When There Were Wards: a Series in the Nickel, Houston's Fifth Ward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Yale/New Haven-University of Houston Institute

Historical Overview of Texas Southern University and Its Impact Ozzell Taylor Johnson This curriculum briefly discusses why Texas southern University was established, its funding, and why it should remain an open, independent institution. It explores programs offered at Texas Southern University, and introduces some insight into how the university has survived in spite of the many attempts to merge or close it. The unit also identifies outstanding faculty members and successful graduates and their respective contributions to our community and the world. This curriculum unit may be utilized by History Teachers to teach regular or special education students who are in grades 9-12. I. WHY WAS TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY ESTABLISHED? The state of Texas was still operating under the “separate but equal” education philosophy during the forties when Heman Sweatt, a graduate of Wiley College in Austin, applied for admittance to the University of Texas Law School. He had been accepted by the University of Michigan School of Law, however, he wanted to remain in Texas to study. He was denied admission, thusly, he sued in the 126th District court in Austin. No law school in Texas admitted blacks at that time. In the state of Texas, there were 7,724 lawyers and only 23 were black. Sweatt was denied admission on the basis of the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy vs. Ferguson, and the court determined that the state had six months to set up a law school for blacks. Texas A & M Regents hired two black Houston lawyers to teach law in rented rooms. Sweatt refused to enroll in the “law school,” although the court declared that the arrangement satisfied the “separate but equal” test. -

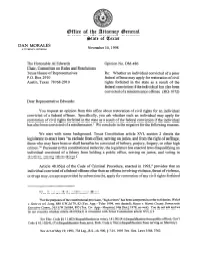

Qmfice of Tfp! !Zlttornep

QMficeof tfp! !zlttornepQhneral Wate of Z!kxae DAN MORALES ATTORNEYOENERAI. November 10, 1998 The Honorable Al Edwards Opinion No. DM-486 Chair, Committee on Rules and Resolutions Texas House of Representatives Re: Whether an individual convicted of a prior P.O. Box 2910 federal offense may apply for restoration of civil Austin, Texas 78768-2910 rights forfeited in the state as a result of the federal conviction if the individual has also been convicted ofamisdemeanor offense (RQ- 1072) Dear Representative Edwards: You request an opinion from this office about restoration of civil rights for an individual convicted of a federal offense. Specifically, you ask whether such an individual may apply for restoration of civil rights forfeited in the state as a result of the federal conviction if the individual has also been convicted of a misdemeanor.’ We conclude in the negative for the following reasons. We start with some background. Texas Constitution article XVI, section 2 directs the legislature to enact laws “to exclude from office, serving on juries, and from the right of suffrage, those who may have been or shall hereafter be convicted of bribery, perjury, forgery, or other high crimes.“z Pursuant to this constitutional authority, the legislature has enacted laws disqualifying an individual convicted of a felony from holding a public office, serving on juries, and voting in elections, among others things.j Article 48.05(a) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, enacted in 1993: provides that an individual convicted of a federal offense other than an offense involving violence, threat ofviolence, or drugs may, except as provided by subsection (b), apply for restoration of any civil rights forfeited ‘You do not specify the misdemeanor offense. -

CITY of HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department A RCHAEOLOGICAL S ITE D ESIGNATION R EPORT SITE NAME: Frost Town Archaeological Site - 80 Spruce Street AGENDA ITEM: III OWNER: Art and Environmental Architecture, Inc. HPO FILE NO: 09AS1 APPLICANT: Kirk Farris DATE ACCEPTED: Sept-09-09 LOCATION: 80 Spruce Street – Frost Town HAHC HEARING: Sept-24-09 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING: Oct-1-09 SITE INFORMATION Lot 5 (being .1284 acres situated at the northwest corner of), Block F, Frost Town Subdivision, SSBB, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site is a vacant tract of land located within the former Frost Town site and has been designated as a State of Texas Archaeological Site. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Archaeological Site Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY Frost Town was first settled in 1836 and would become the first residential suburb of the City of Houston, then-Capitol of the new Republic of Texas. Frost Town was located in a bend on the south bank of Buffalo Bayou approximately ½ mile downriver from the present site of downtown Houston. The 15-acre site was purchased from Augustus and John Allen by Jonathan Benson Frost, a Tennessee native and a recent veteran of the Texas Revolution, who paid $1,500 ($100 per acre) for the land in April 1837. Frost built a house and blacksmith shop on the property, but died shortly after of cholera. His brother, Samuel M. Frost subdivided the 15 acres into eight blocks of 12 lots each, and began to sell lots on July 4, 1838. -

Dei Insider Ete Jun Edition 2021

H ENT DEI INSIDER ETE JUN EDITION 2021 OUR DIVISION INVITES YOU TO CELEBRATE JUNETEENTH VIRTUALLY OR IN-PERSON ORIGINS OF JUNETEENTH Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration that honors the end of slavery in the United States. It marks the day of June 19th, 1865, when federal troops arrived in Texas to take control of the state and guarantee that all slaves be freed. The troops’ arrival came a full 2 ½ years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Slavery would not be abolished completely until the 13th Amendment, which was ratified six months later. Juneteenth is considered the longest-running African American holiday. Although Juneteenth is not a federal holiday, 47 out of 50 states recognize it as a state or ceremonial holiday. Nicknames for this holiday include Emancipation Day, Jubilee Day, and Freedom Day. Learn more Celebrating Juneteenth at UT Southwestern Join UT Southwestern’s African American Employee Business Resource Group (AAE- BRG) on Friday, June 18, 2021 from 12 to 1 p.m. for their virtual event, "A Brief Juneteenth day celebration in Texas, 1900. Discussion of the Historical Significance of Juneteenth,” featuring Dr. Ervin James (Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.) III, Ph.D. of Paul Quinn College. Register here. WHO WE CELEBRATE THE FLAG Juneteenth honors those who were enslaved and The original Juneteenth Flag is a representation recognizes and celebrates the contributions and of the end of slavery in the U.S. This flag was achievements of African Americans. created in 1997 by activist Ben Haith, the founder of the National Juneteenth Celebration Juneteenth has long been celebrated in Texas, even Foundation (NJCF). -

Transportation Texas House of Representatives Interim Report 2000

HOUSE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2000 A REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 77TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE CLYDE ALEXANDER CHAIRMAN COMMITTEE CLERK CHERYL JOURDAN Committee On Transportation November 30, 2000 Clyde Alexander P.O. Box 2910 Chairman Austin, Texas 78768-2910 The Honorable James E. "Pete" Laney Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Members of the Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Committee on Transportation of the Seventy-Sixth Legislature hereby submits its interim report including recommendations and drafted legislation for consideration by the Seventy-Seventh Legislature. Respectfully submitted, Clyde Alexander, Chairman Bill Siebert, Vice Chairman Yvonne Davis Al Edwards Peggy Hamric Judy Hawley Fred Hill Rick Noriega D.R. “Tom” Uher Clyde Alexander Chairman Members: Bill Siebert, Vice-Chairman; Yvonne Davis; Al Edwards; Peggy Hamric; Judy Hawley; Fred Hill; Rick Noriega; D.R. “Tom” Uher Clyde Alexander Chairman Members: Bill Siebert, Vice-Chairman; Yvonne Davis; Al Edwards; Peggy Hamric; Judy Hawley; Fred Hill; Rick Noriega; D.R. “Tom” Uher TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................1 INTERIM STUDY CHARGES ....................................................2 Study ways the state and counties can ensure a safe, adequately funded county road and bridge system consistent with encouraging commerce and economic growth. .......3 Study the advantages and disadvantages of a graduated driver's license program, including the experience of states that have recently enacted such programs. .............11 Examine highway funding issues in light of the combined impact of rapid transportation growth and increased NAFTA traffic. Monitor state and federal developments related to funding and planning of NAFTA corridors. -

HVS Market Intelligence Report: Houston, Texas

HVS Market Intelligence Report: Houston, Texas December 11, 2007 By Shannon L. Sampson Houston is perpetually reinventing itself. No longer typeset as the “Energy Capital of the Summary World,” the city’s economy has diversified greatly over the past two decades, with growth outpacing national standards. Natural resource exploration and production still play a hefty Once thought of as a big oil role in Houston, to be sure, especially following the recent resurgence of the energy markets. town, Houston’s vast array But another of Houston’s nicknames is “Space City,” referring to NASA’s famous Manned‐ of new developments are Space flight and Mission Control Centers—and major new office and retail developments, the taking off throughout "Space expansion of the convention center, and the renaissance of the downtown area encourage a broader City." interpretation of this moniker. Once susceptible to a homogeneous energy industry, Houston now boasts a diversified economy that can withstand major economic interruptions. This article explores how Houston is using Comments its “space” in vastly diverse ways—from skyscrapers to boutique hotels, from the Museum District to the port, from its stadiums to its world‐class shopping mall—and how hotel properties fare on the grid. During the third quarter of 2007, Houston’s office space occupancy reached nearly 90% of an inventory spanning roughly 180 million square feet, with approximately 1.3 million square feet positively absorbed. An additional 24 buildings currently under construction will add another four million square feet of Class A space to FILED UNDER Houston’s office market.[1] Significant growth in office construction is occurring in the western submarkets of CATEGORIES Westchase and the Energy Corridor, and two office towers are slated to begin construction in 2008 within the Central Business District, further pillaring the third‐largest skyline in the United States. -

East End Historical Markers Driving Tour

East End Historical Markers Driving Tour Compiled by Will Howard Harris County Historical Commission, Heritage Tourism Chair 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS DOWNTOWN – Harris County NORTHWEST CORNER – German Texans Frost Town 512 McKee: MKR Frost Town 1900 Runnels: MKR Barrio El Alacran 2115 Runnels: Mkr: Myers-Spalti Manufacturing Plant (now Marquis Downtown Lofts) NEAR NAVIGATION – Faith and Fate 2405 Navigation: Mkr: Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church 2407 Navigation: Mkr in cemetery: Samuel Paschall BRADY LAND: Magnolias and Mexican Americans MKR Quiosco, Mkr for Park [MKR: Constitution Bend] [Houston’s Deepwater Port] 75th & 76th: 1400 @ J &K, I: De Zavala Park and MKR 76th St 907 @ Ave J: Mkr: Magnolia Park [MKR: League of United Latin American Citizens, Chapter 60] Ave F: 7301: MKR Magnolia Park City Hall / Central Fire Station #20 OLD TIME HARRISBURG 215 Medina: MKR Asbury Memorial United Methodist Church 710 Medina @ Erath: Mkr: Holy Cross Mission (Episcopal) 614 Broadway @ E Elm, sw cor: MKR Tod-Milby Home site 8100 East Elm: MKR Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado RR 620 Frio: MKR Jane Briscoe Harris Home site Magnolia 8300 across RR: Mkr, Glendale Cemetery Magnolia 8300, across RR: Mkr, Site of Home of General Sidney Sherman [Texas Army Crossed Buffalo Bayou] [Houston Yacht Club] Broadway 1001 @ Lawndale: at Frost Natl Bk, with MKR “Old Harrisburg” 7800 @ 7700 Bowie: MKR Harrisburg-Jackson Cemetery East End Historical Makers Driving Tour 1 FOREST PARK CEMETERY [Clinton @ Wayside: Mkr: Thomas H. Ball, Jr.] [Otherwise Mkr: Sam (Lighnin’) Hopkins] THE SOUTHERN RIM: Country Club and Eastwood 7250 Harrisburg: MKR Immaculate Conception Catholic Church Brookside Dr. -

Two Paths to Greatness: Elvin Hayes and by Katherine Lopez

Two Paths to Greatness: Elvin Hayes and By Katherine Lopez he City of Houston had a humble of athletic glory and personal fulfi llment. attention to it. These are their stories. Tbeginning as the Allen brothers, two These individuals, although numeri- Elvin Hayes was born in the small entrepreneurs willing to pedal land, began cally small in comparison to the overall Louisiana town of Rayville in 1945. It, like selling plots near the Texas coast that many number of immigrants entering the city, most other Jim Crow cities of the time, considered worthless in 1836. Although have disproportionately contributed to presented few opportunities for its non- it initially struggled, bountiful opportu- Houston’s growth for they became publi- white residents and little hope of escape. nities—such as the building of the Port cized representations of the success to be Despite that, Hayes was determined to of Houston, the explosion of the space acquired within the city. While numerous fi nd a “better life out there beyond Rayville industry, and the liberal concentration of transplanted athletes have graced the courts and north Louisiana” and would “fi nd 1 natural oil and gas reserves—presented and fi elds over the last century and history some kind of vehicle” to take him away. individuals with the potential for personal could highlight several of them who trans- His journey out began when, in the eighth and fi nancial advancement and soon formed into proponents of Houston, two grade, Hayes picked up a basketball and Houston was transformed from a small individuals in particular jump out from the began developing the skills that would lift frontier town into a thriving metropolis. -

A Guide to Researching Your Neighborhood History

A Guide to Researching Your Neighborhood History Prepared by the Neighborhood Histories Committee of the Houston History Association Contributors Betty Trapp Chapman Jo Collier Dick Dickerson Diana DuCroz MJ Figard Marks Hinton Penny Jones Robert Marcom Carol McDavid Randy Pace Gail Rosenthal Debra Blacklock Sloan Courtney Spillane Pam Young © Houston History Association, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. GETTING S TARTED ....................................................................................... 5 Why Do a Neighborhood History Project Now? ..................................................................5 Some Ideas for a Neighborhood History Project ..................................................................5 Who can do a Neighborhood History Project? .....................................................................5 How to Get Started..............................................................................................................5 Historical Resources............................................................................................................6 RESEARCH T OOLS AND TIPS FOR USING L OCAL RESOURCES ................................. 7 Introduction.........................................................................................................................7 Getting Started ....................................................................................................................7 Using -

Texas Legislative Black Caucus 1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172

Texas Legislative Black Caucus 1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172 Chairman, About Us Sylvester Turner The Texas Legislative Black Caucus was formed in 1973 and consisted of eight members. These founding District 139- Houston members were: Anthony Hall, Mickey Leland, Senfronia Thompson, Craig Washington, Sam Hudson, Eddie 1st Vice Chair Bernice Johnson, Paul Ragsdale, and G.J. Sutton. The Texas Legislative Black Caucus is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, Ruth McClendon non-partisan organization composed of 15 members of the Texas House of Representatives committed to District 120- San Antonio addressing the issues African Americans face across the state of Texas. Rep. Sylvester Turner is Chairman of the Texas Legislative Black Caucus for the 81st Session. State Senators Rodney Ellis and Royce West, the two 2nd Vice Chair Marc Veasey members who comprise the Senate Legislative Black Caucus, are included in every Caucus initiative as well. District 95- Fort Worth African American Legislative Summit Secretary In April 2009, the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, in conjunction with Prairie View A&M University and Texas Helen Giddings Southern University, hosted the 10th African American Legislative Summit in Austin at the Texas Capitol. District 109- Dallas Themed “The Momentum of Change,” the 2009 summit examined issues that impact African American Treasurer communities in Texas on a grassroots level and provided a forum for information-sharing and dialogue. The next Alma Allen African American Legislative Summit is set for February 28th – March 1st, 2011. District 131- Houston Recent Initiatives Parliamentarian Joe Deshotel Institute for Critical Urban Policy and Department of African & African Diaspora Studies District 22- Beaumont Chairman Turner spearheaded an effort with The University of Texas at Austin to establish the Institute for Critical Urban Policy and Black Studies Department, which will both launch in the fall of General Counsel 2010.