THEAKSTON PECULIER IPA 5.1 KEG 126.87 692.08 Theakston BS23 THEAKSTON PECULIER PALE ALE 4.5 KEG 125.53 684.77 Heineken BS30 CALEY RARE RED RYE PALE ALE 4.3 KEG 127.70 696.60 Heineken BS57 MALTSMITHS AMERICAN IPA 4.6 KEG 126.16 688.20 PACKAGED ALES Heineken CJ26 CALEY DEUCHARS 4.4 500ML NRB 8 17.83 729.51 Heineken DN58 CALEY BILLS BEER 4.6 500ML NRB 8 17.99 736.06 Heineken CJ67 JS EXTRA SMOOTH 3.6 440ML CAN 20 43.86 679.74 Heineken D181 NEWCASTLE BROWN ALE 4.7 550ML NRB 12 24.29 602.32 Theakstons CJ19 THEAKSTON OLD PECULIER 5.6 500ML NRB 8 16.04 656.28 Theakstons CJ18 THEAKSTON XB 4.5 500ML NRB 8 16.11 659.14 Theakstons CJ36 THEAKSTON LIGHTFOOT 4.1 500ML NRB 8 16.18 662.00 Theakstons CM67 THEAKSTON PALE ALE 4.5 500ML NRB 8 16.11 659.14 Heineken -

Imported Beer Xingu

New Release Cabernet Sauvingnon • Moscato • White Zinfandel • Merlot Pinot Noir • Chardonnay • Riesling • Pinot Grigio Award Winning Enjoy Our Family’s Award Winning Tequilas Made from 100% Agave in the Highlands of Jalisco. www. 3amigostequila.com Please Drink Responsibly Amigos Visit AnchorBrewing.com for new releases! ANCB_AD_Hensley.indd 1 P i z z a P o r t 9/19/17 10:46 AM Brewing Company Carlsbad, CA | Est. 1987 Good Beer Brings Good Cheer Every Family has a Story. Welcome to Ours! 515144 515157 515147 515141 515142 515153 515150 515152 515140 Chateau Diana Winery: Family Owned and Operated. PRESCOT T BREWING COMPANY’S ORIGINAL PUB BREWHOUSE Established 1994 10 Hectolitre, three fermenters then, five now, 1500 barrels current annual capacity. PRESCOT T BREWING COMPANY’S PRODUCTION PLANT Established 2011 30 barrel brewhouse, 30, 60, and 90 barrel fermenters, 6,800 barrel annual capacity with room to grow. 130 W. Gurley Street, Prescott, AZ | 928.771.2795 | www.prescottbrewingcompany.com The Orange Drink America Loves! 100% Vitamin C • 60 calories per 8 oz. Available in 8 flavors • 16 oz. bottle © 2017 Sunny Delight Beverage Co. 8.375” x 5.44” with a .25 in. bleed Small Batch Big Fun World Class Kick Ass Rock & Roll Every Margarita in the ballpark Tequila! is poured with our Silver Tequila! Premium craft tequila ~ made in Mexico locally owned by roger clyne & The Peacemakers Jeremy Kosmicki Head Brewmaster Jason Heystek Lead Guitar/Barrel Maestro WE ARE FLAGSTAFF PROUDLY INDEPENDENT TABLE OF CONTENTS DOMESTIC BEER MODERN TIMES BEER .................................... 8 DAY OF THE DEAD ....................................... 12 10 BARREL BREWERY .................................... -

Beer Hunters Dry Packs Exclusiive

BEER HUNTERS DRY PACKS EXCLUSIIVE BREWS Exclusive Recipes 17 Golden Wheat Lager Goanna Special 4.80% Australia Exclusive $32.90 23 Scoሀsh Highlands Heavy Scoሀsh Ale 4.10% Belgium Exclusive $32.90 26 Canadian Brown Ale Canadian specialty 5.00% Canada Exclusive $32.90 49 Pancho Special Mexican Specialty 5.10% Mexico Exclusive $32.90 57 North Brown Ale Brown Ale 4.80% England Exclusive $32.90 64 Honey Lemon Fruit Style Beer 5.20% Australia Exclusive $32.90 80 Club Biᘀer English Biᘀer 3.90% England Exclusive $32.90 96 Canadian Creamy Ale Canadian style beer 4.80% Canada Exclusive $32.90 97 Canadian Creamy Porter Porter style beer 4.4‐4.8% Canada Exclusive $32.90 Scoሀsh Highlands 98 Export Scoሀsh ale style beer 4.50% Scotland Exclusive $32.90 Canadian speciality 100 Speciality Ale beer 4.90% Canada Exclusive $32.90 German Pilsner style 102 German Classic Pilsner beer 4.90% Germany Exclusive $32.90 103 Dark Wheat Dunkel Wheat style beer 4.70% Canada Exclusive $32.90 104 October Lager Octoberfestbier 5.20% Germany Exclusive $32.90 105 Munich Golden Munich pale ale style 4.90% Germany Exclusive $32.90 106 Bavarian Dark Bavarian Dark style 4.70% Germany Exclusive $32.90 107 Nut Brown Ale Brown Ale Style 4.30% USA Exclusive $32.90 108 Wheat Wheat style beer 4.80% Ireland Exclusive $32.90 109 Strong Biᘀer English biᘀer style 4.80% England Exclusive $32.90 112 Plzen Classic Pilsner 4.70% Czech Exclusive $32.90 120 Raj Pale Ale Indian Pale Ale 5.60% Czech Exclusive $32.90 147 Munich Helles Munich pale 4.90% Germany Exclusive $32.90 153 Scoሀsh Heavy -

The Role of Geology in the Fall and Rise of Local Brewing Alex Maltman Abstract

The role of geology in the fall and rise of local brewing Alex Maltman Abstract. Beer has an ancient heritage and brewing was almost ubiquitous by the Middle Ages in the British Isles. It later became progressively more regional. The East Midlands had good waters, and barley from both the sandy soils on the Sherwood Sandstone and the fertile, clayey soils on the Lower Jurassic of the Vale of Belvoir. Hops were grown in the heavy soils on Mercia Mudstone of the ‘North Clays’ district, and Nottingham’s sandstone caves provided ideal storage conditions for the beer. Subsequently the water, especially at Burton upon Trent, proved ideal for the newly fashionable pale ale or bitter. Gypsiferous Triassic aquifers gave the water a perfect ionic balance for this style of beer. Moreover, the calcium sulphate allowed high hopping rates, and hence the development of the Export and India Pale Ale styles, now of international fame. By the 20th century, brewing science had showed how Burton waters could be emulated elsewhere, and the brewing industry became highly commercialised and centralised. The craft beer movement is now heralding a return to local values, including the importance of local ingredients, some of which show a geological influence. Beer is often seen as the simple quaffing drink of the beer for sale (Unger, 2005). Beer was drunk with every masses, a contrast with the sophistication of wine. In meal: the consumption was something like two pints fact, in many ways beer is the more complex drink of every day, per person. Incidentally, the brewing was the two. -

Wine, Beer & Food

12TH ANNUAL Grand Rapids INTERNATIONAL Wine, Beer & Food FESTIVAL DeVos Place NOVEMBER 21-23, 2019 NOV 21-23 THE WINE, BEER & FOOD FESTIVAL IS PRODUCED BY WINE & FOOD FESTIVAL, LLC Red, White and all the blue you could ever need VISIT OUR BOOTH It’s where everything just comes together. Where you’re free to show your true colors. And where you can’t help but feel like you’re in a pre y great place right now. TraverseCity.com Red, White and all the blue you could ever need VISIT OUR BOOTH It’s where everything just comes together. Where you’re free to show your true colors. And where you can’t help but feel like you’re in a pre y great place right now. TraverseCity.com OFFICIAL WINE, BEER & FOOD FESTIVAL PROGRAM FOOD STAGE SPONSOR & RENDEZBREW SPONSOR Welcome to the 12th Annual Grand Rapids International Wine, Beer & Food Festival! ELITE COLLECTION SPONSOR ine & Food Festival, LLC and the Convention and Arena Authority have once again paired up to produce the largest event of its kind in the Midwest…a festival BEER CITY STATION SPONSOR just this year named one of the “Best Fall Wine Festivals In North America MAJOR FEATURE SPONSOR You Don’t Want To Miss” --Forbes.com Sept. 15, 2019 TASTING TICKET SPONSOR This year’s event once again is a celebration for your palate… • The Vineyard in the Steelcase Ballroom featuring 1,200+ wines including the “Elite PAIRINGS SPONSOR Collection” offering the finest wines at the Festival, along with expert assistance from the directors of Tasters Guild International; • Beer City Station & Cider Hall in Hall -

Draft Beer Craft

DRAFT BEER DOMESTIC / IMPORT COORS LIGHT BUD LIGHT DOS EQUIS AMBAR CRAFT CABIN FEVER BROWN ALE New Holland Brewing Co. // Holland, MI, USA| ABV 6.5% | IBU 25 FAT TIRE AMBER ALE New Belgium Brewing Co. // Fort Collins, CO, USA | ABV 5.2% | IBU 22 HORNY MONK BELGIAN DUBBEL Petoskey Brewing Co. // Petoskey, MI, USA | ABV 6.9% | IBU 20 DIABOLICAL IPA North Peak Brewing Co. // Traverse City, MI, USA | ABV 6.6% | IBU 67 ROTATING TAP Ask about today’s featured beer. GROWLERS (64oz.) ARE AVAILABLE ON ALL DRAFT BEER SELECTIONS Growler: $10 without fill | $5 with fill // Growler Fills: $12 domestic | $16 craft CRAFT | BOTTLED PALE ALE PALE ALE Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. // Chico, CA, USA | ABV 5.6% | IBU 37 PALE ALE Bass Brewery // Baldwinsville, NY, USA | ABV 5.1% | IBU 49 PALEOOZA New Holland Brewing Co. // Holland, MI, USA | ABV 5.8% | IBU 36 OMISSION PALE ALE {GF} Widmer Brothers Brewing Co. // Portland, OR, USA | ABV 5.8% | IBU 33 INDIA PALE ALE TWO HEARTED ALE Bell’s Brewery // Kalamazoo, MI, USA | ABV 7.0% | IBU 55 CENTENNIAL IPA Founders Brewing Co. // Grand Rapids, MI, USA | ABV 7.2% | IBU 65 HUMA LUPA LICIOUS Short’s Brewing Co. // Bellaire, MI, USA | ABV 7.7% | IBU 96 MAD HATTER MIDWEST INDIA PALE ALE New Holland Brewing Co. // Holland, MI, USA | ABV 7% | IBU 55 51K IPA Blackrocks Brewery // Marquette, MI, USA | ABV 7% | IBU 51 ROGUE YELLOW SNOW IPA Rogue Ales & Spirits // Newport, OR, USA | ABV 6.2% | IBU 70 SESSION BEER DAYTIME - A FRACTIONAL IPA Lagunitas Brewing Co. -

Fernanda Mara De Oliveira Macedo Carneiro Pacobahyba SECRETÁRIA DA FAZENDA

49 CÓDIGO FISCAL VALORES DE ESPÉCIE PRODUTO FABRICANTE EMBALAGEM UNIDADE DO PRODUTO REFERENCIA REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE RELVA GUARANA RELVA 03.001.0011.00082 PET UN 2,06 DESCARTAVEL 1L GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 1L REFRIGERANTES REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE RELVA LARANJA RELVA 03.001.0011.00118 PET UN 2,06 DESCARTAVEL 1L GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 1L REFRIGERANTES REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE RELVA LARANJA RELVA 03.001.0010.00201 PET UN 3,18 DESCARTAVEL 2L GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 2L REFRIGERANTES REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO CAJU 03.001.0011.00086 SAO GERALDO PET UN 4,58 DESCARTAVEL 1L GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 1L REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO CAJU 03.001.0016.00089 SAO GERALDO PET UN 1,75 DESCARTAVEL 250ML GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 250ML REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO LARANJA 03.001.0016.00092 SAO GERALDO PET UN 1,63 DESCARTAVEL 250ML GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 250ML REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO UVA 03.001.0016.00214 SAO GERALDO PET UN 1,28 DESCARTAVEL 250ML GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 250ML REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO CAJU 03.001.0010.00145 SAO GERALDO PET UN 5,96 DESCARTAVEL 2L GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 2L REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO CAJU 03.001.0048.00001 SAO GERALDO VIDRO UN 2,73 RETORNAVEL 600ML GARRAFA RETORNAVEL 600ML REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE SAO GERALDO CAJU 03.001.0023.00014 SAO GERALDO VIDRO UN 1,68 RETORNAVEL 200ML GARRAFA NS RETORNAVEL 200ML REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE GOSTIN GUARANA 03.001.0016.00191 SAO GERALDO PET UN 1,35 DESCARTAVEL 250ML GARRAFA PET DESCARTAVEL 250ML REFRIGERANTE REFRIGERANTE -

Commodities, Culture, and the Consumption of Pilsner Beer in The

Empire in a Bottle: Commodities, Culture, and the Consumption of Pilsner Beer in the British Empire, c.1870-1914 A dissertation presented by Malcolm F. Purinton to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts August 2016 1 Empire in a Bottle: Commodities, Culture, and the Consumption of Pilsner Beer in the British Empire, c.1870-1914 by Malcolm F. Purinton Abstract of Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University August, 2016 2 Abstract The Pilsner-style beer is the most popular and widespread beer style in the world with local variants and global brands all competing in marketplaces from Asia to Africa to the Americas. Yet no one has ever examined why this beer and not another was able to capture the global market for malt beverages. This is important from the point of view of the study of beer as a commodity, but its greater importance is in the way the spread of the Pilsner style serves as a visible, traceable marker for the changes wrought by globalization in an age of empire. Its spread was dependent not only on technological innovations and faster transportation, but also on the increased connectedness of the world, and on the political structures like empires that dominated the world at the time. Drawing upon a wide range of archival sources from Great Britain, Germany, Ireland, and South Africa, this study traces the spread in consumption and production of the Pilsner in the British Empire between 1870 and 1914. -

Allergen Information

Allergen Information Are you prepared? From 13th December 2014, it will be a legal requirement for you to inform your customers of products that contain any of 14 allergens. It will be a criminal offence not to do so. What must you do? As an outlet serving food and/or drink you must ensure you can provide information to customers about allergens in all non pre-packed food and drinks sold at your outlet before they make a food or drink purchase. You will see we have already taken care of the pre-packed products we supply to you. We have the allergens listed on all our packaged products and also our cask and keg labels. To help you, we have also listed all of the allergens of the draught Carlsberg UK products we supply to you in the table overleaf. What are the 14 allergens you need to provide information on? • Cereals containing gluten e.g. wheat, rye, barley, oats • Crustaceans e.g. prawns, lobster, crab • Molluscs e.g. clams, mussels, oysters • Eggs • Fish • Peanuts • Other nuts e.g. almonds, hazelnuts, cashews • Celery and celeriac e.g. stalks, seeds and leaves • Soya e.g. soya sauce, tofu/beancurd • Milk • Mustard • Sesame seeds • Sulphur dioxide and sulphites • Lupin seeds and flour How can you provide this information? You need to let customers know that allergen information is available upon request. However, how you inform them is up to you. Examples include: • Labels, tickets or stickers; • Printed menus or lists so that customers don’t need to ask; • Signs, blackboards or POS notifications; and/or • Verbal information from staff (although written verification of the verbal information must also be available). -

Internal Memorandum

Cider not recognised as being real Below is a list of the most common ciders that CAMRA does not recognise as being real. Please note that this is not an exhaustive list. The most common reasons a cider or perry is not considered to be real are that it is carbonated, pasteurised, micro-filtered, or concentrate juice has been used. The most common ciders confused for being real are: • Addlestones • Bulmers Traditional • Kingstone Press (by Aston Manor) • Rattler • Sheppy's Oakwood • Stowford Press (Westons) • Taunton Traditional • Thatchers Gold • Thatchers - in bottles & cans • Thistly Cross (except Jaggy Thistle, which is real) • Westons Ice • Westons - in bottles & cans • 'any cider that has been carbonated' • 'any cider with added flavourings EXCEPT pure fruits, vegetables, honey, hops, herbs and spices' • 'any cider with any concentrates, cordials or essences added' However, there are many others, for example: • Amber Harvest (Aston Manor) • Ashton Press • Aspall (except Temple Moon, Cyderkyn and Waddlegoose Lane, which are real) • Bounders (Bath Cider) • Briska • Brothers • Bulmers • Chaplin and Cork • Chardolini Perry (Aston Manor) • Copper Press (St Austell) • Crofter's (Aston Manor) • Crumpton (Aston Manor) • Diamond White • Druids Celtic Cider (Aston Manor) • Dry Blackthorn • Duchy Originals (Aston Manor) • Friels • Frome Valley Cider not recognised as being real • Frosty Jack's • Gaymer's • Golden Valley (Aston Manor) • Harry Sparrow (Aspall) • Hereford Orchard (Aston Manor) • Jacques • K Cider • Knights (Aston Manor) • Kopparberg • Lazy Jacks • Magners • Malvern Gold (Aston Manor) • Merrydown • Natch • Oakleys • Old Moors (Devon Cider Co.) • Old Mout • Pomagne • Red C • Rekorderlig • Robinsons • SKU • Samuel Smith's • Scrumpy Dog • Scrumpy Jack • Sharp's Orchard Cornish • Somersby (Carlsberg) • St Helier • Stella Cidre • Strongbow • Strongbow Sirrus • Symonds • Taunton • Three Hammers (Aston Manor) • Tomos Watkin • WKD Core • White Lightning • White Star • Woodpecker . -

Heineken Brewery Pricing Schedule 2019

HUK WSP Price Schedule Effective Midnight 31st January 2019 Effective Midnight 3rd February 2019 AWSR URN: XTAW00000102336 DUTY CHANGE : Effective Midnight 31st January 2019 HUK INCREASE: Effective Midnight 3rd February 2019 Product ABV Container Old Price New Price Increase Old Price New Price Increase Old Price New Price Increase Old Price New Price Increase £/Container £/Container £/Container £/Brl £/Brl £/Brl £/Container £/Container £/Container £/Brl £/Brl £/Brl Lager AMSTEL 4.1 50L / 11G £ 189.34 £ 189.34 £ - £ 189.34 £ 196.38 £ 7.04 AMSTEL 4.1 100L / 22G £ 378.68 £ 378.68 £ 619.52 £ 619.52 £ 378.68 £ 392.76 £ 14.08 £ 619.52 £ 642.56 £ 23.04 BIRRA MORETTI 8L BREWLOCK IMPORT 4.6 8L £ 43.71 £ 894.18 BIRRA MORETTI BREWLOCK 4.6 20L / 4.4G £ 85.35 £ 85.35 £ 698.42 £ 698.42 £ - £ 85.35 £ 88.17 £ 2.82 £ 698.42 £ 721.46 £ 23.04 BIRRA MORETTI *** 4.6 30L / 6.6G £ 126.63 £ 126.63 £ - £ 690.80 £ 690.80 £ - £ 126.63 £ 130.85 £ 4.22 £ 690.80 £ 713.81 £ 23.01 BIRRA MORETTI 4.6 50L / 11G £ 211.06 £ 211.06 £ - £ - £ 211.06 £ 218.10 £ 7.04 CRUZCAMPO 4.8 30L / 6.6G £ 116.89 £ 116.89 £ - £ 637.65 £ 637.65 £ - £ 116.89 £ 121.11 £ 4.22 £ 637.65 £ 660.67 £ 23.02 FOSTERS * 4.0 50L / 11G £ 170.48 £ 170.48 £ - £ 557.98 £ 557.98 £ - £ 170.48 £ 175.76 £ 5.28 £ 557.98 £ 575.26 £ 17.28 FOSTERS 4.0 100L / 22G £ 340.98 £ 340.98 £ - £ 557.84 £ 557.84 £ - £ 340.98 £ 351.54 £ 10.56 HEINEKEN 8L BREWLOCK KEG IMPORT 5.0 8L £ - £ 40.89 £ 836.49 HEINEKEN 5.0 20L / 4.4G £ 90.19 £ 90.19 £ - £ 738.03 £ 738.03 £ - £ 90.19 £ 93.01 £ 2.82 £ 738.03 £ 761.06 £ 23.03 HEINEKEN -

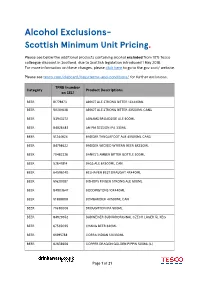

Alcohol Exclusions- Scottish Minimum Unit Pricing

Alcohol Exclusions- Scottish Minimum Unit Pricing. Please see below the additional products containing alcohol excluded from 10% Tesco colleague discount in Scotland, due to Scottish legislation introduced 1 May 2018. For more information on these changes, please click here to go to the gov.scot/ website. Please see tesco.com/clubcard/help/terms-and-conditions/ for further exclusions. TPNB (number Category Product Descriptions on SEL) BEER 81779873 ABBOT ALE STRONG BITTER 12X440ML BEER 50281638 ABBOT ALE STRONG BITTER 4X500ML CANS BEER 53943272 ADNAMS BROADSIDE ALE 500ML BEER 84828483 AM PM SESSION IPA 330ML BEER 51244624 BADGER TANGLEFOOT ALE 4X500ML CANS BEER 84794622 BADGER WICKED WYVERN BEER 6X330ML BEER 70482226 BANKS'S AMBER BITTER BOTTLE 500ML BEER 52647814 BASS ALE 6X500ML CAN BEER 64596740 BELHAVEN BEST DRAUGHT 4X440ML BEER 51620087 BISHOPS FINGER STRONG ALE 500ML BEER 84903647 BODDINGTONS 10X440ML BEER 51388808 BOMBARDIER 4X500ML CAN BEER 77630006 BROUGHTON IPA 500ML BEER 84929352 BUDWEISER BUDVARORIGINAL CZECH LAGER 5L KEG BEER 67535025 CHANG BEER 620ML BEER 61895788 COBRA INDIAN 12X330ML BEER 62678606 COPPER DRAGON GOLDEN PIPPIN 500ML (L) Page 1 of 21 BEER 61360407 CWRW BRAF 500ML BEER 85103567 DESPERADOS LAGER BEER 5 LTR KEG BEER 64608152 DEUCHARS IPA 4X500ML BEER 52786453 EXMOOR GOLD 500ML (L) BEER 52465902 FULLERS 1845 STRONG ALE 500ML BEER 84980076 FULLERS LONDON PRIDE ALE6 X 330ML BEER 63080643 FURSTY FERRET 4X500ML CAN BEER 66485782 GREENE KING ABBOT RESERVE 500ML BEER 81779882 GREENE KING HEN'S TOOTH ALE 500ML BEER 84419086 GREENE KING HERITAGE SUFFOLKPALE ALE 568ML BEER 79928343 GREENE KING IPA 15 X 440ML BEER 51636224 GREENE KING IPA 4X500ML CANS BEER 57061911 GREENE KING IPA 500ML BEER 84605652 GREENE KING YARDBIRD PALE ALE CANS 6X330ML BEER 72503407 GUINNESS DRAUGHT 12 X 440ML BEER 50984129 GUINNESS DRAUGHT 4X440ML N.I.