Interim Report to the 82Nd Texas Legislature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Yale/New Haven-University of Houston Institute

Historical Overview of Texas Southern University and Its Impact Ozzell Taylor Johnson This curriculum briefly discusses why Texas southern University was established, its funding, and why it should remain an open, independent institution. It explores programs offered at Texas Southern University, and introduces some insight into how the university has survived in spite of the many attempts to merge or close it. The unit also identifies outstanding faculty members and successful graduates and their respective contributions to our community and the world. This curriculum unit may be utilized by History Teachers to teach regular or special education students who are in grades 9-12. I. WHY WAS TEXAS SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY ESTABLISHED? The state of Texas was still operating under the “separate but equal” education philosophy during the forties when Heman Sweatt, a graduate of Wiley College in Austin, applied for admittance to the University of Texas Law School. He had been accepted by the University of Michigan School of Law, however, he wanted to remain in Texas to study. He was denied admission, thusly, he sued in the 126th District court in Austin. No law school in Texas admitted blacks at that time. In the state of Texas, there were 7,724 lawyers and only 23 were black. Sweatt was denied admission on the basis of the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy vs. Ferguson, and the court determined that the state had six months to set up a law school for blacks. Texas A & M Regents hired two black Houston lawyers to teach law in rented rooms. Sweatt refused to enroll in the “law school,” although the court declared that the arrangement satisfied the “separate but equal” test. -

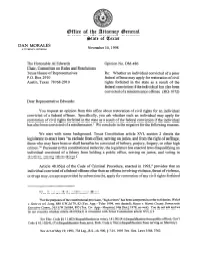

Qmfice of Tfp! !Zlttornep

QMficeof tfp! !zlttornepQhneral Wate of Z!kxae DAN MORALES ATTORNEYOENERAI. November 10, 1998 The Honorable Al Edwards Opinion No. DM-486 Chair, Committee on Rules and Resolutions Texas House of Representatives Re: Whether an individual convicted of a prior P.O. Box 2910 federal offense may apply for restoration of civil Austin, Texas 78768-2910 rights forfeited in the state as a result of the federal conviction if the individual has also been convicted ofamisdemeanor offense (RQ- 1072) Dear Representative Edwards: You request an opinion from this office about restoration of civil rights for an individual convicted of a federal offense. Specifically, you ask whether such an individual may apply for restoration of civil rights forfeited in the state as a result of the federal conviction if the individual has also been convicted of a misdemeanor.’ We conclude in the negative for the following reasons. We start with some background. Texas Constitution article XVI, section 2 directs the legislature to enact laws “to exclude from office, serving on juries, and from the right of suffrage, those who may have been or shall hereafter be convicted of bribery, perjury, forgery, or other high crimes.“z Pursuant to this constitutional authority, the legislature has enacted laws disqualifying an individual convicted of a felony from holding a public office, serving on juries, and voting in elections, among others things.j Article 48.05(a) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, enacted in 1993: provides that an individual convicted of a federal offense other than an offense involving violence, threat ofviolence, or drugs may, except as provided by subsection (b), apply for restoration of any civil rights forfeited ‘You do not specify the misdemeanor offense. -

Dei Insider Ete Jun Edition 2021

H ENT DEI INSIDER ETE JUN EDITION 2021 OUR DIVISION INVITES YOU TO CELEBRATE JUNETEENTH VIRTUALLY OR IN-PERSON ORIGINS OF JUNETEENTH Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration that honors the end of slavery in the United States. It marks the day of June 19th, 1865, when federal troops arrived in Texas to take control of the state and guarantee that all slaves be freed. The troops’ arrival came a full 2 ½ years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Slavery would not be abolished completely until the 13th Amendment, which was ratified six months later. Juneteenth is considered the longest-running African American holiday. Although Juneteenth is not a federal holiday, 47 out of 50 states recognize it as a state or ceremonial holiday. Nicknames for this holiday include Emancipation Day, Jubilee Day, and Freedom Day. Learn more Celebrating Juneteenth at UT Southwestern Join UT Southwestern’s African American Employee Business Resource Group (AAE- BRG) on Friday, June 18, 2021 from 12 to 1 p.m. for their virtual event, "A Brief Juneteenth day celebration in Texas, 1900. Discussion of the Historical Significance of Juneteenth,” featuring Dr. Ervin James (Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.) III, Ph.D. of Paul Quinn College. Register here. WHO WE CELEBRATE THE FLAG Juneteenth honors those who were enslaved and The original Juneteenth Flag is a representation recognizes and celebrates the contributions and of the end of slavery in the U.S. This flag was achievements of African Americans. created in 1997 by activist Ben Haith, the founder of the National Juneteenth Celebration Juneteenth has long been celebrated in Texas, even Foundation (NJCF). -

Transportation Texas House of Representatives Interim Report 2000

HOUSE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERIM REPORT 2000 A REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 77TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE CLYDE ALEXANDER CHAIRMAN COMMITTEE CLERK CHERYL JOURDAN Committee On Transportation November 30, 2000 Clyde Alexander P.O. Box 2910 Chairman Austin, Texas 78768-2910 The Honorable James E. "Pete" Laney Speaker, Texas House of Representatives Members of the Texas House of Representatives Texas State Capitol, Rm. 2W.13 Austin, Texas 78701 Dear Mr. Speaker and Fellow Members: The Committee on Transportation of the Seventy-Sixth Legislature hereby submits its interim report including recommendations and drafted legislation for consideration by the Seventy-Seventh Legislature. Respectfully submitted, Clyde Alexander, Chairman Bill Siebert, Vice Chairman Yvonne Davis Al Edwards Peggy Hamric Judy Hawley Fred Hill Rick Noriega D.R. “Tom” Uher Clyde Alexander Chairman Members: Bill Siebert, Vice-Chairman; Yvonne Davis; Al Edwards; Peggy Hamric; Judy Hawley; Fred Hill; Rick Noriega; D.R. “Tom” Uher Clyde Alexander Chairman Members: Bill Siebert, Vice-Chairman; Yvonne Davis; Al Edwards; Peggy Hamric; Judy Hawley; Fred Hill; Rick Noriega; D.R. “Tom” Uher TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................1 INTERIM STUDY CHARGES ....................................................2 Study ways the state and counties can ensure a safe, adequately funded county road and bridge system consistent with encouraging commerce and economic growth. .......3 Study the advantages and disadvantages of a graduated driver's license program, including the experience of states that have recently enacted such programs. .............11 Examine highway funding issues in light of the combined impact of rapid transportation growth and increased NAFTA traffic. Monitor state and federal developments related to funding and planning of NAFTA corridors. -

Texas Legislative Black Caucus 1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172

Texas Legislative Black Caucus 1108 Lavaca St, Suite 110-PMB 171, Austin, TX 78701-2172 Chairman, About Us Sylvester Turner The Texas Legislative Black Caucus was formed in 1973 and consisted of eight members. These founding District 139- Houston members were: Anthony Hall, Mickey Leland, Senfronia Thompson, Craig Washington, Sam Hudson, Eddie 1st Vice Chair Bernice Johnson, Paul Ragsdale, and G.J. Sutton. The Texas Legislative Black Caucus is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, Ruth McClendon non-partisan organization composed of 15 members of the Texas House of Representatives committed to District 120- San Antonio addressing the issues African Americans face across the state of Texas. Rep. Sylvester Turner is Chairman of the Texas Legislative Black Caucus for the 81st Session. State Senators Rodney Ellis and Royce West, the two 2nd Vice Chair Marc Veasey members who comprise the Senate Legislative Black Caucus, are included in every Caucus initiative as well. District 95- Fort Worth African American Legislative Summit Secretary In April 2009, the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, in conjunction with Prairie View A&M University and Texas Helen Giddings Southern University, hosted the 10th African American Legislative Summit in Austin at the Texas Capitol. District 109- Dallas Themed “The Momentum of Change,” the 2009 summit examined issues that impact African American Treasurer communities in Texas on a grassroots level and provided a forum for information-sharing and dialogue. The next Alma Allen African American Legislative Summit is set for February 28th – March 1st, 2011. District 131- Houston Recent Initiatives Parliamentarian Joe Deshotel Institute for Critical Urban Policy and Department of African & African Diaspora Studies District 22- Beaumont Chairman Turner spearheaded an effort with The University of Texas at Austin to establish the Institute for Critical Urban Policy and Black Studies Department, which will both launch in the fall of General Counsel 2010. -

When There Were Wards: a Series in the Nickel, Houston's Fifth Ward

When There Were Wards: A Series in The Nickel , houston’s fifth ward By Patricia Pando Jensen were busy commercial streets, home to every- And stay off Lyons Avenue street thing from drugstores to lumberyards and repair garages. And don’t go down on Jensen nowhere Predominately African American, blue-collar and middle- 1 class neighborhoods offered stability and traditional values. Because you’re living on luck and a prayer. In one such neighborhood, a recent graduate of Phillis eldon “Juke Boy” Bonner, performing at Club 44 Wheatley High School and Texas Southern University, Wsometime in the late 1960s not far from that notorious where she had been a national-champion debater, looked intersection, had the facts straight (albeit incomplete) about forward to attending law school in Boston. Nearby, a teen- Houston’s Fifth Ward neighborhood, sometimes known as age boy prepared to enter Wheatley where he would become “Pearl Harbor, the Times Square of the Bloody Fifth” for a sports star before studying pharmacy at Texas Southern. the high possibility that someone in the wrong place at the Another Fifth Ward teen saved himself from slipping into wrong time would meet with a sudden demise. Many musi- a life of crime by taking up boxing; he was good—he won a cians were willing to take that nighttime risk just for the gold medal at the 1968 Olympics. Barbara Jordan, Mickey chance to perform at Club 44 or at Club Matinee, premier Leland, and George Foreman always proudly recalled their gathering spots. Other great musicians—Illinois Jacquet, Fifth roots.3 “Gatemouth” Brown, Arnett Cobb, Goree Carter, “Light- When Houston first established political wards, it desig- nin’” Hopkins (usually associated with the Third Ward), nated only four; the Fifth Ward did not exist. -

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2004

TEXAS FACT BOOK CONTENTS III LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD SEVENTY-EIGHTH TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2003 – 2004 DAVID DEWHURST, CO-CHAIR Austin, Lieutenant Governor TOM CRADDICK, CO-CHAIR Representative District 82, Midland Speaker of the House of Representatives TEEL BIVINS Senatorial District 31, Amarillo Chair, Committee on Finance BILL RATLIFF Senatorial District 1, Mt. Pleasant CHRIS HARRIS Senatorial District 9, Arlington JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston TALMADGE HEFLIN Representative District 149, Houston Chair, House Committee on Appropriations RON WILSON Representative District 131, Houston Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means FRED HILL Representative District 112, Richardson VILMA LUNA Representative District 33, Corpus Christi JOHN KEEL, Director TEXAS FACT BOOK CONTENTS I II CONTENTS TEXAS FACT BOOK THE TRAVIS LETTER FROM THE ALAMO Commandancy of the Alamo–– Bejar, Feby. 24, 1836 To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World –– Fellow citizens & compatriots –– I am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna –– I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man –– The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken –– I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls –– I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch –– The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. -

June Newsletter

Gay pride or LGBT pride is the promotion of the self-affirmation, dignity, equality, and increased visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people as a social group. Pride, as opposed to shame and social stigma, is the predominant outlook that bolsters most LGBT rights movements. Pride has lent its name to LGBT-themed organizations, institutes, foundations, book titles, periodicals, a cable TV station, and the Pride Library. The Stonewall Inn, site of the June 1969 Stonewall riots, the cradle of the modern LGBT rights movement, and an icon of queer culture, is adorned with rainbow pride flags. LGBT Pride Month occurs in the United States to commemorate the Stonewall riots, which occurred at the end of June 1969. As a result, many pride events are held during this month to recognize the impact LGBT people have had in the world. Three presidents of the United States have officially declared a pride month. First, President Bill Clinton declared June "Gay & Lesbian Pride Month" in 1999 and 2000. Then from 2009 to 2016, each year he was in office, President Barack Obama declared June LGBT Pride Month. Later, President Joe Biden declared June LGBTQ+ Pride Month in 2021. Donald Trump became the first Republican president to acknowledge LGBT Pride Month in 2019, but he did so through tweeting rather than an official proclamation. Beginning in 2012, Google displayed some LGBT-related search results with different rainbow- colored patterns each year during June. In 2017, Google also included rainbow coloured streets on Google Maps to display Gay Pride marches occurring across the world. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with the Honorable Albert Edwards

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with The Honorable Albert Edwards PERSON Edwards, Albert, 1937- Alternative Names: The Honorable Albert Edwards; Albert Ely Edwards; Life Dates: March 19, 1937- Place of Birth: Houston, Texas, USA Residence: Houston, TX Work: Houston, TX Occupations: State Representative Biographical Note State Representative, Hon. Albert Ely Edwards was born in Houston, Texas on March 19, 1937. Edwards is the sixth child out of the sixteen children born to Reverend E. L. Edwards, Sr. and Josephine Radford Edwards. He graduated from Phyllis Wheatley High Edwards. He graduated from Phyllis Wheatley High School and attended Texas Southern University, earning his B.A. degree in 1966. At the age of forty-one, Edwards entered politics and was elected to the Texas State Legislature from Houston’s House District 146. His first major goal was to ensure the establishment of a holiday that recognized the emancipation of slavery. In 1979, legislation recognizing Juneteenth Day, initiated by Edwards, passed the Texas State Legislature and was signed into law. Juneteenth, also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day, is an annual holiday in fourteen states of the United States. Celebrated on June 19th, it commemorates the announcement of the abolition of slavery in Texas. While serving in the legislature, Edwards also founded his own real estate company. Though deeply involved with local issues, Edwards remained active in many issues outside the Texas State Legislature. In 1983, Edwards was appointed as a member of the board of Operation PUSH. Edwards also served as the Texas State Director of Reverend Jesse Jackson’s two presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988. -

Al Edwards Juneteenth U.S.A. the Mary L. Hawkins Memorial

The Black Bringing it The Church is Back to Lion Black Church King Power Page 3 Page 3 Page 9 ^AlUM^I^Ppportumty News, Inc. ^H ^B ^B ^Hi^ ^^^^^V^H Volume XI, Number XXIV '' 9^0 r t ft 'D a [ [ a s ' 74^ e e kj'ij Taper o f C h o i c e " June 13-June 19, 2002 SERVING PLANO, DALLAS, RICHARDSON, GARLAND, ALLEN, MCKINNEY AND MESQUITE Al Edwards June 19th is known in Juneteenth U.S.A. may places as Juneteenth History of Juneteenth. was deliberately withheld by VCTiat is Juneteenth? Jimeteenth the slave masters to maintain is the oldest known celebration the labor force on the planta of the ending of slavery. Dating tions. And still another, is that On the Homefront: back to 1865, it was on June federal troops actually waited Fran jrac li-JaliF 21, Ik Diin OUna'dlictttr Kdl 19th that the for the slave own tot -AknDdv Md ik TcirUt, BwrMe, No Good. Union soldiers, ers to reap the Vcr> Btd Dff," h]r boi xOtai Mkr MM Mm. »d MMkbfSbcatMtiUwa. Mbnncai>abeMilai led by Major benefits of one B Cenn CoOf^ IViur,« Mik iDd Hirkti Snm General Gordon last cotton har •nrtheficflEadrfDmiitstnMK. ftdM—Mt «ffl h ktM M FridiT u T:%a., Snrd^ H Granger, landed vest before going liMpjiL, Sndqi It t J^A, ad 4Jtp.iB. Tkka CM at Galveston, to Texas to llJIwdUmMdmbriUi SpctUnMiR ndnv for ffoipi if If fif DBit> rof mtnitnuor Texas with news enforce the nan JBfenBiiM, caO iht OCT Bu Offici e C Uj rt- that the war had Ollfc TUi ibm k RceaoMMkd far EHdn «itk tU- Emancipation dm Am ycm nd Ma. -

Thursday, July 22, 2021-3Rd

SENATE JOURNAL EIGHTY-SEVENTH LEGISLATURE Ð FIRST CALLED SESSION AUSTIN, TEXAS PROCEEDINGS THIRD DAY (Thursday, July 22, 2021) The Senate met at 10:00 a.m. pursuant to adjournment and was called to order by the President. The roll was called and the following Senators were present:iiAlvarado, Bettencourt, Birdwell, Blanco, Buckingham, Campbell, Creighton, Eckhardt, Gutierrez, Hall, Hancock, Hinojosa, Huffman, Hughes, Johnson, Kolkhorst, Lucio, MeneÂndez, Miles, Nelson, Nichols, Paxton, Perry, Powell, Schwertner, Seliger, Springer, Taylor, West, Whitmire, Zaffirini. The President announced that a quorum of the Senate was present. Senator Hinojosa offered the invocation as follows: Thank You, Lord, for another blessed day. We pray for Your spiritual protection. We pray that You protect us from evil. We ask that You protect our families, our neighbors, and friends, and bless us all with good health. Lord, we ask for Your divine guidance and wisdom through the many challenges we face today. Provide us the strength, the courage, and protection from every battle we face in our life. Do not let our anger blind us as we make difficult decisions. Look over us and help us settle our differences in peace as we are family, we are friends, and we represent Texas. Every person should be treated with dignity and respect. We are all Your children. We know that one day You will set right all injustices and wrongs. God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things which should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other, living one day at a time, enjoying one moment at a time, accepting hardship as a pathway to peace, taking, as Jesus did, this sinful world as it is, not as we would have it, trusting that You will make all things right if I surrender to Your will, so that I may be reasonably happy in this life and supremely happy with You forever in the next life.