Strict Tort Liability of Manufacturers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 2:12-Cv-01114-JD Document 17 Filed 10/19/12 Page 1 of 9

Case 2:12-cv-01114-JD Document 17 Filed 10/19/12 Page 1 of 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA _____________________________________ DAVID S. TATUM, : CIVIL ACTION : NO. 12-1114 : Plaintiff, : v. : : TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS : NORTH AMERICA, INC., TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS AMERICA, INC., : TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS : INTERNATIONAL, INC., TAKEDA : PHARMACEUTICALS COMPANY : LIMITED, TAKEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, LLC, TAKEDA : AMERICA HOLDINGS, INC., TAKEDA : GLOBAL RESEARCH & : DEVELOPMENT CENTER, INC., : TAKEDA SAN DIEGO, INC., TAP : PHARMACEUTICALS PRODUCTS, INC., ABBOTT LABORATORIES, INC., : DOES 1 THROUGH 100 INCLUSIVE, : : Defendants. : _____________________________________ DuBois, J. October 18, 2012 M E M O R A N D U M I. INTRODUCTION This is a product liability action in which plaintiff David S. Tatum alleges that the PREVACID designed, manufactured, and marketed by defendants weakened his bones, ultimately leading to hip fractures. The defendants filed a motion to dismiss many of the claims in Tatum’s First Amended Complaint. For the reasons that follow, the Court grants in part and denies in part defendants’ motion. II. BACKGROUND1 Tatum was prescribed PREVACID, a pharmaceutical drug designed, manufactured, and 1 As required on a motion to dismiss, the Court takes all plausible factual allegations contained in plaintiff’s First Amended Complaint to be true. Case 2:12-cv-01114-JD Document 17 Filed 10/19/12 Page 2 of 9 marketed by defendants. (Am. Compl. 3, 7.) After taking PREVACID, Tatum began feeling pain in his left hip, and he was later diagnosed with Stage III Avascular Necrosis. (Id. at 7.) Tatum’s bones became weakened or brittle, causing multiple fractures. -

July 25, 2019 NACDL OPPOSES AFFIRMATVE CONSENT

July 25, 2019 NACDL OPPOSES AFFIRMATVE CONSENT RESOLUTION ABA RESOLUTION 114 NACDL opposes ABA Resolution 114. Resolution 114 urges legislatures to adopt affirmative consent requirements that re-define consent as: the assent of a person who is competent to give consent to engage in a specific act of sexual penetration, oral sex, or sexual contact, to provide that consent is expressed by words or action in the context of all the circumstances . The word “assent” generally refers to an express agreement. In addition the resolution dictates that consent must be “expressed by words or actions.” The resolution calls for a new definition of consent in sexual assault cases that would require expressed affirmative consent to every sexual act during the course of a sexual encounter. 1. Burden-Shifting in Violation of Due Process and Presumption of Innocence: NACDL opposes ABA Resolution 114 because it shifts the burden of proof by requiring an accused person to prove affirmative consent to each sexual act rather than requiring the prosecution to prove lack of consent. The resolution assumes guilt in the absence of any evidence regarding consent. This radical change in the law would violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and the Presumption of Innocence. It offends fundamental and well-established notions of justice. Specifically, Resolution 114 urges legislatures to re-define consent as “the assent of a person who is competent to give consent to engage in a specific act of sexual penetration, oral sex, or sexual contact, to provide that consent is expressed by words or action in the context of all the circumstances . -

The Constitutionality of Strict Liability in Sex Offender Registration Laws

THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF STRICT LIABILITY IN SEX OFFENDER REGISTRATION LAWS ∗ CATHERINE L. CARPENTER INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 296 I. STATUTORY RAPE ............................................................................... 309 A. The Basics.................................................................................... 309 B. But the Victim Lied and Why it Is Irrelevant: Examining Strict Liability in Statutory Rape........................................................... 315 C. The Impact of Lawrence v. Texas on Strict Liability................... 321 II. A PRIMER ON SEX OFFENDER REGISTRATION LAWS AND THE STRICT LIABILITY OFFENDER.............................................................. 324 A. A Historical Perspective.............................................................. 324 B. Classification Schemes ................................................................ 328 C. Registration Requirements .......................................................... 331 D. Community Notification Under Megan’s Law............................. 336 III. CHALLENGING THE INCLUSION OF STRICT LIABILITY STATUTORY RAPE IN SEX OFFENDER REGISTRATION.............................................. 338 A. General Principles of Constitutionality Affecting Sex Offender Registration Laws........................................................................ 323 1. The Mendoza-Martinez Factors............................................. 338 2. Regulation or -

Torts - Trespass to Land - Liability for Consequential Injuries Charley J

Louisiana Law Review Volume 21 | Number 4 June 1961 Torts - Trespass To land - Liability for Consequential Injuries Charley J. S. Schrader Jr. Repository Citation Charley J. S. Schrader Jr., Torts - Trespass To land - Liability for Consequential Injuries, 21 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol21/iss4/23 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 862 LOUISIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol. XXI is nonetheless held liable for the results of his negligence. 18 It would seem that this general rule that the defendant takes his victim as he finds him would be equally applicable in the instant type of case. The general rule, also relied upon to some extent by the court in the instant case, that a defendant is not liable for physical injury resulting from a plaintiff's fear for a third person, has had its usual application in situations where the plaintiff is not within the zone of danger.' 9 Seemingly, the reason for this rule is to enable the courts to deal with case where difficulties of proof militate against establishing the possibility of recovery. It would seem, however, that in a situation where the plaintiff is within the zone of danger and consequently could recover if he feared for himself, the mere fact that he feared for another should not preclude recovery. -

A Law and Norms Critique of the Constitutional Law of Defamation

PASSAPORTISBOOK 10/21/2004 7:39 PM NOTE A LAW AND NORMS CRITIQUE OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF DEFAMATION Michael Passaportis* INTRODUCTION................................................................................. 1986 I. COLLECTIVE ACTION PROBLEMS AND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY....................................................................................... 1988 II. BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS AND NORMS .................................. 1990 III. ESTEEM, GOSSIP, AND FALSE GOSSIP ...................................... 1994 A. The Negative Externality of False Gossip ......................... 1995 B. Punishment of False Negative Gossip ............................... 2001 IV. THE LAW OF DEFAMATION AND ITS CONSTITUTIONALIZATION ........................................................ 2004 A. Defamation at Common Law............................................. 2005 B. The Constitutional Law of Defamation............................. 2008 V. THE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF DEFAMATION AND NORMS . 2013 A. The Problem of Under-Produced Political Speech.......... 2013 B. The Actual Malice Rule and Normative Behavior ........... 2019 VI. THE COMMON LAW VERSUS SULLIVAN FROM A LAW AND ECONOMICS PERSPECTIVE......................................................... 2022 A. The Economics of Strict Liability ...................................... 2022 B. Strict Liability and Defamation.......................................... 2027 C. Was the Common Law of Defamation Efficient? ............ 2032 CONCLUSION.................................................................................... -

Is There Really No Liability Without Fault?: a Critique of Goldberg & Zipursky

IS THERE REALLY NO LIABILITY WITHOUT FAULT?: A CRITIQUE OF GOLDBERG & ZIPURSKY Gregory C. Keating* INTRODUCTION In their influential writings over the past twenty years and most recently in their article “The Strict Liability in Fault and the Fault in Strict Liability,” Professors Goldberg and Zipursky embrace the thesis that torts are conduct-based wrongs.1 A conduct-based wrong is one where an agent violates the right of another by failing to conform her conduct to the standard required by the law.2 As a description of negligence liability, the characterization of torts as conduct-based wrongs is both correct and illuminating. Negligence involves a failure to conduct oneself as a reasonable person would. It is fault in the deed, not fault in the doer. At least since Vaughan v. Menlove,3 it has been clear that a blameless injurer can conduct himself negligently and so be held liable.4 Someone who fails to conform to the standard of conduct expected of the average reasonable person and physically harms someone else through such failure is prima * William T. Dalessi Professor of Law and Philosophy, USC Gould School of Law. I am grateful to John Goldberg and Ben Zipursky both for providing a stimulating paper and for feedback on this Article. Daniel Gherardi provided valuable research assistance. 1. John C.P. Goldberg & Benjamin C. Zipursky, The Strict Liability in Fault and the Fault in Strict Liability, 85 FORDHAM L. REV. 743, 745 (2016) (“[F]ault-based liability is . liability predicated on some sort of wrongdoing. [L]iability rests on the defendant having been ‘at fault,’ i.e., having failed to act as required.”). -

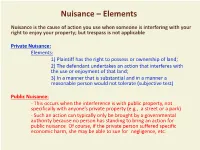

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability

Michigan Law Review Volume 64 Issue 7 1966 Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability John A. Sebert Jr. University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John A. Sebert Jr., Products Liability--The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability, 64 MICH. L. REV. 1350 (1966). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol64/iss7/10 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS Products Liability-The Expansion of Fraud, Negligence, and Strict Tort Liability The advances in recent years in the field of products liability have probably outshone, in both number a~d significance, the prog ress during the same period in most other areas of the law. These rapid developments in the law of consumer protection have been marked by a consistent tendency to expand the liability· of manu facturers, retailers, and other members of the distributive chain for physical and economic harm caused by defective merchandise made available to the public. Some of the most notable progress has been made in the law of tort liability. A number of courts have adopted the principle that a manufacturer, retailer, or other seller1 of goods is answerable in tort to any user of his product who suffers injuries attributable to a defect in the merchandise, despite the seller's exer cise of reasonable care in dealing with the product and irrespective of the fact that no contractual relationship has ever existed between the seller and the victim.2 This doctrine of strict tort liability, orig inally enunciated by the California Supreme Court in Greenman v. -

Comparative Negligence and Strict Tort Liability Marcus L

Louisiana Law Review Volume 40 | Number 2 Symposium: Comparative Negligence in Louisiana Winter 1980 Comparative Negligence and Strict Tort Liability Marcus L. Plant Repository Citation Marcus L. Plant, Comparative Negligence and Strict Tort Liability, 40 La. L. Rev. (1980) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol40/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE NEGLIGENCE AND STRICT TORT LIABILITY Marcus L. Plant* Strict liability1 in tort occupies a prominent place in Louisiana jurisprudence. Chief Judge Hunter of the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana has recently written: "The Louisiana Civil Code is replete with instances of liability based on breach of duty where there is neither negligence nor intentional misconduct by the party liable."2 Such liability has been applied in cases in which defendant has engaged in blasting,3 crop spraying,4 and pile driving.' In a 1971 case, the defendant, having stored poisonous gas, conceded initial liability for the escape of the gas despite the absence of any negligence on its part.' In that same year the Louisiana Supreme Court adopted a strict tort liability approach with respect to manufacturers of defective products Recently, there has been further expansion of the areas of human conduct that are to be governed by the principles of strict tort liability. In 1974 article 2321 of the Louisiana Civil Code, relating to the liability of the owner of an animal, was construed to impose liability on the owner "in the nature of strict liability."8 In 1975 there were similar interpretations of article 2318, relating to parents' liability for *Professor of Law, University of Michigan. -

Duty in Tort Law: an Economic Approach

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 3 Article 16 2006 Duty in Tort Law: An Economic Approach Keith N. Hylton Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Keith N. Hylton, Duty in Tort Law: An Economic Approach, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 1501 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss3/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Duty in Tort Law: An Economic Approach Cover Page Footnote Professor of Law, Boston University, [email protected]. This paper was presented at the Fordham Law School's Symposium The Internal Point of View in Law and Ethics. For helpful comments I thank Youngjae Lee, Benjamin Zipursky, Katrina Wyman, and other conference participants. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss3/16 DUTY IN TORT LAW: AN ECONOMIC APPROACH Keith N. Hylton* INTRODUCTION Torts textbooks say that a negligence claim consists of four components: duty, breach, causation, and damages. The plaintiff must show, or at least the court must be prepared to assume, that the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty to take care. If the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care, the plaintiff will be permitted to prove that the defendant breached the duty of care. -

Strict Liability A. Strict Liability for Trespassory Torts and the Advent of Fault Theory 1. Strict Liability Under Trespass At

Strict Liability A. Strict Liability for Trespassory Torts and the Advent of Fault Theory 1. Strict Liability Under Trespass at Early Common Law. Text 2. Strict Liability Applied and Signs of Change to Come. Weaver 3. Change Arrives: Fault Theory Adopted. Brown B. Strict Liability After Brown v. Kendall 1. Trespassing Animals and Dangerous Animals. RST 3d 2. Non-Natural Uses. Rylands 3. Abnormally Dangerous Activities. RST 3d Restatement (Third) on Torts: Liability for Physical Harm § 20. Abnormally Dangerous Activities (a) An actor who carries on an abnormally dangerous activity is subJect to strict liability for physical harm resulting from the activity. (b) An activity is abnormally dangerous if: (1) the activity creates a foreseeable and highly significant risk of physical harm even when reasonable care is exercised by all actors; and (2) the activity is not one of common usage. Hypothetical 1 At the end of the planting season, farmer Fred needs to dispose of dry straw spread over much of his 50 acres. He therefore initiates a controlled burn fire, with the aim of using the fire to destroy the straw. For fires of this sort there are appropriate precautions, including placing various types of obstacles at the property’s boundary line. However, even when all reasonable precautions are adopted, such fires escape the farmer’s property approximately 10 percent of the time. Because of the size of such fires, when there is such an escape, the damage done to neighboring property is liKely to be substantial. When Fred’s fire is in progress, the wind unexpectedly picKs up. -

The Morality of Strict Tort Liability

William & Mary Law Review Volume 18 (1976-1977) Issue 2 Symposium: Philosophy of Law Article 3 December 1976 The Morality of Strict Tort Liability Jules L. Coleman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Repository Citation Jules L. Coleman, The Morality of Strict Tort Liability, 18 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 259 (1976), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol18/iss2/3 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr THE MORALITY OF STRICT TORT LIABILITY JULES L. COLEMAN* Accidents occur; personal property is damaged and sometimes is lost altogether. Accident victims are likely to suffer anything from mere bruises and headaches to temporary or permanent disability to death. The personal and social costs of accidents are staggering. Yet the question of who should bear these costs has turned the heads of few philosophers and has occasioned surprisingly little philo- sophic discussion. Perhaps that is because the answer has seemed so obvious; accident costs, at least the nontrivial ones, ought to be borne by those at fault in causing them.' The requirement of fault at one time appeared to be so deeply rooted in the concept of per- sonal responsibility that in the famous Ives2 case, Judge Werner was moved to argue that liability without fault was not only immoral, but also an unconstitutional violation of due process of law. Al- * Ph.D., The Rockefeller University; M.S.L., Yale Law School. Associate Professor of Philosophy, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.