Contract Farming Roopam.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalassessmentandaccredit

Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council Bangalore, 560 072. KARNATAKA, INDIA (2016-2017) 1. To empower the women folk of the society through a globally relevant and qualitatively enriched education. 2. To enable her to be a vital force to explore her potential to expedite the changes required to keep pace with advancing scenario while living a life of dignity. 3. To provide a learning environment to the women of rural as well as urban areas capacitating her to exemplify the rich heritage of Indian culture besides productively contributing vocationally and professionally to the cause of social uplift and nation building as an asset shedding all fears, apprehensions and age old superstitions. 1. To provide need based higher education to the young girls of the city and adjoining villages through multi-natured academic programmes through UG and PG degree courses and diplomas. 2. To capacitate them through professional degree courses so that they get equipped with skill, knowledge and practical acumen helping them to be employable or fit for self-employment to lead a life of economic independence. 3. To inculcate moral values among the students to emerge as ethical, tolerant and responsible citizens. 4. To expose them to different competitions, contests, debates and deliberations individually and collaboratively through extra & co- curricular activities for a holistic personality development. 5. Women empowerment, a process of acquiring knowledge and awareness enabling them to move towards life with greater dignity and self-confidence. 6. To provide women education in all areas of learning to eliminate gender inequality and to ensure equality before law and to prepare them for a life of challenges ahead. -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB -

DISTRICT HOSHIARPUR Sr. No. Name of Block Name of Village

DISTRICT HOSHIARPUR Sr. Name of Block Name of Village Name of Grampanchyat Hadbast No. No. BHUNGA 1. Abowal Abowal 520 2. Adamwal Garhi Adamwal Garhi 389 3. Ambala Jattan Ambala Jattan 32 4. Argowal Argowal 10 5. Alarpind Alarpind 34 6. Arniala Shahpur Arniala Shahpur 491 7. Atwarapur Atwarapur 482 8. Badala Badala 511 9. Bahtiwala Bahtiwala 448 10. Bainch Bainch 507 11. Birampur Birampur 48 12. Bhala Bhala 47 13. Bariana Bariana 68 14. Bari Khad Bari Khad 473 15. Barohi Barohi 463 16. Bassi Bazid Bassi Bazid 422 17. Bhaliala Bhaliala 421 18. 1. Bassi Balo Bassi Balo 417 2. Bassi Bahadur 415 19. Bassi Umar Khan Bassi Umar Khan 402 20. Bhagowal Bhagowal 85 21. Bhana Bhana 3 22. Bhanowal Bhanowal 451 23. 1. Bhattian Bhattian 27 2. Mahal 26 24. Bagha Bagha 39 25. Bhatlan Bhatlan 452 26. Bhullana Bhullana 67 27. Bhunga Bhunga 521 28. 1. Balala Balala 20 2. Gardhiwala (out side 19 Municipal) 29. Baranda Baranda 447 30. 1. Basi Babu Khan Basi Babu Khan 414 2. Khanpur 408 31. 1. Basi Kale Khan Basi Kale Khan 407 1 Sr. Name of Block Name of Village Name of Grampanchyat Hadbast No. No. 2. Shazadpur 416 32. Basi Wahid Basi Wahid 398 33. Badial Badial 11 34. Bhatolian Bhatolian 523 35. 1. Bahera Bahera 474 2. Barum 475 36. Bhabowal Bhabowal 445 37. Chak ladian Chak ladian 435 38. Chohak Chohak 22 39. Chotala Chotala 58 40. Chak Sotla Chak Sotla 525 41. Chak Khela Chak Khela 509 42. Chhumerhy Chhumerhy 478 43. Chak Gujjran Chak Gujjran 396 44. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administrative Detail of Repair Approval Sr

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administrative Detail of Repair Approval Sr. Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Distt. MC Name of Work Strengthe Premix No. Length Cost Raising Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 1 Hoshiarpur Mukerian NHIA to Dasuya Hajipur Road 16.96 186.44 3.03 5.11 16.96 Co. [Gr.No.1] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 2 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian to Dasuya Hajipur road 10.65 130.85 1.68 2.35 10.65 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 Mukerian Hajipur road to Dallowal & link M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 3 Hoshiarpur Mukerian 0.5 6.33 0.04 0.38 0.5 to Phirni of vill. Dallowal Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 4 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian Hajipur road to Ralli 1.42 16.87 0.44 0.17 1.42 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 5 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian Hajipur road to Jahidpur 0.5 5.98 -- 0.3 0.5 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 Mukerian Hajipur road to Dallowal & link M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 6 Hoshiarpur Mukerian 1.2 16.34 0.2 0.81 1.2 to Phirni of vill. -

Crystal Reports

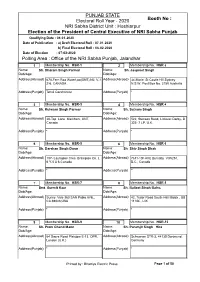

PUNJAB STATE Electoral Roll Year - 2020 Booth No : NRI Sabha District Unit : Hoshiarpur Election of the President of Central Executive of NRI Sabha Punjab Qualifying Date : 04-01-2020 Date of Publication : a) Draft Electoral Roll : 07-01-2020 b) Final Electoral Roll : 06-02-2020 Date of Election : 07-03-2020 Polling Area : Office of the NRI Sabha Punjab, Jalandhar 1 Membership No. HSR-1 2 Membership No. HSR-2 Name: Sh. Dharam Singh Parmar Name: Sh. Jaspreet Singh Dob/Age: Gender : Male Dob/Age: Gender : Male Address(Abroad) 670-Fern Roa Waterl;oo(ONT),N2, V-1 Address(Abroad) 34-Marie St Castle Hill Sydney Z-6, CANADA N.S.W. Post Box No. 2150 Australia Address(Punjab) Tehsil Garshankar Address(Punjab) " 3 Membership No. HSR-3 4 Membership No. HSR-4 Name: Sh. Kulwarn Singh Parmar Name: Sh. Satnam Singh Dob/Age: Gender : Male Dob/Age: Gender : Male Address(Abroad) 20-Top Lane Markham, ONT, Address(Abroad) 522, Stenson Road, Littlover-Derby- D Canada 323- 7 LP, U.K. Address(Punjab) " Address(Punjab) " 5 Membership No. HSR-5 6 Membership No. HSR-6 Name: Sh. Darshan Singh Darar Name: Sh Shiv Singh Dhak Dob/Age: Gender : Male Dob/Age: Gender : Male Address(Abroad) 107- Lauraglen Cres Brampton On. L Address(Abroad) 7611-10h AVE Burnaby V3N251, 6 Y-5 A 6-Canada B.C., Canada Address(Punjab) " Address(Punjab) "' 7 Membership No. HSR-7 8 Membership No. HSR-8 Name: Smt. Gurmit Kaur Name: Sh. Baljeet Singh Bains Dob/Age: Gender : Male Dob/Age: Gender : Male Address(Abroad) Sunny Vale 363 SAN Pablo AVE., Address(Abroad) 42, Tudor Road South Hall Middx , UB CA.94086,USA 11 NX., U.K. -

POLICE DEPARTMENT DISTT SBS NAGAR LIST of PROCLAIMED OFFENDER's 82/83 Crpc.(PO's) S NO NAME & ADDRESS of PO FIR NO.,DATE

POLICE DEPARTMENT DISTT SBS NAGAR LIST OF PROCLAIMED OFFENDER's 82/83 CrPC.(PO’s) S NAME & ADDRESS OF PO FIR NO.,DATE, U/S & PS PS P.O DATE HEAD OF CRIME RESIDENCE NO DISTT PS CITY NAWANSHAHAR TERRORIST CASES P.Os 1 GURTIRATH SINGH S/O FIR No .44 DT.27/07/1992 CITY NSR 05/06/1993 HEINOUS HOME DISTT SANTOKH SINGH V. MUSAPUR 307/34 IPC 24/54/59 A ACT PS BANGA DISTT. SBS NAGAR 3/4 TDA(P) ACT PS CITY STATE PUNJAB NAWANSHAHAR 2.FIR No.109 DT.02/10/1991 CITY NSR 19/05/1998 307/148/149 IPC 3/4/5 TDA (P) ACT PS CITY NAWANSHAHAR 2 SATNAM SINGH @ SATTI S/O FIR No .12 DT.02/01/1993 CITY NSR 13/11/96 HEINOUS HOME DISTT MALKIAT SINGH V. BHANGAL 212/216-A IPC 5/6 TDAP PS KALAN PS SADAR NSR DISTT. CITY NAWANSHAHAR SBS NAGAR STATE PUNJAB 2.FIR No.90 DT.29/04/1987 CITY NSR 01/09/1997 18/61/85 NDPS ACT 25/54/ 56 A ACT PS CITY NAWANSHAHAR 3 GURNEK SINGH @ MEEKA S/O FIR No .148 DT.21/06/1987 CITY NSR 15/03/1992 HEINOUS OUT OF DISTT PRITAM SINGH V. MEHRAMPUR 302/307/353/186 IPC 3/4 PS NAKODER TDAP ACT PS SADAR DISTT.JALANDHAR STATE NAWANSHAHAR PUNJAB TO CITY NSR 4 GURNEK SINGH S/O SOHAN FIR No .180 DT.21/11/1989 CITY NSR 09/11/1991 HEINOUS HOME DISTT SINGH V. HIYALA PS SADAR 302/34 IPC 25/54/59 A ACT NSR DISTT. -

The Sikh Diaspora Global Diasporas Series Editor: Robin Cohen

The Sikh diaspora Global diasporas Series Editor: Robin Cohen The assumption that minorities and migrants will demonstrate an exclusive loyalty to the nation-state is now questionable. Scholars of nationalism, international migration and ethnic relations need new conceptual maps and fresh case studies to understand the growth of complex transnational identities. The old idea of “diaspora” may provide this framework. Though often conceived in terms of a catastrophic dispersion, widening the notion of diaspora to include trade, imperial, labour and cultural diaporas can provide a more nuanced understanding of the often positive relationships between migrants’ homelands and their places of work and settlement. This book forms part of an ambitious and interlinked series of volumes trying to capture the new relationships between home and abroad. Historians, political scientists, sociologists and anthropologists from a number of countries have collaborated on this forward-looking project. The series includes two books which provide the defining, comparative and synoptic aspects of diasporas. Further titles, of which The Sikh diaspora is the first, focus on particular communities, both traditionally recognized diasporas and those newer claimants who define their collective experiences and aspirations in terms of a diasporic identity. This series is associated with the Transnational Communities Programme at the University of Oxford funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council. Already published: Global diasporas: an introduction Robin Cohen New diasporas Nicholas Van Hear Forthcoming books include: The Italian labour diaspora Donna Gabaccia The Greek diaspora: from Odyssey to EU George Stubos The Japanese diaspora Michael Weiner, Roger Daniels, Hiroshi Komai The Sikh diaspora The search for statehood Darshan Singh Tatla © Darshan Singh Tatla 1999 This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. -

List of 3500 VLE Cscs in Punjab

Sr No District Csc_Id Contact No Name Email ID Subdistrict_Name Village_Name Village Code Panchayat Name Urban_Rural Kiosk_Street Kiosk_Locality 1 Amritsar 247655020012 9988172458 Ranjit Singh [email protected] 2 Amritsar 479099170011 9876706068 Amot soni [email protected] Ajnala Nawan Pind (273) 37421 Nawan Pind Rural Nawanpind Nawanpind 3 Amritsar 239926050016 9779853333 jaswinderpal singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Dolonangal (33) 37710 Baba Sawan Singh Nagar Rural GALI NO 5 HARSANGAT COLONY BABA SAWAN SINGH NAGAR 4 Amritsar 677230080017 9855270383 Barinder Kumar [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000532 \N Urban gali number 5 vishal vihar 5 Amritsar 151102930014 9878235558 Amarjit Singh [email protected] Amritsar -I Abdal (229) 37461 Abdal Rural 6 Amritsar 765534200017 8146883319 ramesh [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000532 \N Urban gali no 6 Paris town batala road 7 Amritsar 468966510011 9464024861 jagdeep singh [email protected] Amritsar- II Dande (394) 37648 Dande Rural 8 Amritsar 215946480014 9569046700 gursewak singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Saido Lehal (164) 37740 Saido Lehal Rural khujala khujala 9 Amritsar 794366360017 9888945312 sahil chabbra [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000540 \N Urban SARAIN ROAD GOLDEN AVENUE 10 Amritsar 191162640012 9878470263 amandeep singh [email protected] Amritsar -I Athwal (313) 37444 \N Urban main bazar kot khalsa 11 Amritsar 622551690010 8437203444 sarbjit singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Butala (52) 37820 Butala Rural VPO RAJPUR BUTALA BUTALA 12 Amritsar 479021650010 9815831491 hatinder kumar [email protected] Ajnala \N 9000535 \N Urban AMRITSAR ROAD AJNALa 13 Amritsar 167816510013 9501711055 Niketan [email protected] Baba Bakala \N 9000545 \N Urban G.T. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 98, MAULANA AZAD ROAD, PORT BLAIR, ANDAMAN Andaman & 744101, AND Nicobar State ANDAMAN & NICOBAR Coop Bank NICOBAR ISLAND ANDAMAN Ltd ISLAND PORT BLAIR HDFC0CANSC9434281460 - HDFC BANK LTD. 201, MAHATMA GANDHI ROAD, JUNGLIGHAT, ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR AND ANDAMAN & NICOBAR NICOBAR ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR 744103 PORT BLAIR HDFC000199498153 31111 HDFC BANK LTD6-2- ANDHRA 57,CINEMA PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD ROAD ADILABAD HDFC0001621022-61606161 SURVEY NO.109 5 PLOT NO. 506 28-3-100 BELLAMPALL I ANDHRA ANDHRA BELLAMPALL PRADESH BELLAMPALL PRADESH ADILABAD I 504251 I HDFC000260399359 03333 NO. 6-108/5, OPP. VAGHESHWA RA JUNIOR COLLEGE, BEAT BAZAR, LAXITTIPET ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH LAKSHATHIP PRADESH ADILABAD LAXITTIPET 504215 ET HDFC000303699494 93333 - 18-6-49, AMBEDKAR CHOWK, MUKHARAM PLAZA, NH- 16, CHENNUR ROAD, MANCHERIA MANCHERIA L ANDHRA ANDHRA L - ANDHRA PRADESH MANCHERIY PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504208 AL HDFC000074398982 71111 NO.1-2-69/2, NH-7, OPPOSITE NIRMAL BUS DEPO, ANDHRA NIRMAL PIN PRADESH ADILABAD NIRMAL 504106 NIRMAL HDFC000204498153 31111 #5- 495,496,Gaya tri Towers,Iqbal Ahmmad Ngr,New MRO THE GAYATRI Office-Opp CO-OP Strt,Vill&Mdl: ANDHRA URBAN Mancherial:Ad MANCHERIY PRADESH ADILABAD BANK LTD ilabad.A.P AL HDFC0CTGB09248945222 - Vysya Bank Universal Road, ANDHRA Coop Urban Mancherial- MANCHERIY PRADESH ADILABAD Bank Ltd 504208 AL HDFC0CUCUB7382030261 - 11-129, SREE BALAJI RESIDENCY, ANANTHAPU SUBHASH ANDHRA R - ANDHRA ROAD, PRADESH ANANTAPUR PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR -

Punjab Circle Vide Notification No.STC/18-50/GDS ONLINE II

VacancyJobAlert.Com Selection list of Gramin Dak Sevak for Punjab circle vide Notification No.STC/18-50/GDS ONLINE II S.No Division HO Name SO Name BO Name Post Name Cate No Registration Selected Candidate gory of Number with Percentage Post s 1 Chandigarh Chandigarh Baltana S.O Baltana S.O GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR44A9412F6BF9 SHAFFY- (95)-UR G.P.O. Dak Sevak 2 Chandigarh Chandigarh Chandigarh Balongi B.O GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR0BCDF43EE4E5 MANDEEP- G.P.O. Sector 55 S.O Dak Sevak (97.6667)-UR 3 Chandigarh Chandigarh Chandigarh Chandigarh GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR817EF4D819EC KAMALJEET- G.P.O. Sector 55 S.O Sector 55 S.O Dak Sevak (97.8333)-UR 4 Chandigarh Chandigarh Ind Area Ram Darbar GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR3A7F449D6734 RAKESH KUMAR- G.P.O. Chandigarh S.O Dak Sevak (98)-OBC S.O 5 Chandigarh Chandigarh Lalru S.O Jauli B.O GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR054ABF5FEE77 MONU- (97.6667)- G.P.O. Dak Sevak UR 6 Chandigarh Chandigarh Maloya Maloya GDS ABPM/ SC 1 CR1FF36A314337 VIKRAM SINGH- G.P.O. Colony S.O Colony S.O Dak Sevak (97.5)-SC 7 Chandigarh Chandigarh Manimajra Daria B.O GDS BPM SC 1 CR148284D23566 RAHUL KUMAR- G.P.O. S.O (97.4)-SC 8 Chandigarh Chandigarh Manimajra Kishangarh GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR2F76DD15B827 RINKI- (99.4)-UR G.P.O. S.O B.O Dak Sevak 9 Chandigarh Chandigarh Mubarakpur Mubarakpur GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR1B1395FEDCC GULSHAN- (97.5)- G.P.O. S.O (Patiala) S.O (Patiala) Dak Sevak B UR 10 Chandigarh Chandigarh Sector 12 Sector 12 GDS ABPM/ UR 1 CR8A46EF593A33 JAIMAL- (97.8)-UR G.P.O. -

ANNEXURE a OFFICE of the DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE, JALANDHAR List of Candidates to Be Called for Interview F

ANNEXURE A OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE, JALANDHAR List of candidates to be called for interview for the post of Peon (including Peon, Orderly, Waterman, Chowkidar, Mali etc.) Father/ Husband Roll No. Candidate Name Date of Birth Address Name H.NO. 72-B, DILBAGH NAGAR, BASTI GUZAN, 1 PUNEET ARORA KIRAN ARORA 11-09-1988 JALANDHAR 2 BALJINDER SINGH GURSEWAK SINGH 05-11-1996 V.P.O CHARIK PATTI JANGIR DISTT. MOGA 3 AMARDEEP SINGH RAJINDER SINGH 16-06-1993 VPO SIRTHALA TEHSIL PAYAL DISTT. LUDHIANA 4 BUDH RAM BIRBHAN 05-08-1992 WNO. 6, NEAR BALMIK MANDIR, MOONAK,SANGRUR 5 MANDEEP SINGH BEER BHAN 15-05-1994 WNO. 6, MOONAK DISTT. SANGRUR WNO. 12, NEAR BALMIK TEMPLE, MOONAK, DISTT. 6 MANDEEP SINGH PAWAN KUMAR 16-04-1995 SANGRUR. COMMISSIONER COMPLEX NEAR NEW COURT. H.NO. 7 AMIT KUMAR SHARMA KEWAL RAM SHARMA 11-03-1992 DX691, JALANDHAR CITY 8 ANU MAKHAN PARSHAD 08-04-1995 20B, NEW BRADARI, JALANDHAR 9 BAHADUR SINGH PARAMJIT SINGH 14-07-1996 VPO KHUN-KHUN KALAN, HOSHIARPUR 10 RAMANDEEP SINGH GURJANT SINGH 31-08-1997 VILLAGE CHEEMA MOGA PUNJAB 11 MANVEER SINGH GURCHARAN SINGH 01-03-1997 VILLAGE GOGOANI, FEROZEPUR, PUNJAB H.NO. 208, VN PARK NANDANPUR ROAD, 12 KANHIEYA LALU PARSHAD 10-10-1996 MAQSUDAN, JALANDHAR 326-C, EKTA NAGAR, P.O CHUGTTI, NEAR TATA 13 VINOD SEMWAL CHAKARDHAR SEMWAL 20-04-1984 TOWER, JALANDHAR 14 BIPAN KUMAR SHRI LAL 02-02-1997 HNO.35, KIRTI NAGAR LADOWALI ROAD JALANDHAR 15 DALIP KUMAR SHREE LAL GUPTA 02-03-1999 HNO.35, KIRTI NAGAR LADOWALI ROAD JALANDHAR HNO.08,COURT ROAD WARD NO.9, NEAR WATER 16 SHUBH SH.AMRIK SINGH 11-09-1993 TANK NAKODAR DISTT.JALANDHAR 17 IQBAL SINGH MALKIT SINGH 03-01-1986 V.P.O. -

S. No. District School Subject Vacancy 1 Amritsar GGHS NANGAL MEHTA

District School Subject Vacancy S. No. 1 Amritsar GGHS NANGAL MEHTA Punjabi 1 2 Amritsar GGHS SATHIALA Punjabi 1 3 Amritsar GGS ATTARI Punjabi 1 4 Amritsar GGSS AJNALA Punjabi 1 5 Amritsar GGSS BUTALA Punjabi 1 6 Amritsar GGSS TAPIALA Punjabi 3 7 Amritsar GHS BHALA PIND Punjabi 1 8 Amritsar GHS BHILOWAL PACCA Punjabi 2 9 Amritsar GHS BHINDI AULAKH Punjabi 2 10 Amritsar GHS BUDDA THEH Punjabi 1 11 Amritsar GHS BUTTAR DHARDEO Punjabi 1 12 Amritsar GHS DAUKE Punjabi 1 13 Amritsar GHS DHARIWAL KALER Punjabi 1 14 Amritsar GHS GAGGAR BHANA Punjabi 1 15 Amritsar GHS JALALPURA Punjabi 1 16 Amritsar GHS JASRAUR Punjabi 3 17 Amritsar GHS JATTA PACHHIAN Punjabi 1 18 Amritsar GHS JHANDER Punjabi 1 19 Amritsar GHS KAKKAR Punjabi 1 20 Amritsar GHS MEHARBANPURA Punjabi 2 21 Amritsar GHS PREETNAGAR Punjabi 1 22 Amritsar GHS RASOOLPUR KALAN Punjabi 1 23 Amritsar GHS SUDHAR RAJPUTAN Punjabi 1 24 Amritsar GHS UGGAR AULAKH Punjabi 1 25 Amritsar GHS WADALA KALAN WADALA KHURD Punjabi 1 26 Amritsar GHS WARRAICH Punjabi 1 27 Amritsar GMS ARJUN MANGA Punjabi 1 28 Amritsar GMS AWAN Punjabi 1 29 Amritsar GMS BHANGWAN Punjabi 1 30 Amritsar GMS BHATTIKE Punjabi 1 31 Amritsar GMS BHILOWA RMSA UPGRADED Punjabi 1 32 Amritsar GMS CHAINPUR BALLAGGAN Punjabi 1 33 Amritsar GMS CHOWNK MEHTA Punjabi 1 34 Amritsar GMS DAGG Punjabi 1 35 Amritsar GMS DAUKE UPGRADED Punjabi 1 36 Amritsar GMS DHARIWAL KALER RMSA UPGRADED Punjabi 1 37 Amritsar GMS DUJJOWAL Punjabi 1 38 Amritsar GMS JAFARKOT Punjabi 1 39 Amritsar GMS JAMALPUR Punjabi 1 40 Amritsar GMS JATHAUL Punjabi 1 41 Amritsar