Coa St Alarchaeology in V Ic Tor Ia Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Trade Guide 2020/21

TRAVEL TRADE GUIDE 2020/21 VICTORIA · AUSTRALIA A D A Buchan To Sydney KEY ATTRACTIONS O R PHILLIP ISLAND E 1 N I P 2 WILSONS PROMONTORY NATIONAL PARK L East A 3 MOUNT BAW BAW T Mallacoota A E 4 WALHALLA HISTORIC TOWNSHIP R G 5 TARRA BULGA NATIONAL PARK A1 Croajingolong 6 GIPPSLAND LAKES Melbourne 3 National Park Mount Bairnsdale Nungurner 7 GIPPSLAND'S HIGH COUNTRY Baw Baw 8 CROAJINGOLONG NATIONAL PARK Walhalla Historic A1 4 Township Dandenong Lakes Entrance West 6 Metung TOURS + ATTRACTIONS S 6 5 Gippsland O M1 1 PENNICOTT WILDERNESS JOURNEYS U T Lakes H Tynong hc 2 GREAT SOUTHERN ESCAPES G Sale I Warragul 3 P M1 e Bea AUSTRALIAN CYCLING HOLIDAYS P S LA Trafalgar PRINCES HWY N W Mil 4 SNOWY RIVER CYCLING D H Y y Mornington et Traralgon n 5 VENTURE OUT Ni Y 6 GUMBUYA WORLD W Loch H Sorrento Central D 7 BUCHAN CAVES 5 N A L S Korumburra P P Mirboo I G ACCOMMODATION North H 1 T U 1 RACV INVERLOCH Leongatha Tarra Bulga O S 2 WILDERNESS RETREATS AT TIDAL RIVER Phillip South National Park Island 3 LIMOSA RISE 1 Meeniyan Foster 4 BEAR GULLY COTTAGES 5 VIVERE RETREAT Inverloch Fish Creek Port Welshpool 6 WALHALLA'S STAR HOTEL 3 7 THE RIVERSLEIGH 8 JETTY ROAD RETREAT 3 Yanakie Walkerville 4 9 THE ESPLANADE RESORT AND SPA 10 BELLEVUE ON THE LAKES 2 11 WAVERLEY HOUSE COTTAGES 1 2 Wilsons Promontory 12 MCMILLANS AT METUNG National Park 13 5 KNOTS Tidal River 2 02 GIPPSLAND INTERNATIONAL PRODUCT MANUAL D 2 A Buchan To Sydney O R E N 7 I P 7 L East A T Mallacoota A 8 E R 4 G A1 Croajingolong National Park Melbourne Mount Bairnsdale 11 Baw Baw 7 Nungurner -

Resource Partitioning Among Five Sympatric Mammalian Herbivores on Yanakie Isthmus, South- Eastern Australia

Resource partitioning among five sympatric mammalian herbivores on Yanakie Isthmus, south- eastern Australia Naomi Ezra Davis Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Department of Zoology The University of Melbourne i Abstract This thesis combines multiple approaches to improve our understanding of large herbivore ecology and organisation in a contemporary assemblage made up of species with independent evolutionary histories on Yanakie Isthmus, Wilsons Promontory National Park, Victoria, Australia. In particular, this thesis compares niche parameters among populations of five sympatric native and introduced herbivore species by simultaneously assessing overlap in resource use along two dimensions (spatial and trophic) at multiple scales, thereby providing insight into resource partitioning and competition within this herbivore assemblage. Faecal pellet counts demonstrated that inter-specific overlap in herbivore habitat use on Yanakie Isthmus was low, suggesting that spatial partitioning of habitat resources had occured. However, resource partitioning appeared to be independent of coevolutionary history. Low overlap in habitat use implies low competition, and the lack of clear shifts in habitat use from preferred to suboptimal habitats suggested that inter-specific competition was not strong enough to cause competitive exclusion. However, low overlap in habitat use between the European rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus and other species, and preferential use by rabbits (and avoidance by other species) of the habitat that appeared to have the highest carrying capacity, suggested that rabbits excluded other grazing herbivores from preferred habitat. High overlap in habitat use was apparent between some species, particularly grazers, indicating some potential for competition if resources are limiting. -

Wilsons Promontory, Victoria S.M

WILSONS PROMONTORY, VICTORIA S.M. Hill CRC LEME, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005 [email protected] INTRODUCTION Oberon Bay on the west coast and Waterloo Bay on the east. The The landscape of Wilsons Promontory is one of the most dramatic promontory extends southwards into the waters of Bass Strait. It in Australia. Approximately 200 km southeast of Melbourne, it forms the exposed northern section of the Bassian Rise, which is forms the southern-most part of the Australian mainland, and part for the most part a submarine ridge extending southwards from of the southern edge of the South Victorian Uplands. Granitic the South Gippsland Uplands to northeast Tasmania, dividing mountains rise from the waters of Bass Strait and host a wide the Gippsland Basin to the East and the Bass Basin to the array of granitic weathering and landscape features. Furthermore, West. A major north-south trending drainage divide forms a the coastal lowlands contain a great diversity of marine, aeolian, central “spine” extending along the length of the promontory, with colluvial and alluvial sediments that reect a dynamic Cenozoic smaller interuves mostly trending east-west along spurs which environmental history. terminate as coastal headlands between coastal embayments. Climate PHYSICAL SETTING The climate of Wilsons Promontory is generally cool and mild, Geology with few extremes. A considerable variation in rainfall across A composite batholith of Devonian granite constitutes most of the promontory is shown by the average annual rainfall for Tidal the bedrock at the promontory (Wallis, 1981; 1998). Ordovician River and Southeast Point of 1083 mm and 1050 mm respectively, metasediments occur immediately to the north and are exposed while at Yanakie it is only 808 mm. -

Rodondo Island

BIODIVERSITY & OIL SPILL RESPONSE SURVEY January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Tasmania. © Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment ISBN: 978-1-74380-006-5 (Electronic publication only) ISSN: 1838-7403 Cite as: Carlyon, K., Visoiu, M., Hawkins, C., Richards, K. and Alderman, R. (2015) Rodondo Island, Bass Strait: Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015. Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Hobart. Nature Conservation Report Series 15/04. Main cover photo: Micah Visoiu Inside cover: Clare Hawkins Unless otherwise credited, the copyright of all images remains with the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial use or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Branch Manager, Wildlife Management Branch, DPIPWE. Page | 2 RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 SUMMARY Rodondo Island was surveyed in January 2015 by staff from the Natural and Cultural Heritage Division of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) to evaluate potential response and mitigation options should an oil spill occur in the region that had the potential to impact on the island’s natural values. Spatial information relevant to species that may be vulnerable in the event of an oil spill in the area has been added to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s Oil Spill Response Atlas and all species records added to the DPIPWE Natural Values Atlas. -

Download Full Article 4.7MB .Pdf File

. https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1979.40.04 31 July 1979 VERTEBRATE FAUNA OF SOUTH GIPPSLAND, VICTORIA By K. C. Norris, A. M. Gilmore and P. W. Menkhorst Fisheries and Wildlife Division, Ministry for Conservation, Arthur Ryiah Institute for Environmental Research, 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Abstract The South Gippsland area of eastern Victoria is the most southerly part of the Australian mainland and is contained within the Bassian zoogeographic subregion. The survey area contains most Bassian environments, including ranges, river flats, swamps, coastal plains, mountainous promontories and continental islands. The area was settled in the mid 180()s and much of the native vegetation was cleared for farming. The status (both present and historical) of 375 vertebrate taxa, 50 mammals, 285 birds, 25 reptiles and 15 amphibians is discussed in terms of distribution, habitat and abundance. As a result of European settlement, 4 mammal species are now extinct and several bird species are extinct or rare. Wildlife populations in the area now appear relatively stable and are catered for by six National Parks and Wildlife Reserves. Introduction TOPOGRAPHY AND PHYSIOGRAPHY {see Hills 1967; and Central Planning Authority 1968) Surveys of wildlife are being conducted by The north and central portions of the area the Fisheries and Wildlife Division of the are dominated by the South Gippsland High- Ministry for Conservation as part of the Land lands (Strzelecki Range) which is an eroded, Conservation Council's review of the use of rounded range of uplifted Mesozoic sand- Crown Land in Victoria. stones and mudstones rising to 730 m. -

Download a History of Wilsons Promontory

A History of Wilsons Promontory by J. Ros. Garnet WITH ADDITIONAL CHAPTERS BY TERRY SYNAN AND DANIEL CATRICE Published by the Victorian National Parks Association A History of Wilsons Promontory National Park, Victoria, Australia Published electronically by the Victorian National Parks Association, May 2009, at http://historyofwilsonspromontory.wordpress.com/ and comprising: • An Account of the History and Natural History of Wilsons Promontory National Park, by J. Ros. Garnet AM. • Wilsons Promontory – the war years 1939-1945, by Terry Synan. • Wilsons Promontory National Park after 1945 [to 1998], by Daniel Catrice. Cover design and book layout by John Sampson. Special thanks to Jeanette Hodgson of Historic Places, Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria for obtaining the photos used in this book. On the cover the main photo is of Promontory visitors at Darby River bridge, c.1925. The bottom left picture shows visitors at the Darby Chalet, c.1925. To the right of that photo is a shot of field naturalist Mr Audas inspecting a grass- tree, c. 1912, and the bottom right photo is of a car stuck in sand near Darby Chalet, c.1928. © This publication cannot be reproduced without the consent of the Victorian National Parks Association. Victorian National Parks Association 3rd floor, 60 Leicester Street, Carlton, Victoria - 3053. Website: www.vnpa.org.au Phone: 03 9347 5188 Fax: 03 9347 5199 Email: [email protected] 2 A History of Wilsons Promontory Contents Foreword by Victorian National Parks Association ................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements, Preface, Introduction by J. Ros. Garnet ........................................... 6-13 Chapter 1 The European Discovery of Wilsons Promontory ...................................... -

Introduced Animals on Victorian Islands: Improving Australia’S Ability to Protect Its Island Habitats from Feral Animals

Introduced animals on Victorian islands: improving Australia’s ability to protect its island habitats from feral animals. Michael Johnston 2008 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Client Report Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Client Report Introduced animals on Victorian islands: improving Australia’s ability to protect its island habitats from feral animals Michael Johnston Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research 123 Brown Street, Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 May 2008 Prepared by Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Sustainability and Environment, for the Australian Government Department of Environment, Water Resources, Heritage and the Arts. Report produced by: Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Sustainability and Environment PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.dse.vic.gov.au/ari © State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment 2008 This publication is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical or graphic) without the prior written permission of the Sate of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment. All requests and enquires should be directed to the Customer Service Centre, 136 186 or email [email protected] Citation Johnston, M. (2008) ‘Introduced animals on Victorian -

7 Stage Wilsons Promontory, Victoria

ITINERARY Wilsons Promontory Victoria – Wilsons Promontory Multi-day walks Walking is the best way to explore the natural sanctuary of Wilsons WALK ONE – DAY ONE Promontory. Known as ‘The Prom’ to locals, it embraces 50,000 hectares WILSONS PROMONTORY CIRCUIT TRAIL of coastal wilderness on mainland Australia’s southernmost tip. The many Tidal River to Refuge Cove well-marked trails traverse empty Let your boundaries blur with nature beaches and eucalypt forest, heath and on this magical three-day circuit. Start swamp, cool rainforest gullies and rocky with a swim from the family-friendly mountain tops. Opt for short and scenic beach of Tidal River, then head east up trails, like the Loo-Errn Track, ideal for the dry, gravelly track to Windy Saddle. families and the mobility-impaired. Do a Take in the view or stop for a picnic on the day trek to the lighthouse or spend three patch of lawn that grazing animals have days on the Wilsons Promontory Circuit thoughtfully cleared in the forest. The Trail, which starts from the main tourist landscape gets wetter and greener on the hub of Tidal River. Scale Mount Oberon other side of the hill. You’ll feel alive as you or hike out to remote and beautiful descend through fern-shaded gullies and Millers Landing. Stay at campsites cross the long boardwalk-covered swamp. throughout the park and get up close Sealers Cove is largely hidden from view by to the park’s incredible array of native rocky peaks and tall eucalypts so it’s a bit of plants, birds and animals. -

Chapter 1-The European Discovery of Wilsons Promontory.Ai

Chapter 1: The European Discovery of Wilsons Promontory he European history of Wilsons Promontory began Many of them lived and died in the vicinity of Corner on the morning of 2nd January, 1798. Inlet and Shallow Inlet. T On that date George Bass and his six The days spent by Bass’s party in Sealers Cove were companions, on their famous whaleboat expedition occupied in modest inland exploration and in salting from Port Jackson to Western Port, sighted the ‘high, down mutton birds and seal meat. Bass himself was hummocky land’ which was considered to be that impressed with the place as a base from which a described by Tobias Furneaux who, in the Adventure, vigorous sealing industry could operate. The mainland had become separated from Cook during the great coast and adjacent islands harboured countless seals Second Voyage in 1773. Surely it could be nothing other and sea birds, a resource which was, in fact, thoroughly than the eastward aspect of Furneaux Land! exploited during the following decade. Bass and Flinders On the return journey from Western Port easterly are said to have taken 6000 seal skins and many tons of gales forced them to shelter in a small, quiet bay which oil from the Bass Strait colonies. By 1804 ten ships and Bass named Sealers Cove. His use of the appellation 180 men were known to be operating in the area and, by 1810, almost a quarter of a million seal skins had ‘Sealers’ rather than ‘Seal’ suggests that, perhaps, Bass was not the first mariner to have entered the Cove. -

10 Days Melbourne to Sydney Along the Princes Highway

www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental 10 days Melbourne to Sydney along the Princes Highway Melbourne Melbourne to Phillip Island Phillip Island to Wilsons Promontory National Park Wilsons Promontory to Lakes Entrance Lakes Entrance to Mallacoota Mallacoota to Merimbula Merimbula to Batemans Bay Batemans Bay to Jervis Bay Jervis Bay to Wollongong Wollongong to Sydney Distance: 1325km Day 1. Melbourne Pick up your campervan in Melbourne today. Allow 1 hour to collect and become familiar with the vehicle before you leave the branch. www.drivenow.com.au – helping travellers since 2003 find the best deals on campervan and car rental Visit the Melbourne Cricket Ground, one of Melbourne’s grandest and proudest attractions. Hosting events from Australian Rules football, cricket, concerts and the Olympics, the MCG has a proud history of great sporting and cultural moments. Experience the stadium from a player’s perspective, and visit the rooms from where they would prepare and watch the sport, and a chance to walk on the grounds. Stay: Melbourne BIG4 Holiday Park Day 2. Melbourne to Phillip Island Depart this morning and take the M1 to Pakenham. Take the C422 exit and continue onto Koo Wee Rup. Follow the M420 and B420 to Phillip Island. Phillip Island is full of nature parks with local wildlife to keep everyone entertained. Visit the Penguin Parade, one of Victoria’s most popular attractions. Each night at sunset, the Little Penguins return to the beach after a day of fishing and they are a cute sight! Watch from the boardwalks and designated viewing areas, as the penguins waddle back to their burrows. -

Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park

Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park For more information contact the Parks Victoria Information Centre on 13 1963, or visit www.parkweb.vic.gov.au Wilsons Promontory Marine Park Management Plan May 2006 This Management Plan for Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park, Marine Park and Marine Reserve is approved for implementation. Its purpose is to direct all aspects of management in the park until the plan is reviewed. A Draft Management Plan for the park was published in November 2004. Nineteen submissions were received and have been considered in developing this approved Management Plan. For further information on this plan, please contact: Chief Ranger East Gippsland Parks Victoria PO Box 483 Bairnsdale VIC 3875 Phone: (03) 5152 0669 Copies This plan may be downloaded from the Parks Victoria website ‘www.parkweb.vic.gov.au’. Copies of the plan may be purchased for $8.80 (including GST) from: Parks Victoria Information Centre Level 10, 535 Bourke Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Phone: 13 1963 Parks Victoria Orbost Office 171 Nicholson Street Orbost VIC 3888 WILSONS PROMONTORY MARINE NATIONAL PARK AND WILSONS PROMONTORY MARINE PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN May 2006 Published in May 2006 by Parks Victoria Level 10, 535 Bourke Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3000. Cover: Waterloo Bay, Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park (Photo: Mary Malloy). Parks Victoria 2006, Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park and Wilsons Promontory Marine Park Management Plan, Parks Victoria, Melbourne National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Parks Victoria Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park and Wilsons Promontory Marine Park Management Plan. Bibliography. Includes index ISBN 0 7311 8346 0 1. -

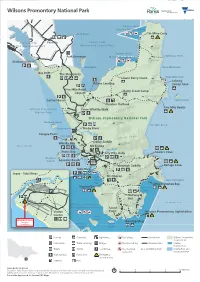

Wilsons Promontory National Park Map Overview (PDF)

Wilsons Promontory National Park M E E N I YA N Corner Inlet -P R O M Marine National Park O N T Tin Mine Cove O Duck Point R Y RD Shallow Inlet Yanakie Corner Inlet D R Marine and Coastal Park Marine and Coastal Park Y E MT HUNTER L O 347M RD F R Corner Inlet A L Lighthouse Point IL Park Entrance Marine National Park M MT MARGARET Shallow Inlet 218M Long Island Three Mile Beach Big Drift The Stockyards Lower Barry Creek Three Mile Point MT ROUNDBACK Johnny 316M Millers Landing Souey Cove Five Mile Road W Barry Creek Camp IL S Carpark O N MT SUGARLOAF S 98M Rabbit Island Cotters Beach D R E IL Vereker Outlook FIVE M Five Mile Beach Wilsons Promontory Cotters Prom Wildlife Walk Marine Park VEREKER RANGE Lake P R O M O N Wilsons Promontory National Park T O R Shellback Island Y MT VEREKER 586M Five Mile Beach Darby Beach Darby River Darby R Tongue Point D River Fairy Cove LATROBE RANGE Darby Saddle Whisky Bay MT LATROBE Bass Strait Mt Bishop 754M Tidal River Picnic Bay Sealers Cove 319M Lilly Pilly Gully MT RAMSAY Norman 679M Squeaky Beach MT MCALISTER Island 453M Telegraph Saddle Refuge Cove Tidal River 558M Inset - Tidal River WILSON RANGE Little Mt Oberon MT WILSON KERSOPS 705M PEAK Oberon Cape Wellington Bay Little Waterloo Bay Oberon Bay TELEGRAPH Waterloo JUNCTION T E Bay L E MT NORGATE G Tidal River 419M R Halfway A P H BOULDERHut RING RD T K RANGE Tasman Sea Wilsons Promontory Marine National Park South Visitor Point Wilsons Promontory Lightstation Centre Anser Island Roaring Meg Kanowna Wattle Island Island Parking Camping Lighthouse No fishing Sealed road Wilsons Promontory National Park Information Trailer camping Bridge No spearfishing Unsealed road Marine Narional Park Toilets Cabins Foot bridge No shell/crab Walking track Marine Park and collecting Coastal Reserve Walking track Picnic area Emergency assembly area Lookout Fuel www.parks.vic.gov.au Disclaimer: Parks Victoria does not guarantee that this data is without flaw of any kind and therefore disclaims all 0 3 6 9 12 Kilometres liability which may arise from you relying on this information.