Flora Text 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEATH of TRU Have Him Around the House Again

A Genuine Pioneer Celebrates Birthday lif In hi him ti up to the ictive n- his on Febru- liisJ I COODBGE TAKEN BY DEATH JjOTfti-'fc—it T©L s STORIES DIES AT * PORT HOME. SHE WAS BORN _KlV&t) 18Q$45 __*•___-. i^uiff t/3* *JU Wrote "Katy Did" Keriea and Oth er 'Well-Known Children'. Book. —Father Wa. a Promi nent Educator. Henry Byal band- of the thelr borne, on East Sam [Specl.l Dispatch from the New York Sun.] NEWPORT, R. I.. April 9.—Miss (1 Willi li Sarah Chauncey Woolsey, better nd trailing known as Susan Coolidge, a writer of •in a (Tali children's stories, died suddenly of ' ill fur IV. heart disease at her home here to-day. Mr. and Mrs. i She was sixty years of age and | Itltlftll flo' 'ill- a daughter of the late John F. V tend their sey, of New Haven. Iforn • h Chaum wa« horn bly realising that the illness * gan reading law with the Hon. 1 in Cls i lS4b. Her family <n with the law LaBlond, and was admitted to the bar in of th' "ok, one of her uncles, flrm, which had been iniiintiiineil during 1869. Before this, he served two years Dwight Woolsey, win • and went to his oil as an enrolling clerk in the house of the Ohio general assembly. ,n educator at the head borne at Wauseon, in the hope that the Mr. Touvelle began the practice of of Yalo University. A cousin of "Su- change woud benefit Lira. Mrs. -

The Glass Firms at Greenfield, Indiana

The Glass Firms at Greenfield, Indiana Bill Lockhart, Beau Schriever, Bill Lindsey, and Carol Serr When Louis Hollweg – a jobber in crockery, tableware, lamps, and fruit jars – decided to branch out into the glass container manufacturing business in 1890, he built a glass factory that became the scene for five different operators over a 30-year period. Throughout most of its existence, the plant concentrated on fruit jar production, making a variety of jars that can be directly traced to the factory, especially to the Greenfield Fruit Jar & Bottle Co. Once the big- name firms (Ball Brothers and Owens) took over, the plant’s days were numbered. Histories Hollweg & Reese, Indianapolis, Indiana (1868-ca. 1914) Louis Hollweg and Charles E. Reese formed the firm of Hollweg & Reese in 1868. Located at 130-136 South Meridian Street, Indianapolis, Indiana, the company was a direct importer and jobber in crockery, pressed and blown tableware, lamps, lamp paraphernalia, and other fancy goods (Figure 1). After the death of Resse in 1888, Hollweg continued to use the Hollweg & Reese name. The last entry we could find for the firm was in 1913, so Hollweg probably disbanded the firm Figure 1 – Hollweg & Reese (Hyman 1902:354) (or sold out) ca. 1914 – a few years after he exited the glass business (Hyman 1902:354-355; Indiana State School for the Deaf 1914:90). Containers and Marks Although the firm’s main product list did not include containers, Hollweg & Reese apparently began carrying its own line of fruit jars by the 1870s, when William McCully & Co. made the Dictator, a jar similar to a grooved-ring, wax-sealer that was embossed with the 469 Hollweg & Reese name. -

The-Mcgregor-Story

The Story Chapter 1 The McGregor Story TThe McGregor story starts in 1877 when Amasa Stone, the legendary capitalist and preeminent Cleveland philanthropist, and his wife, Julia, built and endowed one of the first private organizations in Cleveland specifically for the care of seniors — the Home for Aged Women, later to be renamed the Amasa Stone House, on what is now East 46th Street and Cedar Avenue. After training as a carpenter and building contractor in his native Massachusetts and moving to Cleveland in 1850, Amasa turned his considerable ambition to transportation. He built the Lake Shore Railroad, which ran between Erie, Pennsylvania and Cleveland as part of the New York Central. During the post-Civil War industrial boom, he found himself among America’s elite railroad builders. He also worked with his brother-in- law, William Howe, in designing a truss bridge to sustain heavy loads of rail cargo over short spans, like small gullies and ravines. Over the years Amasa became one of Cleveland’s leading business figures, eventually moving to a mansion on Euclid Avenue — dubbed “Millionaires Row” by the press — near a 3 Y R A R B I L Y T I S R E V I N U E T A T S D Tank wagons such as this, built N A L E V by the Standard Oil Company E L C , S in Cleveland in 1911, were N O I T C E standard equipment throughout L L O C the world in the petroleum L A I C E P industry. -

The Mcgregor Story

The Story Chapter 1 The McGregor Story TThe McGregor story starts in 1877 when Amasa Stone, the legendary capitalist and preeminent Cleveland philanthropist, and his wife, Julia, built and endowed one of the first private organizations in Cleveland specifically for the care of seniors — the Home for Aged Women, later to be renamed the Amasa Stone House, on what is now East 46th Street and Cedar Avenue. After training as a carpenter and building contractor in his native Massachusetts and moving to Cleveland in 1850, Amasa turned his considerable ambition to transportation. He built the Lake Shore Railroad, which ran between Erie, Pennsylvania and Cleveland as part of the New York Central. During the post-Civil War industrial boom, he found himself among America’s elite railroad builders. He also worked with his brother-in- law, William Howe, in designing a truss bridge to sustain heavy loads of rail cargo over short spans, like small gullies and ravines. Over the years Amasa became one of Cleveland’s leading business figures, eventually moving to a mansion on Euclid Avenue — dubbed “Millionaires Row” by the press — near a 3 Y R A R B I L Y T I S R E V I N U E T A T S D Tank wagons such as this, built N A L E V by the Standard Oil Company E L C , S in Cleveland in 1911, were N O I T C E standard equipment throughout L L O C the world in the petroleum L A I C E P industry. -

MINERAL RESOURCES the West Republic

STATE OF MICHIGAN. The Argyle Mine ...........................................................42 The Republic ................................................................42 MINERAL RESOURCES The West Republic.......................................................45 BY The Columbia Mine ......................................................45 CHARLES. D. LAWTON, A. M. C. E., The Fremont Iron Co....................................................46 COMMISSIONER OF MINERAL STATISTICS. The Milwaukee Mine ....................................................46 BY AUTHORITY The Wheeling Mine ......................................................47 The McComber Mine....................................................47 LANSING: The Manganese Mine ..................................................48 THORP & GODFREY, STATE PRINTERS AND BINDERS. Bay State......................................................................48 1886. Saginaw Mining Co. .....................................................48 The Salisbury Mine ......................................................48 The Pittsburgh And Lake Superior Iron Co..................49 Contents The Wheat Mine...........................................................50 The Taylor Mine ...........................................................51 INTRODUCTORY NOTE .................................................. 1 The Swanzy Mine.........................................................51 THE IRON INDUSTRY...................................................... 2 The Menominee Range Mines.....................................51 -

2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy

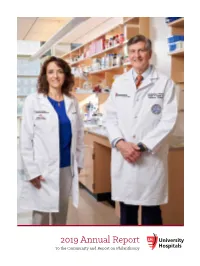

2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy Cover: Leading UH research on COVID-19, Grace McComsey, MD, Vice President of Research and Associate Chief Scientific Officer, UH Clinical Research Center, Rainbow Babies & Children's Foundation John Kennell Chair of Excellence in Pediatrics, and Division Chief of Infectious Diseases, UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital; and Robert Salata, MD, Chairman, Department of Medicine, STERIS Chair of Excellence in Medicine and and Master Clinician in Infectious Disease, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and Program Director, UH Roe Green Center for Travel Medicine and Global Health, are Advancing the Science of Health and the Art of Compassion. Photo by Roger Mastroianni The 2019 UH Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy includes photographs obtained before Ohio's statewide COVID-19 mask mandate. INTRODUCTION REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY 5 Letter to Friends 38 Letter to our Supporters 6 UH Statistics 39 A Gift for the Children 8 UH Recognition 40 Honoring the Philanthropic Spirit 41 Samuel Mather Society UH VISION IN ACTION 42 Benefactor Society 10 Building the Future of Health Care 43 Revolutionizing Men's Health 12 Defining the Future of Heart and Vascular Care 44 Improving Global Health 14 A Healing Environment for Children with Cancer 45 A New Game Plan for Sports Medicine 16 UH Community Highlights 48 2019 Endowed Positions 18 Expanding the Impact of Integrative Health 54 Annual Society 19 Beating Cancer with UH Seidman 62 Paying It Forward 20 UH Nurses: Advancing and Evolving Patient Care 63 Diamond Legacy Society 22 Taking Care of the Browns. -

History Notes Phone: 216.368.2380 Fax: 216.368.4681 2013-2014

Department of History Case Western Reserve 10900 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, Oh 44106-7107 History Notes Phone: 216.368.2380 Fax: 216.368.4681 2013-2014 www.case.edu/artsci/hsty Editors: John Grabowski, Jesse Tarbert, and John Baden Report from the Department Chair Have I mentioned that I really like this department? It only gets better. In the Spring of this year, we added a new faculty member, Ananya Dasgupta, who recently completed her Ph.D. in the South Asian Studies program at the Univer- sity of Pennsylvania. She is the first tenure-track specialist in that region to teach in this department. We also have a new Department Assistant, Bess Weiss; she and Emily Sparks are proving to be a great team in the department office. History Associates continues to support the graduate program with fel- lowships, and to add to the intellectual life of the department with the annual Ubbelohde lecture, which was given this year by Janice Radway of Northwest- ern University. As you will see as you read the rest of this newsletter, our faculty and Jonathan Sadowsky students continue to be extremely active in publishing books and articles, and winning major fellowships. It is a privilege to work here. History Department Welcomes Post-Doctoral Fellowship Recipient, Dr. Shannen Dee Williams Dr. Shannen Dee Williams is the 2013-2014 Postdoctoral Fellow in African-American studies at Case Western Re- serve University. She earned her Ph.D. in African-American and United States history and a graduate certificate in women's and gender studies from Rutgers University on May 19, 2013. -

Download Steel on the Bottom: Great Lakes Shipwrecks Free Ebook

STEEL ON THE BOTTOM: GREAT LAKES SHIPWRECKS DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Frederick Stonehouse | 215 pages | 30 Apr 2006 | AVERY COLOR STUDIOS | 9781892384355 | English | United States ISBN 13: 9781892384355 Iced up and slowly sank in a storm after passing through the Straits of Mackinac. The freighter went down in a storm on November 10,taking with her the Steel on the Bottom: Great Lakes Shipwrecks crew of The Isaac M. Cox as well as many other area wrecks. Due to its economic success it became the prototype for the Great Lakes bulk freighter, a very large and important class of commercial ship that made possible the cheap transport of raw materials for the steel industry, including iron ore, coal and limestone. The ship sank immediately and the four crew on board drowned. Lighthouse Tales will appeal greatly to anyone interested in the wonders of the Great Lakes, historians, sailors, lighthouse fanatics and people looking for a roaring good story. A bulk freighter that sank off Michigan Island. This book is sure to please both the Great Lakes history and shipwreck buff. During this early maritime history, many ships departed port but failed to arrive at their destination. However, historian Mark Thompson, the author of Graveyard of the Lakes has estimated that there are over shipwrecks on the bottom of the Great Lakes. When a harbor tugboat directed the Hadley to divert to Superior harbor, the captain of the Hadley ordered an immediate turn to port, failing to notice the direction of the Wilson or to blow the required whistle signals. It is only available at various locations stores in the city or drop me an email and I am sure we can work out a deal. -

First Presbyterian ("Old Stone") HABS No. °-2L24 Church in Cleveland . J1'^" ' 91 Public Square, Northwest Corner OH/0 Rockwell Ave

First Presbyterian ("Old Stone") HABS No. °-2l24 Church in Cleveland . j1'^" ' 91 Public Square, northwest corner OH/0 Rockwell Ave. and Ontario St. \<&-ClW Cleveland Cuyahoga County \0 - Ohio PHOTOGRAPHS WtlTTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 HISTOEIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. 0-212^ • FIRST PRESBYTERIAN ("OLD STONE") CHURCH IN CLEVELAND, OHIO .j^r'10 to Location: 91 Public Square, northwest corner Rockwell Ave. and Ontario St., Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Present Owner: The First Presbyterian Society, Cleveland, Ohio. Present Occupant: The First Presbyterian Society in Cleveland, which was established 1820, when the population of Cleveland was about 150. Present Use: Church sanctuary. Statement of Preceded only a few months by Trinity Church Significance: (Episcopal), "The Old Stone Church" is Cleveland's second oldest. Established under the "Plan of Union" of the Presbyterian and Congregational Churches, it is the Mother Church in Cleveland of the many Presbyterian and Congregational Churches which followed. It is the oldest surviving building in the central city. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION • A. Physical History: 1. Original and subsequent owners: About 1830 the site was purchased for $^00.00 with the gifts of ten early settlers There is no record of any use of this site (for building purposes) prior to 1832, when the first church building (55' x 80') was erected. This original gray sandstone structure had Tuscan pilasters. It was the first stone building used exclusively as a church in Cleveland. Eventually it was known as "The Stone Church," and later "The Old Stone Church" as the sandstone darkened. -

Olmsted 200 Bicentennial Notes About Olmsted Falls and Olmsted Township – First Farmed in 1814 and Settled in 1815 Issue 86 July 1, 2020

Olmsted 200 Bicentennial Notes about Olmsted Falls and Olmsted Township – First Farmed in 1814 and Settled in 1815 Issue 86 July 1, 2020 Contents Olmsted’s First Railroad Connected West View to the World 1 OFHS Teacher Uses Olmsted 200 in Geology Lesson 10 June Stories Evoke Reader’s Memories 11 Still to Come 12 Olmsted’s First Railroad Connected West View to the World In 1850, a new sight and sound broke through the quiet forests and farm fields in the southeastern corner of Olmsted Township known as West View. Over the past 170 years, such sights and sounds have become common features of Olmsted life since that inaugural trip of a train on the first section of the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad. Accounts differ over exactly when in 1850 that first train chugged its way through West View, but there is no dispute that railroads affected Olmsted’s development and daily life ever since then. Some reports say the first train ran on This right-of-way in southern Olmsted Monday, July 1, with a load of dignitaries, but Falls is where the first set of railroad other reports say that first train actually ran as tracks in Olmsted Township went into early as Thursday, May 16, 1850. Walter use in 1850. Holzworth, in his 1966 book on Olmsted history, wrote that “a small but jubilant crowd” witnessed the first train to pass through any portion of Olmsted Township on July 1, 1850. He wrote further: A brass trimmed wood burning locomotive with no cowcatcher or head lights, pulling a box like car piled high with fire wood, a small tank car as water tender, and three small open passenger cars with curtains rolled up and its seats filled with dignitaries, started from Cleveland and sped along at the amazing speed of fifteen to twenty miles per hour. -

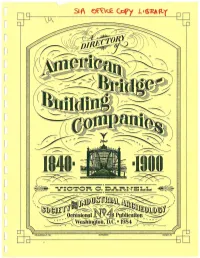

SIA Occasional No4.Pdf

.. --;- 1840· MCMLXXXIV THE SOCIETY FOR INDUSllUAL ARCBE<LOGYpromotes the study of the physical survivals of our industrial heritage. It encourages and sponsors field investigations, research, recording, and the dissemination and exchange of information on all aspects of industrial archeology through publications, meetings, field trips, and other appropriate means. The SIA also seeks to educate the public, public agencies, and owners of sites on the advantages of preserving, through continued or adaptive use, structures and equipment of significance in the history of technology, engineering, and industry. A membership information brochure and a sample copy of the Society's newsletter are available on request. Society for Industrial Archeology Room 5020 National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC 20560 • Copyright 1984 by Victor C. Darnell All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without permission, in writing. from the author or the Society for Industrial Archeology. Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 84-51536 • Cover illustration: 'The above illustration is taken direct from a photograph and shows a square end view of a Parabolic Truss Bridge designed and built by us at Williamsport, Pa. The bridge is built across the Susquehanna River and consists of five spans of 200 ft. each with a roadway 18 ft. wide in the clear. Since the bridge was built a walk has been added on the north side. This is one of the longest iron high way bridges in the State of Pennsylvania and is built after our Patent Parabolic Form.' The bridge was built in 1885 and had a short life, being destroyed by flood in the 1890s. -

Download This Article

he Boston and Worcester Railroad, span across the Quaboad one of the first railroads built in River at Warren, just west Massachusetts, was chartered in 1831 of Spencer. It was success- Historic and opened to Worcester in 1835. This ful, and they gave Howe Twas followed by the Western Railroad, which the contract to build a would begin in Worcester and run to the New much longer bridge at structures York State line, connecting with the Hudson and Springfield. Berkshire line that ran to Albany, New York, on Howe received a patent, significant structures of the past the Hudson River. The latter line was completed #1,711, on a bridge William Howe. in 1838. The Western Railroad reached the east- on August 3, 1840 while he was building the erly shore of the Connecticut River at Springfield Connecticut River Bridge. It had braces and coun- on October 1, 1839. The line of the Western ter braces crossing two panels, with additional Railroad from W. Springfield to the New York braces at the ends and additional longitudinal State over the lower Berkshire Mountains was member just below mid height. Long claimed completed on May 4, 1841. To make the con- that it was a violation of his patent rights, but nection across the Connecticut River required was unsuccessful in convincing the Patent Office ® a long bridge. Up to this time, most wooden they had erred in granting the patent to Howe. bridges were constructed to the design of Stephen Howe wrote, “The truss-frame which I am about H. Long and by Ethiel Town.