The Yale University Brasher Doubloon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July/August 2014 Vol

July/August 2014 Vol. 56 - No. 4 July/August 2014 Volume 56, Number 4 Greetings................................................................1. Ron Kersey From.the.President.....................................................2 Debbie Williams This year is going fast, or does it just seem that way as a person gets older? I remember when I couldn’t wait TNA.Ad.Rates.&.Copy.Information...............................4 for the birthday that would allow me to get a driver’s Secretary’s.Report.....................................................5 license - time moved so... slow! Or the holidays that Larry Herrera seemed they would never arrive. Financial.Assistance.Programs.&.Treasurer’s.Report........ 6-7 Jack Gilbert Special events are looked forward to by young people. Our Youth Chair, Dr. Ralph Ross, has been doing a great ANA.News.............................................................8 job of taking numismatics to his High School and the Cleaned.at.the.Last.Minute.........................................9 community. Be sure to read his account on page 14. The John Barber looks on those kids’ faces says it all. Nuremberg’s.Numismatic.Salute............................. 10-13 Mike Ross There was a very pleased look on my face when I received an email from Jerri Raitz, Senior Editor of Jack.Yates.Senior.High.School.-.Lion.Coin.Club............. 14 Dr. Ralph Ross ANA’s “The Numismatist” magazine. “TNA News” has been selected to receive the second-place ANA Red-Brown.Cents.................................................... 15 Outstanding Regional Club Publication Award. Our Sam Fairchild award will be presented at the ANA’s World’s Fair of Questions.for.Dr..Coyne....................................... 16-17 Money Convention in Chicago on August 9th. Dr. Ralph Numismatic.History.from.the.“Coin.Cabinet”….......... 18-19 Ross, our TNA Exhibit and Youth Chair, as well as our Richard Laster ANA Governor, has agreed to accept this award on My.2014.ANA.Summer.Seminar.Adventure.............20-21 behalf of the Texas Numismatic Association. -

YOUR LAND and .,1" �,Nil.„,,9 : �1; �V.11" I, ,, 'Ow ,, �.� 01,� �; by F•W•R-I-Ti`I'''� --:-— , --I-„‘," ."; ,,, R \, • •

, .„,, „,,,.-1 Ie. • r•11.,; s v_ .:11;.--''' . %. ....:. _,11,101, ol'I - -, 1,' o‘ v. - w •-• /...1a. ,'' ,,,- cy,of 10.0 \1,,IV _, , .01 ,;„,---- ', A 0, 016 „YOUR LAND AND .,1" ,Nil.„,,9 : 1; V.11" I, ,, 'ow ,, . 01, ; BY f•w•r-i-ti`I''' --:-— , --i-„‘," ."; ,,, r \, • • . O" ;._ . • N - .„t• .10 EDMUND W. VIGUERS 1 k , Iv' . • o': jrar.'!:, ..\ . , ...---1,4 s.., •-, 11"‘‘ 0 re 't' -----.V . ov1 .00 - II''',05‘ 410,1N ' --$A 01' 0' :•-..-•-• 1,,, lc -. ..00', 1 1 01 ,t,s1' . .01. ' . 113, ....-- 7-7. no". VI' • k‘"' .% ,00- IP' \i'l,ili, ,..., 1,'"° A1 "45 -,..., • N'' Ilt' ' 1 S' is 00,?' ill i 1, ,. R P• s.----,.. ,• , .10!..i01 , coil it 04,1 ' A ' .i ,N ‘ $v" ,. .‘i`‘ \\‘‘ 7,,.....111S \\ ‘i •• 71--. •--N.--.... •S'" fr. 101' • V . NNO . ft -• Iii‘...r1:;::::::11 ..., \''' • ' . 571:1:1)- . ''._;'' . •• A :::::::e 00c's:` ,,i i sCs•l‘ •`• ; ,,,Ai‘ •/ / ‘%5' S , Is i\ S' Y' , 6,•,,,y,,,.ib,,,, - /7 ()ME 111,7%W1: \\ 0" (..' \• 1' e...":;...... MM. : t " , ,,, , , , !....... \ ‘ s- ,..1. %.,.- '40) ‘‘‘s i - .1\''' '.:.. 01, 4.-. 1 • •••• C L" V (vi "':- ‘,5..‹.' • ' .‘AV *: ,v , 6s"-1.);',:.;'.,•-•>•' .:F:''..b;,„. I ,10 .i ,‘,, 4\ xt• .!, .0,. •,,,,,,,/7,,, , rrz •• ivo 1.,:i. te 7.1+10,-Pumbn DEN, ' NI,I. '\‘` \ ci • , \ lk9 o'' „,..,...,.. • ,,,,,A ,No , i ,r• ----. 110 0 . • •• 00 c„,-i.. r vS• , , ,,v s r. .,..va lCt° ::1//dr4,11;44nron ; . ,;kf c1 +IV eirsimint ‘\ \ ‘ •AO " e „, Ont 50. .0. .... .--, --: ,t‘" V, e VP R) l'N \G II k-:., L ss,.. 0 ' ---::- _ V01.--.,01'\,‘" vO „„ ,-. 7, • . -

Rarities Night

RARITIES NIGHT The March 2021 Auction March 25, 2021 Stack’s Bowers Galleries Upcoming Auction Schedule Coins and Currency Date Auction Consignment Deadline March 10, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – U.S. Coins & Currency Visit StacksBowers.com StacksBowers.com March 23-26, 2021 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency Visit StacksBowers.com March 2021 Showcase Auction Las Vegas, Nevada April 5-8, 2021 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – Chinese & Asian Coins & Banknotes Visit StacksBowers.com Official Auction of the Hong Kong Coin Show Hong Kong April 14, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – U.S. Coins & Currency March 22, 2021 StacksBowers.com May 12, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – World Paper Money March 29, 2021 StacksBowers.com May 19, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – U.S. Coins & Currency April 26, 2021 StacksBowers.com June 2-4, 2021 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency April 8, 2021 June 2021 Showcase Auction June 22-24, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – Ancient & World Coins May 11, 2021 StacksBowers.com August 10-14, 2021 Stack’s Bowers Galleries June 10, 2021 Ancient and World Coins & Paper Money; U.S. Coins & Currency An Official Auction of the ANA World’s Fair of Money Rosemont, IL September 6-8, 2021 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – Chinese & Asian Coins & Banknotes June 24, 2021 Official Auction of the Hong Kong Coin Show Hong Kong October 12-14, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – Ancient & World Coins August 31, 2021 StacksBowers.com October 27, 2021 Collectors Choice Online Auction – World Paper Money September 13, 2021 StacksBowers.com Front Cover: Lot 4081: 1797 Draped Bust Half Dollar. -

Heritage Auctions | Winter 2020-2021 $7.9 9

HERITAGE AUCTIONS | WINTER 2020-2021 $7.9 9 BOB SIMPSON Texas Rangers Co-Owner Releases Sweet Nostalgia Enduring Charm Auction Previews Numismatic Treasures Yes, Collectibles Bright, Bold & Playful Hank Williams, Provide Comfort Luxury Accessories Walt Disney, Batman features 40 Cover Story: Bob Simpson’s Sweet Spot Co-owner of the Texas Rangers finds now is the time to release one of the world’s greatest coin collections By Robert Wilonsky 46 Enduring Charm Over the past 12 months, collectors have been eager to acquire bright, bold, playful accessories By The Intelligent Collector staff 52 Tending Your Delicates Their fragile nature means collectible rugs, clothing, scarfs need dedicated care By Debbie Carlson 58 Sweet, Sweet Nostalgia Collectibles give us some degree of comfort in an otherwise topsy-turvy world By Stacey Colino • Illustration by Andy Hirsch Patek Philippe Nautilus Ref. 5711/1A, Stainless Steel, circa 2016, from “Enduring Charm,” page 46 From left: Hank Williams, page 16; Harrison Ellenshaw, page 21; The Donald G. Partrick collection, page 62 Auction Previews Columns 10 21 30 62 How to Bid Animation Art: The Arms & Armor: The Bill Coins: Rare Offering The Partrick 1787 New York-style 11 Ellenshaw Collection Bentham Collection Disney artist and son worked California veterinarian’s Civil Brasher doubloon is one of only seven- Currency: The Del Monte Note on some of Hollywood’s War artifacts include numerous known examples Banana sticker makes bill one greatest films fresh-to-market treasures By David Stone of the most famous -

RE NOT REALLY COINS Audio-Visual Service Chas

TlST OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ONTARIO NUMISMATIC ASSOCIATION I VOLUME 22 NOVEMBER 1983 PAGE 146 O.N.A. OFFICERS Pmt Pnrid.nts R.R.Rekotrkl(1~43) L.T. Smith (lQ65-$7) W. English (1W37-69) D. Flick(ltM$ .71) C.B. brlsler (1971-73) W .E.P. Lambrt (1973-75) E. Jeohson (1975-77) J3.R- Watt (1977-1981) F.C. Jewett (1981-1983 President Stella Hodge Firs! Vice-President R . Hollingshead Second Vice-President Ken Wilrnot . Secretary THOMAS MASTERS Treasurer and Membership BRUCE H. RASZMANN Mailing Address Box 33, Waterloo, Ont. N2J 326 I DIRECTORS AREA la H. Whitfield .%b T. Kosztaluk 2 C.B. Laister 3 Vacant 4 B- ~letchek 5a Wm. Gordon 5b Tom Kennedy 6 W. Ham 7 Walter Ciona 8 Ed. Keetch 9 Len Fletcher. 10 R. Albert 'THEY ARE THE MOST VALUABLE AMERICAN COINS, Head Judge Elmer Workman BUT THEY'RE NOT REALLY COINS Audio-Visual Service Chas. B. Laister No. 3 Highway Tillsonburg, Ont. N4G 3J1 Editor THE ONTARIO NUMISMATIST Is published by the Ontario Bruce R. Watt Numismatic Association. The publlcation can be obtained with ,153 Northridge St., membership in one of the foliowlng categories: Regular Membership 9.00 annually. Husband and Wife (one journal) $9.00 Oshawa, 'Ontario,LlG 3P3 annually. Junior (up to 18) $3.00 annually. Club Membership $10.00 Librarian annually. Life Memberships available for $50.00 after 3 years of Thomas Masters regular rnem bershlp. 823 Van Strtht, Remittances payable to the Ontarlo NumIsmrtlc Assoclatlon, P.O. London, Ontario N5Z 1M8 Box 33, Waterloo. Ontarlo. N2J 326. -

Strangers in Purgatory: on the “Jewish Experience,” Film Noir, and Émigré Actors Fritz Kortner and Ernst Deutsch Marc Svetov April 23, 2017

Enter your search... ABOUT ARTISTS MOVIES GENRES TV & STREAMING BOOKS CONTRIBUTORS SUBSCRIBE ADS 3 ACTORS & PERSONALITIES · NOIR · WAR Strangers in Purgatory: On the “Jewish Experience,” Film Noir, and Émigré Actors Fritz Kortner and Ernst Deutsch Marc Svetov April 23, 2017 BLFJ Flip by BLFJ Read Magazine LINKS Ernst Deutsch in The Third Man (screenshot) Weird Band Names An examination of two of these émigrés – Fritz Kortner and Ernst Deutsch, major Central European actors, very well known in their home countries before leaving them in duress, both of whom relocated to Hollywood – offers exemplary lessons of what it meant for artists to be forced to leave Europe. * * * Two German Jews are sitting in a Berlin park Vouchers for Top UK Stores in the early years of the Nazi rule. One of them is reading the Völkische Beobachter, the Nazi rag. The other German Jew is reading the Jewish Aufbau and is slowly getting excited. Finally, he asks his countryman, “Why are you reading that Jew-baiting rag?” The first German Jew stares at the floor a few seconds, then replies: “Look here. What’s printed in your newspaper? Everywhere Jews are refugees. They persecute us. They kill us. They are burning down our synagogues, seize our property and ban us from our professions. When I’m reading the Nazi paper, I read: ‘Jews own the banks!’, ‘Jews own all the big corporations!’, ‘Jews are so smart and clever they control the world!’ I tell you it makes me feel great!” I was reminded of this classic Jewish joke while reading Vincent Brook’s Driven to Darkness (2009), about the influence of the “Jewish experience” on film noir. -

Vol. 22, No. 2, November

Ewing Family Journal Volume 22 – Number 2 November 2016 ISSN: 1948-1187 Published by: Ewing Family Association www.EwingFamilyAssociation.org Ewing Family Association 1330 Vaughn Court Aurora, Illinois 60504 www.EwingFamilyAssociation.org CHANCELLOR Beth (Ewing) Toscos [email protected] PAST CHANCELLORS 2012-2016 Wallace K ‘Wally’ Ewing [email protected] 2006-2012 David Neal Ewing [email protected] 2004-2006 George William Ewing [email protected] 1998-2004 Joseph Neff Ewing Jr. 1995-1998 Margaret (Ewing) Fife 1993-1995 Rev. Ellsworth Samuel Ewing BOARD OFFICERS and DIRECTORS Vice-Chancellor Treasurer Secretary Terry (Ewing) Schulz Linda 'Lynn' (Ewing) Coughlin Jane P. (Ewing) Weippert [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Karen Avery Daniel C. Ewing David Neal Ewing [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lawrence ‘Larry’ E. Ewing Martin S. Ewing [email protected] [email protected] Wallace K. Ewing Walter E. ‘Major’ Ewing Immediate Past Chancellor, ex officio [email protected] [email protected] ACTIVITY COORDINATORS Archivist Genealogist Gathering Daniel C. Ewing Karen Avery Wallace K. Ewing [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Internet Services Journal Membership Martin S. Ewing John A. Ewing, Editor Terry (Ewing) Schulz [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] New Members Clan Ewing Standing Committee Y-DNA Project Jane P. (Ewing) Weippert Walter E. ‘Major’ Ewing, Chairman David Neal Ewing [email protected] Lawrence ‘Larry’ E. Ewing [email protected] David Neal Ewing Commander Thor Ewing, ex officio [email protected] ISSN: 1948-1187 Ewing Family Journal Volume 22 Number 2 November 2016 Published by: Ewing Family Association, 1330 Vaughn Court, Aurora, IL 60504 Web Site: www.EwingFamilyAssociation.org The Ewing Family Journal is published semi-annually. -

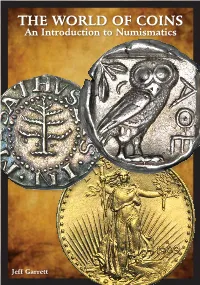

THE WORLD of COINS an Introduction to Numismatics

THE WORLD OF COINS An Introduction to Numismatics Jeff Garrett Table of Contents The World of Coins .................................................... Page 1 The Many Ways to Collect Coins .............................. Page 4 Series Collecting ........................................................ Page 6 Type Collecting .......................................................... Page 8 U.S. Proof Sets and Mint Sets .................................... Page 10 Commemorative Coins .............................................. Page 16 Colonial Coins ........................................................... Page 20 Pioneer Gold Coins .................................................... Page 22 Pattern Coins .............................................................. Page 24 Modern Coins (Including Proofs) .............................. Page 26 Silver Eagles .............................................................. Page 28 Ancient Coins ............................................................. Page 30 World Coins ............................................................... Page 32 Currency ..................................................................... Page 34 Pedigree and Provenance ........................................... Page 40 The Rewards and Risks of Collecting Coins ............. Page 44 The Importance of Authenticity and Grade ............... Page 46 National Numismatic Collection ................................ Page 50 Conclusion ................................................................. Page -

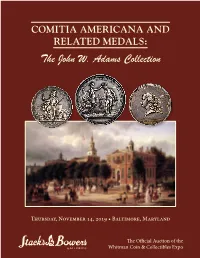

The John W. Adams Collection Comitia Americana and Related Medals: the John W

COMITIA AMERICANA AND RELATED MEDALS: The John W. Adams Collection Comitia Americana and Related Medals: The John W. Adams Collection Adams W. John The Medals: Related and Americana Comitia November 14, 2019 November Thursday, November 14, 2019 • Baltimore, Maryland The Official Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Expo Stack’s Bowers Galleries Upcoming Auction Schedule Coins and Currency Date Auction Consignment Deadline November 12-16, 2019 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency Visit StacksBowers.com Official Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD December 11, 2019 Collectors Choice Online Auction – U.S. Coins & Currency November 22, 2019 StacksBowers.com January 17-18, 2020 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – Ancient and World Coins & Paper Money November 12, 2019 An Official Auction of the N.Y.I.N.C. New York, NY March 18-20, 2020 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency January 20, 2020 Official Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD March 23-25, 2020 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – Chinese & Asian Coins & Banknotes January 14, 2020 Official Auction of the Hong Kong Coin Show Hong Kong June 18-19, 2020 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Currency April 21, 2020 Official Auction of the Whitman Coin & Collectibles Baltimore Expo Baltimore, MD August 4-7, 2020 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – Ancient and World Coins & Paper Money May 29, 2020 An Official Auction of the ANA World’s Fair of Money Pittsburgh, PA August 4-7, 2020 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. Coins & Paper Money June 9, 2020 An Official Auction of the ANA World’s Fair of Money Pittsburgh, PA August 17-19, 2020 Stack’s Bowers and Ponterio – Chinese & Asian Coins & Banknotes June 9, 2020 Official Auction of the Hong Kong Coin Show Hong Kong November 2020 Stack’s Bowers Galleries – U.S. -

The Problem Body Projecting Disability on Film

The Problem Body The Problem Body Projecting Disability on Film - E d i te d B y - Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotic’ T h e O h i O S T a T e U n i v e r S i T y P r e ss / C O l U m b us Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The problem body : projecting disability on film / edited by Sally Chivers and Nicole Markotic´. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1124-3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9222-8 (cd-rom) 1. People with disabilities in motion pictures. 2. Human body in motion pictures. 3. Sociology of disability. I. Chivers, Sally, 1972– II. Markotic´, Nicole. PN1995.9.H34P76 2010 791.43’6561—dc22 2009052781 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1124-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9222-8) Cover art: Anna Stave and Steven C. Stewart in It is fine! EVERYTHING IS FINE!, a film written by Steven C. Stewart and directed by Crispin Hellion Glover and David Brothers, Copyright Volcanic Eruptions/CrispinGlover.com, 2007. Photo by David Brothers. An earlier version of Johnson Cheu’s essay, “Seeing Blindness On-Screen: The Blind, Female Gaze,” was previously published as “Seeing Blindness on Screen” in The Journal of Popular Culture 42.3 (Wiley-Blackwell). Used by permission of the publisher. Michael Davidson’s essay, “Phantom Limbs: Film Noir and the Disabled Body,” was previously published under the same title in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Volume 9, no. -

2018 Transline Product Price List Visit for Complete Product Detail

List Creation Date Sunday, May 20, 2018 2018 Transline Product Price List Visit www.translinesupply.com for complete product detail ITEM # Vend # Trade Name UPC / Product MSRP Wholesale Qty 2 Price 2 Qty 3 Price 3 Shipping & Transportation>Tapes & Dispensers 1514 497825 3M - Tartan Box Sealing Tape $4.55 $3.0536 $2.800 72 $2.550 1518 375 3M - Scotch Box Sealing Tape 3M Clear $11.12 $7.2036 $6.600 72 $6.110 1524 371018 3M - Tartan Filament Tape 3/4"x60 yards 8934 Clear $5.00 $3.7548 $3.130 96 $2.800 1526 371579 3M - Tartan Filament Tape 1"x60yards $6.15 $4.6036 $3.990 72 $3.500 1528 474096 3M - Tartan Filament Tape 2"x60 yards $11.65 $9.9024 $9.300 48 $7.800 1540 893 3M 371563 - Scotch Filament Tape 1" x 60 yards $16.75 $12.5036 $12.000 72 $11.730 1542 893-1540 3M - Scotch Filament Tape 2" x 60 yards $37.50 $25.1024 $23.900 48 $22.700 1564 673006: 250 Grad Central - Reinforced Tape $15.50 $10.5010 $9.550 20 $8.750 1582 H-190 3M - Scotch Tape Dispenser $24.00 $14.40 1586 376290 3M - 1" Strapping Tape Dispenser 3M-H-10 $23.50 $14.10 Shipping & Transportation>Envelope Mailers & Box Mailers 2135 240140107 MMF 078541220171 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Cent Bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 2136 240140508 MMF 078541220584 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Nickel bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 2137 240141002 MMF 078541221024 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Dime Bulk $76.30 $51.503 $47.690 2138 240142516 MMF 078541222557 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Quarter Bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 2139 240141101 MMF - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Dollar Bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 1400 FOS-8FX16F -

September Spotlight Coin Auction Featuring Gold, Silver, Commemoratives, US Change and Foreign Coins Sellers: Ruth and the Late Dr

September Spotlight Coin Auction Featuring Gold, Silver, Commemoratives, US Change and Foreign Coins Sellers: Ruth and the Late Dr. Lucky Simpson Sunday, September 11, 2016 at 11:00 AM Norton Community Building 208 West Main Norton, Kansas Conducted by McEwen Auction of Norton, Kansas Duane R. McEwen - Auctioneer Phone Contact -- 785-877-3032 Lunch Stand Available There are no reserves on the coins from the Simpson family Auctioneer Note: This coin auction features rare and unusual coins with no reserves. Dr. Simpson spent his life as a Veterinarian in Canada and returned to the states after he retired. Ruth was a local gal. She and Lucky decided to return to her roots here in Norton County in their later years. I became acquainted with Lucky as he visited Norton and came to auctions. His appreciation for coins was easy to see. Once he and Ruth settled in Norton, his love for fine collections was very appreciated. It is with great honor that McEwen Auction has been selected to conduct this “September Spotlight Sale” for the Simpsons. You will appreciate the fine coins in this auction and probably never see this amount of gold, silver and commemoratives in one collection. Indian Head Cents: Lot 1 1885,1891 Indian Head (2 Coins) Lot 2 1900, 1901,1902,1903, Indian Head Cents (4 Coins) Lot 3 1900, 1902, 1903, 1903 Indian Head Cents (4 Coins) Lot 4 (3) 1905, 1907,1907 Indian Head Cents (5 Coins) Lot 5 The Last Twenty Years of Indian Cents (Book) Wheat Pennies: Lot 1 Assorted Wheat Pennies (59 Coins) Lot 2 (6) 1964 Proofs Memorial Pennies Lot