Judging Cruelty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tamwag Fawf000053 Lo.Pdf

A LETTER FROM AMERICA By Pam Flett- WILL be interested in hearing what you think of Roosevelt’s foreign policy. When he made the speech at Chicago, I was startled and yet tremendously thrilled. It certainly looks as if something will have to be done to stop Hitler and Mussolini. But I wonder what is behind Roosevelt's speech. What does he plan to do? And when you get right down to it, what can we do? It’s easy to say “Keep out of War,” but how to keep out? TREAD in THE FIGHT that the ‘American League is coming out with a pamphlet by Harty F. Ward on this subject—Neutrality llready and an American sent in Peace my order. Policy. You I’ve know you can hardly believe anything the newspapers print these days_and I’m depending gare end ors on hare caer Phiets. For instance, David said, hational, when we that read i¢ The was Fascist_Inter- far-fetched and overdone. But the laugh’s for on him, everything if you can that laugh pamphlet at it- Fe dered nigiae th fact, the pamphiot is more up- iendalainow than Fodey'eipener eso YOUR NEXT YEAR IN ART BUT I have several of the American League pamphlets—Women, War and Fascism, Youth Demands WE'VE stolen a leaf from the almanac, which not only tells you what day it is but gives you Peace, A Blueprint for Fascism advice on the conduct of life. Not that our 1938 calendar carries instructions on planting-time (exposing the Industrial Mobiliza- tion Plan)—and I’m also getting But every month of it does carry an illustration that calls you to the struggle for Democracy and Why Fascism Leads to War and peace, that pictures your fellow fighters, and tha gives you a moment’s pleasure A Program Against War and Fascism. -

University of New Mexico Board of Regents Minutes for May 10, 1996 University of New Mexico Board of Regents

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Board of Regents Meeting Minutes University of New Mexico Board of Regents 5-10-1996 University of New Mexico Board of Regents Minutes for May 10, 1996 University of New Mexico Board of Regents Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/bor_minutes Recommended Citation University of New Mexico Board of Regents. "University of New Mexico Board of Regents Minutes for May 10, 1996." (1996). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/bor_minutes/831 This Minutes is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Board of Regents at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Board of Regents Meeting Minutes by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF • THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO May 10, 1996 The Regents ofthe University ofNew Mexico met on Friday, May 10, 1996, in the Roberts Room ofScholes Hall. A copy ofthe public notice ofthe meeting is on file in the Office ofthe President. Regents Present: Penny Taylor Rembe, President Barbara G. Brazil, Vice President Eric A. Thomas, Secretary/Treasurer J.E. (Gene) Gallegos Mary A. Tang Larry D. Willard Regents Absent: Arthur D. Melendres Also Present: Advisors to the Regents • Harry Uull, President, Faculty Senate Velma Morgan, President, StaffCouncil Michelle Polk, President, Alumni'Association Ray Sharbutt, President, Graduate and Professional Students Association Alberto Solis, President, Associated Students ofUNM Members ofthe Administration, the media and others Absent: Richard Morris, President, UNM Foundation ******* Regent President Penny Taylor Rembe called the meeting to order at 1:09 p.m. -

Annual Firearms Manufacturing and Export Report 2018 Final

ANNUAL FIREARMS MANUFACTURING AND EXPORT REPORT YEAR 2018 Final* MANUFACTURED PISTOLS REVOLVERS TO .22 417,806 TO .22 271,553 TO .25 25,370 TO .32 1,100 TO .32 30,306 TO .357 MAG 113,395 TO .380 760,812 TO .38 SPEC 199,028 TO 9MM 2,099,319 TO .44 MAG 42,436 TO .50 547,545 TO .50 37,323 TOTAL 3,881,158 TOTAL 664,835 RIFLES 2,880,536 SHOTGUNS 536,126 MISC. FIREARMS 1,089,973 EXPORTED PISTOLS 333,266 REVOLVERS 21,498 RIFLES 165,573 SHOTGUNS 27,774 MISC. FIREARMS 6,126 * FOR PURPOSES OF THIS REPORT ONLY, "PRODUCTION" IS DEFINED AS: FIREARMS, INCLUDING SEPARATE FRAMES OR RECEIVERS, ACTIONS OR BARRELED ACTIONS, MANUFACTURED AND DISPOSED OF IN COMMERCE DURING THE CALENDAR YEAR. PREPARED BY LED 01/28/2020 REPORT DATA AS OF 01/28/2020 PISTOLS MANUFACTURED IN 2018 PAGE 1 OF 128 PISTOL PISTOL PISTOL PISTOL PISTOL PISTOL PISTOL RDS KEY LICENSE NAME STREET CITY ST 22 25 32 380 9MM 50 TOTAL 99202128 BOWMAN, FORREST WADE 29 COLLEGE RD #8B-2 FAIRBANKS AK 0 5 0 0 0 1 6 99202850 DOWLE, PAUL GORDON 1985 LARIX DR NORTH POLE AK 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 99203038 EVERYDAY DEFENSE 1591 N KERRY LYNN LN WASILLA AK 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 SOLUTIONS LLC 99202873 HAWK SHOP LLC 2117 S CUSHMAN ST FAIRBANKS AK 2 0 1 0 4 11 18 99202968 HOBBS, THOMAS CHARLES 3851 MARIAH DRIVE EAGLE RIVER AK 0 0 0 6 1 0 7 16307238 ANDERSONS GUNSMITHING 4065 COUNTY ROAD 134 HENAGAR AL 4 0 2 0 0 0 6 AND MACHINING LLC 16307089 BARBOUR CREEK LLC 200 SELF RD EUFAULA AL 0 0 0 1 14 0 15 16307641 BOTTA, PAUL EDWARD 10040 BUTTERCREME DR MOBILE AL 0 2 0 0 0 0 2 S 16303219 CHATTAHOOCHEE GUN 312 LEE RD 553 PHENIX CITY -

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc. Visual Materials BIOGRAPHY A Abeyta family Abbott, Emma Abbott, Hellen Abbott, Stephen S. Abernathy, Ralph (Rev.) Abot, Bessie SEE: Oversize photographs Abreu, Charles Acheson, Dean Gooderham Acker, Henry L. Adair, Alexander Adami, Charles and family Adams, Alva (Gov.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) (Adams, Elizabeth Matty) Adams, Alva Blanchard Jr. Adams, Andy Adams, Charles Adams, Charles Partridge Adams, Frederick Atherton and family Adams, George H. Adams, James Capen (“Grizzly”) Adams, James H. and family Adams, John T. Adams, Johnnie Adams, Jose Pierre Adams, Louise T. Adams, Mary Adams, Matt Adams, Robert Perry Adams, Mrs. Roy (“Brownie”) Adams, W. H. SEE ALSO: Oversize photographs Adams, William Herbert and family Addington, March and family Adelman, Andrew Adler, Harry Adriance, Jacob (Rev. Dr.) and family Ady, George Affolter, Frederick SEE ALSO: oversize Aichelman, Frank and Agnew, Spiro T. family Aicher, Cornelius and family Aiken, John W. Aitken, Leonard L. Akeroyd, Richard G. Jr. Alberghetti, Carla Albert, John David (“Uncle Johnnie”) Albi, Charles and family Albi, Rudolph (Dr.) Alda, Frances Aldrich, Asa H. Alexander, D. M. Alexander, Sam (Manitoba Sam) Alexis, Alexandrovitch (Grand Duke of Russia) Alford, Nathaniel C. Alio, Giusseppi Allam, James M. Allegretto, Michael Allen, Alonzo Allen, Austin (Dr.) Allen, B. F. (Lt.) Allen, Charles B. Allen, Charles L. Allen, David Allen, George W. Allen, George W. Jr. Allen, Gracie Allen, Henry (Guide in Middle Park-Not the Henry Allen of Early Denver) Allen, John Thomas Sr. Allen, Jules Verne Allen, Orrin (Brick) Allen, Rex Allen, Viola Allen William T. -

Directory for Reaching Minority Groups. NSTITUTION Manpower Administration (DOL), Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 356 VT 013 468 TITLE Directory for Reaching Minority Groups. NSTITUTION Manpower Administration (DOL), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Apprenticeship and Training. IVB DATE 70 HOTE 259 p. 4VAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (L23.2:/466, $2. 00) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price NF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS *Agencies, Communications, *Directories, *Employment Opportunities, Information Sources, *Information Systems, Manpower Utilization, *Minority Groups, Vocational Education ABSTRACT This directory lists, alphabetically by state and city, the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of the organizations and people who are able to reach minority groups to tell them about affirmative action programs for job training and job opportunities. At the end o.2 many of the state entries are listed organizations which have statewide or regionwide contacts with special groups, such as Indians and Spanish-speaking persons. (Author) 2 . - 0 . % a0 s NNW V U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE **0 OFFICE OF EDUCATION Lr4 THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- (-NJ IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. Directory 4 for 4, it eaching Minority Groups U.S. DEPARTMENTOF LABOR J.D. Hodgson, Secretary MANPOWER ADMINISTRATION BUREAU OF APPRENTICESHIP AND TRAINING 1970 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office O Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2 rl PREFACE This directory lists, alphabetically by State and city, the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of theor- ganizations and people who are able to reach minority groups to tell them about affirmative action programs for job training and job opportunities. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 39 No. 122, October 5, 2007

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 10-5-2007 Central Florida Future, Vol. 39 No. 122, October 5, 2007 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 39 No. 122, October 5, 2007" (2007). Central Florida Future. 2035. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/2035 • () FREE • Published Mondays, Wednesda :sand Frida :s www.CentralFloridaFuture.com ·Friday, October 5, 2007 I) Pirate adventure Knights head to East Carolina looking to extend their winning ways -SEESPORTS,A7 ) Medical ci BREAKS GROUN ) More than 500 attended ceremony ROBYN SIDERSKY university's first building. Staff Writer "It doesn't get any better," German said. "It's a celebra UCF officials broke tion of the birth of our med ground Wednesday at Lake ical city." Nona, the planned home of The Burnham Institute for UCF's College of Medicine Medical Research will house NICOLE STANCEL I CENTRAL FLORIDA FUTURE and a medical city. UCF's' College of Medicine President John Hitt and Student Government Association President Brandie Hollinger are among others who were part of the dirt-turning With more than 500 Cen and the emerging life sciences ceremony at Lake Nona. -

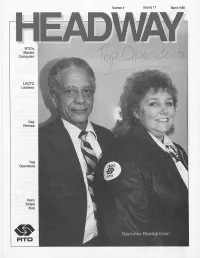

Headway March 1989

Number 3 Volume 17 March 1989 RTD's Master Computer LACTC Leaders Day Retires Top Operators Hero Stops Bus Operator Recognition 9rABLE 0FCONTENTS RTD Ridership, Revenues Higher Than Forecast Master Computer Controls Metro Rail Reed Takes LACTC Chair RTD is in a highly stable and sound financial condition in mid-year of its fiscal operation, announced General Manager LACTC Gets New Head Man Pegg in mid-Febuary. This is the result of RTD ridership and passenger Annual Report Issued for FY 1987-88 revenues having been higher than anticipated during the first half of fiscal year 1989. With these trends continuing Director Day Retires From RTD Board through June 30, RTD will Finish FY 1989 with a balanced budget, Pegg said. Top Operators "System-wide patronage was up almost 12 million riders to 201 million during the first half of FY 1989, compared to a Moving the Post Office projected 189 million passengers," he said. As a result, RTD passenger revenues increased $8.1 Vaughn Named Operator of the Month million to $113 million, as compared to the forecast of $104 million in the same period, he added. Blood Donor Honor Roll Pegg noted other highlights regarding patronage and revenues since the new fare structure started an July 1, Vasquez Chosen Info Operator of the Year 1988. "While there was a slight decline in overall boarding of 3.9 percent, or 8.2 million passengers, there was at the "Fresh Savings" Kick Off at Galleria same time a net increase in passenger revenue of 24.8 percent, or $22.5 million," he said. -

Records of the Connecticut Line of the Hayden Family

RECORDS OF THE Connecticut Line OF THE HAYDEN FAMILY By Jabez leisKell Hayder?, j^^» IZ ?^r v^ *. OF WINDSOR LOCKS, CONN., XBBB. CADHAY HALL,built by John Haydon, 1536-1550, reign of Henry VIM. 6*r TO MY SISTER LUCINDA HASKELL HAYDEN, OF HAYDENS, Who was greeted iq infancy by oqe of trje Patriarchs of the FamHy who had kqown all tqe Connecticut borq Haydeqs who had preceded him, including Daniel, borq 1640, and all trjose w^o, a century later, emigrated from Haydens "to trje — West," wl]o has, herself, knowq all tl^e families of th,e succeeding generations of those wrjo have remained in tj-je neighborhood of the old homestead, aqd is a Worthy Representative OF AN HONORED ANCESTRY, This volume is Affectionately Dedicated. RECORDS OF THE Connecticut Line OF THE HAYDEN FAMILY By Jabez leisKell Hayder?, j^^» IZ ?^r v^ *. OF WINDSOR LOCKS, CONN., XBBB. The Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company PRINTERS AND BINDERS 1888 Copyright, 1888, Jabez Haskell Hayden.' PREFACE. The author was born in Windsor, Conn., in a neighborhood then called Haydentown, now Haydens, where his line of the family had lived from the time of the first William. In1840, during a season of comparative leisure, Iset out to find who my Hayden ancestors were before my great grandfather, Deacon Nathaniel Hayden, who was known to many then living. "AuntOlive," the widow of Ezra, had an impression that the deacon's father's name was Samuel, and his wife Ann. With this clue Iwent to the town records, and found the work less difficult and far more interesting than Ianticipated. -

Here, Have Potent Implications for International Affairs

“Today we use the term ‘the world’ with what amounts to brash familiarity. Too often in speaking of such things as the world food problem, the world health problem, world trade, world peace, and world government, we disregard the fact that ‘the world’ is a totality which in the domain of human problems constitutes the ultimate in degree of magnitude and degree of complexity. That is a fact, yes; but another fact is that almost every large problem today is, in truth, a world problem. Those two facts taken together provide thoughtful men with what might realistically be entitled ‘an introduction to humility’ in curing the world’s ills.” — President Emeritus John Sloan Dickey, 1947 Convocation Address World Outlook An Undergraduate Journal of International Affairs at Dartmouth College Editors-in-Chief Charles Bateman ‘22 Ben Vagle ‘22 Senior Editors Caleb Benjamin ’23 Jesse Ferraioli ’23 Ian Gill ’23 Sam LeLacheur ’23 Kristabel Konta ’24 Adam Salzman ‘24 Staff Editors Paul Keller ’23 Joseph Fausey ’23 Rothschild Toussaint ’23 Rujuta Pandit ’24 Matt Capone ’24 Halle Troadec ’24 Sri Sathvik Rayala ’24 Hannah Dunleavy ’24 Wenhan Sun ‘24 The Editors of World Outlook would like to express gratitude to the John Sloan Dickey Center for its encouragement and assistance. Founders Timothy E. Bixby ’87 Peter M. Lehmann ’85 Anne E. Eldridge ’87 Mark C. Henrie ’87 Peter D. Murane ’87 About the Journal: World Outlook is a student-run journal of international affairs that publishes papers writ- ten by undergraduate students. In addition, the journal features interviews with major global thinkers and opinion pieces written by our own staff. -

May 2012 News Releases

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 5-1-2012 May 2012 news releases University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "May 2012 news releases" (2012). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 22144. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/22144 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - UM News - The University Of Montana my.umt.edu A to Z Index Directory UM Home May 2012 News 05/31/2012 - UM Law Professor Named Appellate Lawyer Of The Week - Anthony Johnstone 05/30/2012 - UM Graduate Receives Prestigious National Award - Diane Rapp 05/30/2012 - Ireland's Dublin City Ramblers To Play Inaugural Philipsburg Celtic Festival - Traolach O’Riordain 05/30/2012 - UM Student Award Inaugural Tricia Moen Memorial Scholarship - Denise Dowling 05/24/2012 - Report Finds Number Of Montana Children Raised By Relatives, Family Friends Doubles Over Decade - Thale Dillon 05/22/2012 - MMAC Celebrates -

March, 1962 Page Three • ': Field Surv~Y Notes

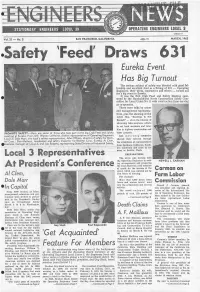

OPERATING ENGINEERS. LOCAL 3 . ~637 Vol. 21 - No. 3 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFOR~IA ~ 151 MARCH, . 1962 -Safety, 'Feed' DraWs 6,31 Eureka Everit Has -Big Turnout . .._, The serious subject of saf~ty'· was blended with good fel low~hip .and exc.ellent food as a throng of 631 - Operating Engineers, their wives, contractors and others - turned out for a big event in Eureka. ·- · . I · It was the first Crab Feed_ and Safety Meeting -spon sored by the Humboldt-Del Norte Construction·safety Com mittee_for Local Unio:q. No . 3, with construction firms se_rvil1g as co-sponsors. .. There w~re talks by union ~nd management ·representa tives, plus the showing of the safety film, '~:Knowin·g . Is · Not Enough" - all in the interest of ad-vancing labor-employer efforts to cut back accidents and fatal- ities in highway construction and PROMO .f~:- SAFETY:-- He.re , are ·som·e ·of those who took part in -the big Crab Feed and Safety other p~ojects . " r:n~eting at.· Eureka. Fr.dm left: Warren LeMoine, district representative, of Operating Engineers And i 1) sur an c e- companies Locai 3;- D,ale Marr>the local 's safety representative; John·O' Bi-ien, director of safety for Bec h - their ·inlerest through 1 showed tel C.or:p:,: Dilh M_ ilthers. ,·· tin1eke¢per· aAd safety inspeCtor:. for-Bechtel Corp., Eureka; AI Clem, - · · the attendance of representatives · • .busi:ne~ . s : m~_ nagel of kscal :3 / ·an'd ~oe . ~oberts, r;epresen~ing State. Di\ds !~_....n .of l,ndustri_al Safety. _ . _ _ , . -

State Man Seized by Iraqis

lA iianrhpstpr HrralJi Weekend Edition, October 27,1990 Voted 1990 New England Newspaper of the Vbar Newsstand Price: 35 Cents State man seized by Iraqis By LAURA KING The Associated Press BAGHDAD, Iraq — Iraqi occupation forces have seized two Americans who had been hiding in Kuwait to avoid capture, Western diplomats disclosed Friday. Uwc Jahnkc, 47, of Washington Depot, Conn., and John Stevenson, 44, of Panama City, Fla., were brought to Baghdad on Oct. 22, a day after their arrest in Kuwait, said the diplomats, who spoke on condition of anonymity. They said the pair was taken to the government-run Mansour-Melia Hotel, where scores of other foreigners are being held. Baghdad has refused to allow thousands of foreigners trapped by Iraq’s Aug. 2 invasion of Kuwait to leave. Foreign women and children were eventually allowed to depart, and some men were released at the intervention of officials from their governments. But hundreds of others, including more than 1(X) Americans, were sent to strategic installations to deter a possible attack by U.S.-led multinational forces that as sembled in Saudi Arabia after the invasion. Western diplomats were allowed access to the recently captured Americans, tiicy said. “They’re obviously upset at being held by the Iraqi authorities but otherwise they’re just fine,” one diplomat said. The sources said Jahnke had worked with an invest ment company in Kuwait and Stevenson was an Raglnald Plnto/ltanch«ator Harald employee of the Bank of Kuwait. GOODBYE TO DAYLIGHT-SAVING — Don’t forget to turn your clock back one hour before Jalmkc’s wife, who refused to give her full name, said in a telephone interview from her Connecticut home that you go to sleep Saturday night or by 2 a.m., Sunday morning, which is when daylight-saving ends.