Heikki Ruismäki & Inkeri Ruokonen (Eds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

360 Degrees Focus on Lighting Design

360 Degrees: Focus on Lighting Design on Lighting 360 Degrees: Focus 360 Degrees Focus on Lighting Design (Edited by) TOMI HUMALISTO, KIMMO KARJUNEN, RAISA KILPELÄINEN 70 THE PUBLICATION SERIES OF THE THEATRE ACADEMY RAISA KILPELÄINEN RAISA KIMMO KARJUNEN, KARJUNEN, KIMMO TOMI HUMALISTO, Edited by Edited 360 Degrees Focus on Lighting Design TOMI HUMALISTO, KIMMO KARJUNEN, RAISA KILPELÄINEN (ED.) TOMI HUMALISTO, KIMMO KARJUNEN, RAISA KILPELÄINEN (ED.) 360 Degrees Focus on Lighting Design PUBLISHER University of the Arts Helsinki, Theatre Academy 2019 University of the Arts Helsinki, Theatre Academy, Editor & Writers THE PUBLICATION SERIES OF THE THEATRE ACADEMY VOL 70 ISBN (print): 978-952-353-010-2 ISBN (pdf): 978-952-353-011-9 ISSN (print): 0788-3385 ISSN (pdf): 2242-6507 GRAPHIC DESIGN BOND Creative Agency www.bond.fi COVER PHOTO Kimmo Karjunen LAYOUT Atte Tuulenkylä, Edita Prima Ltd PRINTED BY Edita Prima Ltd, Helsinki 2019 ISTÖM ÄR ER P K M K PAPER Y I Scandia 2000 Natural 240 g/m2 & Maxi offset 100 g/m2 M I KT FONTS LJÖMÄR Benton Modern Two & Monosten Painotuotteet 4041 0002 360 Degrees Focus on Lighting Design TOMI HUMALISTO, KIMMO KARJUNEN, RAISA KILPELÄINEN (ED.) 70 THE PUBLICATION SERIES OF THE THEATRE ACADEMY Contents Introduction 9 PART I Multidisciplinary perspectives on lighting design 13 Tarja Ervasti Found spaces, tiny suns 13 Kimmo Karjunen Creating new worlds out of experimentation 37 Raisa Kilpeläinen Thoughts on 30 years of lighting design education at the Theatre Academy 59 Kaisa Korhonen Memories and sensations – the -

See Helsinki on Foot 7 Walking Routes Around Town

Get to know the city on foot! Clear maps with description of the attraction See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 1 See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 6 Throughout its 450-year history, Helsinki has that allow you to discover historical and contemporary Helsinki with plenty to see along the way: architecture 3 swung between the currents of Eastern and Western influences. The colourful layers of the old and new, museums and exhibitions, large depart- past and the impact of different periods can be ment stores and tiny specialist boutiques, monuments seen in the city’s architecture, culinary culture and sculptures, and much more. The routes pass through and event offerings. Today Helsinki is a modern leafy parks to vantage points for taking in the city’s European city of culture that is famous especial- street life or admiring the beautiful seascape. Helsinki’s ly for its design and high technology. Music and historical sights serve as reminders of events that have fashion have also put Finland’s capital city on the influenced the entire course of Finnish history. world map. Traffic in Helsinki is still relatively uncongested, allow- Helsinki has witnessed many changes since it was found- ing you to stroll peacefully even through the city cen- ed by Swedish King Gustavus Vasa at the mouth of the tre. Walk leisurely through the park around Töölönlahti Vantaa River in 1550. The centre of Helsinki was moved Bay, or travel back in time to the former working class to its current location by the sea around a hundred years district of Kallio. -

Happy Times in Helsinki Holiday Fun for Families 2014

ENGLISH INCLUDES COUPONS WITH Happy times SPECIAL OFFERS! in Helsinki p.10 Holiday fun for families 2014 Check out my holiday photos! 2 www.visithelsinki.fi Welcome to Helsinki! Hi, I’m Helppi from Helsinki and I love exploring. I’ve made a photo album with pictures of my favourite places in the city, local specialties, my furry © NIKLAS SJÖBLOM animal friends and me too of course! Take a look at my album and join me for an adventure! Let’s say hi to the mischievous Barbary ape at Helsinki Zoo, go for a ride on Kingi, the new ride at Linnanmäki Amusement Park, see the dinosaurs at the Natural History Museum and so much more! Inside my album you will find coupons with great special offers for exploring Helsinki. You can pick up maps and get great tips from Tourist Information ■ Me, Helsinki’s very own mascot. opposite the Market Square. You might even bump into me! You’ll recognise me from my spots. Hope to see you soon! Helppi Tourist Information Pohjoisesplanadi 19, Helsinki Tel. +358 (0)9 3101 3300 www.visithelsinki.fi www.visithelsinki.fi 3 Useful tips for a successful visit! © RAMI HANAFI RAMI © ■ Bus, metro, tram, even on your dad’s shoulders – it’s easy to get around Helsinki! Getting around easily When your tummy rumbles With our great public transport system, I love Winter, spring, summer or fall – you need to exploring different parts of Helsinki, both near eat every day! Here you will find some great and far. Listen to the humming of the tram restaurant tips: tracks, the swish of the metro tunnels and ■ www.visithelsinki.fi the splashing of the waves as you admire the ■ www.eat.fi views through the tram windows, race under- You will also come across all kinds of interesting ground in the metro and cruise around the pop-up restaurants in the city’s parks, on street islands on a ferry. -

Usc Thornton Oriana Women's Choir and Apollo Men's Chorus

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA THORNTON SCHOOL OF MUSIC USC THORNTON ORIANA WOMEN’S CHOIR AND APOLLO MEN’S CHORUS FRIDAY | OCTOBER 28, 2016 | 8:00PM NEWMAN RECITAL HALL ORIANA WOMEN’S CHOIR IRENE APANOVITCH conductor MICHAEL DAWSON co-conductor ASHLEY RAMSEY co-conductor HANBO MA accompanist APOLLO MEN’S CHORUS ERNEST H. HARRISON conductor SCOTT RIEKER co-conductor DA’JON JAMES co-conductor LUIS REYES accompanist PROGRAM ORIANA WOMEN’S CHOIR PABLO CASALS Eucaristica Ashley Ramsey, conductor CHARLES IVES At the River Irene Apanovitch, conductor RANDALL THOMPSON “A Girl’s Garden” from Frostiana Irene Apanovitch, conductor MICHAEL MCGLYNN The White Rose Michael Dawson, conductor GIDEON KLEIN Bachuri Le’an Tisa Ashley Ramsey, conductor Katharine LaMattina, soloist EUGENE SUCHON Bodaj by vás čerti vzali Michael Dawson, conductor MICHAEL MCGLYNN, arr. Song for Jerusalem Michael Dawson, conductor Sunmi Shin, soloist Kathy Tu, soloist Clare Wallmark, soloist SRUL IRVING GLICK “Psalm 23” from Psalm Trilogy Irene Apanovitch, conductor OSCAR PETERSON Hymn to Freedom Irene Apanovitch, conductor APOLLO MEN’S CHORUS MICHAEL COX Praise him! Ernest H. Harrison, conductor MXOLISI MATYILA Bawo Thixo Somnadla Mxolisi Matyila Ernest H. Harrison, conductor AARON COPLAND Simple Gifts Scott Rieker, conductor ROBERT SHAW & Blow the Man Down Scott Rieker, conductor ALICE PARKER Da’Jon James, soloist Daniel Newman-Lessler, soloist David Massatt, soloist ROBERT SHAW & Vive L’Amour Da’Jon James, conductor ALICE PARKER Stephan Pellisier, soloist Ivan Tsung, soloist Luke Can Lant, soloist JOHN FARMER Fair Phyllis Scott Rieker, conductor AARON COPLAND The Dodger Ernest H. Harrison, conductor Chung Ming Zen, soloist Daniel Newman-Lessler, soloist Stephan Pellissier, soloist PAUL BASLER Sing to the Lord Ernest H. -

Les Pages Sur Les Festivals D'été

festivalsSummer d’été Une pléiade de festivals de musique classique se disputent chaque été les faveurs des mélomanes. Le plaisir des yeux y rejoint celui des oreilles, les sites étant souvent splendides et totalement dépaysants. La Scena en brosse, ce mois-ci, un portrait pastoral. A growing number of festivals appeal to classical music lovers. They aim to please their patrons’ ears, but also they strive to delight their eyes, being located in bucolic pastures. This month, La Scena attempts to capture their unique appeal. 3 2pm. StAC. Ensemble vocal Joseph-François- über die Folie d’Espagne, Wq. 118/9, H.263 JULY Perrault; Oakville Children’s Choir; Academic (1778); Mozart: Fantaisie in C minor, K.V. 475 12 20h. EcLER. $10-22. Chausson: Quatuor; Brahms: Choir of Adam Mickiewicz University; Bach (1785); 9 Variationen über ein Menuett von Quatuor #3 en sol mineur. Quatuor Kandinsky Children’s Chorus of Scarborough; Prince of Duport, K.V. 573 (1789); Haydn: Variations in F 13 20h. ÉNDVis. $10-22. Piazzolla: “Four for Tango”; Wales Collegiate Chamber Choir; Choral Altivoz minor, Hob. xvii/6 (1793); Beethoven: 6 Castonguay-Prévost-Michaud: “Redemptio” 3 8pm. A&CC. Cantare-Cantilena Ensemble; Young Variations, op.34 (1802). Cynthia Millman-Floyd, (poème Serge-Patrice Thibodeau); Dvorak: Voices of Melbourne; Daughter of the Baltic fortepiano “Cypresses” #6 10 5 12; Chostakovich: 2 Pieces 3 8pm. GowC. St. John’s Choir; Scunthorpe Co- 3 8pm. DAC Sir James Dunn Theatre. $20-25. Guy: for String Quartet; Reinberger: Nonet op.139. Operative Junior Choir; Amabile Boys Choir Nasca Lines. Upstream Orchestra; Barry Guy, bass Quatuor Arthur-LeBlanc; Eric Lagacé, contre- 4 8pm. -

National Conference Performing Choirs

National Conference Performing Choirs 20152015 ACDA FestivalFestival ChoirChoir UniversityUniversity ofof Utah A Cappella Choir Thursday 8:00 pm - 9:45 pm Abravanel Hall (Blue Track) Friday 8:00 pm - 9:45 pm Abravanel Hall (Gold Track) The 2015 ACDA Festival Choir includes the Utah Sym- phony Chorus, Utah Chamber Artists, the University of Utah Chamber Choir, and the University of Utah A Cappella Choir conducted by Barlow Bradford. The Utah Symphony is con- ducted by Thierry Fischer. Founded in 1962, the A Cappella Choir offers singers the opportunity to perform works for larger choirs and to fi ne- tune the art of choral singing through exposure to music from Utah Chamber Artists the Renaissance through the twenty-fi rst century. Choir mem- bers hone musicianship skills such as rhythm, sight-reading, and the understanding of complex scores. They develop an understanding of the intricacies of vocal production, includ- ing pitch, and how to blend individual voices together into a unifi ed, beautiful sound. In recent years, the A Cappella Choir has become a standard of excellence in student singing in the State of Utah. Last fall, they sang Mozart’s Trinity Mass with the Utah Symphony and the Utah Symphony Chorus under the direction of Thierry Fischer. This renewed a tradition of collaboration between the choirs of the University of Utah and the Utah Symphony, and their outstanding performance resulted in invitations for return engagements in 2015. Utah Chamber Artists was established in 1991 by Barlow University of Utah Chamber Choir Bradford and James Lee Sorenson. The ensemble comprises forty singers and forty players who create a balance and so- nority rarely found in a combined choir and orchestra. -

The Capital Beat Sat-Sun 11:00-17:00 Tickets €0/5.50/8 Virgin Oil CO

26 15 – 21 MARCH 2012 WHERE TO GO HELSINKI TIMES COMPILED BY ANNA-MAIJA LAPPI The retrospective exhibition pre- sents Laine’s paintings from the mid-1980s to the present. Kunsthalle Helsinki Nervanderinkatu 3 SANTTU SÄRKÄS Tue, Thu, Fri 11:00-18:00 Wed 11:00-20:00 The Capital Beat Sat-Sun 11:00-17:00 Tickets €0/5.50/8 Virgin Oil CO. will fill with warmth and energy when the bril- www.taidehalli.fi liant Finnish eight-piece music machine The Capital Beat step on stage on Saturday 17 March. Their music is an exciting mix Until Sun 29 April of ska, reggae and soul that evokes memories of older Jamaican Carl Larsson: In Search of the Good Life sounds but with a fresh and new twist. Exhibition of one of Sweden’s most The band was formed in the summer of 2007, and their debut al- beloved artists includes over a hun- bum, A Greater Fire (2009), was well-received by both critics and dred paintings, and it also presents fans. With their second album, On The Midnight Wire (2011), the Carl and Karin Larsson as designers of furniture and art handicrafts. band took a step in a more reggae direction, and some new spice Ateneum, Kaivokatu 2 was brought to the music by accordions, flutes and strings. The Tue-Fri 10:00-18:00 second album, mixed by producer Bommitommi, also contains ap- Wed, Thu 10:00-20:00 pearances by respected reggae/hip hop/soul musicians such as Sat-Sun 11:00-17:00 Puppa J and Tommy Lindgren from Don Johnson Big Band. -

Web Publications 2005:6

WEB PUBLICATIONS 2005:6 Writers Arts and Culture in Helsinki City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Web publications 2005:6 Aarniokoski Riitta ● Finnish National Gallery, Kiasma Theatre Editorial group ● Askelo Sini City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Statistics and Information Services Chairman: Leila Lankinen, Acting Information Manager Berndtson Maija ● Helsinki City Library Sini Askelo, Senior Statistician; Timo Cantell, Senior Researcher; Marianna Kajantie, Director, City of Helsinki Cultural Office; Vesa Keskinen, Researcher; Cantell Timo ● City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Urban Research Päivi Selander, Project Researcher; Timo Äikäs, Researcher Fontell Klas ● Helsinki City Art Museum Hahtomaa Kikka ● City of Helsinki Cultural Office, Annantalo Arts Centre Graphic design: Olli Turunen | Tovia Design Oy Heimonen Leila ● City of Helsinki Cultural Office, Annantalo Arts Centre Statistics: Sirkka Koski and Annikki Järvinen Hellman Tuomas ● Bachelor of Arts Liaison with printers: Tarja Sundström ● Helminen Martti City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Helsinki City Archives Translation: Magnus Gräsbäck Ilonen Pia ● Talli Architects Language revision: Roger Munn, Bachelor of Arts (hons.) Karjalainen Marketta ● Helsingin Uutiset Enquiries Keskinen Vesa ● City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Urban Research City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Statistics and Information Service Kulonpalo Jussi ● University of Helsinki, Department of Social Policy Address: Aleksanterinkatu 16 –18, 00170 Helsinki P.O. Box 5520 , FIN-00099 City of Helsinki ● Laita Piia Finnish National Gallery, Kiasma Timo Äikäs, + tel. 358 9 169 3184, [email protected]. Lankinen Leila ● City of Helsinki Urban Facts, Statistics and Information Services Sini Askelo, tel. + 358 9 169 3180, [email protected]. Leila Lankinen, tel. + 358 9169 3190, [email protected] Lehtonen Kimmo ● Lasipalatsi Media Centre Lindstedt Johanna ● City of Helsinki Cultural Office, Annantalo Arts Centre Orders Niemi Irmeli ● City of Helsinki Cultural Office, Malmi House Tel. -

TMS 3-1 Pages Couleurs

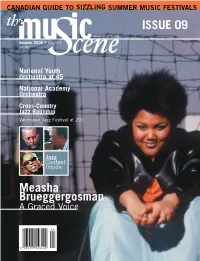

TMS3-4cover.5 2005-06-07 11:10 Page 1 CANADIAN GUIDE TO SIZZLING SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVALS ISSUE 09 www.scena.org Summer 2005 • Vol. 3.4 $4.95 National Youth Orchestra at 45 National Academy Orchestra Cross-Country Jazz Roundup Vancouver Jazz Festival at 20! Jazz Contest Inside Measha Brueggergosman A Graced Voice 0 4 0 0 6 5 3 8 5 0 4 6 4 4 9 TMS3-4 glossy 2005-06-06 09:14 Page 2 QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 5 00 2 N I L O I V S. KHACHATRYAN with G. VARGA and the Belgian National Orchestra © Bruno Vessié 1st Prize Sergey KHACHATRYAN 2nd Prize Yossif IVANOV 3rd Prize Sophia JAFFÉ 4th Prize Saeka MATSUYAMA 5th Prize Mikhail OVRUTSKY 6th Prize Hyuk Joo KWUN Non-ranked laureates Alena BAEVA Andreas JANKE Keisuke OKAZAKI Antal SZALAI Kyoko YONEMOTO Dan ZHU Grand Prize of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition for Composers 2004: Javier TORRES MALDONADO Finalists Composition 2004: Kee-Yong CHONG, Paolo MARCHETTINI, Alexander MUNO & Myung-hoon PAK Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth Competition for Belgian Composers 2004: Hans SLUIJS WWW.QEIMC.BE QUEEN ELISABETH INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION OF BELGIUM INFO: RUE AUX LAINES 20, B-1000 BRUSSELS (BELGIUM) TEL : +32 2 213 40 50 - FAX : +32 2 514 32 97 - [email protected] SRI_MusicScene 2005-06-06 10:20 Page 3 NEW RELEASES from the WORLD’S BEST LABELS Mahler Symphony No.9, Bach Cantatas for the feast San Francisco Symphony of St. John the Baptist Mendelssohn String Quartets, Orchestra, the Eroica Quartet Michael Tilson Thomas une 2005 marks the beginning of ATMA’s conducting. -

Visitors Guide

ENGLISH VISITORS GUIDE VISIT HELSINKI.FI INCLUDES MAP Welcome to Helsinki! Helsinki is a modern and cosmopolitan city, the most international travel des- tination in Finland and home to around 600,000 residents. Helsinki offers a wide range of experiences throughout the year in the form of over 3000 events, a majestic maritime setting, classic and contemporary Finnish design, a vibrant food culture, fascinating neighbourhoods, legendary architecture, a full palette of museums and culture, great shopping opportunities and a lively nightlife. Helsinki City Tourism Brochure “Helsinki – Visitors Guide 2015” Published and produced by Helsinki Marketing Ltd | Translated into English by Crockford Communications | Design and layout by Helsinki Marketing Ltd | Main text by Helsinki Marketing Ltd | Text for theme spreads and HEL YEAH sections by Heidi Kalmari/Matkailulehti Mondo | Printed in Finland by Forssa Print | Printed on Multiart Silk 130g and Novapress Silk 60g | Photos by Jussi Hellsten ”HELSINKI365.COM”, Visit Finland Material Bank | ISBN 978-952-272-756-5 (print), 978-952-272-757-2 (web) This brochure includes commercial advertising. The infor- mation within this brochure was updated in autumn 2014. The publisher is not responsible for possible changes or for the accuracy of contact information, opening times, prices or other related information mentioned in this brochure. CONTENTS Sights & tours 4 Design & architecture 24 Maritime attractions 30 Culture 40 Events 46 Helsinki for kids 52 Food culture & nightlife 60 Shopping 70 Wellness & exercise 76 Outside Helsinki 83 Useful information 89 Public transport 94 Map 96 SEE NEW WALKING ROUTES ON MAP 96-97 FOLLow US! TWITTER - TWITTER.COM/VISITHELSINKI 3 HELSINKI MOMENTS The steps leading up to Helsinki Cathedral are one of the best places to get a sense of this city’s unique atmosphere. -

100 Suomalaista Sävelmää Ja Sanoitusta

SATA SUOMALAISTA SÄVELMÄÄ JA SANOITUSTA Mikä on mielestäsi itsenäisyyden ajan ikimuistoisin suomalainen kevyen musiikin sävellys ja sanoitus, kysyy lauluyhtye Rajaton? Lauluyhtye Rajaton julkaisee syksyllä 2017 levyn, jonka kappaleet yleisö äänestää 31.1.2017 mennessä seuraavien, eri vuosikymmeniltä olevien kappaleiden joukosta. 1920 - 1940 -luvut Ture Ara: Emma 1929 Sävel TRAD, Sanat SIIKANIEMI WÄINÖ Matti Jurva: Ievan polkka 1937, Sävel JURVA MATTI, Sanat KETTUNEN EINO Georg Malmsten: Väliaikainen 1938, Sävel JURVA MATTI, Sanat PEKKARINEN TATU Viljo Vesterinen: Säkkijärven polkka 1939, Sävel TRAD Sovitus VESTERINEN VILJO Leif Wager: Romanssi 1943, Sävel FOUGSTEDT NILS-ERIC, Sanat HIRVISEPPÄ REINO Henry Theel: Liljankukka 1945, Sävel KÄRKI TOIVO, Sanat MUSTONEN KERTTU Tapio Rautavaara: Päivänsäde ja menninkäinen 1949, Sävel /Sanat HELISMAA REINO Eero Väre: Kultainen nuoruus 1949, Sävel LINNA KULLERVO, Sanat KULLERVO 1950 - 1960 -luvut Olavi Virta: Täysikuu 1953, Sävel PUNTA PEDRO DE, Sanat ITÄ ORVOKKI Metro-tytöt: Hiljainen kylätie 1953, Sävel KÄRKI TOIVO, Sanat HELISMAA REINO Annikki Tähti: Muistatko Monrepos'n 1955, Sävel LINDSTRÖM ERIK, Sanat RUNNE AILI Helena Siltala: Ranskalaiset korot 1959, Sävel LINDSTRÖM ERIK, Sanat HILLEVI Laila Kinnunen: Valoa ikkunassa 1961, Sävel HURME EINO, Sanat SAUKKI Reijo Taipale: Satumaa 1962 Sävel/Sanat MONONEN UNTO www.vahvike.fi Kari Kuuva: Tango pelargonia 1964 Sävel/Sanat KUUVA KARI Katri Helena: Puhelinlangat laulaa 1964, Sävel VIHERLUOTO PENTTI , Sanat ETELÄ HARRY Tamara Lund: Sinun omasi 1965, -

Finnish Dance in Focus 2020-2021

2020–2021 P 2 FINNISH DANCE IN FOCUS 2020–2021 EDITORIAL CONTENTS FINNISH DANCE IN FOCUS 2020–2021 P 3 Dance artists travelled to the Arctic Ocean to shoot a film. © Lumikinos FINNISH DANCE IN FOCUS 2020–2021 \ VOLUME TWENTY-TWO DANCE AS A CREATIVE Production © Publisher: Dance Info Finland FORM OF ACTIVISM 12–15 Lennart Tallberginkatu 1 C/93, 00180 Helsinki Tel. +358 (0)9 6121 812 Laberenz [email protected] This year, we have found ourselves in a global situation so serious that artists cannot 30–33 www.danceinfo.fi simply sit back and ignore it. In this edition, dance artists tell us about how they are Editor-in-chief: Sanna Rekola drawing attention through their work to the environmental and human emergency [email protected] we are facing. Artists have a need to make their audiences think, to create a sense of Editor: Sanna Kangasluoma kinship, and to light sparks of hope. © [email protected] But what can dance do in the face of the world’s major problems? And is it even Petri Editorial board: Riitta Aittokallio, Sanna artists’ place to step in? \ Tuohimaa Kangasluoma, Anni Leino, Katarina Lindholm, Educating the audience might not seem like the most obvious way for art to get Fern Minna Luukko, Sanna Rekola the discussion going about important topics and raise awareness – so how can art Orchestra’s make a difference? Because we all want to have an impact and communicate to make plant jams Writers: Ida Henritius, Sanna Kangasluoma, the world a better place, including through dance.