Randomized Controlled Trial of Ondansetron Vs. Prochlorperazine in Adults in the Emergency Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prochlorperazine 5Mg Tablets

Package leaflet: Information for the patient Prochlorperazine 5mg tablets Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this • the person is a child. This is because children may develop unusual face and body medicine, because it contains important information for you. movements (dystonic reactions) • Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. • you are diabetic or have high levels of sugar in your blood (hyperglycaemia). Your doctor • If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. may want to monitor you more closely. • This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to If you are not sure if any of the above apply to you, talk to your doctor or pharmacist before others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same taking Prochlorperazine Tablets. as yours. Other medicines and Prochlorperazine tablets • If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Tell your doctor or pharmacist if you are taking, have recently taken or might take any This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. other medicines. This includes medicines you buy without a prescription, including herbal See section 4. medicines. This is because Prochlorperazine Tablets can affect the way some other medicines work. What is in this leaflet: Also some medicines can affect the way Prochlorperazine Tablets work. 1 What Prochlorperazine tablets are and what they In particular, tell your doctor if you are taking any of the following: • medicines to help you sleep -

Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014

Federal Bureau of Prisons Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Natural History ................................................................................................................................. 2 Special Considerations ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Screening ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening Questions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Further Screening Methods................................................................................................................ 4 4. Diagnosis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Depression: Three Levels of Severity ............................................................................................... 4 Clinical Interview and Documentation of Risk Assessment............................................................... -

Louisiana Fee-For-Service Medicaid Antipsychotics

Louisiana Fee-for-Service Medicaid Antipsychotics The Louisiana Uniform Prescription Drug Prior Authorization Form should be utilized to request: Authorization for non-preferred agents for recipients 6 years of age and older; AND Authorization for all preferred and non-preferred agents for recipients younger than 6 years of age; AND Authorization to exceed maximum daily dose/quantity limit for all ages. See full prescribing information for individual agents for details on the information below: *These agents have Black Box Warnings †These agents are subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) under FDA safety regulations ‡ For long-acting injectable agents, it is required that the previous 60-day period of pharmacy claims show one of the following: Established tolerance to the oral formulation (as evidenced by a paid pharmacy claim for the oral formulation); OR Established therapy with the requested injectable agent (as evidenced by a paid pharmacy claim for the requested injectable agent) NOTE: Diagnosis code requirements apply to both preferred and non-preferred agents (see Table 1). Maximum daily dose edits (see Table 2), quantity limits (see Table 3), and other requirements at Point-of-Sale for select agents in this category may apply to both preferred and non-preferred agents. For additional information, see http://www.lamedicaid.com/provweb1/Pharmacy/pharmacyindex.htm. Oral Antipsychotics – Generic Name (Brand Example) * Amitriptyline/Perphenazine * Aripiprazole ODT; Oral Solution (Abilify®); Tablet (Abilify®) -

Medications to Be Avoided Or Used with Caution in Parkinson's Disease

Medications To Be Avoided Or Used With Caution in Parkinson’s Disease This medication list is not intended to be complete and additional brand names may be found for each medication. Every patient is different and you may need to take one of these medications despite caution against it. Please discuss your particular situation with your physician and do not stop any medication that you are currently taking without first seeking advice from your physician. Most medications should be tapered off and not stopped suddenly. Although you may not be taking these medications at home, one of these medications may be introduced while hospitalized. If a hospitalization is planned, please have your neurologist contact your treating physician in the hospital to advise which medications should be avoided. Medications to be avoided or used with caution in combination with Selegiline HCL (Eldepryl®, Deprenyl®, Zelapar®), Rasagiline (Azilect®) and Safinamide (Xadago®) Medication Type Medication Name Brand Name Narcotics/Analgesics Meperidine Demerol® Tramadol Ultram® Methadone Dolophine® Propoxyphene Darvon® Antidepressants St. John’s Wort Several Brands Muscle Relaxants Cyclobenzaprine Flexeril® Cough Suppressants Dextromethorphan Robitussin® products, other brands — found as an ingredient in various cough and cold medications Decongestants/Stimulants Pseudoephedrine Sudafed® products, other Phenylephrine brands — found as an ingredient Ephedrine in various cold and allergy medications Other medications Linezolid (antibiotic) Zyvox® that inhibit Monoamine oxidase Phenelzine Nardil® Tranylcypromine Parnate® Isocarboxazid Marplan® Note: Additional medications are cautioned against in people taking Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), including other opioids (beyond what is mentioned in the chart above), most classes of antidepressants and other stimulants (beyond what is mentioned in the chart above). -

Stemzine® (Prochlorperazine Maleate) Tablet

AUSTRALIAN PRODUCT INFORMATION – STEMZINE® (PROCHLORPERAZINE MALEATE) TABLET 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINE Prochlorperazine maleate. 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Stemzine contains 5mg prochlorperazine maleate as the active ingredient. Excipients of known effect: wheat starch (gluten). For the full list of excipients, see Section 6.1 List of excipients. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Stemzine 5 mg tablets are off-white to pale cream coloured circular tablets, not more than slightly mottled or specked, one side impressed with 'S' and reverse face plain. 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS Nausea and vomiting due to various causes including migraine; vertigo due to Meniere's syndrome, labyrinthitis and other causes. 4.2 DOSE AND METHOD OF ADMINISTRATION Nausea and vomiting Adults Dosage should be adjusted to suit the response of the individual, beginning with lowest recommended dosage. Oral: 5 or 10 mg two or three times daily. Acute: 20 mg at once, followed, if necessary by 10 mg two hours later. Children (See Section 4.4 Special warnings and precautions for use, Paediatric Use). stem-ccsiv5-piv19-04jun21 Page 1 of 16 If it is considered unavoidable to use prochlorperazine for a child, the dosage is 250 micrograms/kg bodyweight two or three times a day. Prochlorperazine has been associated with dystonic reactions particularly after a cumulative dosage of 500 micrograms/kg. It should therefore be used cautiously in children. Prochlorperazine is not recommended for children weighing less than 10 kg. When treating children, it is recommended that the 5 mg tablets are used. Vertigo and meniere’s disease Adults Oral: 5 to 10 mg three or four times daily. -

207533Orig1s000

( CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 207533Orig1s000 RISK ASSESSMENT and RISK MITIGATION REVIEW(S) Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology Office of Medication Error Prevention and Risk Management Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) Review Date: October 2, 2015 Reviewer(s): Cathy A. Miller, MPH, B.SN Risk Management Analyst Division of Risk Management Team Leader Kimberly Lehrfeld, Pharm.D. Division of Risk Management Acting Deputy Division Reema Mehta, Pharm.D., MPH Director Division of Risk Management Drug Name(s): Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil) extended-release injection Therapeutic Class: Atypical Antipsychotic Dosage and Route: 441 mg/1.6 mL; 662 mg/2.4 mL; 882 mg/3.2mL intramuscular injection Application Type/Number: NDA 207533 Submission Number: ORIG-1 Submission Seq. No. 0000 dated August 22, 2014 Applicant/Sponsor: Alkermes OSE RCM #: 2014-1849 ***This document contains proprietary and confidential information that should not be released to the public*** Reference ID: 3828483 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Product Background............................................................................................ 1 1.2 Disease Background............................................................................................ 2 1.3 Regulatory History ............................................................................................. -

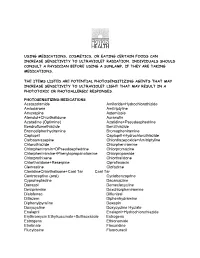

Using Medications, Cosmetics, Or Eating Certain Foods Can Increase Sensitivity to Ultraviolet Radiation

USING MEDICATIONS, COSMETICS, OR EATING CERTAIN FOODS CAN INCREASE SENSITIVITY TO ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION. INDIVIDUALS SHOULD CONSULT A PHYSICIAN BEFORE USING A SUNLAMP, IF THEY ARE TAKING MEDICATIONS. THE ITEMS LISTED ARE POTENTIAL PHOTOSENSITIZING AGENTS THAT MAY INCREASE SENSITIVITY TO ULTRAVIOLET LIGHT THAT MAY RESULT IN A PHOTOTOXIC OR PHOTOALLERGIC RESPONSES. PHOTOSENSITIZING MEDICATIONS Acetazolamide Amiloride+Hydrochlorothizide Amiodarone Amitriptyline Amoxapine Astemizole Atenolol+Chlorthalidone Auranofin Azatadine (Optimine) Azatidine+Pseudoephedrine Bendroflumethiazide Benzthiazide Bromodiphenhydramine Bromopheniramine Captopril Captopril+Hydrochlorothiazide Carbaamazepine Chlordiazepoxide+Amitriptyline Chlorothiazide Chlorpheniramine Chlorpheniramin+DPseudoephedrine Chlorpromazine Chlorpheniramine+Phenylopropanolamine Chlorpropamide Chlorprothixene Chlorthalidone Chlorthalidone+Reserpine Ciprofloxacin Clemastine Clofazime ClonidineChlorthalisone+Coal Tar Coal Tar Contraceptive (oral) Cyclobenzaprine Cyproheptadine Dacarcazine Danazol Demeclocycline Desipramine Dexchlorpheniramine Diclofenac Diflunisal Ditiazem Diphenhydramine Diphenylpyraline Doxepin Doxycycline Doxycycline Hyclate Enalapril Enalapril+Hydrochlorothiazide Erythromycin Ethylsuccinate+Sulfisoxazole Estrogens Estrogens Ethionamide Etretinate Floxuridine Flucytosine Fluorouracil Fluphenazine Flubiprofen Flutamide Gentamicin Glipizide Glyburide Gold Salts (compounds) Gold Sodium Thiomalate Griseofulvin Griseofulvin Ultramicrosize Griseofulvin+Hydrochlorothiazide Haloperidol -

207533Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 207533Orig1s000 MEDICAL REVIEW(S) CLINICAL REVIEW Application Type NDA Application Number(s) 207553 Priority or Standard Standard Submit Date(s) 8/22/2014 Received Date(s) 8/22/2014 PDUFA Goal Date 8/22/2015 Division / Office DPP/ODE1 Reviewer Name(s) Lucas Kempf, MD Review Completion Date October 2, 2015 Established Name Aripiprazole lauroxil (Proposed) Trade Name Aristada Therapeutic Class Antipsychotic Applicant Alkermes Inc. Formulation(s) Extended release injection Dosing Regimen Suspension/ IM up to 6 weeks Indication(s) Schizophrenia Intended Population(s) Schizophrenia Template Version: March 6, 2009 Reference ID: 3806701 Clinical Review Lucas Kempf, MD NDA 207533 Aristada, Aripiprazole lauroxil Table of Contents 1 RECOMMENDATIONS/RISK BENEFIT ASSESSMENT ......................................... 7 1.1 Recommendation on Regulatory Action ............................................................. 7 1.2 Risk Benefit Assessment .................................................................................... 7 1.3 Recommendations for Postmarket Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies ... 8 1.4 Recommendations for Postmarket Requirements and Commitments ................ 8 2 INTRODUCTION AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND ........................................ 8 2.1 Product Information ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Currently Available Treatments for Proposed Indications .................................. -

Antipsychotics for Migraines, Cluster Headaches, and Nausea

Web extra Antipsychotics for migraines, cluster headaches, and nausea Evidence of efficacy for these conditions is limited, and risk of side effects may inhibit use ost evidence supporting antipsychotics as a treat- ment for migraine headaches and cluster head- Maches is based on small studies and chart reviews. Some research suggests antipsychotics may effectively treat nausea but side effects such as akathisia may limit their use. Migraine headaches Antipsychotic treatment of migraines is supported by the theory that dopaminergic hyperactivity leads to migraine headaches (Table 1, page E2). Antipsychotics have been used off-label in migraine patients who do not tolerate triptans or have status migrainosus—intense, debilitating migraine JON KRAUSE FOR CURRENT PSYCHIATRY lasting >72 hours.1 Primarily a result of D2 receptor block- ade, the serotonergic effects of some second-generation anti- Aveekshit Tripathi, MD psychotics (SGAs) may prevent migraine recurrence. The Senior Resident Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) prochlorperazine, droperidol, haloperidol, and chlorpromazine have been Matthew Macaluso, DO Assistant Professor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences 1-27 used for migraine headaches (Table 2, page E3). Associate Director, Residency Training Prochlorperazine may be an effective treatment of acute • • • • headaches9 and refractory chronic daily headache.10 Studies show that buccal prochlorperazine is more effective than oral University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita Wichita, KS ergotamine tartrate11 and IV prochlorperazine is more effective than IV ketorolac12 or valproate28 for treating acute headache. Evidence suggests that chlorpromazine administered IM2 or IV3 is better than placebo for managing migraine pain. In a study comparing IV chlorpromazine, lidocaine, and dihydroergotamine, patients treated with chlorproma- zine showed more persistent headache relief 12 to 24 hours post-dose.4 In another study, IV chlorpromazine, 25 mg, Current Psychiatry was as effective as IM ketorolac, 60 mg.5 Vol. -

Drug-Induced Parkinsonism

InformationInformation Sheet Sheet Drug-induced Parkinsonism Terms highlighted in bold italic are defined in increases with age, hypertension, diabetes, the glossary at the end of this information sheet. atrial fibrillation, smoking and high cholesterol), because of an increased risk of stroke and What is drug-induced parkinsonism? other cerebrovascular problems. It is unclear About 7% of people with parkinsonism whether there is an increased risk of stroke with have developed their symptoms following quetiapine and clozapine. See the Parkinson’s treatment with particular medications. This UK information sheet Hallucinations and form of parkinsonism is called ‘drug-induced Parkinson’s. parkinsonism’. While these drugs are used primarily as People with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease antipsychotic agents, it is important to note and other causes of parkinsonism may also that they can be used for other non-psychiatric develop worsening symptoms if treated with uses, such as control of nausea and vomiting. such medication inadvertently. For people with Parkinson’s, other anti-sickness drugs such as domperidone (Motilium) or What drugs cause drug-induced ondansetron (Zofran) would be preferable. parkinsonism? Any drug that blocks the action of dopamine As well as neuroleptics, some other drugs (referred to as a dopamine antagonist) is likely can cause drug-induced parkinsonism. to cause parkinsonism. Drugs used to treat These include some older drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders high blood pressure such as methyldopa such as behaviour disturbances in people (Aldomet); medications for dizziness and with dementia (known as neuroleptic drugs) nausea such as prochlorperazine (Stemetil); are possibly the major cause of drug-induced and metoclopromide (Maxolon), which is parkinsonism worldwide. -

Association Between Antipsychotic Agents and Risk of Acute Respiratory Failure in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Research JAMA Psychiatry | Original Investigation Association Between Antipsychotic Agents and Risk of Acute Respiratory Failure in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Meng-Ting Wang, PhD; Chen-Liang Tsai, MD; Chen Wei Lin, BS; Chin-Bin Yeh, MD, PhD; Yun-Han Wang, MS, BPharm; Hui-Lan Lin, ADN, RRT Supplemental content IMPORTANCE Acute respiratory failure (ARF) is a life-threatening event that has been linked in case reports to antipsychotic use, but this association lacks population-based evidence. Particular attention should be focused on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) regarding this drug safety concern because these patients are prone to ARF and are commonly treated with antipsychotics. OBJECTIVE To determine whether the use of antipsychotics is associated with an increased risk of ARF in patients with COPD. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A population-based case-crossover study analyzing the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database was conducted of all patients with COPD, who were newly diagnosed with ARF in hospital or emergency care settings necessitating intubation or mechanical ventilation from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2011. Patients with prior ARF, lung cancer, and cardiogenic, traumatic, or septic ARF were excluded to analyze idiopathic ARF. The pilot study was conducted from November 1 to December 31, 2013, and full data analysis was performed from October 15, 2015, to November 8, 2016. EXPOSURES The use of antipsychotics was self-compared during days 1 to 14 (the risk period according to previous case reports) and days 75 to 88 (control period) preceding the ARF event or index date. The antipsychotic class, route of administration, and dose were also examined. -

Induced Nausea and Vomiting (CINV): a Retrospective Study

Original Article Olanzapine for the prophylaxis and rescue of chemotherapy- induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): a retrospective study Leonard Chiu, Nicholas Chiu, Ronald Chow, Liying Zhang, Mark Pasetka, Jordan Stinson, Breanne Lechner, Natalie Pulenzas, Sunil Verma, Edward Chow, Carlo DeAngelis Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada Contributions: (I) Conception and design: L Chiu, E Chow, C DeAngelis; (II) Administrative support: L Chiu, N Chiu; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: C DeAngelis, E Chow; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: L Chiu, L Zhang; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: L Chiu, L Zhang; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Dr. Edward Chow, MBBS, MSc, PhD, FRCPC. Department of Radiation Oncology, Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, 2075 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M5, Canada. Email: [email protected]. Background: While the efficacy of olanzapine in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) has been documented, the literature on the use of olanzapine as a rescue medication for breakthrough CINV has been scarce. The following study retrospectively evaluated the safety and efficacy of olanzapine for the treatment of breakthrough CINV. The efficacy and safety of olanzapine in the prophylactic setting was also examined in a smaller cohort. Methods: Electronic medical records of adult patients aged >17 years receiving a prescription for olanzapine from the Odette Cancer Centre Pharmacy at Sunnybrook Hospital between January 2013 and June 2015 were reviewed retrospectively. Inclusion criteria required receiving one or more doses of olanzapine for the rescue or prophylaxis of CINV and documentation of the outcome.