Imperative Negatives in Earlier Southern Min and Their Later Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: Morphology and Syntax*

Breaking Down the Barriers, 785-816 2013-1-050-037-000234-1 Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: * Morphology and Syntax Hilary Chappell (曹茜蕾) EHESS In Chinese languages, when a direct object occurs in a non-canonical position preceding the main verb, this SOV structure can be morphologically marked by a preposition whose source comes largely from verbs or deverbal prepositions. For example, markers such as kā 共 in Southern Min are ultimately derived from the verb ‘to accompany’, pau11 幫 in many Huizhou and Wu dialects is derived from the verb ‘to help’ and bǎ 把 from the verb ‘to hold’ in standard Mandarin and the Jin dialects. In general, these markers are used to highlight an explicit change of state affecting a referential object, located in this preverbal position. This analysis sets out to address the issue of diversity in such object-marking constructions in order to examine the question of whether areal patterns exist within Sinitic languages on the basis of the main lexical fields of the object markers, if not the construction types. The possibility of establishing four major linguistic zones in China is thus explored with respect to grammaticalization pathways. Key words: typology, grammaticalization, object marking, disposal constructions, linguistic zones 1. Background to the issue In the case of transitive verbs, it is uncontroversial to state that a common word order in Sinitic languages is for direct objects to follow the main verb without any overt morphological marking: * This is a “cross-straits” paper as earlier versions were presented in turn at both the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, during the joint 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics and 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics, held in Taipei in May 25-29, 2006 and also at an invited seminar at the Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing on 23rd October 2006. -

Language Contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese

20140303 draft of : de Sousa, Hilário. 2015a. Language contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese. In Chappell, Hilary (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic languages, 157–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Do not quote or cite this draft. LANGUAGE CONTACT IN NANNING — FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF NANNING PINGHUA AND NANNING CANTONESE1 Hilário de Sousa Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, École des hautes études en sciences sociales — ERC SINOTYPE project 1 Various topics discussed in this paper formed the body of talks given at the following conferences: Syntax of the World’s Languages IV, Dynamique du Langage, CNRS & Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2010; Humanities of the Lesser-Known — New Directions in the Descriptions, Documentation, and Typology of Endangered Languages and Musics, Lunds Universitet, 2010; 第五屆漢語方言語法國際研討會 [The Fifth International Conference on the Grammar of Chinese Dialects], 上海大学 Shanghai University, 2010; Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Conference 21, Kasetsart University, 2011; and Workshop on Ecology, Population Movements, and Language Diversity, Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2011. I would like to thank the conference organizers, and all who attended my talks and provided me with valuable comments. I would also like to thank all of my Nanning Pinghua informants, my main informant 梁世華 lɛŋ11 ɬi55wa11/ Liáng Shìhuá in particular, for teaching me their language(s). I have learnt a great deal from all the linguists that I met in Guangxi, 林亦 Lín Yì and 覃鳳餘 Qín Fèngyú of Guangxi University in particular. My colleagues have given me much comments and support; I would like to thank all of them, our director, Prof. Hilary Chappell, in particular. Errors are my own. -

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: the Case of Disposal Constructions in Sinitic Languages

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: The case of disposal constructions in Sinitic languages Hilary Chappell 1. Introduction 1.1. The issue Although China has a long tradition in the compilation of rhyme dictionar- ies and lexica, it did not develop its own tradition for writing grammars until relatively late.1 In fact, the majority of early grammars on Chinese dialects, which begin to appear in the 17th century, were written by Europe- ans in collaboration with native speakers. For example, the Arte de la len- gua Chiõ Chiu [Grammar of the Chiõ Chiu language] (1620) appears to be one of the earliest grammars of any Sinitic language, representing a koine of urban Southern Min dialects, as spoken at that time (Chappell 2000).2 It was composed by Melchior de Mançano in Manila to assist the Domini- cans’ work of proselytizing to the community of Chinese Sangley traders from southern Fujian. Another major grammar, similarly written by a Do- minican scholar, Francisco Varo, is the Arte de le lengua mandarina [Grammar of the Mandarin language], completed in 1682 while he was living in Funing, and later posthumously published in 1703 in Canton.3 Spanish missionaries, particularly the Dominicans, played a signifi- cant role in Chinese linguistic history as the first to record the grammar and lexicon of vernaculars, create romanization systems and promote the use of the demotic or specially created dialect characters. This is discussed in more detail in van der Loon (1966, 1967). The model they used was the (at that time) famous Latin grammar of Elio Antonio de Nebrija (1444–1522), Introductiones Latinae (1481), and possibly the earliest grammar of a Ro- mance language, Grammatica de la Lengua Castellana (1492) by the same scholar, although according to Peyraube (2001), the reprinted version was not available prior to the 18th century. -

The Modal System in Hainan Min*

Article Language and Linguistics The Modal System in Hainan Min* 15(6) 825–857 © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1606822X14544622 Hui-chi Lee lin.sagepub.com National Cheng Kung University This paper explores the idiosyncratic features of the modal system in Hainan Min (based on data collected through fieldwork). The lexical items are firstly presented in four categories of modal types, including epistemic, deontic, circumstantial and bouletic modals. The modal hierarchy is built upon data with multiple modals: epistemic > deontic > dynamic. The last part of the paper introduces the negative modal forms in Hainan Min. The scopal interaction between negation and modals is also discussed. The negation always scopes over modals. Key words: Hainan Min, modal hierarchy, modality, scopal interaction 1. Introduction The present study focuses on the modal structures in Hainan Min, which has rarely been explored in previous studies. As a branch of the Min dialects, Hainan Min is a Chinese dialect spoken on Hainan Island. While it is mostly assumed to be a dialect of Southern Min, Hainan Min and other dialects of Southern Min are barely mutually intelligible. There is not only a phonetic separation,1 but also lexical and syntactical divergences between Hainan Min and other Chinese dialects. For example, the Mandarin disposal marker ba corresponds to ɓue in Hainan Min. Unlike Mandarin ba, ɓue cannot take an animate complement and it can colloquially serve as a verb indi- cating ‘hold’. Unlike ka in Southern Min, ɓue does not perform multiple functions; for example it cannot serve as a benefactive marker. -

LANGUAGE CONTACT and AREAL DIFFUSION in SINITIC LANGUAGES (Pre-Publication Version)

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES (pre-publication version) Hilary Chappell This analysis includes a description of language contact phenomena such as stratification, hybridization and convergence for Sinitic languages. It also presents typologically unusual grammatical features for Sinitic such as double patient constructions, negative existential constructions and agentive adversative passives, while tracing the development of complementizers and diminutives and demarcating the extent of their use across Sinitic and the Sinospheric zone. Both these kinds of data are then used to explore the issue of the adequacy of the comparative method to model linguistic relationships inside and outside of the Sinitic family. It is argued that any adequate explanation of language family formation and development needs to take into account these different kinds of evidence (or counter-evidence) in modeling genetic relationships. In §1 the application of the comparative method to Chinese is reviewed, closely followed by a brief description of the typological features of Sinitic languages in §2. The main body of this chapter is contained in two final sections: §3 discusses three main outcomes of language contact, while §4 investigates morphosyntactic features that evoke either the North-South divide in Sinitic or areal diffusion of certain features in Southeast and East Asia as opposed to grammaticalization pathways that are crosslinguistically common.i 1. The comparative method and reconstruction of Sinitic In Chinese historical -

South-East Asia Second Edition CHARLES S

Geological Evolution of South-East Asia Second Edition CHARLES S. HUTCHISON Geological Society of Malaysia 2007 Geological Evolution of South-east Asia Second edition CHARLES S. HUTCHISON Professor emeritus, Department of geology University of Malaya Geological Society of Malaysia 2007 Geological Society of Malaysia Department of Geology University of Malaya 50603 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Geological Society of Malaysia ©Charles S. Hutchison 1989 First published by Oxford University Press 1989 This edition published with the permission of Oxford University Press 1996 ISBN 978-983-99102-5-4 Printed in Malaysia by Art Printing Works Sdn. Bhd. This book is dedicated to the former professors at the University of Malaya. It is my privilege to have collabo rated with Professors C. S. Pichamuthu, T. H. F. Klompe, N. S. Haile, K. F. G. Hosking and P. H. Stauffer. Their teaching and publications laid the foundations for our present understanding of the geology of this complex region. I also salute D. ]. Gobbett for having the foresight to establish the Geological Society of Malaysia and Professor Robert Hall for his ongoing fascination with this region. Preface to this edition The original edition of this book was published by known throughout the region of South-east Asia. Oxford University Press in 1989 as number 13 of the Unfortunately the stock has become depleted in 2007. Oxford monographs on geology and geophysics. -

Borrowed Words from Japanese in Taiwan Min-Nan Dialect

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 3, No. 2; June 2016 The Difference between Taiwan Min-nan Dialect and Fujian Min-nan Dialect: Borrowed Words from Japanese in Taiwan Min-nan Dialect Ya-Lan Tang Department of English Tamkang University 11F., No.3, Ln. 65, Yingzhuan Rd., Tamsui Dist., New Taipei City 25151, Taiwan Abstract Southern Min dialect (also called Min-nan or Hokkien) in Taiwan is usually called ‘Taiwanese.’ Though there are many other dialects in Taiwan, such as Hakka, Mandarin, aboriginal languages, people speak Min-nan are the majority in Taiwan society. It becomes naturally to call Southern Min dialect as Taiwanese. Taiwanese Min-nan dialect though came from Mainland China; however, Min-nan dialect in Taiwan is a little different from Min-nan dialect in Fujian, China. Some words which are commonly used in Taiwanese Min-nan dialect do not see in Min- nan dialect in Fujian. In this paper the writer, choose some Taiwanese Min-nan words which are actually from Japanese as materials to discuss the difference between Taiwanese Min-nan dialect and Min-nan in Fujian. Key Words: Taiwanese Min-nan, Fujian Min-nan, borrowed words. 1. Introduction Taiwanese Min-nan has been used in Taiwan for hundreds of years, and it is now different from its origin language, Fujian Min-nan dialect. In order to clarify the difference between Taiwan Min-nan dialect and Min-nan dialect in Fujian, the first point to make is the identity of Taiwanese people themselves. Language and identity cannot be separated. Therefore, based on this point of view, this paper is going to discuss three questions below: 1. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 205 The 2nd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2018) The Preservation of Hokkien Yingqiu Chen Xiaoxiao Chen* School of English for International Business School of English for International Business Guangdong University of Foreign Studies Guangdong University of Foreign Studies Guangzhou, China Guangzhou, China *Corresponding author Abstract—Hokkien in recent years has witnessed a gradual To begin with, formed by migration of people in the decrease in speaking population, which will accelerate the Central Plain, Hokkien is an ancient Chinese language that process of language endangerment. However, it is unaffordable can date back to more than 1000 years ago. On account of not to cease Hokkien’s decline because Hokkien possesses this, there are a large number of ancient vocabularies in elements that distinguish it from others. From linguistic, Hokkien; besides, the tones and phonetics of ancient Chinese cultural and community-based views, it is necessary to can be found in today’s Hokkien. With the valuable language maintain Hokkien so that it will not disappear from any information contained in Hokkien, quite many linguists, speaker’s tongue. To achieve that, measures against its decay home and abroad, especially those who specialize in Chinese should be executed and reinforced, which will involve 4 types languages, believe that it is the “living fossil” of ancient of aspects, namely personal, societal, governmental and cross- Chinese language [5]. national. With these measures coming into effect, the revitalization of Hokkien will take place in a near future. Second, Hokkien once served as lingua franca for people in Taiwan and Southeast Asia, as a result of its witnessing Keywords—Hokkien; preservation; measures the movement of people from Fujian to those places and how these newcomers fought for the lives in new lands. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Tongue-Tied Taiwan: Linguistic Diversity and Imagined Identities at the Crossroads of Colonial East Asia

Tongue-Tied Taiwan: Linguistic Diversity and Imagined Identities at the Crossroads of Colonial East Asia Yu-Chen Eathan Lai This thesis has been submitted on this day of April 15, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the NYU Global Liberal Studies Bachelor of Arts degree. 1 Yu-Chen Eathan Lai, “Tongue-Tied Taiwan: Linguistic Diversity and Imagined Identities at the Crossroads of Colonial East Asia,” Undergraduate Thesis, New York University, 2018. A history of repeated colonization and foreign occupation created in Taiwan a severe language gap spanning three generations, and left its people in an anxious search for the island’s “linguistic” and “national” identity. Taiwanese speakers of indigenous Austronesian languages and Chinese dialects such as Hokkien and Hakka have historically endured the imposition of two different national languages: Japanese since 1895 and Mandarin since 1945. In this project, I draw on anthropological perspectives and media analysis to understand the ideologies and symbols vested upon different languages and codes that still circulate within different media today. My research primarily investigates an autoethnographic report on a family history, several museum and gallery exhibits, as well as two different documentaries, all centered on Hokkien speakers in Taiwan. I argue that a future generation’s narrative construction of an authentic Taiwanese identity must be rooted in the island’s past and present reality of linguistic and cultural diversity. Keywords: Taiwan, Oral History, Colonial -

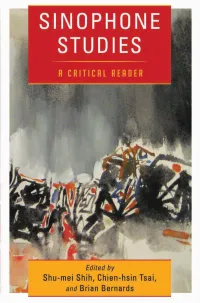

Untitled by Hung Chang (C

SINOPHONE STUDIES Global Chinese Culture GLOBAL CHINESE CULTURE David Der-wei Wang, Editor Michael Berry, Speaking in Images: Interviews with Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers Sylvia Li-chun Lin, Representing Atrocity in Taiwan: The 2/28 Incident and White Terror in Fiction and Film Michael Berry, A History of Pain: Literary and Cinematic Mappings of Violence in Modern China Alexander C. Y. Huang, Chinese Shakespeares: A Century of Cultural Exchange SINO ______________PHONE STUDIES A Critical Reader edited by SHU-MEI SHIH, CHIEN-HSIN TSAI, and BRIAN BERNARDS Columbia University Press New York Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Chiang Ching- kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and Council for Cultural Affairs in the publication of this book. Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex cup.columbia.edu Copyright © 2013 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sinophone studies : a critical reader / edited by Shu-mei Shih, Chien-hsin Tsai, and Brian Bernards. p. cm.—(Global Chinese culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-231-15750-6 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-231-15751-3 (pbk.)— ISBN 978-0-231-52710-1 (electronic) 1. Chinese diaspora. 2. Chinese–Foreign countries–Ethnic identity. 3. Chinese–Foreign countries– Intellectual life. 4. National characteristics, Chinese. I. Shi, Shumei, 1961–II. Tsai, Chien-hsin, 1975– III. Bernards, Brian. DS732.S57 2013 305.800951–dc23 2012011978 Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. This book was printed on paper with recycled content.