ENCLOSING FORESTS Towards Protection of Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onset of Southwest Monsoon – 2010

INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT (MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES) SOUTHWEST MONSOON-2013 END OF SEASON REPORT For the state of RAJASTHAN Compiled By Dr. O.P. Singh, Scientist-F S.S. Singh, Scientist-F R.N. Kumawat, S.A. Ashok Kumar Sharma, S.A. 1 HIGHLIGHTS For the country as a whole, the rainfall for the season (June-September) was 106% of its long period average (LPA). However, for North West India this figure came out to 129% and 127% for the state of Rajasthan. Seasonal rainfall was 127% of its LPA over East Rajasthan and 128% of its LPA over West Rajasthan. Southwest Monsoon current advanced over the Andaman Sea 3 days earlier than its normal date of 20th May and set in over Kerala on its normal date of 1st June. The southwest Monsoon set over South Eastern parts of the state on 13th June, about 2 days early. It progressed further very rapidly and covered the entire state by 16th June, about 1 month earlier than its normal date of 15th July. The withdrawal of Monsoon from west Rajasthan commenced on 9th September compared to its normal date of 1st September. After 19th, further withdrawal of southwest Monsoon was stalled for about one month with the successive formation of two low pressure areas and their westward movement across the central parts of the country. The Monsoon withdrew from the whole state on 17th October, 2013, delay of about 22 days from the LPA. Monthly rainfall over the state was 138% of LPA in June, 127% of LPA in July, 133% of LPA in August and 104% of LPA in September. -

Ground Water Scenario Baran District

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER SCENARIO BARAN DISTRICT WESTERN REGION JAIPUR 2013 GROUND WATER SCENARIO BARAN DISTRICT S. No. Item Information 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical area (sq. km) 6955.31 Administrative Divisions a. No. of tehsils / blocks 08/07 b. No. of villages 1114 inhabited 126 non habited c. No. of towns 4 d. No. of municipalities 4 Population (as per 2011 census) 1222755 Average annual rainfall (mm) (2001 - 707 2011) 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographical Units Hill ranges of Vindhyans in the northeast and low rounded hills of Malwa plateau in the south bound the region. Sedimentary rocks of Vindhyan Supergroup occupy northwestern part. Major Drainage The drainage system is well developed and represented by Chambal, which is perennial in nature. 3. LAND USE (ha) (2010-11) Forest area 216494 Net sown area 338497 Cultivable area (net sown area + 366348 fallow land) 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES 1. Deep black clayey soil 2. Deep brown loamy soil 3. Red gravelly loam hilly soil 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (ha) (2010-11) Food grains Bajra : 3472 Jowar : 2006 Wheat : 147930 Barley : 559 Rice : 8231 Maize : 16913 Total Pulses 10872 Total Oil seeds 311473 Total Condiments & Spices 67818 6. IRRIGATI ON BY DIFFERENT Net Area irrigated Gross area SOURCES (ha) irrigated Canal 54485 57488 S. No. Item Information Tank 2376 3137 Tubewells 191558 200258 Other wells 28252 28293 Other sources 16052 16820 Total 292723 306626 7. NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB No. of dug wells 20 No. of piezometers 1 8. PREDOMINENT GEOLOGICAL Upper Vindhyan, Bhander Group, FORMATIONS Ganurgarh shales, Bhander limestone and Bhander sandstone overlain by Deccan traps and alluvium of Quaternary age. -

THEIR OWN COUNTRY :A Profile of Labour Migration from Rajasthan

THEIR OWN COUNTRY A PROFILE OF LABOUR MIGRATION FROM RAJASTHAN This report is a collaborative effort of 10 civil society organisations of Rajasthan who are committed to solving the challenges facing the state's seasonal migrant workers through providing them services and advocating for their rights. This work is financially supported by the Tata Trust migratnt support programme of the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and Allied Trusts. Review and comments Photography Jyoti Patil Design and Graphics Mihika Mirchandani All communication concerning this publication may be addressed to Amrita Sharma Program Coordinator Centre for Migration and Labour Solutions, Aajeevika Bureau 2, Paneri Upvan, Street no. 3, Bedla road Udaipur 313004, Ph no. 0294 2454092 [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.aajeevika.org This document has been prepared with a generous financial support from Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and Allied Trusts In Appreciation and Hope It is with pride and pleasure that I dedicate this report to the immensely important, yet un-served, task of providing fair treatment, protection and opportunity to migrant workers from the state of Rajasthan. The entrepreneurial might of Rajasthani origin is celebrated everywhere. However, much less thought and attention is given to the state's largest current day “export” - its vast human capital that makes the economy move in India's urban, industrial and agrarian spaces. The purpose of this report is to bring back into focus the need to value this human capital through services, policies and regulation rather than leaving its drift to the imperfect devices of market forces. Policies for labour welfare in Rajasthan and indeed everywhere else in our country are wedged delicately between equity obligations and the imperatives of a globalised market place. -

{Ks=H; Fodkl Fohkkx }Kjk Vuql Wfpr {K

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES DR. Rajkumari Ahir MOHANLAL SUKHADIA UNIVERSITY, UDAIPUR Assistant Professor & PI No. Socio./UCSSH/2021-22/1265 Date: 12.07.2021 Advertisement for Research Associate, Research Assistant, Field Investigator, Computer Operator with accounts Assistant, GIS based Data Analyst and MTS worker Applications are invited from candidates on a plain paper for the post of Research Associate, Research Assistant, Field Investigator, Computer Operator with accounts Assistant, GIS based Data Analyst and MTS worker to work on the time-bound Research Project:ßtutkfr {ks=h; fodkl foHkkx }kjk vuqlwfpr {ks= eas lapkfyr fofHkUu 'kS{kf.kd] LokLF; ,oa vU; dY;k.kdkjh ;kstukvksa dk lgfj;k tutkfr ds thou ij iMus okys xq.kkRed izHkkoksa dk v/;;uß funded by The Center for Tribal Development (CTD), M.L.V. Research & Training Institute, Udaipur, Government of Rajasthan to Department of Sociolology, University College of Social science & Humanities, Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur (Rajasthan). Name of The Project ßtutkfr {ks=h; fodkl foHkkx }kjk vuqlwfpr {ks= eas lapkfyr fofHkUu 'kS{kf.kd] LokLF; ,oa vU; dY;k.kdkjh ;kstukvksa dk lgfj;k tutkfr ds thou ij iMus okys xq.kkRed izHkkoksa dk v/;;uß Funding Agency The Center for Tribal Development (CTD), M.L.V. Research & Training Institute, Udaipur, Government of Rajasthan Project Principal Dr. Rajkumari Ahir Investigator Assistant Professor Department of Sociolology, University College of Social science & Humanities, Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur (Rajasthan)-313001 Last date 18-07-2021 (1) Name of the Post Research Associate Tenure The position is temporary for 4 months or the position is coterminous with the project. -

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N

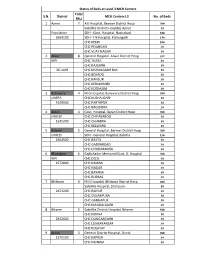

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 1 Ajmer 7 A K Hospital, Beawer District Hosp 300 Satellite District Hospital, Ajmer 30 Population SDH - Govt. Hospital, Nasirabad 100 2664100 SDH- Y N Hospital, Kishangarh 150 CHC KEKRI 100 CHC PISANGAN 30 CHC VIJAY NAGAR 30 2 Alwar 8 General Hospital, Alwar District Hosp 332 NIPI CHC TIJARA 30 CHC RAJGARH 50 36 LAKH CHC KISHANGARH BAS 50 CHC BEHROD 50 CHC BANSUR 30 CHC KERLIMANDI 30 CHC KOTKASIM 30 3 Banswara 4 M G Hospital, Banswara District Hosp 300 UNFPA CHC KUSHALGARH 50 1629900 CHC PARTAPUR 30 CHC BAGIDORA 30 4 Baran 4 Govt. Hospital, Baran District Hosp 300 UNICEF CHC CHIPABAROD 30 1245200 CHC CHHABRA 50 CHC KELWARA 30 5 Barmer 5 General Hospital, Barmer District Hosp 200 UNICEF SDH - General Hospital, Balotra 150 2404500 CHC BAYTU 30 CHC GADRAROAD 30 CHC DHORIMANNA 30 6 Bharatpur 6 RajBahadur Memorial Govt. D. Hospital 300 NIPI CHC DEEG 50 2572800 CHC KAMAN 30 CHC NAGAR 30 CHC BAYANA 50 CHC RUPBAS 30 7 Bhilwara 6 M G Hospital, Bhilwara District Hosp 400 Satellite Hospital, Shahpura 50 2453200 CHC RAIPUR 30 CHC GULABPURA 50 CHC GANGAPUR 50 CHC MANDALGARH 50 8 Bikaner 5 Satellite District Hospital, Bikaner 100 CHC NOKHA 50 2322600 CHC DUNGARGARH 30 CHC LUNKARANSAR 30 CHC KOLAYAT 30 9 Bundi 3 General District Hospital, Bundi 300 1170100 CHC KAPREN 30 CHC NAINWA 50 Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 10 Chittorgarh 5 District Hospital, Chittorgarh 300 1629900 CHC BEGUN 50 CHC KAPASAN 50 CHC BADISADRI 50 CHC NIMBAHERA 100 11 Churu 5 D B Hospital, Churu District Hospital 225 2059300 SDH - S R J Hospital, Ratangarh 100 SDH - S B Hospital, Sujangarh 100 CHC RAJGARH 50 CHC SARDARSHAHAR 75 12 Dausa 3 District Hospital, Dausa 150 NIPI CHC LALSOT 30 1606100 CHC MAHUWA 30 13 Dholpur 4 Sadar District Hospital, Dholpur 300 1196300 CHC RAJAKHERA 30 CHC BARI 50 CHC BASERI 30 14 Dungarpur 4 General District Hospital, Dungarpur 300 UNICEF SDH - Govt. -

List of Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Office Bearers-2017

List of Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Office bearers-2017 Chief Organiser 1 Shri Rakesh Pareek Shri Rakesh Pareek Chief Organiser Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal B-613 Sawai Jaisingh Highway, Vill/PO-Sarvad Ganeshganj Banipark Ajmer Jaipur Rajasthan Rajasthan Tel-09414419400 Mahila Organiser 1 Smt. Kalpana Bhatnagar Mahila Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal 46, Navrang Nagar Beawar, Dist- Ajmer Rajasthan Tel: 09001864018 Additional Chief OrganisersP 1 Shri Hajari Lal Nagar 2 Shri Ram Kishan Sharma Additional Chief Organiser Additional Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal C 4/272 Vidyadhar Nagar Ghanshyam Ji Ka Mandir Jaipur (Rajasthan) Gangapol Bahar, Badanpura Tel:- 09214046342, 09414446342 Jaipur 09829783637 Rajasthan Tel:- 09314504631 3 Shri Hulas Chand Bhutara 4 Shri Manjoor Ahmed Additional Chief Organiser Additional Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal C-53, Panchshel Colony 4354, Mohalla Kayamkhani Purani Chungi Topkhano Ka Rasta Ajmer Road Chandpol Bazar Jaipur--302019 Jaipur Rajasthan Rajasthan Tel: 01531-220642, 09414147159 Tel: 09314603489, 08890473767 09079004827 5 Shri Bhawani Mal Ajmera 6 Shri Ram Bharosi Saini Additional Chief Organiser Additional Chief Organiser Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rajasthan Pradesh Congress Seva Dal Rahul Electricals, V/Post- Chantali Ganesh Shopping Teh- Wair Complex, Opp.R No-2, Dist- Bharatpur VKI Chonu Rd. Rajasthan -

Food Intake of Tribes in Rajasthan: a Review TPI 2019; 8(6): 753-756 © 2019 TPI Darshika Joshi and Dr

The Pharma Innovation Journal 2019; 8(6): 753-756 ISSN (E): 2277- 7695 ISSN (P): 2349-8242 NAAS Rating: 5.03 Food intake of tribes in Rajasthan: A review TPI 2019; 8(6): 753-756 © 2019 TPI www.thepharmajournal.com Darshika Joshi and Dr. Pramod K Raghav Received: 22-04-2019 Accepted: 24-05-2019 Abstract Darshika Joshi Tribes are still shrouded in mystery. Almost half of the world’s tribal population reside in India. The Research Scholar, Department of highest concentration of tribal population is mainly in districts like: Udaipur, Bhilwara, Dungerpur, Food and Biotechnology, Banswara, Chittorgarh, Pratapgarh, and Rajsamanin Rajasthan. The tribal populations are ‘at risk’ of Faculty of Agriculture & under dietary practices due to their over-reliance on primitive agricultural practices and uncertainty of Veterinary Science, Jayoti food supply. Regarding nutrient intake of tribes was energy calcium, iron, β-carotene and folate were Vidyapeeth Women’s University, found grossly inadequate in tribes in Rajasthan. Bhils showed the lowest BMI compared to other tribes. Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Dr. Pramod K Raghav Keywords: Bhil, food intake, garasia, nutritional status, Rajasthan, tribe Professor, Department of Food and Biotechnology, Faculty of Introduction Agriculture & Veterinary India is a land of many cultures and people. Tribe is origenated from the Latin word ‘tribes’ Science, Jayoti Vidyapeeth meaning the ‘poor among masses’. With more than 84.4 million, India has the largest Women’s University, Jaipur, [4] Rajasthan, India population of the tribal people in the world (Das and Bose, 2012) . The tribes of India comprise about 8% of the total population of the country having probably the largest number of tribal communities in the world (Topal and Samal, 2001) [26]. -

Rajpushtika July 2021 Eng

J U L Y 2 0 2 1 | I S S U E 5 In This Issue Read about our study on Infant & Young Child Feeding practices in Rajasthan Learn about teenage pregnancy and how to manage risks Revealed: The answers to our nutrition quiz In the Learning from the Community news Community members in Banswara we talked to for our qualitative study “He only eats tanatan (a packaged Patriarchal expectations remain rife. Article on local foods of Rajasthan While most people gave lip service to published in Rajasthan Patrika. snack) and biscuits,” says Lali Bai*, a RajPusht promotes local, seasonal young mother in Digodpaar, Baran the fact that girls and boys are equal, foods to ensure dietary diversity and 1 CORINfoToHd sIeAcuNritSy. 15:58 District. Her 7-month old son refuses their expressions suggested otherwise. to have home-cooked food. But he is not the only one. Many parents A mother of two daughters teared up initiate complementary feeding of after a perfunctory answer to a infants with junk foods. Cheap, question about gender equality and convenient and easily available, they following a heavy silence, said that are the go-to for some mothers if her mother-in-law didn’t want their child does not take to another girl. Such is the desire for a boy among families that according to Sunil Kumar, Deputy Team Leader, homemade foods after six months of RajPusht, shared insights on childhood Rama, a staff nurse in one of the diarrhoea management and Poshan exclusive breastfeeding. Abhiyaan with the Health Department, districts, many mothers refuse to Bhilwara District, in a webinar on July 14. -

CGST Udaipur

Scanned by CamScanner ANNEXURE -A LIST OF GST DIVISIONS & RANGES COMMISSIONERATE NAME: UDAIPUR COMMISSIONERATE CODE: WP Division Code Division Name Division Jurisdiction Division Address WP01 GST Division-A, Udaipur Area of Girwa tehsil Left side from Baleecha By-Pass via Goverdhan Vilas, Railway Station upto Surajpole of 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Udaipurcity and Area from left side of Suraj pole to Dabok of Tehsil Girwa. Jhadol, Kotda, Badgaon, Gogunda and Mavli tehsil of Udaipur Distt. Range Code Range Name Range Jurisdiction Range Address WP0101 GST Range-I Left side of Surajpole to starting point of NH-27 (Opp.Pacific Dental College, Debari) via Sevashram, Pratap Nagar 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Choraha of Girwa Tehil upto Amberi Pulia to Surajpole via Sukhadia Circle, Chetak Circle and entrire area of Kotda Tehsil and remaing part of Badgaon Tehsil other then mention in Range IV of Udaipur Distt. WP0102 GST Range-II Right side of part of Girwa Tehil starting from Dabok on NH 76 to Amberi Pulia via starting point of NH27 and 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Amberi Pulia Nathdwara Road (part of Girwa Tehsil) and entire area of Gogunda Tehsil of Udaipur Distt. WP0103 GST Range-III Left side of NH48 from Baleecha By-Pass via Goverdhan Vilas, Railway Station upto Fatehpura circle via Court 142 B, Sector 11, Hiran Magri, Udaipur 313001 Choraha and from Fatehpura circle to Rampura Circle via Devali, Rani Road, Mahakaleshwar Mandir, Mullatali (Subash Choraha) and from Ram Pura Circle to Nai and back to Baleecha via Sisarma. -

A Case of Sadar Block in Pratapgarh District of Uttar

Research Article Int J Environ Sci Nat Res Volume 10 Issue 4 - April 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ashutosh Mishra DOI: 10.19080/IJESNR.2018.10.555791 Analysis of Temperature and Rainfall Patterns of Rajasthan Ashutosh Mishra* Senior Research Fellow, Geography Department, University of Allahabad, India Submission: April 04, 2018; Published: April 27, 2018 *Corresponding author: Ashutosh Mishra, Senior Research Fellow, Geography Department, University of Allahabad, India, Tel: Email: Abstract aggravatePresent its paperclimatic examines harshness, the andtemperature thus, can andadversely rainfall impact profile the of physical,Rajasthan. as This well largestas economic Indian land state scapes. is known The foranalysis extreme reveals temperatures, that most water scarcity, scanty rains and frequent droughts. It is feared that any significant change in temperature and rainfall properties of the state can recorded a cooling trend. Interestingly, the warming is more prominent in the western part of the state as compared to its eastern part. As for asof therainfall districts is concerned, in the state it has have recorded witnessed an increase a significant for most warming of districts, during however, last century. the districtsThe districts lying ofnear Sikar Tropic and ofDausa, Cancer on have the other become hand, drier. have Keywords: Climate change; desertification; ARIMA model; Regression; F value Introduction the state are namely the western desert, the Aravali hills, eastern Climate is the most vital element of the nature. It shapes both plain and south-east plateau region. The great Thar desert, the physical as well as biological kingdoms. Human evolution, which is expanded over 58 percent land of the state, and is also in itself, is an outcome of changing climatic scenes. -

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Economic Sector for the Year Ended 31 March 2017

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Economic Sector for the year ended 31 March 2017 Government of Rajasthan Report No. 5 of the year 2017 Presented to the Legislature on 27 FEB 2018. Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Economic Sector for the year ended 31 March 2017 Government of Rajasthan Report No. 5 of the year 2017 http://www.cag.gov.in Table of Contents Reference to Paragraph Page Preface - (v) Chapter I Introduction About this Report 1.1 1 Profile of Audited Entities 1.2 1 Authority for Audit 1.3 2 Organisational Structure of the Office of the Accountant General (Economic and Revenue Sector Audit), 1.4 2 Rajasthan Planning and conduct of audit 1.5 3 Significant audit observations 1.6 3 Response of the Departments to Performance Audit/Compliance Audit Paragraphs 1.7 9 Follow-up on Audit Reports 1.8 9 Chapter II Performance Audit Environment Department Role of Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board in controlling air pollution in the State 2.1 11 Chapter III Compliance Audit Mines, Geology and Petroleum Department Adherence to Environmental Issues on Mining Activities in Rajasthan 3.1 49 Forest Department Development of water catchment through greening of Rajasthan 3.2 73 Public Works Department Implementation of Rajasthan Road Sector Modernization Project 3.3 80 Non-completion of road led to non-connectivity of habitations 3.4 88 (i) Audit Report (Economic Sector) for the year ended 31 March 2017 Reference to Paragraph Page Public Works Department Irregular payment to contractors for -

Brief Industrial Profile of Baran District

lR;eso t;rs Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Baran District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) 22 Godam, Industrial Estate, Jaipur-302006 Phone: 0141-2212098, 2213099 Fax: 0141-2210553 E-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmedijaipur.gov.in 1 2 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 4 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 4 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 4 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 2. District at a glance 5-7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area 7 3. Industrial Scenario 3.1 Industry at a Glance 7 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 8 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 8 3.5 Major Exportable Item 8 3.6 Growth Trend 9 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 9 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 9 3.8.1 List of the units 9 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 9 3.9 Service Enterprises 9 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 9 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 9 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 10 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 10 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 10 4.1.2 Service Sector 10 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 10 4.2.1 Handloom Cluster 10 4.2.2 Leather Juti cluster 11 4.2.3 Dona Pattal cluster 11 4.2.4 Wooden Toys Cluster 12 4.2.