PNACJ008.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alfalfa PMG 12 19 11

UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines: ALFALFA September 2010 Contents (Dates in parenthesis indicate when each topic was updated) Alfalfa Year-Round IPM Program Checklist (11/06) ........................................................................................................................ iv General Information Integrated Pest Management (11/06) ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Selecting the Field (11/06) ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Transgenic Herbicide-Tolerant Alfalfa (11/06) ................................................................................................................................... 3 Biological Control (11/06) ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Sampling with a Sweep Net (11/06) .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Crop Rotation (11/06) .......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Aphid Monitoring (9/07) ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Breeding Virus Resistant Potatoes (Solanum Tuberosum): a Review of Traditional and Molecular Approaches

Heredity 86 (2001) 17±35 Received 22 December 1999, accepted 20 September 2000 Breeding virus resistant potatoes (Solanum tuberosum): a review of traditional and molecular approaches RUTH M. SOLOMON-BLACKBURN* & HUGH BARKER Scottish Crop Research Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, Scotland, U.K. Tetraploid cultivated potato (Solanum tuberosum) is the World's fourth most important crop and has been subjected to much breeding eort, including the incorporation of resistance to viruses. Several new approaches, ideas and technologies have emerged recently that could aect the future direction of virus resistance breeding. Thus, there are new opportunities to harness molecular techniques in the form of linked molecular markers to speed up and simplify selection of host resistance genes. The practical application of pathogen-derived transgenic resistance has arrived with the ®rst release of GM potatoes engineered for virus resistance in the USA. Recently, a cloned host virus resistance gene from potato has been shown to be eective when inserted into a potato cultivar lacking the gene. These and other developments oer great opportunities for improving virus resistance, and it is timely to consider these advances and consider the future direction of resistance breeding in potato. We review the sources of available resistance, conventional breeding methods, marker-assisted selection, somaclonal variation, pathogen-derived and other transgenic resistance, and transformation with cloned host genes. The relative merits of the dierent methods are discussed, and the likely direction of future developments is considered. Keywords: breeding, host gene, potato virus, resistance, review, transgenic. The viruses whether the infection is primary (current season infec- tion) or secondary (tuber-borne). -

Thrips-Transmitted Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus (TSWV) in California Crops

Emergence and integrated management of thrips-transmitted Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) in California crops UCCE-Monterey County; 2015 Plant Disease Seminar November 4, 2015; County of Monterey Agricultural Center; Salinas, California Ozgur Batuman Department of Plant Pathology, UC Davis California Processing Tomatoes And Peppers • Today, California grows 95 percent of the USA’s processing tomatoes and approximately 30 percent of the world processing tomatoes production! • California produced 60 and 69 percent of the bell peppers and chile peppers, respectively, grown in the USA in 2014! Pepper-infecting viruses • ~70 viruses known to infect peppers worldwide • ~10 of these known to occur in California • Most are not seed-transmitted • Difficult to identify based on symptoms • Mixed infections are common • Transmitted from plant-to-plant by various insects, primarily aphids and thrips • Best managed by an IPM approach TSWV Key viruses affecting peppers in CA production areas • Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) Alfamovirus • Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) Cucumovirus • Pepper mottle virus (PepMoV) Potyvirus Aphid • Potato virus Y (PVY) Potyvirus • Tobacco etch virus (TEV) Potyvirus • Pepper mild mottle virus (PMMV) Tobamovirus • Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) Tobamovirus Seed & Mechanical • Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV) Tobamovirus • Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) Tospovirus Thrips • Impatient necrotic spot virus (INSV) Tospovirus • Beet curly top virus (BCTV) Curtovirus Leafhopper *Whitefly-transmitted geminiviruses in peppers are not present in -

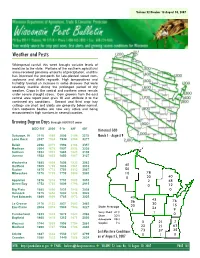

Weather and Pests

Volume 52 Number 18 August 10, 2007 Weather and Pests Widespread rainfall this week brought variable levels of moisture to the state. Portions of the southern agricultural areas received generous amounts of precipitation, and this has improved the prospects for late-planted sweet corn, soybeans and alfalfa regrowth. High temperatures and humidity favored an increase in some diseases that were relatively inactive during the prolonged period of dry weather. Crops in the central and northern areas remain under severe drought stress. Corn growers from the east central area report poor grain fill and attribute it to the continued dry conditions. Second and third crop hay cuttings are short and yields are generally below normal. Corn rootworm beetles are now very active and being encountered in high numbers in several counties. Growing Degree Days through 08/09/07 were GDD 50F 2006 5-Yr 48F 40F Historical GDD Dubuque, IA 2115 1989 2006 2194 3379 March 1 - August 9 Lone Rock 2037 1924 1934 2058 3277 Beloit 2098 2071 1996 2106 3357 Madison 2004 1879 1907 2028 3236 Sullivan 1932 1912 1883 1923 3139 Juneau 1922 1803 1850 1967 3127 Waukesha 1885 1804 1806 1933 3083 Hartford 1909 1789 1803 1961 3010 40 50 Racine 1875 1774 1751 1912 3067 Milwaukee 1870 1785 1739 1906 3063 10 78 20 40 0 Appleton 1876 1818 1731 1909 3051 2 48 Green Bay 1752 1703 1609 1798 2915 0 12 Big Flats 1885 1890 1831 1846 3058 0 Hancock 1875 1858 1802 1836 3026 Port Edwards 1869 1899 1765 1873 3035 43 45 36 76 La Crosse 2178 2133 2037 2063 3462 30 20 15 Eau Claire 2004 2078 1903 1982 3227 State Average 24 9 Very Short 41% 1 Cumberland 1833 1828 1679 1822 2986 1 0 Short 32% Bayfield 1465 1478 1312 1471 2500 Adequate 26% 5 2 Wausau 1744 1689 1598 1754 2861 Surplus 1% 21 Medford 1690 1707 1568 1708 2804 22 21 63 35 Soil Moisture Conditions 73 57 Crivitz 1687 1638 1530 1727 2799 0 0 1 Crandon 1588 1522 1449 1568 2634 as of August 5, 2007 WEB: http://pestbulletin.wi.gov z EMAIL: [email protected] z VOLUME 52 Issue No. -

Download The

9* PSEUDORECOMBINANTS OF CHERRY LEAF ROLL VIRUS by Stephen Michael Haber B.Sc. (Biochem.), University of British Columbia, 1975 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (The Department of Plant Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July, 1979 ©. Stephen Michael Haber, 1979 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Plant Science The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date Jul- 27. 1Q7Q ABSTRACT Cherry leaf roll virus, as a nepovirus with a bipartite genome, can be genetically analysed by comparing the properties of distinct 'parental' strains and the pseudorecombinant isolates generated from them. In the present work, the elderberry (E) and rhubarb (R) strains were each purified and separated into their middle (M) and bottom (B) components by sucrose gradient centrifugation followed by near- equilibrium banding in cesium chloride. RNA was extracted from the the separated components by treatment with a dissociation buffer followed by sucrose gradient centrifugation. Extracted M-RNA of E-strain and B-RNA of R-strain were mixed and inoculated to a series of test plants as were M-RNA of R-strain and B-RNA of E-strain. -

A Metagenomic Approach to Understand Stand Failure in Bromus Tectorum

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2019-06-01 A Metagenomic Approach to Understand Stand Failure in Bromus tectorum Nathan Joseph Ricks Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ricks, Nathan Joseph, "A Metagenomic Approach to Understand Stand Failure in Bromus tectorum" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 8549. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8549 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Metagenomic Approach to Understand Stand Failure in Bromus tectorum Nathan Joseph Ricks A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Craig Coleman, Chair John Chaston Susan Meyer Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences Brigham Young University Copyright © 2019 Nathan Joseph Ricks All Rights Reserved ABSTACT A Metagenomic Approach to Understand Stand Failure in Bromus tectorum Nathan Joseph Ricks Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, BYU Master of Science Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) is an invasive annual grass that has colonized large portions of the Intermountain west. Cheatgrass stand failures have been observed throughout the invaded region, the cause of which may be related to the presence of several species of pathogenic fungi in the soil or surface litter. In this study, metagenomics was used to better understand and compare the fungal communities between sites that have and have not experienced stand failure. -

Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Longidorus Americanum N

Journal of Nematology 37(1):94–104. 2005. ©The Society of Nematologists 2005. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Longidorus americanum n. sp. (Nematoda: Longidoridae), aNeedle Nematode Parasitizing Pine in Georgia Z. A. H andoo, 1 L. K. C arta, 1 A. M. S kantar, 1 W. Y e , 2 R. T. R obbins, 2 S. A. S ubbotin, 3 S. W. F raedrich, 4 and M. M. C ram4 Abstract: We describe and illustrate anew needle nematode, Longidorus americanum n. sp., associated with patches of severely stunted and chlorotic loblolly pine, ( Pinus taeda L.) seedlings in seedbeds at the Flint River Nursery (Byromville, GA). It is characterized by having females with abody length of 5.4–9.0 mm; lip region slightly swollen, anteriorly flattened, giving the anterior end atruncate appearance; long odontostyle (124–165 µm); vulva at 44%–52% of body length; and tail conoid, bluntly rounded to almost hemispherical. Males are rare but present, and in general shorter than females. The new species is morphologically similar to L. biformis, L. paravineacola, L. saginus, and L. tarjani but differs from these species either by the body, odontostyle and total stylet length, or by head and tail shape. Sequence data from the D2–D3 region of the 28S rDNA distinguishes this new species from other Longidorus species. Phylogenetic relationships of Longidorus americanum n. sp. with other longidorids based on analysis of this DNA fragment are presented. Additional information regarding the distribution of this species within the region is required. Key words: DNA sequencing, Georgia, loblolly pine, Longidorus americanum n. sp., molecular data, morphology, new species, needle nematode, phylogenetics, SEM, taxonomy. -

The Leafhoppers of Minnesota

Technical Bulletin 155 June 1942 The Leafhoppers of Minnesota Homoptera: Cicadellidae JOHN T. MEDLER Division of Entomology and Economic Zoology University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station The Leafhoppers of Minnesota Homoptera: Cicadellidae JOHN T. MEDLER Division of Entomology and Economic Zoology University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Accepted for publication June 19, 1942 CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Acknowledgments 3 Sources of material 4 Systematic treatment 4 Eurymelinae 6 Macropsinae 12 Agalliinae 22 Bythoscopinae 25 Penthimiinae 26 Gyponinae 26 Ledrinae 31 Amblycephalinae 31 Evacanthinae 37 Aphrodinae 38 Dorydiinae 40 Jassinae 43 Athysaninae 43 Balcluthinae 120 Cicadellinae 122 Literature cited 163 Plates 171 Index of plant names 190 Index of leafhopper names 190 2M-6-42 The Leafhoppers of Minnesota John T. Medler INTRODUCTION HIS bulletin attempts to present as accurate and complete a T guide to the leafhoppers of Minnesota as possible within the limits of the material available for study. It is realized that cer- tain groups could not be treated completely because of the lack of available material. Nevertheless, it is hoped that in its present form this treatise will serve as a convenient and useful manual for the systematic and economic worker concerned with the forms of the upper Mississippi Valley. In all cases a reference to the original description of the species and genus is given. Keys are included for the separation of species, genera, and supergeneric groups. In addition to the keys a brief diagnostic description of the important characters of each species is given. Extended descriptions or long lists of references have been omitted since citations to this literature are available from other sources if ac- tually needed (Van Duzee, 1917). -

Viral Diseases of Soybeans

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 60: Viral Diseases of Soybeans Marie A.C. Langham ([email protected]) Connie L. Strunk ([email protected]) Four soybean viruses infect South Dakota soybeans. Bean Pod Mottle Virus (BPMV) is the most prominent and causes significant yield losses. Soybean Mosaic Virus (SMV) is the second most commonly identified soybean virus in South Dakota. It causes significant losses either in single infection or in dual infection with BPMV. Tobacco Ringspot Virus (TRSV) and Alfalfa Mosaic Virus (AMV) are found less commonly than BPMV or SMV. Managing soybean viruses requires that the living bridge of hosts be broken. Key components for managing viral diseases are provided in Table 60.1. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the symptoms, vectors, and management of BPMV, SMV, TRSV, and AMV. Table 60.1. Key components to consider in viral management. 1. Viruses are obligate pathogens that cannot be grown in artificial culture and must always pass from living host to living host in what is referred to as a “living or green” bridge. 2. Breaking this “living bridge” is key in soybean virus management. a. Use planting dates to avoid peak populations of insect vectors (bean leaf beetle for BPMV and aphids for SMV). b. Use appropriate rotations. 3. Use disease-free seed, and select tolerant varieties when available. 4. Accurate diagnosis is critical. Contact Connie L. Strunk for information. (605-782-3290 or [email protected]) 5. Fungicides and bactericides cannot be used to manage viral problems. 60-541 extension.sdstate.edu | © 2019, South Dakota Board of Regents What are viruses? Viruses that infect soybeans present unique challenges to soybean producers, crop consultants, breeders, and other professionals. -

Ventura County Plant Species of Local Concern

Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants (Twenty-second Edition) CNPS, Rare Plant Program David L. Magney Checklist of Ventura County Rare Plants1 By David L. Magney California Native Plant Society, Rare Plant Program, Locally Rare Project Updated 4 January 2017 Ventura County is located in southern California, USA, along the east edge of the Pacific Ocean. The coastal portion occurs along the south and southwestern quarter of the County. Ventura County is bounded by Santa Barbara County on the west, Kern County on the north, Los Angeles County on the east, and the Pacific Ocean generally on the south (Figure 1, General Location Map of Ventura County). Ventura County extends north to 34.9014ºN latitude at the northwest corner of the County. The County extends westward at Rincon Creek to 119.47991ºW longitude, and eastward to 118.63233ºW longitude at the west end of the San Fernando Valley just north of Chatsworth Reservoir. The mainland portion of the County reaches southward to 34.04567ºN latitude between Solromar and Sequit Point west of Malibu. When including Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands, the southernmost extent of the County occurs at 33.21ºN latitude and the westernmost extent at 119.58ºW longitude, on the south side and west sides of San Nicolas Island, respectively. Ventura County occupies 480,996 hectares [ha] (1,188,562 acres [ac]) or 4,810 square kilometers [sq. km] (1,857 sq. miles [mi]), which includes Anacapa and San Nicolas Islands. The mainland portion of the county is 474,852 ha (1,173,380 ac), or 4,748 sq. -

View a Copy of This Licence, Visit

Hilton et al. Microbiome (2021) 9:19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00972-0 RESEARCH Open Access Identification of microbial signatures linked to oilseed rape yield decline at the landscape scale Sally Hilton1* , Emma Picot1, Susanne Schreiter2, David Bass3,4, Keith Norman5, Anna E. Oliver6, Jonathan D. Moore7, Tim H. Mauchline2, Peter R. Mills8, Graham R. Teakle1, Ian M. Clark2, Penny R. Hirsch2, Christopher J. van der Gast9 and Gary D. Bending1* Abstract Background: The plant microbiome plays a vital role in determining host health and productivity. However, we lack real-world comparative understanding of the factors which shape assembly of its diverse biota, and crucially relationships between microbiota composition and plant health. Here we investigated landscape scale rhizosphere microbial assembly processes in oilseed rape (OSR), the UK’s third most cultivated crop by area and the world's third largest source of vegetable oil, which suffers from yield decline associated with the frequency it is grown in rotations. By including 37 conventional farmers’ fields with varying OSR rotation frequencies, we present an innovative approach to identify microbial signatures characteristic of microbiomes which are beneficial and harmful to the host. Results: We show that OSR yield decline is linked to rotation frequency in real-world agricultural systems. We demonstrate fundamental differences in the environmental and agronomic drivers of protist, bacterial and fungal communities between root, rhizosphere soil and bulk soil compartments. We further discovered that the assembly of fungi, but neither bacteria nor protists, was influenced by OSR rotation frequency. However, there were individual abundant bacterial OTUs that correlated with either yield or rotation frequency. -

The Leafhopper Vectors of Phytopathogenic Viruses (Homoptera, Cicadellidae) Taxonomy, Biology, and Virus Transmission

/«' THE LEAFHOPPER VECTORS OF PHYTOPATHOGENIC VIRUSES (HOMOPTERA, CICADELLIDAE) TAXONOMY, BIOLOGY, AND VIRUS TRANSMISSION Technical Bulletin No. 1382 Agricultural Research Service UMTED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many individuals gave valuable assistance in the preparation of this work, for which I am deeply grateful. I am especially indebted to Miss Julianne Rolfe for dissecting and preparing numerous specimens for study and for recording data from the literature on the subject matter. Sincere appreciation is expressed to James P. Kramer, U.S. National Museum, Washington, D.C., for providing the bulk of material for study, for allowing access to type speci- mens, and for many helpful suggestions. I am also grateful to William J. Knight, British Museum (Natural History), London, for loan of valuable specimens, for comparing type material, and for giving much useful information regarding the taxonomy of many important species. I am also grateful to the following persons who allowed me to examine and study type specimens: René Beique, Laval Univer- sity, Ste. Foy, Quebec; George W. Byers, University of Kansas, Lawrence; Dwight M. DeLong and Paul H. Freytag, Ohio State University, Columbus; Jean L. LaiFoon, Iowa State University, Ames; and S. L. Tuxen, Universitetets Zoologiske Museum, Co- penhagen, Denmark. To the following individuals who provided additional valuable material for study, I give my sincere thanks: E. W. Anthon, Tree Fruit Experiment Station, Wenatchee, Wash.; L. M. Black, Uni- versity of Illinois, Urbana; W. E. China, British Museum (Natu- ral History), London; L. N. Chiykowski, Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa ; G. H. L. Dicker, East Mailing Research Sta- tion, Kent, England; J.