African Ethnonyms and Toponyms: an Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language and Identity

THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF GEOLINGUISTICS LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY SELECTED PAPERS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OCTOBER 2-5, 2002 SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF GEOLINGUISTICS BARUCH COLLEGE (CUNY) Edited by Leonard R. N. Ashley (Brooklyn College, CUNY, Emeritus) and Wayne H. Finke jBanach College, CUNY) CUMMINGS + HATHAWAY -j /4 408 409 Works Cited I CURRENT ETHNOLJNGUISTIC CONCERNS AMONG September 2,2001, AS. Gevin, a.’The Secret Life of Plants,” New York Times THE OVERLOOKED THANGMI OF NEPAL Opera Playbill April 2002, 3946. Innaurat, Albert. “Program Notes Madame Butterfly,” Metropolita.n Mark Turin Digital Himalaya Project Cite Language Barriers, Wall Street JournaI May 23 Kulish, Michael & Kelly Spors. “Voting Suits to Depment of Social Anthropology 2002. University of Cambridge Opera News May 2002, 12. Peters, Brooks. “Miss Italy,” and Plants,” Discover April 2002, 47—51. Russell, S. A. “Talking Department of Anthropology Safire, William, “On Language,” San Juan Star February 17, 2002, 34. Cornell University 2002, 142—148. Thomas, Mario. “Right Words, Right Time...,” Readers Digest June Introduction New York Times April 18, 2002. Wines, Michael. “Russia Resists Plans to Tweak the Mother Tongue,” In the 1992 Banquet Address to the American Society of Geolinguistics, Roland J. L. Breton spoke of four levels of linguistic development. The first level, in his view, was made up of “the native, ethnic, vernacular mother tongues and home languages, which by a large majority are still restricted to oral use without any written text, dictionary, grammar or teaching...” (Breton 1993: 4-5). Breton’s description is an accurate portrayal of Thangmi, a little-known Tibeto-Burman language spoken by an ethnic group of the same name in the valleys of eastern Nepal, and the subject of this article. -

Brief Guide to the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry

1 Brief Guide to the Nomenclature of Table 1: Components of the substitutive name Organic Chemistry (4S,5E)-4,6-dichlorohept-5-en-2-one for K.-H. Hellwich (Germany), R. M. Hartshorn (New Zealand), CH3 Cl O A. Yerin (Russia), T. Damhus (Denmark), A. T. Hutton (South 4 2 Africa). E-mail: [email protected] Sponsoring body: Cl 6 CH 5 3 IUPAC Division of Chemical Nomenclature and Structure suffix for principal hept(a) parent (heptane) one Representation. characteristic group en(e) unsaturation ending chloro substituent prefix 1 INTRODUCTION di multiplicative prefix S E stereodescriptors CHEMISTRY The universal adoption of an agreed nomenclature is a key tool for 2 4 5 6 locants ( ) enclosing marks efficient communication in the chemical sciences, in industry and Multiplicative prefixes (Table 2) are used when more than one for regulations associated with import/export or health and safety. fragment of a particular kind is present in a structure. Which kind of REPRESENTATION The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) multiplicative prefix is used depends on the complexity of the provides recommendations on many aspects of nomenclature.1 The APPLIED corresponding fragment – e.g. trichloro, but tris(chloromethyl). basics of organic nomenclature are summarized here, and there are companion documents on the nomenclature of inorganic2 and Table 2: Multiplicative prefixes for simple/complicated entities polymer3 chemistry, with hyperlinks to original documents. An No. Simple Complicated No. Simple Complicated AND overall -

Minutes of the IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (VIII) Committee Meeting Boston, MA, USA, August 18, 2002

Minutes of the IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (VIII) Committee Meeting Boston, MA, USA, August 18, 2002 Members Present: Dr Stephen Heller, Prof Herbert Kaesz, Prof Dr Alexander Lawson, Prof G. Jeffrey Leigh, Dr Alan McNaught (President), Dr. Gerard Moss, Prof Bruce Novak, Dr Warren Powell (Secretary), Dr William Town, Dr Antony Williams Members Absent: Dr. Michael Dennis, Prof Michael Hess National representatives Present: Prof Roberto de Barros Faria (Brazil) The second meeting of the Division Committee of the IUPAC Division of Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation held in the Great Republic Room of the Westin Hotel in Boston, Massachusetts, USA was convened by President Alan McNaught at 9:00 a.m. on Sunday, August 18, 2002. 1.0 President McNaught welcomed the members to this meeting in Boston and offered a special welcome to the National Representative from Brazil, Prof Roberto de Barros Faria. He also noted that Dr Michael Dennis and Prof Michael Hess were unable to be with us. Each of the attendees introduced himself and provided a brief bit of background information. Housekeeping details regarding breaks and lunch were announced and an invitation to a reception from the U. S. National Committee for IUPAC on Tuesday, August 20 was noted. 2.0 The agenda as circulated was approved with the addition of a report from Dr Moss on the activity on his website. 3.0 The minutes of the Division Committee Meeting in Cambridge, UK, January 25, 2002 as posted on the Webboard (http://www.rsc.org/IUPAC8/attachments/MinutesDivCommJan2002.rtf and http://www.rsc.org/IUPAC8/attachments/MinutesDivCommJan2002.pdf) were approved with the following corrections: 3.1 The name Dr Gerard Moss should be added to the members present listing. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ethnicity, Essentialism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ethnicity, Essentialism, and Folk Sociology among the Wichí of Northern Argentina A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Anthropology by Alejandro Suleman Erut 2017 © Copyright by Alejandro Suleman Erut 2017 ! ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Ethnicity, essentialism, and folk sociology among the Wichí of Northern Argentina by Alejandro Suleman Erut Master of Arts in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Harold Clark Barrett, Chair This work explores the cognitive bases of ethnic adscriptions in the cultural context of a Native American group of Northern Argentina, namely: the Wichí. In the first part, previous hypotheses that attempted to explain the evolved mechanisms involved in ethnic induction and categorization are discussed. In this regard, the explanatory power of folk biology vs. folk sociology is intensively discussed when confronted with the results obtained in the field. The results of the first study suggest that the Wichí do not use biological information, and do not make ontological commitments based on it when ascribing ethnic identity. The second part is devoted to presenting psychological essentialism as a series of heuristics that can be instantiated independently for different cognitive domains. In this sense, the proposal advocates for a disaggregation of the heuristics associated with psychological essentialism, and for the implementation of an approach that explores each heuristic separately as a consequence of the cultural, ecological, and perhaps historical context of instantiation. The results of study two suggest that a minimal trace of essentialism is underlying Wichí ethnic conceptual structure. However, this trace is not related to heuristics that receive biological information as an input; on the contrary, it seems that the ascription of ethnic identity relates to the process of socialization. -

Types of Ethnonyms According to Level Motivation of Nomination

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 12, 2020 TYPES OF ETHNONYMS ACCORDING TO LEVEL MOTIVATION OF NOMINATION 1Atajonova Anorgul Jumaniyazovna 1Candidate of Philological Sciences, Docent, Urgench State University, Urgench, Uzbekistan. E-mail address: [email protected] Received: 05.03.2020 Revised: 07.04.2020 Accepted: 09.05.2020 Abstract The study and scientific generalization of the lexical properties of ethnonyms and ethno-toponyms using linguistic and non-linguistic factors is an urgent problem of modern Uzbek onomastics. Because ethnonyms and ethno-names in the Uzbek language, on the one hand, are considered modern (synchronous) material, on the other hand, they are the most ancient, i.e. original names. Therefore, it is impossible to carry out their research using only one method. Based on this, it is advisable to use descriptive, historical-comparative, and historical-etymological methods in toponymic studies. We believe that the phenomenon of the origin of ethnonyms based on the names of the emblems first appeared among cattle-breeding ethnic groups. The names of marks serving as a sign of distinguishing livestock from each other, due to the expansion of meaning, turned into an ethnic term. Some marks of stigma also came from totems. Keywords: ethnonyms, Ancient Khorezm, folklore, spiritual treasury, historical origin, residence. © 2020 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.12.45 INTRODUCTION Beautiful Soul”) by Mahmoud ibn Kushmukhammad Khivaki The names of places are a kind of encyclopedia on the history, (19th century), also in the historical and geographical treatises of fate and lifestyle of our people, an invaluable monument of folk Istahri, Hamdulloh Mustafi Qazvini, Amin Amad Razi a range wisdom, a great value, enriching the spiritual treasury of our number of ethnonyms and ethno-names in Khorezm are people for centuries. -

The 'Big Bang' of Dravidian Kinship Ruth Manimekalai

:<5:1$:J$;Q``:01R1:[email protected]] THE ‘BIG BANG’ OF DRAVIDIAN KINSHIP RUTH MANIMEKALAI VAZ Introduction This article is about the essential nature of transformations in Dravidian kinship systems as may be observed through a comparison of a few contemporary ethnographic examples. It is a sequel 1 to an earlier article entitled ‘The Hill Madia of central India: early human kinship?’ (Vaz 2010), in which I have described the structure of the Madia kinship system as based on a rule of patrilateral cross-cousin (FZD) marriage. I concluded that article by saying that a complex bonding of relations, rather than a simple structure, seems to be the essential feature of the Proto- Dravidian kinship terminology and that it is only from the point of view of such an original state that Allen’s (1986) ‘Big Bang’ model for the evolution of human kinship would make sense. The aim of the present article is first, to discuss certain aspects of the transformations of Dravidian kinship, and secondly, to reconsider Allen’s ‘Big Bang’ model. I begin with a review of some theoretical perspectives on Proto-Dravidian as well as on proto-human kinship and a brief reference to the role of marriage rules in human kinship systems. This is followed by the main content of this article, which is a comparative analysis of three Dravidian kinship systems (actually, two Dravidian and one Dravidianized) and an Indo-Aryan system, on the basis of which I have proposed a revised ‘Big Bang’ model. Why the ‘Big Bang’ analogy for Dravidian kinship? Trautmann has used the analogy of a tree trunk and its branches for proto-Dravidian kinship, while stating that the ‘trunk’ does not exist anymore (Trautmann 1981: 229). -

Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler a Dissertati

Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Chair Ann Anagnost Stevan Harrell Danny Hoffman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology ©Copyright 2018 Darren T. Byler University of Washington Abstract Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies This study argues that Uyghurs, a Turkic-Muslim group in contemporary Northwest China, and the city of Ürümchi have become the object of what the study names “terror capitalism.” This argument is supported by evidence of both the way state-directed economic investment and security infrastructures (pass-book systems, webs of technological surveillance, urban cleansing processes and mass internment camps) have shaped self-representation among Uyghur migrants and Han settlers in the city. It analyzes these human engineering and urban planning projects and the way their effects are contested in new media, film, television, photography and literature. It finds that this form of capitalist production utilizes the discourse of terror to justify state investment in a wide array of policing and social engineering systems that employs millions of state security workers. The project also presents a theoretical model for understanding how Uyghurs use cultural production to both build and refuse the development of this new economic formation and accompanying forms of gendered, ethno-racial violence. -

Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia Michel Ferlus

Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia Michel Ferlus To cite this version: Michel Ferlus. Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia. 42nd International Conference on Sino- Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Payap University, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. halshs- 01182596 HAL Id: halshs-01182596 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01182596 Submitted on 1 Aug 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics Payap University, Chiang Mai, November 2-4, 2009 Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia Michel Ferlus Independent researcher (retired from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France) In the Southeast Asian Sinosphere, we can observe a circulation of ethnonyms between local languages and Chinese. A local Southeast Asian autonym is borrowed into Chinese, undergoes sound changes affecting the Chinese language, and then returns to the original populations, or to other populations. The result is a coexistence of ethnonyms of highly different phonetic outlook but originating in the same etymon. We will examine four families of ethnonyms, mostly Austroasiatic and Tai-Kadai. Some of these ethnonyms are still in use today, others are known through Chinese texts where they are transcribed by phonograms. -

SEM 63 Annual Meeting

SEM 63rd Annual Meeting Society for Ethnomusicology 63rd Annual Meeting, 2018 Individual Presentation Abstracts SEM 2018 Abstracts Book – Note to Reader The SEM 2018 Abstracts Book is divided into two sections: 1) Individual Presentations, and 2) Organized Sessions. Individual Presentation abstracts are alphabetized by the presenter’s last name, while Organized Session abstracts are alphabetized by the session chair’s last name. Note that Organized Sessions are designated in the Program Book as “Panel,” “Roundtable,” or “Workshop.” Sessions designated as “Paper Session” do not have a session abstract. To determine the time and location of an Individual Presentation, consult the index of participants at the back of the Program Book. To determine the time and location of an Organized Session, see the session number (e.g., 1A) in the Abstracts Book and consult the program in the Program Book. Individual Presentation Abstracts Pages 1 – 76 Organized Session Abstracts Pages 77 – 90 Society for Ethnomusicology 63rd Annual Meeting, 2018 Individual Presentation Abstracts Ethiopian Reggae Artists Negotiating Proximity to Repatriated Rastafari American Dreams: Porgy and Bess, Roberto Leydi, and the Birth of Italian David Aarons, University of North Carolina, Greensboro Ethnomusicology Siel Agugliaro, University of Pennsylvania Although a growing number of Ethiopians have embraced reggae music since the late 1990s, many remain cautious about being too closely connected to the This paper puts in conversation two apparently irreconcilable worlds. The first is repatriated Rastafari community in Ethiopia whose members promote themselves that of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935), a "folk opera" reminiscent of as reggae ambassadors. Since the 1960s, Rastafari from Jamaica and other black minstrelsy racial stereotypes, and indebted to the Romantic conception of countries have been migrating (‘repatriating’) to and settling in Ethiopia, believing Volk as it had been applied to the U.S. -

Dialogue on the Nomenclature and Classification of Prokaryotes

G Model SYAPM-25929; No. of Pages 10 ARTICLE IN PRESS Systematic and Applied Microbiology xxx (2018) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Systematic and Applied Microbiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.de/syapm Dialogue on the nomenclature and classification of prokaryotes a,∗ b Ramon Rosselló-Móra , William B. Whitman a Marine Microbiology Group, IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), 07190 Esporles, Spain b Department of Microbiology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: The application of next generation sequencing and molecular ecology to the systematics and taxonomy Bacteriological code of prokaryotes offers enormous insights into prokaryotic biology. This discussion explores some major Taxonomy disagreements but also considers the opportunities associated with the nomenclature of the uncultured Nomenclature taxa, the use of genome sequences as type material, the plurality of the nomenclatural code, and the roles Candidatus of an official or computer-assisted taxonomy. Type material © 2018 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Is naming important when defined here as providing labels Prior to the 1980s, one of the major functions of Bergey’s Manual for biological entities? was to associate the multiple names in current usage with the cor- rect organism. For instance, in the 1948 edition of the Manual, 21 Whitman and 33 names were associated with the common bacterial species now named Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, respectively [5]. When discussing the nomenclature of prokaryotes, we must first This experience illustrates that without a naming system gener- establish the role and importance of naming. -

Wayfaring Strangers: the Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 13 6-10-2015 Wayfaring Strangers: The uM sical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 361 pages. ISBN:978-1-4696-1822-7. Michael Newton University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Newton, Michael (2015) "Wayfaring Strangers: The usicalM Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 361 pages. ISBN:978-1-4696-1822-7.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 13. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Wayfaring Strangers: The Musical Voyage from Scotland and Ulster to Appalachia. Fiona Ritchie and Doug Orr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 361 pages. ISBN: 978-1-4696-1822-7. $39.95. Michael Newton, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill It has become an article of faith for many North Americans (especially white anglophones) that the pedigree of modern country-western music is “Celtic.” The logic seems run like this: country-western music emerged among people with a predominance of Scottish, Irish, and “Scotch-Irish” ancestry; Scotland and Ireland are presumably Celtic countries; ballads and the fiddle seem to be the threads of connectivity between these musical worlds; therefore, country-western music carries forth the “musical DNA” of Celtic heritage. -

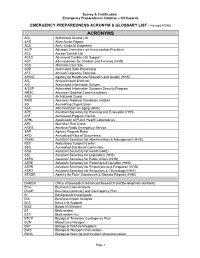

ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008

Survey & Certification Emergency Preparedness Initiative – All Hazards EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008 ACRONYMS AAL Authorized Access List AAR After-Action Report ACE Army Corps of Engineers ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices ACL Access Control List ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support ACF Administration for Children and Families (HHS) ACS Alternate Care Site ADP Automated Data Processing AFE Annual Frequency Estimate AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHS) AIE Annual Impact Estimate AIS Automated Information System AISSP Automated Information Systems Security Program AMSC American Satellite Communications ANG Air National Guard ANSI American National Standards Institute AO Accrediting Organization AoA Administration on Aging (HHS) APE Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (HHS) APF Authorized Program Facility APHL Association of Public Health Laboratories ARC American Red Cross ARES Amateur Radio Emergency Service ARF Agency Request Form ARO Annualized Rate of Occurrence ASAM Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management (HHS) ASC Ambulatory Surgical Center ASC Accredited Standards Committee ASH Assistant Secretary for Health (HHS) ASL Assistant Secretary for Legislation (HHS) ASPA Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (HHS) ASPE Assistant Secretary for Planning & Evaluation (HHS) ASPR Assistant Secretary for Preparedness & Response (HHS) ASRT Assistant Secretary for Resources & Technology (HHS) ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (HHS) BARDA