Television Talk Show Viewing and Political Engagement I Laughing All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69 An Analysis of the Political Affiliations and Professions of Sunday Talk Show Guests Between the Obama and Trump Administrations Jack Norcross Journalism Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract The Sunday morning talk shows have long been a platform for high-quality journalism and analysis of the week’s top political headlines. This research will compare guests between the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency and the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. A quantitative content analysis of television transcripts was used to identify changes in both the political affiliations and profession of the guests who appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” CBS’s “Face the Nation,” ABC’s “This Week” and “Fox News Sunday” between the two administrations. Findings indicated that the dominant political viewpoint of guests differed by show during the Obama administration, while all shows hosted more Republicans than Democrats during the Trump administration. Furthermore, U.S. Senators and TV/Radio journalists were cumulatively the most frequent guests on the programs. I. Introduction Sunday morning political talk shows have been around since 1947, when NBC’s “Meet the Press” brought on politicians and newsmakers to be questioned by members of the press. The show’s format would evolve over the next 70 years, and give rise to fellow Sunday morning competitors including ABC’s “This Week,” CBS’s “Face the Nation” and “Fox News Sunday.” Since the mid-twentieth century, the overall media landscape significantly changed with the rise of cable news, social media and the consumption of online content. -

Corneliailie

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289370357 Talk Shows Article · December 2006 DOI: 10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00357-6 CITATIONS READS 24 4,774 1 author: Cornelia Ilie Malmö University 57 PUBLICATIONS 476 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Parenthetically Speaking: Parliamentary Parentheticals as Rhetorical Strategies View project All content following this page was uploaded by Cornelia Ilie on 09 December 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction or distribution or commercial use This article was originally published in the Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second Edition, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non- commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Ilie C (2006), Talk Shows. In: Keith Brown, (Editor-in-Chief) Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second Edition, volume 12, pp. 489-494. Oxford: Elsevier. Talk Shows 489 Talk Shows C Ilie,O¨ rebro University, O¨ rebro, Sweden all-news radio programs, which were intended as ß 2006 Elsevier Ltd. -

Merri Dee's Legendary Award-Winning 49-Year Career in Chicago Broadcasting Is Admirable in Itself

E-mail: www.merridee.com Merri Dee Communications Merri Dee's legendary award-winning 49-year career in Chicago broadcasting is admirable in itself. She was the Illinois Lottery’s First Lady, anchored the first edition of midday news and sports, hosted a magazine- style TV show and served in management as Director of Community Relations. One of the first African- American women to anchor the news in the Windy City, Dee has parlayed her celebrity into charitable success, powerful motivational speaking and advocacy. She has raised millions of dollars for children's charities, spearheaded victims' rights legislation, and helped increase adoption rates across the nation. In 1966, Merri Dee landed her first radio position with WBEE in Harvey, Illinois. She was one of the first female DJs on WSDM radio and opened her four-hour radio show at WBEE as “Merri Dee the Honeybee.” During the next year, Dee developed a following in Chicago radio, becoming a local celebrity. In 1967 she made the leap to television quickly with WCIU Chicago as host of a Saturday primetime entertainment show. By 1970 Dee hosted her own talk show, The Merri Dee Show, on WSNS Channel 44. In 1972 Dee was hired as an anchor for Chicago’s WGN-TV. After 11 years in various on-air positions, Dee moved into administration and became the station’s Director of Community Relations and Manager of its Children’s Charities. One of the few African-American women in broadcasting at the time, Dee was becoming one of the most successful. She became a trusted advisor. -

Language of American Talk Show Hosts

LANGUAGE OF AMERICAN TALK SHOW HOSTS - Gender Based Research on Oprah and Dr. Phil Författare: Erica Elvheim Handledare: Michal Anne Moskow, PhD Enskilt arbete i Lingvistik 10 poäng, fördjupningsnivå 1 10 p Uppsats Institutionen för Individ och Samhälle February 2006 © February 2006 Table of Contents: 1. Introduction and Importance of the Problem………………….…………….3 2. Statement of the Problem…………………………………………………...…4 3. Literature Review…………………………………………………………..4 - 8 4. Methods…………………………………………………………………….…...9 5. Delimitations and Limitations………………………………………..…...9 - 10 6. Definitions………………………………………...………………………10 - 12 7. Findings……………………………………………………...…………...12 – 25 7.1. Speech-event………………………………………………………….13 - 15 7.2. Swearwords, slang and expressions…………………………….…….15 - 16 7.3. Interruptions, minimal- and maximal responses………………...……16 - 18 7.4. Tag-questions…………………………………………………………18 - 20 7.5. “Empty” adjectives……………………………………………...……20 - 21 7.6. Hedges…………………………………………………………...……21 - 22 7.7. Repetitions...................………………………………………….……22 - 23 7.8. Power and Command…....…………………………………….…...…23 - 25 8. Conclusion……………………………………………………………..…25 - 29 9. Works Cited…………………………………………………………………...30 10. Appendix………………………………………………………………….31 - 68 2 1. Introduction: The Talk Show concept is a modern mass media phenomenon. The Oprah and Dr Phil show are aired in countries all over the world. People seem to have a huge interest in other people’s lives and there seem to be an amazingly endless line of topics to talk about. Celebrities, placed in a fake comfort zone that they can’t escape, are forced to talk about their personal business. People just like you and me are willing to tell all about their problems on a TV- show that is aired to millions of people. I can’t let go of my contradictory feelings concerning talk shows – I am fascinated but at the same time scared about how a person can make a total stranger feel so comfortable in front of millions of people. -

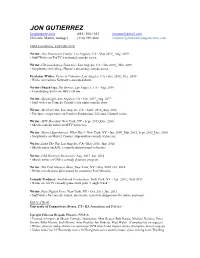

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.Com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, Manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected]

JON GUTIERREZ Jongutierrez.com (845) 300-1683 [email protected] Christine Martin, manager (310) 919-4661 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Writer, This Functional Family, Los Angeles, CA • May 2019_ Aug. 2019 • Staff Writer on TruTV’s animated comedy series. Writer, Ultramechatron Team Go!, Los Angeles, CA • Jan. 2019_ Mar. 2019 • Scriptwriter on College Humor’s streaming comedy series. Freelance Writer, Victor & Valentino, Los Angeles, CA • Oct. 2018_ Dec. 2018 • Writer on Cartoon Network’s animated show. Writer (Punch Up), The Detour, Los Angeles, CA • Aug. 2018 • Contributing writer on TBS’s sitcom. Writer, @midnight, Los Angeles, CA • Feb. 2017_Aug. 2017 • Staff writer on Comedy Central’s late night comedy show. Writer, My Crazy Sex, Los Angeles, CA • April. 2016_Aug. 2016 • Freelance script writer on Painless Productions’ Lifetime Channel series. Writer, MTV Decoded, New York, NY • Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Sketch comedy writer on MTV webseries. Writer, Marvel Superheroes: What The!?, New York, NY • Jan. 2009_May 2012, Sept. 2015_Dec. 2016 • Scriptwriter on Marvel Comics’ stop-motion comedy webseries. Writer, Land The Gig, Los Angeles, CA • May 2016_June 2016 • Sketch writer on AOL’s comedy/instructional webseries. Writer, CBS Diversity Showcase • Aug. 2015_Jan. 2016 • Sketch writer on CBS’s comedy diversity program. Writer, The Paul Mecurio Show, New York, NY • May 2014_Oct. 2014 • Writer on talk show pilot hosted by comedian Paul Mecurio. Comedy Producer, NorthSouth Productions, New York, NY • Apr. 2013_ May 2013 • Writer on TruTV comedy game show pilot “Laugh Truck.” Writer, Fuse Digital News, New York, NY • Oct. 2011_Jan. 2013 • Staff writer for comedy videos, interviews, news hits and promos for online and onair. -

The Talk Show: Using TV to Talk with Your Children About Sex 2 • the Complex Emotions That Can Go Along with Having Sex

Nearly all (97%) U.S. homes own at least one television. TV is part of most of our daily lives, The and most people have a favorite show…or three or four. TV shows are filled with story lines related to sexuality, relationships, and Talk Show reproductive health — everything from sex Using TV to Talk with Your and pregnancy to unhealthy relationships and Children about Sex gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender issues. Watching TV with your children can help you have honest conversations about these topics. You can use storylines to spark conversations and find out what your child thinks and how they might behave if they were faced with the same situation. You can also share your values, expectations, and hopes for them. STEP 1 Find out which shows your kids are watching and figure out a time to watch with them when you won’t be distracted. Ask open-ended questions about what they’re watching instead of yes/no questions to get a conversation going. Here are some general questions you can start with: • What is this show about? What do you like about it? • What do you think about what’s happening in the show right now? • How realistic are the situations in the show? Do you know anyone in a similar situation? If so, how are they handling it? What do you think about how they are handling it? What would you do? • Which relationships in the show are healthy and which are unhealthy, and why? STEP 2 Get more specific about what’s happening on the show, and listen carefully to what your children say. -

The Transom Review February, 2003 Vol

the transom review February, 2003 Vol. 3/Issue 1 Edited by Sydney Lewis Gwen Macsai’s Topic About Gwen Macsai Gwen Macsai is an award winning writer and radio producer for National Public Radio. Her essays have been heard on All Things Considered, Morning Edition and Weekend Edition Saturday with Scott Simon since 1988. Macsai is also the creator of "What About Joan," starring Joan Cusack and author of "Lipshtick," a book of humorous first person essays published by HarperCollins in February of 2000. Born and bred in Chicago (south shore, Evanston), Macsai began her career at WBEZ-FM and then moved to Radio Smithsonian at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. After working for NPR for eight years she moved to Minneapolis, MN where "Lipshtick" was born, along with the first of her three children. Then, one day as she tried to wrangle her smallish-breast-turned-gigantic- snaking-fire-hose into the mouth of her newborn babe, James L. Brooks, (Producer of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, Taxi, The Simpsons and writer of Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News and As Good As It Gets), called. He had just heard one of her essays on Morning Edition and wanted to base a sitcom on her work. In 2000, "What About Joan" premiered. The National Organization for Women chose "What About Joan" as one of the top television shows of that season, based on its non- sexist depiction and empowerment of women. Macsai graduated from the University of Illinois and lives in Evanston with her husband and three children. Copyright 2003 Atlantic Public Media Transom Review – Vol. -

Andy Robertson

ANDY ROBERTSON SELECTED CREDIT LIST TITLE / DESCRIPTION CREDIT COMPANY / NETWORK Strive Executive Producer / Radley Studios / Perfect Storm Director / Showrunner YouTube ½ hour documentary series about Refugee Olympians Everest: The First Ascent Executive Producer / MAK Pictures Showrunner Discovery Channel 2-Hour documentary special Free Meek Co-Executive Producer IPC / ROC Nation Amazon Studios 5-part documentary series This Giant Beast That Is The Global Economy Co-Executive Producer IPC / Gary Sanchez Productions Amazon Studios Comedy-documentary series Eat. Race. Win Co-Executive Producer Junto Entertainment Amazon Studios ½-Hour sports / food documentary series Cold Case Files Executive Producer AMPLE, Blumhouse Television Post-Showrunner A&E 10 x 1-Hour true-crime documentary series Life of Godfrey Co-Executive Producer MTV Pilot Presentation about a family of Mormon Daredevils Believer, with Reza Aslan Co-Executive Producer Whalerock Industries, BoomGen CNN 1-hour documentary series about world religions The Agent Co-Executive Producer Herzog & Co. Showrunner Esquire TV 1-hour documentary series about NFL Agents The Short Game Co-Executive Producer Goodbye Pictures Post-Showrunner Esquire TV 1-hour documentary series about child golf prodigies Every Street United Executive Producer Mandalay Sports Post-Showrunner Xbox Entertainment Studios ½-Hour Documentary Series about International Street Soccer The Internet’s Own Boy: The Aaron Swartz Story Editor Luminant Media Feature Documentary about the life & death of an internet activist Participant Media Loredana, Esq. Producer / Go Go Luckey Entertainment Supervising Editor Sundance Channel 1-hour reality-based legal procedural series Internal Affairs (Pilot) Producer / Editor Fox Television Productions BET Documentary series – Cops Investigate Cops Raising McCain (Pilot Episode) Producer / Editor Go Go Luckey Entertainment Pivot Talk Show / Reality hybrid. -

Online Partisan Media, User-Generated News Commentary, and the Contested Boundaries of American Conservatism During the 2016 US Presidential Election

The London School of Economics and Political Science Voices of outrage: Online partisan media, user-generated news commentary, and the contested boundaries of American conservatism during the 2016 US presidential election Anthony Patrick Kelly A thesis submitted to the Department of Media and Communications of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2020 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD de- gree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other per- son is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99 238 words. 2 Abstract This thesis presents a qualitative account of what affective polarisation looks like at the level of online user-generated discourse. It examines how users of the American right-wing news and opinion website TheBlaze.com articulated partisan oppositions in the site’s below-the-line comment field during and after the 2016 US presidential election. To date, affective polarisation has been stud- ied from a predominantly quantitative perspective that has focused largely on partisanship as a powerful form of social identity. -

Broadcast Scripts

BROADCAST SCRIPTS ACCT-BVP1-5. Students will identify and create different script types. a. Identify scripts by format. b. List steps leading to the development of various type ( i.e., news and/or sitcom) broadcast scripts. c. Define terminology used in broadcast scriptwriting. d. Plan and produce a storyboard. e. Write broadcast scripts as assigned. Introduction Too many students experience anxiety when they hear the word “writing.” One of the best things that can be said about television scriptwriting is that it bears little resemblance to the writing style required for academic courses. Although scriptwriting is relatively simple to do, good scriptwriting takes talent and skill Program Formats A script is an entire program committed to paper. It includes dialog, music, camera angles, stage direction, camera direction, computer graphics (CG) notations, and all other items that the director or script writer feels should be noted. There are many different kinds of television programs, each with unique requirements of the script. Most programs fit into one of the following categories: •Lecture. The lecture program format is the easiest format to shoot; the talent speaks and the camera shoots almost entirely in a medium close-up. All that is needed for this format is the talent, a camera, and a podium for the talent to stand behind. Other names for the lecture format are BTF (big talking face) or talking head. This format has the lowest viewer retention and is often the mark of an amateur. •Lecture/Demonstration. The lecture/demonstration format lends itself to the numerous cooking shows, how-to shows, and infomercials seen on television today. -

The Political Content of Late-Night Talk Show Monologues Or

It May be Funny, But Is It True: The Political Content of Late-Night Talk Show Monologues or Everything I Learned About Politics I Learned From Jay Leno Lindsey Duerst, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Glory Koloen, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Geoff Peterson, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Prepared for delivery at the American Political Science Association conference in San Francisco, CA, August 29 through September 2, 2001. Abstract As the influence of the media on political campaigns continues to grow, new media sources such as late-night talk shows have grown in importance and stature. We examined the content of the monologues for the three most popular late-night talk show hosts (Letterman, Leno, and Conan O’Brien) to see what political information was presented to the audience. We found that the vast majority of the humor was negative and targeted at the character of the candidates. There was an amazing lack of information about any of the substantive issues in the campaign with the exception of the death penalty. We also found that only one of the three hosts showed a consistent bias towards one party, while the other two remained ideologically neutral. Overall, the results indicate that the average late-night viewer would be likely to be uninformed and generally negative given the information provided by the three hosts. It May be Funny, But Is It True: The Political Content of Late-Night Talk Show Monologues or Everything I Learned About Politics I Learned From Jay Leno Lindsey Duerst, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Glory Koloen, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Geoff Peterson, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire “When Gore accused Bush of being a tool of the big drug companies, Bush responded, ‘I am not a tool of the pharmaceutical industry. -

ANDREW SMITH 220 East 72ND Street #7F New York, NY 10021 (917) 747-8248(Cell) [email protected] Williams College

ANDREW SMITH 220 East 72ND Street #7F New York, NY 10021 (917) 747-8248(cell) [email protected] Williams College FEATURES Main Event (with Gail Parent) Stir Crazy (original treatment & script) Who's That Girl? ("Slammer") (With Ken Finkelman) Harlem Nights (re-write) Look Who's Talking Now (treatment draft) TELEVISION MOVIES Maid For Each Other (NBC) TELEVISION (hour episodes) Touched By An Angel (2) Chicago Hope (1) The Practice (1) (with Ed Redlich) New York Undercover (1) (Story) TELEVISION (half-hour staff) On Our Own (Supervising Producer) The New Love American Style (Story Editor) TELEVISION (half-hour pilots) That Show Starring Joan Rivers Sheila! (with Gail Parent) (CBS) The Sid Caesar Show (with Sam Denoff)(CBS) STAT (ABC) Politically Incorrect (HBO) (with Chris Kelly) Love, Hate, & Joy (ABC) Head Writer TELEVISION (half hour episodes) On Our Own (4) Bob Newhart Show (3) The New Love American Style (2) STAT (3) Married.....With Children (1) TELEVISION (variety & talk staff) The Tonight Show That Show Starring Joan Rivers (Pilot and Launch) Public Broadcast Laboratory The David Frost Show The Merv Griffin Show (Head Writer) Saturday Night Live With Howard Cosell (ABC) (pilot and staff)) Saturday Night Live (NBC) (Head Writer) (3 Emmy Nominations) The News Is The News The New Love American Style (Story Editor) Friday Night Videos SAJAK (talk show pilot) (Writer/Producer) Politically Incorrect (Writer/Creative Consultant) El Barrio USA (Writer/Co/Director) Live From Queens NY-GO The View (10 Emmy Nominations, 2 Emmy Awards) (15 years) Love, Hate, And Joy (Head Writer) Topic A - With Tina Brown (Pilot) Primetime View Special The View Oscar Special SPECIALS Take Me Home Again The Playboy Roller Disco and Pajama Party The 43rd Annual Emmy Awards The Daytime Emmy Awards Roseanne's Hanukkah Special Disney Channel 25th Anniversary Celebration (3 half Hours) The 25th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards Disney World Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Special Tyson Vs.